1. Introduction

In the last decade, disability arts has been recognised as a powerful source of activism and aesthetic innovation – what British visual artist Yinka Shonibare described as the ‘last remaining avant-garde movement’ (Bragg, 2007). This recognition reveals how artists with lived experience of disability are producing new combinations of form, content and politics and engaging spectators in provocative reflections on the way we relate to each other in the public sphere. Yet, even as the critical impact of disability arts has grown, current mainstream approaches to policies, plans and protocols to increase access and support of Australian disabled artists are failing to have a similar impact.

Prior to the events of the global pandemic in 2020, which saw a stunning lack of support for the entire arts sector in Australia, including performing artists struggling to ‘pivot’ their practices to online platforms, increased funding to support disabled artists was becoming available (Hadley, 2017a). Coupled with calls to open historically exclusionary mainstream Australian theatre and theatre-training institutions to disabled artists, many producers, directors and performers are now working with disabled artists for the first time. Key companies like Back to Back Theatre and Restless Dance Theatre are celebrated, programmed in major events and venues and invited to participate in training of new generations of performers (Hickey-Moody, 2009; Grehan and Eckersall, 2013; Hadley, 2014). This celebration of selected companies notwithstanding, the majority of disability arts practice occurring in Australia – professional practice by independent companies and practitioners and community, recreational and therapeutic arts practice – occurs outside the mainstream. Australia Council, Census and other data consistently show that disabled artists remain underrepresented in the mainstream (Hadley, 2017a).*1 This raises the question, as Amanda Cachia has said, as to whether there ‘is room for a revision of art history and entirely new representations and art experiences through the funnel of the ghettoised disability label within alternative spaces?’ (Cachia, 2013: 258).

Indeed, while leading arts organisations voice commitment of the right to make, speak back to exclusion through and enjoy the arts – as articulated in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability (Article 30) – less than 40 per cent of Australian arts organisations have a Disability Action Plan. As such, the overwhelming majority of organisations do not formally articulate a commitment to disability awareness training, employment, participation or access (Arts Access Australia, 2019, 2020). Industry-wide, few arts organisations employ disabled artists, or programme disability arts as part of regular seasons, rather than as part of one-off special initiatives or partnerships (Hadley, 2017a; Hadley et al., 2022; Hadley et al., forthcoming 2023). As the 2017 Making Art Work report made clear, while 4.3 million Australians identified as disabled, only 4,231 disabled artists and 3,063 disabled arts workers moved beyond recreation, volunteering or other ‘serious leisure’ (Patterson, 1997) engagement to achieve semi-professional or professional employment in the arts (Throsby and Petetskaya, 2017; CofA, 2018). As a result, the 9 per cent of Australia’s professional artists that identify as disabled earned 42 per cent less than their non-disabled counterparts (Throsby and Petetskaya, 2017: 151) – a gap that has in fact increased in the decade since the launch of Australia’s first National Arts and Disability Strategy (2009).

In light of these systemic failures, we share here findings from ‘The Last Avant Garde’ project, which set out to investigate the aesthetic strategies used by disabled artists from around Australia, focusing primarily on the performing arts broadly defined – drama, theatre, performance, dance and related practices.*2 The project brought together a team of d/Deaf, disabled and allied artist investigators, working with state-based arts access organisations and workshop leaders, at six sites around Australia. The team invited artists identifying as d/Deaf, disabled, neurodiverse, having lived experience of a medical or mental health condition, or otherwise being part of the disability arts community to be part of a series of inclusive arts workshops. If they wished, they were also invited to participate in inclusive narrative-based interviews about their work – to learn more about the realities of working in the sector. The groups taking up the invitation varied from around ten in smaller states, to more than forty in larger states, and included a combination of emerging, mid-career and established artists primarily from the independent performing arts sector. The call did, however, draw artists from across dance, music, visual arts and creative writing, and many participants had multiple experiences and skill-sets.

