Introduction

George Horsfield was the first Chief Curator/Inspector of the Transjordan Department of Antiquities from 1924/6–1936. With his future wife Agnes Conway and two other scholars he conducted the first ‘scientific’ excavations at Petra (e. g. Horsfield & Horsfield 1938a, 1938b, 1942; see also Parr 1990: 8). Finding George Horsfield in the archives has been a fascinating challenge. Colleagues and acquaintances alike recalled his temperamental nature1, which shrouds both the elucidation of his personality and his work in Transjordan with a whiff of mystery. In letters to Conway he referred to himself as a ‘nobody’ (e. g. Horsfield 1931i), but his work in Transjordan, then a British Protectorate, now the Kingdom of Jordan, leaves a significant legacy – not least here at the Institute where part of the Horsfields’ archive is kept.

I have explored early efforts and breakthroughs in my work on Horsfield in a short description of Horsfield’s entrance into archaeology (Thornton 2009). In my doctoral thesis I examined his professional life and personal network in the context of wider political developments in the British Mandate system (Thornton 2011b); and more recently I have chronicled his contributions to the archaeology and tourism of Transjordan (Thornton 2012). Horsfield contributed to shaping the archaeological heritage of Transjordan, and consequently the impact of his work continues to affect the tourists and the archaeological teams that travel to Jordan today.

One of the most important factors in the enduring appeal of archaeology is archaeologists themselves. In my current postdoctoral project, I will be exploring the British archaeological identity through the production of popular archaeological publications. This research has evolved from my doctoral research (Thornton 2011b), which used the archives of five British archaeologists - George Horsfield, Agnes Conway Horsfield, John Garstang, John Crowfoot and Molly Crowfoot - to analyse how their personal experiences reflected wider issues in the social history of archaeology.

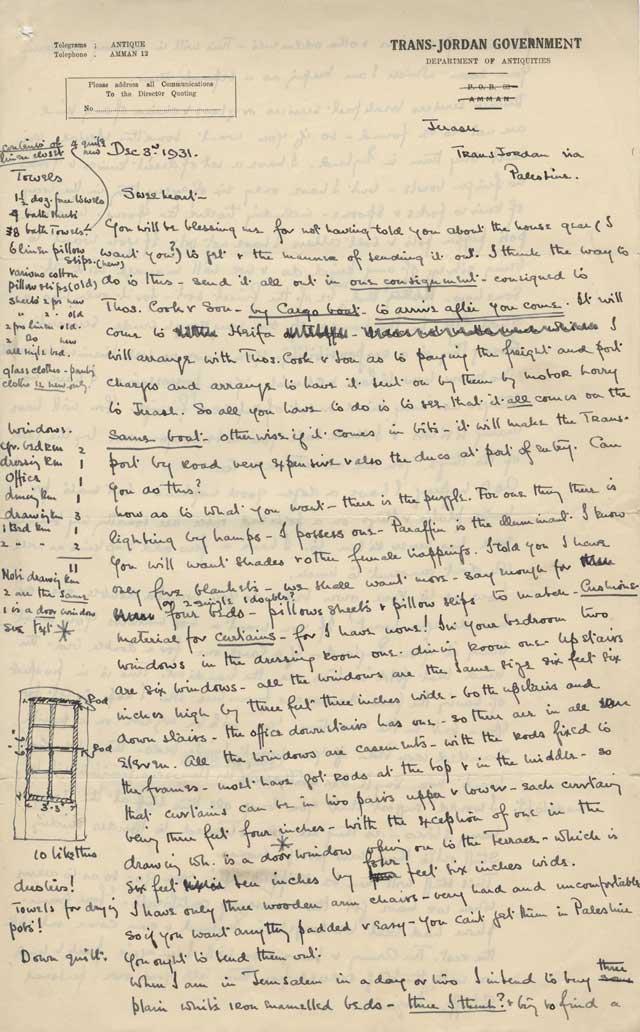

So, what makes up a British archaeological identity? I started to address this question in a recent article on archaeologists Gerald Lankester Harding and Margaret Murray (Thornton 2014). Like other archaeologists of the time, George Horsfield’s journey to archaeology did not follow a straight path. He moved countries and continents multiple times during his life, taking advantage of opportunities for professional development and change, and expanding his experiences. One of the key sources for examining Horsfield’s life and work within the political and social environment of British Mandate Transjordan is a collection of letters from George Horsfield to Agnes Conway, whom he married in January 1932 (Fig. 1). This correspondence is a small part of the Horsfields’ archaeological archive, donated by George Horsfield to the Institute of Archaeology in 1951 (see Thornton 2006, Thornton & Perry 2011). Dating from autumn 1931 to summer 1932, the correspondence began as Horsfield undertook the ten-day voyage back to the Middle East after proposing marriage to Conway. The letters continued in the months leading up to, and after, their marriage.

