- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Mental Health and Substance Use Among Adults with Disabilities During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, February–March 2021

research-article

Mark É. Czeisler

1

,

2

,

3

,

4 ,

Amy Board , DrPH

5

,

6

,

7

,

,

JoAnn M. Thierry , PhD

5 ,

Charles A. Czeisler , PhD, MD

1

,

3

,

4 ,

Shantha M.W. Rajaratnam , PhD

1

,

2

,

3

,

4 ,

Mark E. Howard , MBBS, PhD

1

,

2

,

8 ,

Kristie E.N. Clarke , MD

5

27 August 2021

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

Adults with disabilities, a group including >25% of U.S. adults (

1

), experience higher levels of mental health and substance use conditions and lower

treatment rates than do adults without disabilities* (

2

,

3

). Survey data collected during April–September 2020 revealed elevated adverse mental

health symptoms among adults with disabilities (

4

) compared with the general adult population (

5

). Despite disproportionate risk for infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes

COVID-19, and COVID-19–associated hospitalization and mortality among some adults

with disabilities (

6

), information about mental health and substance use in this population during the

pandemic is limited. To identify factors associated with adverse mental health symptoms

and substance use among adults with disabilities, the COVID-19 Outbreak Public Evaluation

(COPE) Initiative

†

administered nonprobability–based Internet surveys to 5,256 U.S. adults during February–March

2021 (response rate = 62.1%). Among 5,119 respondents who completed a two-item disability

screener, nearly one third (1,648; 32.2%) screened as adults with disabilities. These

adults more frequently experienced symptoms of anxiety or depression (56.6% versus

28.7%, respectively), new or increased substance use (38.8% versus 17.5%), and suicidal

ideation (30.6% versus 8.3%) than did adults without disabilities. Among all adults

who had received a diagnosis of mental health or substance use conditions, adults

with disabilities more frequently (42.6% versus 35.3%; p <0.001) reported that the

pandemic made it harder for them to access related care or medication. Enhanced mental

health and substance use screening among adults with disabilities and improved access

to medical services are critical during public health emergencies such as the COVID-19

pandemic.

During February 16–March 8, 2021, among 8,475 eligible invited respondents aged ≥18

years, 5,261 (62.1%) completed nonprobability based, English-language, Internet-based

Qualtrics surveys for COPE.

§

Participants provided informed consent electronically. Quota sampling and survey weighting

were used to match U.S. Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey adult U.S.

population estimates for sex, age, and race/ethnicity to enhance the representativeness

of this nonrandom sample.

Among 5,256 respondents who answered questions for weighting variables, 5,119 (97.4%)

completed a two-question disability screener.

¶

Respondents completed clinically validated self-screening instruments for symptoms

of anxiety and depression** and reported past-month new or increased substance use

to cope with stress or emotions and serious suicidal ideation.

††

Respondents also indicated prepandemic and past-month use of seven classes

§§

of substances to cope with stress or emotions. Adults with diagnosed anxiety, depression,

posttraumatic stress disorder, or substance use disorders indicated whether their

ability to access care or medications for these conditions was easier, harder, or

unaffected because of the pandemic. Prevalence estimates for adverse mental health

symptoms and substance use were compared among adults with and without disabilities

using chi-square tests. Multivariable Poisson regression models with robust standard

error estimators were used to estimate adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs) by symptom

type among adults with and without disabilities. To calculate associations between

disability status and adverse mental health symptoms or substance use over time, aPRs

were estimated for symptoms among unique participants in previous COPE survey waves

(June, September, and December 2020). Covariates

¶¶

included sex, age group, race/ethnicity, income, U.S. Census region, urbanicity, and

parental or unpaid caregiving roles.*** McNemar’s test assessed prepandemic and past-month

substance use among adults with and without disabilities. Analyses were conducted

using Python software (version 3.7.8; Python Software Foundation) and R statistical

software (version 4.0.2; R Foundation) using the R survey package (version 3.29; R

Foundation). The Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee reviewed and approved

the study. This activity was reviewed by CDC and conducted consistent with applicable

federal law and CDC policy.

