- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

JAHA Spotlight on Psychosocial Factors and Cardiovascular Disease

research-article

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

Psychosocial factors, such as stress, adversity, socioeconomic status, depression,

and anxiety, are associated with overall health and with cardiovascular health in

particular. In this issue of the Journal of the American Heart Association (JAHA),

we have featured a group of articles that explore different aspects of the complex

relationships between psychosocial factors and cardiovascular health. Importantly,

psychosocial factors have different prevalence among different demographic groups,

and as such, may be key for addressing disparities in the development of cardiovascular

disease (CVD) and its morbidity and mortality.

Disparities in cardiovascular health between blacks and whites have existed for some

time. In this Spotlight, Tabb and colleagues used novel methods to explore spatial

heterogeneity in racial differences in cardiovascular health in the United States.1

They found that blacks consistently have worse cardiovascular health compared with

whites and that these racial differences exist across the nation, even after considering

residency in the Stroke Belt. These findings highlight the need for geographically

based interventions and policies to address disparities.

Stress can come in many forms. Heikkilä and colleagues evaluated job strain in nearly

140 000 patients with no previous hospitalization for peripheral artery disease and

found that job strain was associated with an increase in the risk of hospitalization

for the disease.2 Although stress has been associated with the development of myocardial

infarction and stroke, this study is novel because it demonstrates stress is also

associated with adverse peripheral artery disease outcomes. In another study, Glover

and colleagues evaluated the association between goal‐striving stress, the stress

from striving for goals, and CVD.3 Goal‐striving stress is a psychological phenomenon

related to striving for upward mobility and awareness of having little success and

may have affected blacks for decades. Using the JHS (Jackson Heart Study), they found

that a quarter of the study population had high levels of goal‐striving stress and

that among women, this was associated with a lower risk of stroke but a higher risk

of CVD.

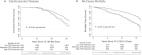

Pierce and colleagues used the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults)

study to perform a large longitudinal cohort study to evaluate the association between

childhood adversity and the long‐term development of CVD and the risk of death among

geographically and racially diverse participants (47% black).4 With over 30 years

of follow‐up, they found that self‐reported childhood adversity was associated with

an increased risk of death and CVD events. The study highlights that childhood is

a critical developmental period for the development of CVD and risk of death over

the lifespan. Of note, following adjustment for demographic, socioeconomic, clinical,

and psychological factors, the risk of CVD events was no longer significant, suggesting

that these factors are mediators of this relationship. The accompanying editorial

by Barr discusses education as perhaps the strongest mediator.5 Low education levels

are associated with higher rates of smoking, a present‐fatalistic perspective, and

social networks that affirm such behaviors and perspectives.

Stress and psychological factors may act through many different complex mechanisms.

One premise is that stress and adverse experiences predispose to behavioral risk factors,

such as smoking, substance use, poor diet, and sedentary lifestyle. Those with poor

psychosocial health may also have limited access to care and insurance. Physiologic

mechanisms are also at play and include abnormal inflammatory and neurohormonal processes.

Stress may also induce elevated blood pressure and glucose dysregulation. In this

issue, Greaney and colleagues add to the literature on the physiologic response to

stress.6 They found that among healthy young adults, psychosocial stress adversely

influenced microvascular vasoconstrictor function. Interestingly, this was regardless

of the severity or the emotional consequences of the stress. In addition, Yano and

colleagues found that sleep‐disordered breathing was associated with higher blood

glucose levels among blacks.7

Although stress may lead to increased morbidity and mortality from CVD, psychosocial

well‐being may be protective. Goldmann and colleagues found that among patients who

survived a stroke, the perception that they can protect themselves from having a stroke

was associated with greater blood pressure reduction at 1 year.8 Positive health beliefs

may reflect optimism and self‐efficacy. To the contrary, Miller and colleagues evaluated

youth who achieved upward socioeconomic mobility and found that improving financial

conditions was associated with improved psychological well‐being but worse cardiometabolic

health.9 This study highlights that psychological well‐being and cardiovascular health

are not always aligned.

Poor cardiovascular health and, in particular, experiencing a traumatic medical event

may lead to psychosocial distress. Pasadyn and colleagues found that, among patients

who survived an acute type A aortic dissection, nearly a quarter screened positive

for posttraumatic stress disorder, with 44% reporting feeling on guard, watchful,

or easily startled.10 Similarly, Johnson and colleagues evaluated mental health among

patients who experienced spontaneous coronary artery dissection and found significant

rates of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder.11 They also found

that emotional and social quality of life was better among those with higher resiliency.

These studies highlight the importance of screening patients with these conditions

to refer them for further treatment of mental health and suggest that resiliency may

be protective. Although less traumatic, patients with adult congenital heart disease

experience ongoing health issues, interactions with the healthcare system, and perhaps

short‐term medical events. Carazo and colleagues found that the prevalence of depression

was nearly 20% among patients with adult congenital heart disease and that depression

was associated with increased all‐cause mortality, hospitalization, and systemic inflammation.12

Those who were depressed had lower education, lower physical activity, and higher

substance use, again raising the possibility that behaviors and education may play

an important mediating role in outcomes.

Additional research is needed to better understand the complex associations between

psychosocial factors and cardiovascular health and whether these factors can be modified

to improve outcomes and reduce disparities. In this Spotlight, Shabatun and colleagues

report the rationale for the Morehouse‐Emory Center for Health Equity, a study designed

to identify factors that predispose blacks to either increased risk or resilience

from CVD.13 In addition to exploring neighborhood and environmental factors, they

plan to focus on personal factors, including psychosocial, socioeconomic, health behaviors

and beliefs, and stress and risk profiles, and their association with prevalent and

subclinical CVD. Their goal is to elucidate new strategies and key points for effective

interventions to improve CVD outcomes in black communities. As part of this work,

they plan to randomize participants to a behavioral mobile health plus health coach

or mobile health only intervention and follow up for improvement.

Psychosocial factors and cardiovascular health are closely tied. As such, it is important

to recognize psychosocial factors and these associations as we work to prevent CVD,

treat patients with known disease, and improve both psychosocial well‐being and cardiovascular

health for all. This group of articles adds to our understanding of the epidemiology

and underlying mechanisms between psychosocial health and cardiovascular health. Finally,

it is important to understand the extent to which psychosocial factors contribute

to disparities in cardiovascular health and evaluate interventions addressing psychosocial

factors with the goal of eliminating these disparities.

Disclosures

Dr Peterson receives grant funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

(R33HL143324‐02).

Related collections

Most cited references13

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Analysis of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Depression, Anxiety, and Resiliency Within the Unique Population of Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection Survivors

Alexis Johnson, Sharonne N Hayes, Craig N. Sawchuk … (2020)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Association of Childhood Psychosocial Environment With 30‐Year Cardiovascular Disease Incidence and Mortality in Middle Age

Jacob Pierce, Kiarri N Kershaw, Catarina Kiefe … (2020)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Sleep Characteristics and Measures of Glucose Metabolism in Blacks: The Jackson Heart Study

Yuichiro Yano, Yan Gao, Dayna A. Johnson … (2020)