- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Ambient fine particulate matter in Latin American cities: Levels, population exposure, and associated urban factors

Read this article at

Abstract

Background

Exposure to particulate matter (PM 2.5) is a major risk factor for morbidity and mortality. Yet few studies have examined patterns of population exposure and investigated the predictors of PM 2.5 across the rapidly growing cities in lower- and middle-income countries.

Objectives

Characterize PM 2.5 levels, describe patterns of population exposure, and investigate urban factors as predictors of PM 2.5 levels.

Methods

We used data from the Salud Urbana en America Latina/Urban Health in Latin America (SALURBAL) study, a multi-country assessment of the determinants of urban health in Latin America, to characterize PM 2.5 levels in 366 cities comprising over 100,000 residents using satellite-derived estimates. Factors related to urban form and transportation were explored.

Results

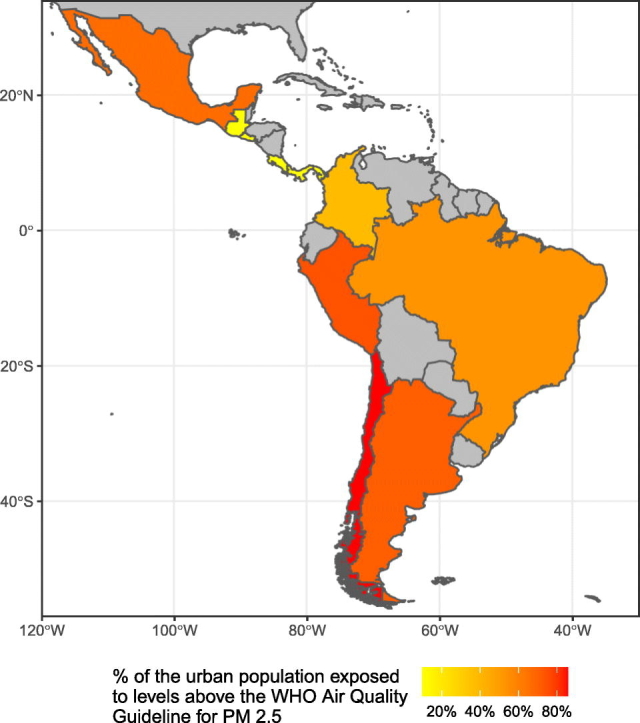

We found that about 172 million or 58% of the population studied lived in areas with air pollution levels above the defined WHO-AQG of 10 μg/m 3 annual average. We also found that larger cities, cities with higher GDP, higher motorization rate and higher congestion tended to have higher PM 2.5. In contrast cities with higher population density had lower levels of PM 2.5. In addition, at the sub-city level, higher intersection density was associated with higher PM 2.5 and more green space was associated with lower PM 2.5. When all exposures were examined adjusted for each other, higher city per capita GDP and higher sub-city intersection density remained associated with higher PM 2.5 levels, while higher city population density remained associated with lower levels. The presence of mass transit was also associated with lower PM 2.5 after adjustment. The motorization rate also remained associated with PM 2.5 and its inclusion attenuated the effect of population density.

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Cities in Latin America with higher GDP, motorization rate, and congestion have higher PM 2.5.

-

•

Cities in Latin America with higher population density and green space have lower levels of PM 2.5.

-

•

Intersection density and mass transit infrastructure also impact pollution levels.

-

•

Urban planning and transportation policies may have a major impact on air pollution.

Related collections

Most cited references42

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Fine-particulate air pollution and life expectancy in the United States.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found