†††

Among a total of 5,119 respondents, 1,648 (32.2%) respondents reported living with

disabilities (778 [47.2%] with limiting physical, mental, or emotional conditions

only; 171 [10.4%] with health conditions requiring special equipment only; and 669

[42.4%] with both types of conditions) (Table). Overall, 64.1% of adults with disabilities

reported adverse mental health symptoms or substance use compared with 36.0% of adults

without disabilities; past-month substance use was higher among adults with disabilities

(40.6%) than among adults without disabilities (24.5%). Prevalence estimates of each

of the following were higher among adults with disabilities than among adults without

disabilities: symptoms of anxiety or depression (56.6% versus 28.7%, respectively),

new or increased substance use (38.8% versus 17.5%), and serious suicidal ideation

(30.6% versus 8.3%) (Supplementary Table, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/108999).

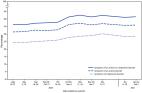

At all timepoints, aPRs for all symptom types were significantly higher among adults

with disabilities than among adults without disabilities (Figure 1). During February

16–March 8, 2021, among adults with disabilities, aPRs for symptoms of anxiety or

depression and new or increased substance use were approximately 1.5 times as high,

and the aPR for serious suicidal ideation was approximately 2.5 times as high as in

adults without disabilities. Comparing subgroups of adults with and without disabilities,

symptoms of anxiety or depression were approximately twice as prevalent among adults

with disabilities who were aged ≥50 years (aPR = 2.4; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.7–3.2),

those of non-Hispanic Asian race/ethnicity (2.4; 95% CI = 1.3–4.8), those of Hispanic

or Latino (Hispanic) ethnicity (2.1; 95% CI = 1.4–3.0), and those who were not in

parental or caregiver roles (2.1; 95% CI = 1.7–2.6). New or increased substance use

was approximately twice as prevalent among adults with disabilities in parental roles

only (2.4; 95% CI = 1.5–3.9) and among essential workers (2.3; 95% CI = 2.0–2.7).

Suicidal ideation was also more prevalent among adults with disabilities aged ≥50

years (4.0; 95% CI = 2.1–7.8), those of Hispanic ethnicity (3.4; 95% CI = 1.9–6.0),

adults in unpaid caregiving roles (3.4; 95% CI = 1.5–7.7), and essential (3.5; 95%

CI = 2.8–4.4) or nonessential (5.3; 95% CI = 2.8–10.1) workers.

TABLE

Prevalence of symptoms of anxiety or depression, substance use, and suicidal ideation

among adults with disabilities, by disability status and other characteristics — United

States, February 16–March 8, 2021

Characteristic

No. (%)

Adults with disabilities, No. (%)*

All respondents

Adults with disabilities

Symptoms of anxiety or depression†

New or increased substance use to cope§

Seriously considered suicide¶

One or more of these symptoms

Total

5,119 (100)

1,648 (32.2)

932 (56.6)

640 (38.8)

504 (30.6)

1,057 (64.1)

Disability screener**

Limited by a physical, mental, or emotional condition

778 (15.2)

778 (47.2)

417 (53.7)

218 (28.0)

148 (19.0)

465 (59.8)

Limited by a health condition that requires special equipment

171 (3.3)

171 (10.4)

104 (60.5)

88 (51.5)

65 (38.2)

123 (71.8)

Both of above

699 (13.7)

669 (42.4)

411 (58.8)

334 (47.8)

291 (41.5)

469 (67.1)

Neither of above

3,471 (67.8)

0 (—)

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

Sex

††

Female

2,499 (48.8)

789 (47.9)

445 (56.5)

260 (32.9)

178 (22.6)

501 (63.5)

Male

2,583 (50.5)

838 (50.8)

469 (55.9)

369 (44.0)

314 (37.4)

537 (64.1)

Age group, yrs

18–29

938 (18.3)

314 (19.0)