Our intention in this article is to provide mainstream arts makers and mainstream arts educators insights into what these d/Deaf and disabled artists said about how they are devising innovative models of collaboration. The overwhelmingly disability-led initiatives these artists are involved in support sophisticated ways of negotiating access and integrating disability aesthetics into training, devising and production processes. We contend that relational innovations in disability arts practice – the techniques that allow disabled artists to form collaborations with a spectrum of different bodies and minds by negotiating different spatial, temporal and processual perspectives, abilities, dependencies and preferences – remain largely invisible to mainstream arts makers. We conclude that understandings of the ways disabled artists leverage disability culture, space and time to work towards trusting collaborations should be the foundation of future training, production, programming, employment and leadership opportunities in the Australian Arts sector.

The findings from the creative workshops, conversations and reflections with disabled artists around Australia as part of the Last Avant Garde project provide the material for our analysis. Through a series of workshops in Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne, Hobart, Adelaide, Perth and Alice Springs, local d/Deaf and disabled artists were invited to share elements of their creative methods with local participants. The two-day workshops at each location provided the practical in-depth survey of the field of Australian disabled artists practice that has hitherto been impossible, either in industry reports (Australia Council for the Arts, 2017, 2018) or in our own past scholarship (Austin et al., 2015; Austin et al., 2019; Hadley, 2017a). Together with post-workshop surveys and interviews, the Last Avant Garde research team*3 was able to develop a unique set of insights into the various strategies disabled artists employ when making and devising work.

This research revealed, amongst other findings, three main components of access in disability arts practice:

Logistical access.

The importance of logistical access – provision of ramps, interpreters, hearing loops and other access technologies remains vital. This access component is often the focus in industry access policies, plans and protocols.

Ideological access.

The importance of ideological access – disability inclusive language, awareness of disability discourse and malleable modes of connection in training, rehearsal and production contexts to ensure each artist can participate on their own terms, at their own speed, in their own space. As we have noted in past research (Hadley, 2015), this access component is often in focus in scholarly accounts of disability arts practice.

Methodological access.

By methodological access, we refer to specific models of disability arts training, workshopping, devising, production and presentation processes and the modes of collaboration that prevail in them. For many disabled artists, their preferred modes of collaboration, the modes that produce the innovative aesthetics for which Australian disability arts is celebrated, are built on the languages, beliefs, behaviours, values and modes of collaboration that characterise disability culture – norms built on a shared history of social oppression and a shared history of developing strategies to survive that social oppression (Gill, 1995, 1996; Gill et al., 2003).

One of the key findings of the Last Avant Garde project is that the various elements of access are not well understood and that they each intersect and build upon each other. As this article will go on to explore, the techniques disabled artists deploy to develop trusting relationships quickly during the workshop processes are fundamentally connected to individual and collective lived-experience. As such, integrating commonly held disability culture norms enables disabled artists to build trust with fellow artists and long-term allies. This is in contrast with mainstream arts processes – even those that provide logistical access infrastructure and an overarching ideological commitment to access – wherein dominant cultural modes of non-disabled collaboration still prevail, or where extensive physical, psychological and emotional effort to explain disability culture modes of collaboration is still required (Whateley, 2019; Hadley, 2020). This is because, we suggest, such negotiations and interactions between a spectrum of different bodies and minds rely on the ability to be flexible to various ‘speeds’ of participation and connection. Paradoxically, we suggest, to work towards quick-trust, collaborators must first be able to work at different speeds and pay attention to slow-time.

Other than those who have had the benefit of longstanding allyship with disabled artists − witnessing the way these methods underpin disabled artists’ aesthetic practice − few have deep insight into how disabled artists leverage crip-culture, space and time to work through desire, fear, vulnerability and reciprocity towards trusting collaboration. In this article, we take a step towards addressing this issue, exploring how disabled artists integrate crip-culture into their aesthetic methods and revealing why combining the methodological dimensions of access alongside the logistical and ideological dimensions of access is vital to the Australian Arts sector achieving greater success with future access policies, plans and protocols.