The first page of a letter from Horsfield to Conway, written on Transjordan Department of Antiquities stationery. (Copyright UCL Institute of Archaeology).

Horsfield’s pre-wedding letters are those of an impatient, passion-filled lover. At 49, he considered himself an old man, but his letters have the longing desperation of a ‘boy of twenty!’ as he put it (Horsfield n. d. 1931a). Although they are not of much archaeological significance, revealing only glimpses of the day to day work that Horsfield undertook as Chief Curator/Inspector, taken together with other sources the correspondence yields illuminating insights into the social history of British archaeology abroad, official life in Mandate Transjordan, and George Horsfield’s personal and professional history.

The Architect

George Wilberforce Horsfield was the son of a leather manufacturer, Richard Marshall Horsfield, whose Meanwood Road Leather Works in Leeds produced a range of leather goods (Leeds Mercury 1893). He was admitted as a student to Leeds Grammar School in 1895, and in 1901 moved to London to undertake a pupillage (an architect’s apprenticeship) in Gothic Revival architect George Frederick Bodley’s firm (Thornton 2009; 2011b). Horsfield felt himself an outsider – the black sheep of a family of respectable middle class trade, the only one with an interest in art and ancient history, fostered under his mother’s care (Horsfield c. 1926–1936; Horsfield 1931i, k). His correspondence at the Institute of Archaeology only reveals hints of his life in London – a brief mention of his friendship with a nameless ‘starving artist’ (Horsfield 1931k) suggests his acquaintance with the city’s bohemian elements (see Brooker 2004; Nicholson 2003). He developed a specialty in church interiors and interior decoration (see Conway 1932; Kirkbride 1956: 58; Horsfield 1931l). This is reflected in the fact that he later incorporated a small chapel into the house he occupied in Jerash, Transjordan (Fig. 2).

Horsfield expanded his professional experience with a move to America, becoming head designer and draughtsman in the architectural practice of Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, a noted Gothic Revival architect and partner in the firm Cram, Goodhue and Ferguson (Horsfield c. 1926–1936; Thornton 2009, 2011b). Goodhue was known for his bohemian, romantic, thoroughly artistic approach to Gothic architecture, and fostered this sensibility in his New York City office – illustrated in colourful splendour every year at his annual Twelfth Night party (see Anderson n. d.: Ch. 3; Pencil Points 1922; Schuyler 1911: 8–11; Thornton 2009, 2011b; Wyllie 2007). Horsfield later stated that his time in New York offered him more opportunities for ‘self-expression’ than any previous experiences (Horsfield c. 1926–1936). It is clear that he became part of the New York architectural scene in both a practical and intellectual sense. Signing himself ‘Wilberforce Horsfield’ he contributed two front cover illustrations and an article to Architectural Record, a monthly architecture journal published in New York City with a national circulation that is still issued today. In its early 20th centrury form Architectural Record combined pieces on the culture and history of architecture with descriptions and analyses of projected, on-going or recently completed building projects (Lichtenstein 1990: 17–35; Thornton 2011b). Horsfield’s covers and article focus on Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral, then being constructed to Giles Gilbert Scott’s design.

His final words on Gilbert Scott’s creation seem to sum up his philosophy on architecture:

‘As to the style, it is difficult to speak – Gothic in the large sense of the word, but not one to be confounded with any particular one of the tabulated styles. It shows familiarity with and study of ancient forms, but it is no diatessaron of undigested parts collected at haphazard fancy and flung together in the mode of the Gothic Revival […]. It is modern of the twentieth century, of today, thoroughly digested, and has been tied to no style – an example of living modern architecture as applied to a religious problem […] Modern method facing and solving an ancient problem’ (Horsfield 1912: 42).

Considering Horsfield’s later career included clearing and beginning renovations on ancient Roman remains in Transjordan, these words seem to provide something of a precedent for his later interests. He helped to bring ancient remains into modern use for tourism.