250 (79.8)

185 (59.1)

136 (43.3)

276 (87.8)

30–39

967 (18.9)

325 (19.7)

259 (79.8)

198 (60.9)

166 (51.1)

281 (86.6)

40–49

818 (16.0)

253 (15.4)

180 (70.9)

137 (54.0)

125 (49.5)

202 (79.6)

50–59

972 (19.0)

309 (18.8)

132 (42.6)

80 (25.9)

54 (17.5)

158 (51.2)

60–69

790 (15.4)

235 (14.2)

59 (25.2)

21 (8.9)

4 (1.8)

72 (30.7)

≥70

634 (12.4)

213 (12.9)

52 (24.7)

19 (8.8)

19 (8.8)

68 (31.9)

Race/Ethnicity

White, non-Hispanic

3,103 (60.6)

975 (59.2)

522 (53.6)

327 (33.5)

266 (27.3)

585 (60.0)

Black, non-Hispanic

638 (12.5)

181 (11.0)

99 (54.6)

68 (37.9)

35 (19.3)

110 (60.9)

Asian, non-Hispanic

289 (5.6)

65 (3.9)

39 (61.1)

18 (27.8)

14 (21.0)

47 (72.1)

Multiple/other race, non-Hispanic§§

188 (3.7)

70 (4.3)

32 (45.2)

16 (23.3)

13 (18.3)

32 (45.8)

Hispanic or Latino, any race

902 (17.6)

357 (21.7)

240 (67.2)

210 (58.8)

177 (49.5)

283 (79.3)

2020 Household income, USD

¶¶

<25,000

1,182 (23.1)

544 (33.0)

286 (52.6)

151 (27.8)

107 (19.7)

327 (60.0)

25,000–49,999

1,203 (23.5)

355 (21.5)

179 (50.4)

110 (30.9)

82 (23.2)

202 (56.9)

50,000–99,999

1,306 (25.5)

350 (21.2)

191 (54.6)

134 (38.2)

103 (29.5)

218 (62.1)

≥100,000

1,204 (23.5)

341 (20.7)

253 (74.1)

232 (68.1)

205 (60.1)

286 (83.8)

Education

High school diploma or less

1,379 (26.9)

485 (29.4)

264 (54.4)

155 (31.8)

135 (27.9)

309 (63.7)

College or some college

2,876 (56.2)

865 (52.5)

463 (53.5)

312 (36.0)

213 (24.6)

520 (60.1)

After bachelor's degree

865 (16.9)

298 (18.1)

206 (69.0)

174 (58.2)

156 (52.3)

228 (76.4)

Employment status

Employed (essential employee)

1,797 (35.1)

605 (36.7)

475 (78.6)

448 (74.2)

371 (61.4)

542 (89.6)

Employed (nonessential employee)

941 (18.4)

151 (9.1)

87 (57.9)

53 (35.2)

38 (25.4)

103 (68.3)

Unemployed

936 (18.3)

349 (21.2)

190 (54.5)

77 (22.2)

55 (15.9)

207 (59.3)

Retired

1,263 (24.7)

493 (29.9)

142 (28.8)

45 (9.1)

24 (4.8)

167 (33.8)

Student

182 (3.6)

51 (3.1)

38 (73.7)

16 (31.9)

15 (29.8)

38 (74.5)

Parental role and unpaid caregiving status***

Neither parent nor caregiver

2,882 (56.3)

741 (44.9)

294 (39.7)

90 (12.2)

70 (9.4)

323 (43.6)

Parent only

611 (11.9)

189 (11.5)

97 (51.3)

48 (25.1)

21 (11.3)

110 (58.0)

Caregiver role of adults only

426 (8.3)

117 (7.1)

57 (48.6)

39 (33.1)

24 (20.9)

71 (60.5)

Parental and caregiver roles

1,201 (23.5)

602 (36.5)

485 (80.5)

463 (77.0)

389 (64.6)

553 (92.0)

U.S. Census region

†††

Northeast

899 (17.6)