2. The Challenge of Accessing the Mainstream Theatre Industry

The ways in which theatre and theatre training institutions have been ‘hostile’ (Johnson, 2012) to the interests of artists with disability are now well understood. Theatre has long used disabled characters as symbols, metaphors and plot devices to signify deviance, deficiency, trauma, pity, overcoming and inspiration to its spectators. It has long called on non-disabled actors to ‘crip up’ to play these roles – a practice that, as Carrie Sandahl says, recalls ‘the outdated practice of white actors “blacking up” to play African American characters’ (Sandahl, 2005: 236). Theatrical representations have, as a result, remained smooth fictional surfaces, undisturbed by the factual reality of the disabled body. Employment discrimination has ensured disabled artists lack access to the training, employment and leadership roles required to intervene in theatre’s continual circulation and confirmation of stereotypes.

Though timelines vary across the US, UK, Europe and elsewhere, the disability rights movement and the parallel disability arts movement have protested these problems since the 1970s (Cho, 1980; AIHW, 1993). In Australia, arts programmes evolving out of schools and institutions for d/Deaf and disabled people did exist as far back as the 1970s, but the practice accelerated following a festival to celebrate the International Year of Persons with Disability in 1981. Internationally renowned companies like Back to Back Theatre emerged in the 1980s, the first fora, conferences and research from funding agencies took place in the 1990s, and the first National Arts and Disability Strategy (2009) was launched in the 2000s. The disability-culture-based methods that Australian theatre and performance makers have been developing since the 1980s (over forty years of innovation), have not been documented in detail – with the exception of key companies like Back to Back Theatre and to some degree Restless Dance Theatre.

In Australia, as in the US, UK and Europe, accounts of why disabled artists still struggle to gain traction in the mainstream have still consistently cited the so-called deficiencies of the artist: inability to slip neatly into the fictional role, inability to play multiple roles, inability to play before-and-after sequences in ‘overcoming’ storylines, lack of stamina, lack of commercial appeal and cost of infrastructure changes (ramps or hearing loops), resource (interpreters), or system (timelines, schedules, breaks) accommodations (Ellis, 2016). The core difficulty often lies, as Sandahl says, with ‘the concept of “neutral,” the physical and emotional state from which any character can be build. Actors who cannot be “cured” of their idiosyncrasies to approach neutral may be considered physically and emotionally “inflexible,” unable to portray anyone other than themselves or those like them’ (Sandhal, 2005: 256). The result of these inabilities – logistical, ideological and methodological – is that disabled artists remain excluded from mainstream practices.*4

This systemic exclusion is compounded by the typically ad hoc basis by which traditional theatre-making processes are ‘adapted’ to accommodate the bodies, communication styles and capacities of disabled artists. As Sarah Whatley (2019) argues, the need to make reasonable accommodations for access for disabled artists frequently involves an exhausting new negotiation with a range of arts, disability and social services stakeholders each time an access need is considered. It is not surprising, then, that our own research reveals similar challenges (Hadley et al., forthcoming 2022; Little et al., 2020). As such, while some key disability performing arts companies have broken through to find a place for themselves in the mainstream, most artists and companies continue to operate under the radar of the rest of the arts industry. These artists deploy their own distinct processes and methods, albeit as they continue to fight for voice, agency, opportunity and authority over how their stories are told on the main stage.