In 1912 Horsfield and a friend established their own office in New York City. It was a brief foray into solo-practice – Horsfield’s friend died suddenly only weeks before Britain declared war on Germany in August 1914. Horsfield returned to England in September 1914 and enlisted (Horsfield c. 1926–1936; Thornton 2009, 2011b). The war years were transformative for Horsfield. Aged 32, he became a private in the Royal Naval Brigade, seeing action in the first campaign at Gallipoli, after which he was commissioned as an officer in the 7th West Yorkshire regiment and sent to the Western Front. He wrote a few letters to his former employer Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue during this period. These give a flavour of his war from which one can surmise the horrors of the trenches. He was on the Somme in late summer 1916 and then elsewhere on the Western Front, enduring monotony, mud and death; by 1917 this traumatic experience had taken a toll on his health. Hospitalised with trench fever, he was sent back to England. His next post was to India where eventually he resumed practising architecture once more (Horsfield 1917; Horsfield c. 1926–1936; Thornton 2009, 2011b).

His own account of his movements for the immediate post-war period is vague; after being demobilised from army service in India he spent over a year travelling in Europe (Horsfield c. 1926–1936; Thornton 2009, 2011b). By early 1923 he had been admitted as a student at the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. This is when he became fully immersed in archaeological work (Horsfield c. 1926–1936; Thornton 2009, 2011b). Within two years he was undertaking initial clearances at Jerash, the ancient Roman city of Gerasa, in preparation for making it accessible to tourists – part of a programme to increase ‘heritage’ tourism to Transjordan and Palestine (see Horsfield 1926; Thornton 2012). His correspondence to Agnes Conway gives an interesting insight into the first years of his work in Transjordan (1924–1926), during which it appears he travelled frequently between there and Palestine:

‘I never really got over my first two years of Hell here – it was hell. I had to work like a slave + be a slave driver at the same time – incidentally learning my job for truthfully I knew nothing but theories when I went to Jerash – the lack of language was nothing – but the lack of experience was awful – it grew like a tree + I grew more and more feeble with worry + starvation – Do you remember how I used to sleep on the smallest provocation? It was sheer tiredness – brought on by the incessant labour and travelling during my first few years here – during a large part of which there was hardly anything to eat’ (Horsfield n. d. 1931b).

Despite these difficulties, in Transjordan Horsfield made his mark. In clearing the Southern theatre in Jerash, Horsfield (presumably with a team of locally employed workmen) uncovered the theatre’s podium, intact.2 This discovery made him a ‘Personality of the Week’ in the 1st August 1925 issue of the Illustrated London News (ILN 1925a, b, c). A photograph in the Horsfield archive at the Institute was used for the publication (Fig. 3). The following year a purported ‘Head of Christ’ - a sculpted head of Roman date discovered during Horsfield’s continuing clearance operations at Jerash - made it to the front page of the Illustrated London News (ILN 1926a, Thornton 2009). The article accompanying the cover photograph highlighted Horsfield as one of the emerging stars of archaeology in Mandate Palestine and Transjordan (ILN 1926b).

Horsfield’s ‘Personality of the Week’ photograph, which was taken in Jerash in 1924. It was slightly adapted for publication in the Illustrated London News. (Copyright UCL Institute of Archaeology). [First published in Thornton 2009].

The Official

When he assumed an official position in the Transjordan Department of Antiquities as Chief Curator/Inspector3 at a salary of £800 per annum (Horsfield 1931h), Horsfield became a part of the imperial system – the disparate yet connected band of administrators, officials and staff who worked within Britain’s interests overseas. More specifically for archaeology, he joined the small group of archaeologists with professional posts – roughly equivalent to Office of Works Ancient Monuments inspectors in England4, and parallel to the British inspectors for the Antiquities Service in Egypt and the Antiquities Department in Palestine (Thornton 2011b).

Anthony Kirk-Greene (1999: 93) has written about the impracticality of comparing imperial experiences, but the British Egyptian Antiquities Service inspectors provide the most obvious precedent for Horsfield’s experience.5 In 1899 Gaston Maspero, French Director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, appointed two British inspectors, Howard Carter and James Edward Quibell. They were the first Britons to obtain such posts in Egypt’s French-controlled Antiquities Service, and they joined French and Egyptian inspectors to carry out the Service’s work (see Reid 2002: 195–196; Thornton 2011b). Both men lived in Egypt. In 1905, on Carter’s resignation, Arthur Weigall was appointed. The same year, a third British inspector, Campbell Cowan Edgar, joined the Inspectorate (Hankey 2001: 46; Reeves and Taylor 1992: 56).

