- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Equitability of Depression Screening After Implementation of General Adult Screening in Primary Care

Read this article at

Key Points

Question

Is implementation of routine depression screening in primary care associated with improved screening rates for groups at risk for undertreatment of depression?

Findings

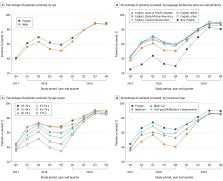

In this cohort study of 52 944 adult patients in primary care practices in a California health system, depression screening rates increased from 40.5% in 2017 to 88.8% in 2019 after implementation of a general screening policy. Initial statistically significant screening disparities among older patients, Black/African American and other English-speaking patients, and patients with language barriers disappeared by 2019, although disparities for men did not.

Abstract

Importance

Depression is a debilitating and costly medical condition that is often undertreated. Men, racial and ethnic minority individuals, older adults, and those with language barriers are at increased risk for undertreatment of depression. Disparities in screening may contribute to undertreatment.

Objective

To examine depression screening rates among populations at risk for undertreatment of depression during and after rollout of general screening.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study from September 1, 2017, to December 31, 2019, of electronic health record data from 52 944 adult patients at 6 University of California, San Francisco, primary care facilities assessed depression screening rates after implementation of a general screening policy. Patients were excluded if they had a baseline diagnosis of depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or dementia.

Exposures

Screening year, including rollout (September 1, 2017, to December 31, 2017) and each subsequent calendar year (January 1 to December 31, 2018, and January 1 to December 31, 2019).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Rates of depression screening performed by medical assistants using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2. Data collected included age, sex, race and ethnicity, and language preference (English vs non-English); to compare English and non-English language preference groups and also assess depression screening by race and ethnicity within the English-speaking group, a single language-race-ethnicity variable with non–English language preference and English language preference categories was created. In multivariable analyses, the likelihood of being screened was evaluated using annual logistic regression models for 2018 and 2019, examining sex, age, language-race-ethnicity, and comorbidities, with adjustment for primary care site.

Results

There were 52 944 unique, eligible patients with 1 or more visits in one of the 6 primary care practices during the entire study period (59% female; mean [SD] age, 48.9 [17.6] years; 178 [0.3%] American Indian/Alaska Native, 13 241 [25.0%] English-speaking Asian, 3588 [6.8%] English-speaking Black/African American, 4744 [9.0%] English-speaking Latino/Latina/Latinx, 760 [1.4%] Pacific Islander, 22 689 [42.9%] English-speaking White, 4857 [9.0%] English-speaking other [including individuals who indicated race and ethnicity as other and individuals for whom race and ethnicity data were missing or unknown], and 2887 [5.5%] with language barriers [non–English language preference]). Depression screening increased from 40.5% at rollout (2017) to 88.8% (2019). In 2018, the likelihood of being screened decreased with increasing age (adusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.89 [95% CI, 0.82-0.98] for ages 45-54 and aOR, 0.75 [95% CI, 0.65-0.85] for ages 75 and older compared with ages 18-30); and, except for Spanish-speaking patients, patients with limited English proficiency were less likely to be screened for depression than English-speaking White patients (Chinese language preference: aOR, 0.59 [95% CI, 0.51-0.67]; other non–English language preference: aOR, 0.55 [95% CI, 0.47-0.64]). By 2019, depression screening had increased dramatically for all at-risk groups, and for most, disparities had disappeared; the odds of screening were only still significantly lower for men compared with women (aOR, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.81 to 0.93]).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study in a large academic health system, full implementation of depression screening was associated with a substantial increase in screening rates among groups at risk for undertreatment of depression. In addition, depression screening disparities narrowed over time for most groups, suggesting that routine depression screening in primary care may reduce screening disparities and improve recognition and appropriate treatment of depression for all patients.

Abstract

This cohort study assesses rates of depression screening among groups at risk for undertreatment of depression after initiation of routine primary care screening for adults in a large health system.

Related collections

Most cited references71

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found