3. Inclusive Theatre-Making Methods

Terms like ‘accessible arts’ and ‘accessible theatre’ are now well understood in industry and in the scholarly field. To date, however, studies of the methods d/Deaf and disabled artists use to train, develop and present theatre remain few – at least compared to the many studies of problematic mainstream representational practices, problematic mainstream industrial relations practices, and the positive, prideful and/or political representations disabled artists produce to counter them (Hadley, forthcoming 2022). There are numerous case studies of key international companies such as Graeae Theatre and key Australian companies such as Back to Back Theatre, along with individual scholar-artist accounts of their own projects. Yet the closest the field has to a meta-level analysis of approaches and methods which goes beyond the work of these individual companies is field leader Petra Kuppers’ (2014) textbook on disability arts and culture methods, a wonderfully practical and useful text based on a wealth of experience. This text offers techniques all artists and artists-in-training can employ. What is noticeable about most studies of accessible theatre, to date, is that they typically focus on specific scholar-artists’ experience of adapting theatrical techniques. They focus on the way voice, movement, play or performance activities need to be adapted to incorporate sign language, captions, audio descriptions, hearing loops or relaxed performance conventions to include different bodies and minds and/or more frequently to make theatrical presentations legible to different audiences. They often focus on solutions specific scholar-artists and their collaborators have found to specific challenges, rather than overarching principles. As we have noted (Hadley, forthcoming 2022), they also focus typically on adaptation for specific groups of d/Deaf, blind or neurodiverse artists, not the broad community of disabled artists and/or disabled audiences. For example, Cohen (1989), Taylor (1995, 1999), Turner and Pollitt (2002), Kochar-Lindgren (2006), Ganz Horwitz (2014) and Richardson (2017, 2018) provide analysis of Deaf and sign language interpreted theatre, Synder (2005), Udo and Fels (2010), Whitfield and Fels (2013), Cavallo (2015) and Kleege and Wallin (2015) provide analysis of audio description in theatre and Fletcher-Watson (2015), Simpson (2018) and Kempe (2019) provide analysis of relaxed theatre.

If accessible theatre is theatre that has ‘fully integrated access for d/Deaf, blind and disabled spectators and performers built into the artistic structure of the play’, as Colette Conroy says (2019: 47–48), then the questions of ideological access (in focus in analysis representation and/or self-representation), the questions of logistical access (in focus in accounts of theatre captioning, interpretation and audio description) and the questions of methodological access (in focus in more recent efforts to emphasise integration of disability culture into theatre-making methods), need to be combined (Hadley, forthcoming 2022; Hadley, 2015; Conroy, 2019; Kuppers, 2014). Creating inclusive theatrical training, devising and production methods are not – or at least are not simply – about identifying and developing direct one-to-one equivalents for extant techniques to suit different bodies and minds, delivered via assistive devices. Expecting that practice can otherwise sit and unfold according to ‘modified’ standard theatre methods is problematic. This approach – adding access features to extant theatre methods, not adapting the methods to be disability inclusive from the outset – operates according to what Dupré (2012) calls an assimilation model which integrates disability into mainstream culture, or, at best, a pluralisation model, which tolerates difference in mainstream culture.

In a theatre context, existing training models adapt voice, movement, dialogue, improvisation and performance tasks in perhaps well-meaning attempts to allow disabled performers to mirror their non-disabled peers. In the end, however, they shoehorn disabled artists back into ableist mainstream methods, rather than expanding methods to be inclusive of them. They fall straight back into the now-criticised medical model of disability, which is an individual model of disability, casting disability as an individual problem to be cured or overcome or, if this is not possible, tolerated, accommodated and integrated through adaptive technologies and techniques. In other words, they still cast disability as a deficiency in the individual artist, not in the culture designed to exclude that artist. A better approach, for Dupré (2012), is a disability culture-based approach. This approach recognises and respects the values, norms and preferred modes of collaboration that prevail in disability culture, developed over time, based on disabled people’s shared experiences of exclusion from culture, education, employment and politics, shared experiences of negotiating that exclusion, and shared ways of being in the world (Gill, 1995, 1996; Gill et al., 2003; Kuppers, 2014: 61).

Integrating disability culture into theatrical method embraces disabled artists’ desired modes of collaboration – how they want to work, in themselves and in relation to others, in training, devising, rehearsal and the aesthetic piece eventually produced. It elucidates how they want to negotiate vulnerability and create trust and how they want to manage mixed communication modalities to produce work that is aesthetically, stylistically and symbolically meaningful, on their terms (Hadley, forthcoming 2022; Conroy, 2019: 53). It thus empowers disabled artists to produce their own dynamic artistic representations, not just ‘adapted equivalents’ of what their non-disabled peers produce through traditional representational methods. Integrating disability culture thus, for Dupré, following Peters, establishes ‘disabled people as subjects and active agents of transformation, decentring the dominant discourse of able-bodied cultural hegemony’ (Dupré, 2012: 173).