Biographies of Carter (Reeves and Taylor 1992: 56–84) and Weigall (Hankey 2001) describe the life of an antiquities inspector – living ‘in country’ with limited available leave to return to England or the Continent, constant travel between sites, and navigating relationships with local communities, other archaeologists and officialdom.6 Professional posts in archaeology were few and far between, but more emerged as antiquities departments were firmly established after the First World War in Sudan, Palestine, Transjordan and Iraq (Thornton 2011b).7 Biographies of antiquities inspectors show both the appeal and the restrictions of inspectorate roles. For the individual inspector, an annual salary and a house were two of the most important personal perks, but the professional demands – being the man on the ground for disputes, navigating official expectations and policies, and implementing management strategies, could take away from intellectual pursuits (see Hankey 2001: 52–53).8

Approaches to antiquities inspection duties varied between individual inspectors. Reeves & Taylor demonstrate that as an inspector Howard Carter considered that part of his role was to secure funding for particular excavation or preservation projects that he would undertake (1992: 70–71). However, personal research was not always at the forefront during the course of an inspectorate – Arthur Weigall made a conscious decision to give up his own research in favour of a more administrative/managerial role (Hankey 2001: 52–53). Horsfield’s approach paralleled Carter’s: in 1929 with the prospect of undertaking an excavation at Petra funded by the British philanthropist Henry Mond (Lord Melchett) in the offing, Horsfield facilitated and managed the official logistics of the excavation (Thornton 2011b). Maintaining a good relationship with Melchett was important. In 1931 as Melchett prepared to visit Transjordan, Horsfield wrote to his fiancée: ‘Keep in touch with Melchetts movements + so that we can be at hand to lead him about when he does come’ (Horsfield 1931q, t).

For some inspectors, the job could mean having a house near a city with a significant British official community, associated British institutions and clubs, and the social pressures that went with them. Hankey records that these factors shaped Weigall’s experience as the Southern region inspector based in Luxor, Egypt (2001: 60). Horsfield’s experience was somewhat similar. Amman was the social centre of British officialdom in Transjordan, and where the British Residency was located. Horsfield told his fiancée that ‘Col. Cox [British Resident] was very charming about you + is glad to think you are joining our little community […]’ (Horsfield 1931l). However, his correspondence also reveals his wish for self-imposed exile from official life. Despite the positive tone in the passage above Horsfield was not overly fond of spending time in Transjordan’s administrative headquarters and he often expressed his frustration with the political climate. On an earlier occasion, a letter to Conway contained his patronising criticism of Amman: ‘I think you will be amused by the politics out here – the mass of silly intrigues of an Arab Government – we fortunately won’t get much of them except when we are in this horrid capital’ (Horsfield 1931e).

Horsfield’s house was in Jerash, less than two hours’ drive north west of Amman, but reachable only by car. He described it as ‘small’, ‘a miserable house in a ruin’ (Horsfield 1931f, h). The ruin was the Roman Gerasa, which in the 1930s was surrounded by Jerash village (Fig. 4), in which lived many Circassian families - descendents of 19th century immigrants from the Caucasus (Luke and Keith Roach 1930: 403; Thornton 2012).

A detail from a contact print in the Horsfield archive showing a view through the Propylea of Artemis with Jerash village beyond. (Copyright UCL Institute of Archaeology).

The ruins of Gerasa were under active investigation throughout this period, including British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem excavations, and Yale University excavations headed by Clarence Fisher of the American Schools of Oriental Research (see Fisher & McCown 1929/1930). ‘Antiquity House’ (Fig. 5), as Horsfield’s residence was called, was six rooms with outbuildings, which he proposed to alter to accommodate the needs and wants of his bride. It was inside ancient Gerasa, between the Propylea of Artemis and the Temple of Artemis.9 Horsfield wrote teasingly to his fiancée:

‘Did you ever watch an excavation as you lay in bed? Such is my fortune here – for the learned Dr Fisher is delving for walls inside the upper colonnade of the Temple of Artemis. Do you realise that your future abode is in the precinct of Diana the huntress goddess? It is’ (Horsfield n. d. 1931b).

He described the house in minute detail in his letters to Conway. Images in the Horsfield archive give a flavour of its (eventual) comforts (Figs 6 and 7).

Plan of the ground floor of ‘Antiquity House’, the Horsfields’ residence in Jerash, showing Horsfield’s proposed adjustments to the layout in late 1931. (Copyright UCL Institute of Archaeology).

George Horsfield sitting in ‘Antiquity House’, surrounded by books. (Copyright UCL Institute of Archaeology).

