- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

The ethics of doing nothing. Suicide-bereavement and research: ethical and methodological considerations

Read this article at

Abstract

Background.

Valuable trauma-related research may be hindered when the risks of asking participants about traumatic events are not carefully weighed against the benefits of their participation in the research.

Method.

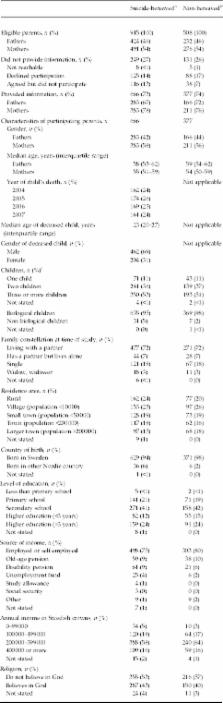

The overall aim of our population-based survey was to improve the professional care of suicide-bereaved parents by identifying aspects of care that would be amenable to change. The study population included 666 suicide-bereaved and 377 matched (2:1) non-bereaved parents. In this article we describe the parents' perceptions of their contacts with us as well as their participation in the survey. We also present our ethical-protocol for epidemiological surveys in the aftermath of a traumatic loss.

Results.

We were able to contact 1410 of the 1423 eligible parents; eight of these parents expressed resentment towards the contact. Several participants and non-participants described their psychological suffering and received help because of the contact. A total of 666 suicide-bereaved and 377 non-bereaved parents returned the questionnaire. Just two out of the 1043 answered that they might, in the long term, be negatively affected by participation in the study; one was bereaved, the other was not. A significant minority of the parents reported being temporarily negatively affected at the end of their participation, most of them referring to feelings of sadness and painful memories. In parallel, positive experiences were widely expressed and most parents found the study valuable.

Related collections

Most cited references19

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Hospitalization for mental illness among parents after the death of a child.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found