For Kanta Kochar-Lindgren (2006), the most powerful examples of this form of practice can invite diverse collectives of artists – with diverse lived experience of different disabilities, genders, sexualities and races and their allies – into what she describes as liminal third space, between dominant and disability culture, which she, speaking from a d/Deaf point of view, terms a ‘third ear’. In this space, she says, diverse artistic collaborators and their audiences can investigate ‘new identities, roles, relationships, modes of interaction, communities, power structures and aesthetics’ (Hadley, forthcoming 2022) beyond those the mainstream assign.

4. The Disability and the Performing Arts in Australia Project

The critical goal for the Last Avant Garde project was to identify what disabled artists across Australia – having found themselves acting as ‘accidental leaders’ (Whatley, 2019) developing their own training, devising and production methods, their own aesthetics and their own career pathways – had actually developed in terms of rigorous, repeatable theatre-making methods.

The project recognised, from the outset, not just the diversity of disabled artists and their practices, but the diversity of contexts across Australia in which these artists would be working – from well-populated metropolitan locations with large established disability arts communities such as Sydney and Melbourne, to smaller urban centres such as Hobart and Alice Springs. For this reason, the project foregrounded a disability-led model, employing local artists to lead workshops and share methods and providing small renumeration for each participant as a recognition of their professional standing and expertise.

As the workshops unfolded, it quickly became apparent that as each workshop leader drew on different artistic practices, deploying different methods of workshopping and modes of performance, each workshop also drew on the skills and differences of the participants. As workshops progressed, new strategies of relation arose, access was negotiated, exercises would take place in a variety of speeds and ways, trust was established (and sometimes lost and established again) and difficulties and vulnerabilities of the facilitators, participants and project team also became part of the process. Over the course of the three-year project, the single common thread was that the disability culture methods, by which disabled artists negotiate vulnerability, trust and platforms for productive, interdependent working relationships between disabled artists and their allies, were particular, adaptable and multi-layered.

Some of the workshops, particularly in the larger cities, focused on theatre-making skills, particularly performing skills. In the Brisbane workshop at the Judith Wright Centre (24–25 March 2019), for example, James Cunningham invited participants to engage in playful, interactive engagement with each other and with the space. He did this first through body-based activities developed via many years training in Al Wunder’s Theatre of the Ordinary and his own performance-making practice, and then through engagement with meaningful objects each participant had been asked to bring along to the workshop. Individual, duo and group improvisation enabled participants to explore their awareness of their body, their presence and their performance for an audience. In a mixed group, including performers, directors, writers and musicians, amongst other artists, Cunningham’s methods enabled both those with limited and those with extensive performing skills to overcome nerves, seek self- and group-feedback on their improvisatory impulses, by themselves, in interaction with others in space and before an audience. Structured, positive and productive feedback was designed to allow each participant to explore the activities in relation to their own practice and make discoveries they could take back to their performing or other arts practice, after the workshop.

Some of the workshops, again particularly in the larger cities, extended from performing skills to choreographic and/or directing skills. In Melbourne (14–15 July 2018), for example, both Janice Florence, from leading Australia disability dance and theatre company Weave Movement Theatre, and Jodee Mundy, from independent production company Jodee Mundy Collaborations, focused on techniques by which d/Deaf and disabled artists can develop distinctive, dynamic self-expression to share stories and subvert stereotypes. In Florence’s workshop, each participant was invited to explore movement sequences, individually and in pairs and then to work together collaboratively to choreograph a short movement piece. In Mundy’s workshop, which was co-facilitated by acclaimed Deaf artist Jo Dunbar, each participant was invited to introduce themselves, to use the objects as stimulus to share something of themselves, in a symbolic way, using their own creative/aesthetic/disability culture community culture modality, as Mundy – a CODA (a child of deaf adults who has grown up a native user of Auslan) would use her d/Deaf culture’s Auslan. Production, sharing and feedback within a very large community of disabled artists – triple the size of the participant group in Brisbane – required quite a good deal of negotiation within a mixed group. This included a lot of conversations and prompts to conversation about the challenges of making work and the challenges of making a career around the work.