The context in which much of Horsfield’s day to day life took place was that of a small village, with all the associated intrigues, quarrels and family feuds that arose within the community. However, Horsfield was also a representative of the British and Transjordan governments and his house was essentially a government outpost.10 He played host to the government officials who came to visit; as he put it: ‘[…] I keep an open house in a way here – we always have people dropping in for a night’ (Horsfield 1931i). Visitors included everyone from the (British) High Commissioner of Transjordan and Palestine to travellers caught en route in bad weather (Horsfield 1931j, p). Nonetheless he was careful not to appear too important or powerful - his correspondence also hints at the political statement a well-appointed ‘Antiquity House’ could make: ‘Outside it is dreadful – I have never dared to make it smart: barely to keep it in repair lest it shd [sic] cause resentment + grumbles that I was spending Antiquity funds on my own behalf – so it remains ruinous looking as a camouflage to the inside’ (Horsfield n. d. 1931b).

As a single man, it was easy for Horsfield to live simply. Before his marriage he took bohemian living to heart at Jerash – his bachelor home was filled with camp beds, basic furniture, and only five blankets to distribute to overnight guests (Horsfield n. d. 1931b). Anticipating the arrival of a wife put him under pressure in a new way – to transform ‘Antiquity House’ from campsite to a family home where guests, both official and unofficial, might be entertained in some comfort.

George Horsfield’s pre-wedding letters convey a glimpse into the requirements and logistics of starting an ‘official’ life in Transjordan. Working as an official (including Antiquities inspector positions) meant residence in the country. For the brides-to-be, this meant coming into Transjordan as a ‘selected immigrant’ (Horsfield n. d. 1931b). Further, as Agnes Conway and George Horsfield were married in the Middle East, Conway was required to bring a form from England certifying that banns had been called there, or to wait for a set period to become a resident. Marriages between British subjects in Transjordan had to be recognised by the British authorities, which meant a civil ceremony conducted by the British Resident in Amman (Horsfield n. d. 1931b, 1931i, j, l).

As Anthony Kirk-Greene shows, handbooks were created to provide helpful hints and guidance for those in colonial service in British colonies in West Africa (1999: 163–180). They offered detailed advice on a wide range of topics, from how and where to acquire supplies and equipment, to amusements in the field. The practical arrangements for official (and archaeological) life in Transjordan can be found in Horsfield’s correspondence, as he instructed his bride-to-be on what supplies to bring with her. This was a marriage between archaeologists11 – and in that sense Agnes Conway was not one of the ‘Amman ladies’ (Horsfield 1932b) – the wives of British officials in Amman. He stated ‘The polishing + fussing + show that the women out here put into their houses are not worth while – seeing that it forms their main occupation […]’ (Horsfield 1931j). Rather, he instructed her to provide herself with camping equipment, including an Army and Navy Stores’ ‘officer’s valise with leather straps’, three blankets, a Jaeger sleeping bag, a camp bed and a ground sheet, adding ‘The best place I think to deal with is the Army + Navy Stores as they understand packing shipping + costs’ (Horsfield 1931i, l). The Army and Navy Stores were an integral part of imperial life, providing countless men and women with the accoutrements needed to take on foreign postings (see Kirk Greene 1999: 180–182; Sellick 2010: 92). As Horsfield advised:

‘I would suggest that you buy all this stuff at the Army + Navy stores - as they are accustomed to Brides sending stuff out to their new foreign homes.

This stuff will then be shipped after you go – so as to arrive when we have got the necessary certificate. Your gramophone had best be bought in England + can come out with the rest. The Army + Navy also will I imagine pack + send on with the stuff you ordered from them all your personal stuff. Enquire’ (Horsfield 1931o).

While Horsfield told Conway to bring what she wanted to make his bachelor home more feminine, he warned her that:

‘When we shut up the house and leave it – I have to put someone in to care for it – so that what is there will not be stolen or destroyed wh[ich] is more or less successful. ‘Moth + Rust’ rats + mice are powerful agents + it is maddening to come back to a mattress full of young rats! But it has happened […]’ (Horsfield 1931i)

Alongside their travels and archaeological work, there was a certain amount of socialising in Amman and Jerusalem. Horsfield declared: ‘You won’t want v much in the way of clothes – you must have some because we are sure to be asked out a lot in Jerusalem’ (n. d. 1931b). The British Resident in Transjordan Colonel Charles Cox, the Assistant British Resident Alec Kirkbride, the Judicial Advisor C. A. Hooper in Amman are among the people who appear in Horsfield’s correspondence. In Jerusalem there was the archaeological crowd – John Crowfoot and his wife Molly Crowfoot who were at the helm of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, the Reverend scholars of the Ecole Biblique, and various British officials in the Palestine Government – most notably the Chief Architect of the Palestine Department of Public Works, Austen Harrison, and Stewart Perowne of the Education Department (Thornton forthcoming).