267 (16.2)

177 (66.0)

119 (44.7)

109 (40.6)

188 (70.5)

Midwest

1,069 (20.9)

349 (21.1)

208 (59.8)

126 (36.0)

94 (27.1)

222 (63.6)

South

2,074 (40.5)

700 (42.5)

367 (52.4)

262 (37.4)

195 (27.9)

442 (63.1)

West

1,077 (21.0)

333 (20.2)

180 (54.2)

133 (40.1)

106 (31.8)

205 (61.7)

Urbanicity (n = 5,091)§§§

Urban

4,241 (83.3)

1,313 (79.6)

761 (58.0)

544 (41.4)

440 (33.5)

866 (66.0)

Rural

850 (16.7)

322 (19.5)

158 (49.1)

87 (27.1)

56 (17.4)

178 (55.2)

Abbreviations: N/A = not applicable; USD = U.S. dollars.

* Weighted rounded counts and percentages might not sum to expected values.

† Symptoms of anxiety and depression were assessed via the four-item Patient Health

Questionnaire (PHQ-4). Respondents who scored ≥3 out of 6 on the Generalized Anxiety

Disorder (GAD-2) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) subscales were considered

symptomatic for these respective conditions.

§ New or increased substance use was assessed by using the question, “Have you started

or increased using substances to help you cope with stress or emotions during the

COVID-19 pandemic? Substance use includes alcohol, legal or illegal drugs, or prescription

drug use in any way not directed by a doctor.”

¶ Suicidal ideation was assessed by using an item from the National Survey on Drug

Use and Health (https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/homepage.cfm) adapted to refer to

the previous 30 days, “At any time in the past 30 days, did you seriously think about

trying to kill yourself?”

** Adults who had a disability were defined as such based on a qualifying response

to either one of two questions: “Are you limited in any way in any activities because

of physical, mental, or emotional condition?” and “Do you have any health conditions

that require you to use special equipment, such as a cane, wheelchair, special bed,

or special telephone?” Respondents who completed only one of the two disability screening

questions (limited by a physical, mental, or emotional condition: 17); limited by

a health condition that requires special equipment: 12) were classified as living

with only that disability. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdf-ques/2015-brfss-questionnaire-12-29-14.pdf

†† Gender responses of “Transgender” (22; 0.4%) and “None of these” (15; 0.3%) are

not shown because of small counts.

§§ The non-Hispanic, multiple/other race or multiple races category includes respondents

who identified as not Hispanic and as more than one race or as American Indian or

Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or any other race.

¶¶ Household income responses of “Prefer not to say” (225) are not shown because of

an inability to sufficiently characterize these responses.

*** Adults who were in parental or unpaid caregiving roles were self-identified. For

this analysis, the definition of unpaid caregivers of adults was having provided unpaid

care to a relative or friend ≥18 years to help them take care of themselves at any

time during the 3 months before the survey. The definition of someone in a parental

role was having provided unpaid care to a relative or friend <18 years. Respondents

answered these questions separately. During analysis, all respondents were categorized

as being in a parental role only, caregivers of adults only, having both parental

and caregiving roles, or having neither parental nor caregiving roles. Adults in parenting

roles might not have been natural or legal parents of children in their care.

†††

https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf

§§§ Invalid postcodes were provided by 28 respondents, for whom urbanicity was not

categorized. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/definition/datafiles.html

FIGURE 1

Adjusted prevalence ratios* and 95% confidence intervals

†

for ≥1 symptoms of adverse mental health or substance use (A), symptoms of anxiety

or depression (B), new or increased substance use (C), and suicidal ideation (D) among

adults with disabilities, compared with adults without disabilities (referent group)

§

— United States, February 16–March 8, 2021¶

Abbreviations: aPR = adjusted prevalence ratio; CI = confidence interval.

* With 95% CIs indicated by error bars. Multivariable Poisson regression models included

sex, age group in years, race/ethnicity, income, U.S. Census region, urbanicity, and

parental or unpaid caregiving roles (parental roles were not assessed in June 2020;

only unpaid caregiving roles were considered for this variable in the June 2020 models).