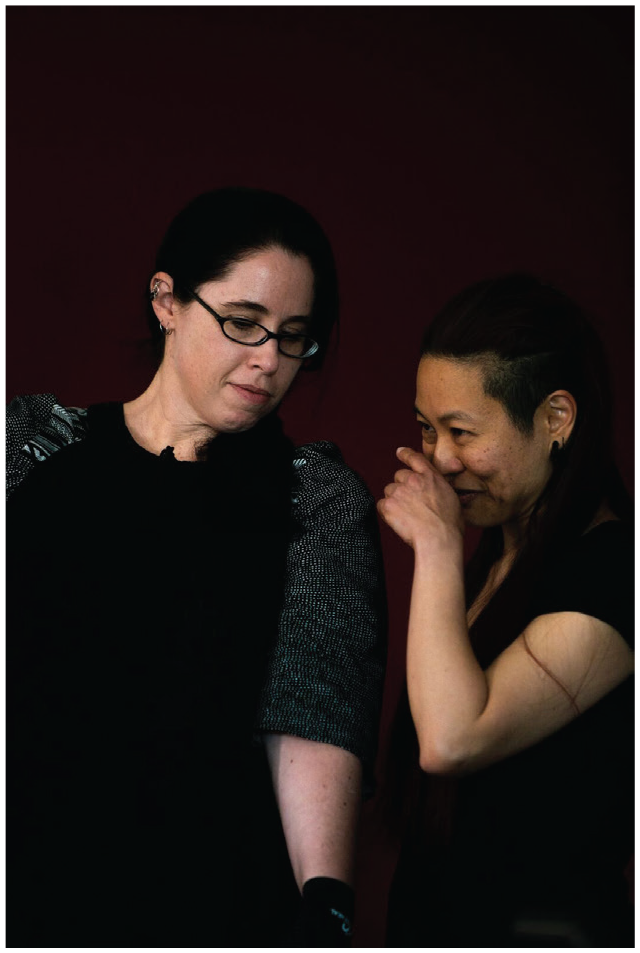

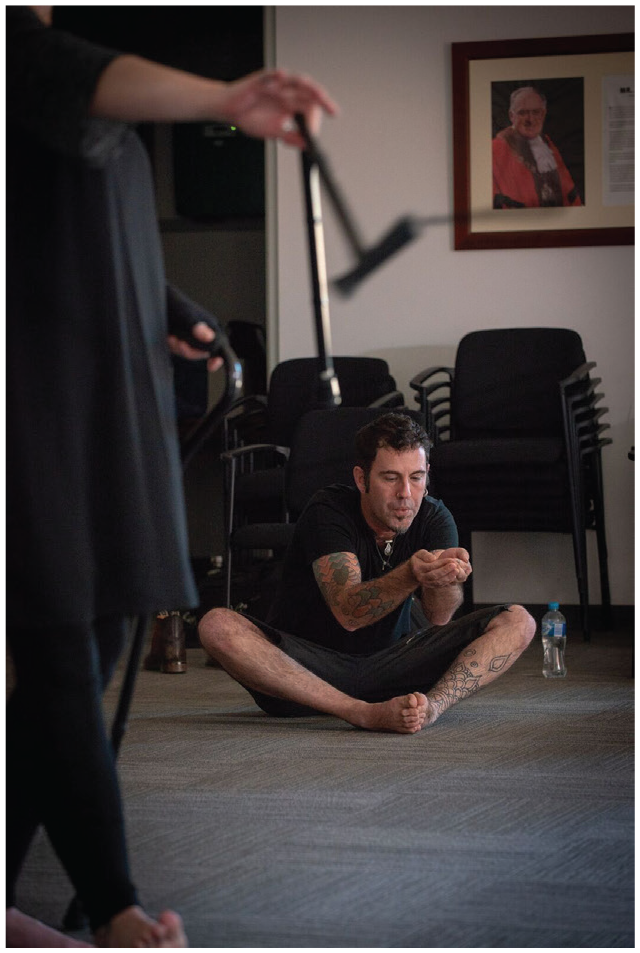

Some of the workshops in the smaller cities became more focused on self-expression, including self-expression of singular or shared experiences of oppression and trauma. In Alice Springs (26 September 2018), Joshua Pether and WeiZen Ho facilitated a workshop called Transmission, inviting participants to share their history through their body, using voice, sound, movement and ritual gesture, this time as part of the Meeting Place arts and disability forum, for just a day rather than as a stand-alone event over two days (Figures 1 and 2). For Pether, who identifies as Indigenous, and Ho, who identifies as culturally diverse, they were interested in the way layers of cultural and familial history intersect with personal history, as part of this workshop.

Undertaken over the course of a day, in two parts, this workshop included a morning session, involving movement improvisation with objects found in the natural environment, then an afternoon session, using voice and movement work to tap into the experience of trauma at being displaced in one’s body/one’s world whether as a result of colonisation, migration or society’s continuing failure to accommodate bodily diversity. This proved quite challenging for the participant group, given the context of a national group of artists coming together at a conference, rather than a local group who might conceivably know each other well. There was, as a result, impromptu negotiation as to how the group might – indeed, if the group could – do the afternoon session together safely. Which, in practice, the group discovered they were able to manage well (using disability culture conventions known to all), despite the group not being one that worked together a lot in a local context.

Accordingly, though the demonstration of the exercise designed to tap into trauma resulted in a rise in emotion amongst members of the group and in the room, the participants were able to note it, discuss it, draw out the emotion and vulnerability, but also provide support for those feeling vulnerable, without suggesting deficiency or over-intervening. This allowed participants to experience the moment and the emotion and move through it together swiftly and safely, to set terms of engagement for the activity, then do it safely, productively and creatively together.