The most insightful letters about the local political ramifications of Horsfield’s official life in Transjordan come from the summer after his marriage, which he wrote to his wife before taking leave to join her in England. These letters reveal the tensions of British residency in Transjordan – in Horsfield’s case wrapped up in a power struggle over knowledge, antiquities and land (Thornton 2011b). Horsfield’s position as Chief Curator/Inspector of Antiquities existed within an emerging Antiquities Department in a newly formed state. From what he wrote about his work in Transjordan three layers of administration become evident: the local, the state, and the international. Jerash was a predominantly Circassian community and this was George Horsfield’s ‘local’ context. The state, with Amir Abdullah at the top, had Arab and Circassian representatives (Luke & Keith Roach 1930: 401–404). The League of Nations Mandate added another international layer, with British officials representing the Mandate and advising the state on matters of government. Horsfield’s role was to navigate between these layers, encourage an increase in visitors and facilitate archaeological research being conducted by (international) teams in Transjordan (Thornton in prep, 2012).

It is clear from the correspondence that his position was not viewed entirely with favour by the local populace. The tensions came to a head when, as Horsfield reported to his wife in England, the local Governor of Jerash had accused him of stealing ‘treasure’ from Jebel Rum, as well as colluding with American excavators in the illegal export of mosaics from Jerash (Thornton 2011b). Because the charge was made officially, the British resident investigated. Horsfield vigorously denied all the charges, stating to his wife that:

‘As you have heard me say so often I am a grave cause of suspicion – my mysterious wanderings over the country my poking + prying here and there with secrecy all raise suspicion in every way – so from time to time it culminates in scandal – but this is the worst I have ever known – and even the people in the Department [of Antiquities] have been suborened [sic] – but there is not a word of truth in all of it. But my actions can naturally be misconstrued, with the suspicion that has ever attached to me as a spy.’ (Horsfield 1932a; quoted in Thornton 2011b).

Horsfield’s friend and co-worker Ali, a Circassian from Jerash, also caused political tension. He had an inspectorate post in the Antiquities Department, which was supported by funding from Britain as part of the Mandate system (Horsfield 1932a; Thornton 2011b, 2012). In the wake of the scandal Horsfield recorded in the summer of 1932, he also reported that Ali was being targeted because of his attachment to the British. Horsfield observed that ‘Ali is not loved – for he keeps himself to himself + helps the English – me – he has ‘gone’ English in fact […] anyone who seems more fortunate than the herd becomes the prey of the whole - + they will pull him down by any manner or means’ (Horsfield 1932c; quoted in Thornton 2011b). Ali’s paid position, funded by the British government, clearly caused upset on a local level, and illustrates the mistrust international archaeological work could cause amongst the community within which it took place (Thornton 2011b). The Transjordan government’s desire to promote the archaeological opportunities in Transjordan for scholars and tourists had an impact on the local society – economically, culturally and politically.

Further details on the wider context of Horsfield’s role in the Department of Antiquities are evident in two letters recently found during the course of the Israel Antiquities Authority’s digitisation of the Mandate archives (Horsfield 1931a; Horsfield 1931b). In spring 1931, Horsfield wrote to the British Resident in Transjordan, Charles Cox, asking him to facilitate a collaboration with the men undertaking the survey of Transjordan for the Iraq Petroleum Company’s pipeline east of Azraq. The survey would be going into areas of the country that the Department of Antiquities had not yet explored. In his plan, survey men would report on antiquities they came across during the course of their work, and Horsfield would endeavour to take the necessary steps to ensure they were preserved and recorded. Related to this, the second letter, from Horsfield to R. W. Hamilton in the Palestine Department of Antiquities, communicates his plan to use the Survey men for inspection. These letters show that Horsfield kept in touch with colleagues in the Palestine Department of Antiquities over the documentation and tracking of Transjordan’s antiquities in its volatile northwestern region. They also reveal Horsfield’s role in building a fruitful working relationship between the two countries’ antiquities departments.