Separate, additional models were run to estimate aPRs for the following employment

statuses: essential worker, nonessential worker, and unemployed. Estimates were not

made for retired or student employment statuses because of collinearity between these

employment statuses and age.

† For panels A, B, and C, the y-axis range for aPR estimates is 0–5, which contains

all aPRs and 95% CIs for these panels with maximal view of differences in model estimates.

For panel D, given the relative rarity of suicidal ideation among some demographic

subgroups that results in wide CIs for aPR estimates, the y-axis range is 0–10.

§ Within each subgroup, adults without disabilities are the reference group used to

estimate aPRs for outcomes among adults with disabilities.

¶ Estimated aPRs are during February 16–March 8, 2021, except for the “over time”

estimates, which also include estimates based on data collected during June 24–30,

2020, August 28–September 6, 2020, and December 6–27, 2020.

Figure consists of four bar graphs that show adjusted prevalence ratios and 95% confidence

intervals for mental health and substance use among adults with disabilities versus

adults without disabilities, United States, February 16 through March 8, 2021.

The prevalence of substance use to cope with stress or emotions among adults with

disabilities was higher than that among adults without disabilities, both prepandemic

(39.7% versus 25.3%, respectively) and in the past month (40.6% versus 24.5%; both

p<0.001) (Figure 2). Among adults with disabilities, the past-month prevalence of

methamphetamine use (8.4%), nonopioid prescription drug misuse (4.9%), and polysubstance

use (16.9%) was approximately twice as high, and the prevalence of cocaine use (6.4%)

and prescription or illicit opioid use (9.1%) were nearly three times as high compared

with those among adults without disabilities (methamphetamine use 3.4%; nonopioid

prescription drug misuse 2.0%; polysubstance use 7.9%; cocaine use 2.2%; prescription

or illicit opioid use 3.2%). Past-month methamphetamine use prevalence increased significantly

compared with prepandemic use prevalence among all respondents (with disabilities,

45.6% increase, p<0.001; without disabilities, 40.6% increase, p = 0.003). Among respondents

who reported a diagnosed mental health or substance use condition, a higher percentage

of adults with (versus without) disabilities reported that accessing care or medication

was harder because of the COVID-19 pandemic (42.6% versus 35.3%, respectively, p<0.001).

FIGURE 2

Prevalence of prepandemic and past-month substance use to cope with stress or emotions

among adults, by disability status and type of substance — United States, February

16–March 8, 2021*

,

†

,

§

* Overall, prepandemic and past-month use of any of these substances were reported

by 39.7% and 40.6%, respectively, of adults with disabilities, and by 25.3% and 24.5%,

respectively, of adults without disabilities.

† All differences between adults with disabilities and adults without disabilities

were significant (chi-square p-value <0.05).

§ Circles for use of marijuana (among adults with disabilities), use of prescription

drugs (among adults without disabilities), and polysubstance use (among adults with

disabilities) might appear overlapping because of very small changes in reported prevalence

(<1% in all cases).

Figure shows the prevalence of prepandemic and past-month substance use to cope with

stress or emotions among adults by disability and substance type, United States, February

16–March 8, 2021.

Discussion

Nearly two thirds of surveyed adults with disabilities (who represented approximately

32% of the sample) reported adverse mental health symptoms or substance use in early