Over the course of the workshops, we observed the ways in which the disabled artists deployed methods developed over decades-long careers to facilitate the work. This included methods used to manage the mixed groups coming together to participate in the typically two-day workshops and to establish and maintain trust during moments of difficulty, as well as methods used to upskill in voice, movement, performance, directing or choreographic technique. In particular, we became increasingly aware of the methods disabled artists used to manage the more confronting moments where participants came to challenges – as a novice performer nervous about presenting work, an emerging artist anxious about career prospects, or a traumatised person recalling histories of oppression – that required navigation and negotiation.

We observed both weaknesses and strengths in methods. As noted, disabled artists have not historically had access to mainstream training, production and presentation opportunities – particularly those disabled from birth, rather than later in life. As a result, many have not had the benefit of formal training, not just in theatre-making methods, but in teaching, facilitating and directing methods used to transmit theatre-making knowledge to others in contexts such as these workshops. Training in therapeutic, recreational, community and/or educational contexts has, for many disabled artists, taken the place of training in inaccessible arts institutions as a precursor to professional employment (Johnson, 2012, 2016; Hadley, 2014, 2015). What became clear, over the course of these workshops, is that while this alternative may provide access to individual artistic skills, it clearly is not providing teaching, facilitating and directing skills. This leaves some disabled artists very clear and confident in their own practice, but lacking confidence to transmit practice to others.

Equally noticeably, however, was the way artists – both those confident transmitting, training and directing others in their mode of practice and those less confident – brought participants into a disability culture space. For these artists, operating according to disability space/time/culture principles provided a method to clarify intent, communicate the needs, interests and desires of each participant, identify moments of vulnerability and navigate a safe path through them, towards both personally and aesthetically productive work. The most interesting aspect of this method was the way in which it enabled them to quickly build the trust required to do potentially difficult work, by – paradoxically – using the slower space, time and relationship negotiation processes distinctive to disability culture. As one participant put it, working in a disability culture context enabled the disabled artists participating to start the process not at A, B or C, or in some cases where it was done well even at D, E or F, but at L, M or N, in terms of trust, understanding and respect.