A letter from Horsfield published in Palestine Post, a Jerusalem-based English language newspaper issued during the Mandate Period, highlights again the difficulties of his work. In December 1934 a Palestine Post editorial had accused the British Mandate government in Transjordan of neglect over the research, maintenance and preservation of its sites of antiquity, particularly those sites dating to immediately before, during and after the ‘Christian era’ ( Palestine Post 1934). Horsfield’s response was swift and sharp – he pointed out that the amount of work he could do on these sites was limited to guarding them and carrying out such preservation work as funding would allow. His statement highlights his opinion that a general ‘craze for the bronze age’ was holding scholars’ and funders’ attention, to the detriment of sites from later periods (Horsfield 1934).

These two not-unrelated episodes illustrate the measures taken to ensure the recording of sites and antiquities that were difficult to facilitate logistically with limited funding.12 Here, Horsfield relied on cooperation from both government and private companies to gather information. Overstretched inspectors on small budgets could not have eyes on all places at all times. Further, the place of the antiquities inspectorate in Transjordan as part of the British imperial network is evident, providing another angle of experiences to add to the increasing number of analyses of varied British imperial roles (both formal and informal) overseas (e. g. Lambert & Lester 2006 and also see a recent examination of Margaret Murray and Lankester Harding: Thornton 2014).

The Foreigner

The final part of this exploration of Horsfield’s identity relates to the way in which he saw himself. His letters to Conway reflect a sense of distance from Englishness and English life. Horsfield makes this distinction, phrasing it as a contrast between ‘civilised’ England and ‘barbaric’ Transjordan, from the outset of the correspondence. This is evident in his instructions to his fiancée on the kind of ring he wanted her to have: ‘It will be barbaric – suitable for my Transjordanian wife’ (Horsfield 1931d), ‘[…] not one of those shining things – small + insignificant – but large + lustrous + barbaric’ (Horsfield 1931g).13 Transjordan he described to her as:

‘a far off wilderness’ […] ‘don’t be in any illusions about your future – this place is hell. Yet a pleasant hell if you have a stout soul. I love it! I enjoy the battle to live – the effort that it has to be put out every time you want anything. Things so simple in England are hard to gain here. I feel that I am dazed when I come back again to England + it takes time for me to adjust my mind’ (Horsfield 1931f).

The life of an antiquities inspector essentially meant existing within two parallel societies – the British/European expatriate and scholarly community, and the local diggers, landowners, looters, politicians, notables, policemen and guards who in their various ways affected the antiquities of the region. While other archaeologists who were excavating at particular sites would be in the country for only part of the year, antiquities inspectors lived there for extended periods. Horsfield explained this life to his fiancée in dramatically emotional terms:

‘I dreamt all night about you + the ‘crime’ I am committing in bringing you to this awful place. I wonder if you really know what it means – do you realise the horrors of a cage from which there is no escape no relief […] How are you going to support the lack of contact with your friends which means so much to you? […] You think you are quite a normal person because you live in normal conditions following certain conventions which you have always known + wh[ich] in a large measure guide the conduct. Imagine all these removed […] they will all be removed + you will have to invent new ones in their place’ (Horsfield 1931j).

As a government official and an archaeologist, Horsfield developed an understanding of language and cultural codes that he could apply to the multiple spheres in which he worked. This knowledge is evident in Horsfield’s correspondence – one example being an anecdote in which a local priest came to bless Horsfield on his impending marriage as he lay ill with fever: ‘When I was stewing in the blankets the Orthodox priest came to me + said ‘Embarak’ – may you be blessed! Which is a common salutation when you have something new - a coat – a mare – or a wife!’ (Horsfield 1931i). Certainly Horsfield considered himself a ‘foreigner’ when in Britain; he wrote to Conway: ‘you don’t realise how orientalised I am!’ (Horsfield 1931j, 1931r).

It is clear that he developed relationships in Transjordan and Palestine that were the most meaningful of his life. Horsfield collaborated closely with members of Jerash’s Circassian community in his archaeological work. As they embarked on their excavations at Petra in 1929, Agnes Conway noted in a letter: ‘Mr Horsfield is the easiest possible person to work with + live with + great fun. He adores his Circassians + living with them in the Camp’ (Conway 1929). When he wrote to his fiancée about their plans for the wedding, he expressed his desire to get away from the expected formality of British engagements – ‘I think the Circassian way is best seize the desired by force carry her off and then negotiate with the family’ (Horsfield 1931c). As he announced his engagement to his friends this dual affinity becomes clear – on giving the news to his friend, the Circassian sub-Inspector Ali, he wrote: ‘When I told Ali he kissed me on both cheeks. I told him I was bringing him a sister!’ (Horsfield, 1931f).

