- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Rethinking palliative care in a public health context: addressing the needs of persons with non-communicable chronic diseases

Read this article at

Abstract

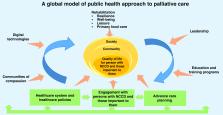

Non-communicable chronic diseases (NCCDs) are the main cause of morbidity and mortality globally. Demographic aging has resulted in older populations with more complex healthcare needs. This necessitates a multilevel rethinking of healthcare policies, health education and community support systems with digitalization of technologies playing a central role. The European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Aging (A3) working group focuses on well-being for older adults, with an emphasis on quality of life and healthy aging. A subgroup of A3, including multidisciplinary stakeholders in health care across Europe, focuses on the palliative care (PC) model as a paradigm to be modified to meet the needs of older persons with NCCDs. This development paper delineates the key parameters we identified as critical in creating a public health model of PC directed to the needs of persons with NCCDs. This paradigm shift should affect horizontal components of public health models. Furthermore, our model includes vertical components often neglected, such as nutrition, resilience, well-being and leisure activities. The main enablers identified are information and communication technologies, education and training programs, communities of compassion, twinning activities, promoting research and increasing awareness amongst policymakers. We also identified key ‘bottlenecks’: inequity of access, insufficient research, inadequate development of advance care planning and a lack of co-creation of relevant technologies and shared decision-making. Rethinking PC within a public health context must focus on developing policies, training and technologies to enhance person-centered quality life for those with NCCD, while ensuring that they and those important to them experience death with dignity.

Related collections

Most cited references76

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Practice guidelines developed by specialty societies: the need for a critical appraisal.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found