2021, compared with approximately one third of adults without disabilities. Serious

suicidal ideation was approximately 2.5 times as high among adults with disabilities,

and methamphetamine use, opioid use, nonopioid prescription drug misuse, and polysubstance

use were at least twice as prevalent among adults with disabilities. These findings

suggest value in enhanced mental health screening among adults with disabilities and

in ensuring accessibility of routine and crisis services, particularly given that

many adults reported that the COVID-19 pandemic had reduced mental health and substance

use care or medication accessibility. Mental health disparities among adults with

disabilities were observed across demographic groups, highlighting the importance

of ensuring access to disaster distress

§§§

and suicide prevention

¶¶¶

resources in this population. Important strategies to prevent persons from becoming

suicidal include strengthening economic supports, promoting connectedness, and teaching

coping skills.**** Health care providers could incorporate trauma-informed care, because

adults with disabilities might have encountered stigma and trauma in previous health

care interactions. Adults with disabilities more frequently reported prepandemic and

past-month substance use to cope with stress or emotions compared with adults without

disabilities. The substance with the largest increase in use was methamphetamine,

which is particularly concerning given the increase in amphetamine overdoses

††††

(

7

). Drug overdose deaths rose in 2020, driven by synthetic opioids.

§§§§

Consistent with previous research, adults with disabilities disproportionately reported

opioid use and nonopioid prescription drug misuse (

8

), highlighting the importance of educating patients and ensuring clinician access

to prescription drug monitoring programs.

¶¶¶¶

Nearly one in ten adults with disabilities reported past-month opioid use, and opioid

use among adults without disabilities increased. Policies that reduce barriers to

evidence-based treatment, including recently updated buprenorphine practice guidelines,*****

might improve access.

The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, self-reported

mental health and substance use might be subject to social desirability biases and

stigma, which could lead to underreporting. Second, because the surveys were English-language

only and data were obtained using nonprobability–based sampling, despite quota sampling

and survey weighting, the findings from this nonrandom sample might not be generalizable.

However, the proportion and demographics of surveyed adults with disabilities were

similar to those of recent samples from other sources with the same or similar screening

questions (

1

,

2

,

4

), and prevalence estimates of symptoms of anxiety and depression were largely consistent

with those from other sources for the U.S. adult population (

9

) and adults with disabilities (

4

) including the U.S. Census Bureau’s probability-based Household Pulse Survey (64.3%

among adults with disabilities compared with 27.4% among adults without disabilities

in April 2021).

†††††

Third, the respondents with disabilities might not be representative of all adults

with disabilities, some of whom might lack access to hardware or assistive technologies

required to independently complete the survey. Finally, adverse mental health symptoms

might, in some cases, represent respondents’ disabling mental health conditions, which

could confound associations with other comorbid disabling conditions (e.g., physical,

cognitive, sensory); however, sensitivity analyses excluding adults with disabilities

who had mental health or substance use diagnoses yielded consistent findings.

Adults with disabilities have been disproportionately affected by adverse mental health

symptoms and substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting the importance

of improved access to treatment for this population. Clinicians might consider screening

all patients for mental health and substance use conditions during and after the pandemic.

§§§§§

Behavioral health care providers might also consider facility, policy, and procedural

pathway analyses to ensure accessibility for clients with physical, sensory, or cognitive

disabilities.¶¶¶¶¶ Strategies designed to increase access to care and medication during

public health emergencies, such as telehealth, might consider telemedicine platform

and system accessibility for adults with disabilities (

10

); further research to identify and address health disparities among adults with disabilities

could help guide additional evidence-based strategies.

Summary

What is already known about this topic?

Adults with disabilities experience higher levels of mental health conditions and

substance use than do adults without disabilities.

What is added by this report?

During February–March 2021, 64.1% of surveyed U.S. adults with disabilities reported

adverse mental health symptoms or substance use; past-month substance use was higher

than that among adults without disabilities (40.6% versus 24.5%, respectively). Among

adults with a diagnosis of mental health or substance use conditions, adults with

disabilities more frequently (43% versus 35%) reported pandemic-related difficulty

accessing related care and medications.

What are the implications for public health practice?

During public health emergencies, including the COVID-19 pandemic, enhanced mental

health and substance use screening among adults with disabilities and improved access

to related health care services are critical.

Related collections

Most cited references9

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Prevalence of Disabilities and Health Care Access by Disability Status and Type Among Adults — United States, 2016

Catherine A Okoro, NaTasha D. Hollis, Alissa Cyrus … (2018)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found