Nevertheless, his familiarity with an ‘other’ way of life did not change the fact that Horsfield, and most other Europeans, were foreigners in the East. He ruminated on these differences, and the potential of blurred lines between Eastern and Western approaches in a letter to Agnes:

‘I wonder if you will acquire a sempieternal [sic] patience – when you are up against these orientals whose minds and doings are all in the negative in active opposition or inverted literally the cart before the horse. They demand an elastic patience wh[ich] I nave not ever on tap. I try to imagine you here wrestling with absurd problems wh[ich] never arise in a civilised place – but wh[ich] are part of the struggle to live in the East […] The problems are so many of them infantile that I sometimes think it is mostly probably my own fault arising from a deficiency in ideas of proportion – so many things one fears to let go – for one goes + the ‘malesh’ spirit in the saddle – that is the spirit of ‘why bother?’ then comes the decline which you find amongst orientalised Europeans – who marry Levantine wives!’ (Horsfield 1931m)

While Horsfield’s correspondence often expresses the boredom and frustrations of his official life, it is also clear from his letters that he enjoyed living in Transjordan (Fig. 8). Archaeological work provided him with intellectual and social stimulation, allowing him to carve out a life for himself that differed drastically from his pre-war experiences, and existed somewhere in between official/British and local. This is perhaps most obvious in images of him, which show him adopting some of the outward trappings of his local surroundings – through his headgear (Figs 9a, b).

A photograph in the Horsfield archive of Ali at Irbid, Transjordan. (Copyright UCL Institute of Archaeology).

a) George Horsfield wearing a keffiyeh. b) George Horsfield wearing a Circassian papakha.14 (Copyright UCL Institute of Archaeology).

Conclusion

This examination of George Horsfield’s life and career as an official shows the complexities of colonial/imperial administrative life in an antiquities department. Although research into the history of these antiquities departments is increasing in various forms (e. g. Abu el-Haj 2001; Bernhardsson 2005; Gibson 1999; Goode 2007; Guha 2011; Reid 2002; Thornton forthcoming, 2011b, 2012) there is significant scope for further detailed analyses of antiquities departments and inspectors within the wider imperial administrative framework. Historians of empire have traditionally favoured subjects such as land rights and settlements, agricultural and technological developments, medicine, education, and social issues in imperial or colonial history. Departments of antiquities (relatively low in the pecking order in imperial estimates) have received far less attention outside of the field of archaeology. However, as Guha points out in relation to the history of the Archaeological Survey of India, many government departments were directly or indirectly involved in the work of the antiquities services: public works, education, railways, customs, and judiciary among others (2010: 38).

Scholars have examined routes into colonial or foreign service (e. g. Collins 1972; Kirk-Greene 1999: Ch 2; Mangan 1982; Thornton 2011b), but there was no set route to becoming an antiquities inspector. The most important qualities needed were appropriate scientific knowledge, and being the right person in the right place at the right time, with the right connections in the archaeological (and political) community. Knowing the right people and being known by the right people was crucial (Thornton 2011b). Biographical sketches such as Green’s (2009) investigation of the archaeologist P. L. O. Guy’s life and legacy in the Palestine Department of Antiquities, and those of Weigall (Hankey 2001) and Carter (Reeves & Taylor 1992) in Egypt, point to the intensity of the relationship that antiquities inspectors had with the region in which they worked. This relationship may have been fraught with tension, but unlike other archaeologists who came to sites for more limited periods (and took objects back to their countries of origin through the then legal arrangement of the ‘division’), the Antiquities inspectorate were involved at a basic level in the protection and management of sites in situ, the storage and/or exhibition of finds in local or regional museums, and in facilitating preservation and accessibility of sites and antiquities for future generations (Thornton 2012).

Through the medium of Horsfield’s life, this article seeks to situate archaeologists within a local imperial context – and to read their histories in that context through their archives. The correspondence analysed here provides only a partial view of the life of one antiquities inspector. It is a highly personal and emotionally driven view – the words of a lover to his betrothed, filled with, as he phrased it ‘what is passing through my mind’ (Horsfield 1931m). However, it allows us to question how ‘official’ archaeologists’ relationships with the regions they worked in and people they worked with differed from those archaeologists who excavated seasonally, and to examine how the infrastructure for archaeology and the relationships evolving from this framework can be read in terms of imperial history. Horsfield’s correspondence from Transjordan reveals how one archaeologist’s experience could reflect multiple identities, and how the archaeologist is not just excavator (and exporter) but also official, local, foreign, colonial, immigrant, transnational. (Fig. 10)