5. Quick Trust in Slow Time

What we observed, through these workshops, was the way in which disability culture as method produces swift trust, in an inclusive theatre-making process. In the performing arts, where project-based work which brings combinations of artists from within smaller or larger professional networks together for a series of short-term training, development, rehearsal or presentation periods, synchronously or simultaneously, trust is critical (Hadley, 2017b). As Breda McCarthy (2006: 47) has noted, the relative scarcity of funding, jobs and job security in this project-based industry and the high personal, financial and artistic stakes attached to the work, creates a competitive climate which is not naturally conducive to trust. It is not legal contracts, as much as desire to please prospective collaborators, employers and critics within the network, to bolster reputation and future job security, that leads performers, directors, writers and producers to behave in trustworthy ways in this industry (McCarthy, 2006: 48).

Crucially, McCarthy finds Meyerson, Weick and Kramer’s (1996) concept of ‘swift trust’ useful to explain why artists so quickly start displaying and expecting others to display trustworthy behaviour in short project-based engagement in the performing arts. Expectation that trustworthy behaviour will be rewarded may not follow the ‘rational’ trust principles Zucker and collaborators (1996) see operative in more conventional organisations, in more conventionally structured industries, but – for performing artists – operating this way is necessary to ensure ‘the show goes on’. For experienced artists, McCarthy observes, ability to enact ‘swift’ trust is enhanced by what Starkey, Barnatt and Tempest (2000) call ‘latent trust’, where success running past projects becomes an indicator of reliability in running present and future projects this way.

The difficulty for disabled artists, of course, is that a long history of employment discrimination and exclusion does not lead to latent expectation that swiftly stepping in and trusting the traditional theatre-making process a director proposes will produce the desired results, either for short-term success with the workshop or rehearsal, mid-term success with the show’s run, or long-term success with their career. Disabled artists’ experience does not lead them to expect that good performance in networks will lead to the same good results their non-disabled peers expect – trust – that they will see. In fact, Australia Council, Census and other data affirming they are employed and earn less clearly confirms disabled artists should not trust that they will see this. For most disabled artists, attempting to explain, discuss, or demonstrate – from A all the way through to Z – why they feel uncertain, uncomfortable, unsafe or slow to trust within a conventional theatre-making process where no disability culture concepts or methods are operative can be difficult.

A lack of disability culture or methods of making impacts upon the entire process of creation. This impact is partly because, within non-disabled culture, the labour of having to continually educate, advocate and innovate falls onto the disabled artist. Disabled artists may need to explain why a proposed communication, movement, space or time choice is not working; why a proposed collaboration choice is not working; why a proposed representational choice is not working; or why the choice makes an artist uncomfortable (Hadley et al., under review 2022). While such discussions may be a part of many artistic processes, the experiences of disabled artists suggest that the difficulty of these discussions, commonly taking place in non-disabled spaces, are compounded by fear that collaborators may dismiss disabled artists’ concerns about lack of access, bias or prejudice as ‘a one-off miscommunication, misunderstanding, mistake, as bad luck, or a sign of unsuitability for the industry, rather than a pattern, pointing to a systemic bias’ (Hadley et al., under review 2022). Mainstream theatre makers, unfamiliar with the history of oppression disabled artists share, may struggle to make the swift leap from A to B to C, bypassing D, E and F, arriving straight at L or even Z. In contrast, these swift jumps are characteristic of how fellow disabled artists and allies with long experience embedded in disability culture may collaborate.

Unfortunately, as Robey and collaborators (2013: 273) in their discussion of developing disability cultural competency in health and medical contexts discover, the long history of unconscious bias towards the medical model of disability and assimilation models of disability access, means some professionals are not just unaware of the way in which disability culture and identity exists as an identity comparable to gender, sexual or racial identity. Some actively argue that disability is not an identity, the lived experience of cognitive or corporeal difference no more significant than a short-term ‘broken leg’-style accident or misadventure anyone can understand. Beyond difficult then, trying to swiftly trust new collaborators enough to explain, discuss or demonstrate concerns arising from/within conventional methods can be triggering, traumatising and disruptive to the disabled artists themselves and to collaborative teams, where the teams lack the disability culture norms to understand and navigate disability-specific concerns the artist is attempting to address.

What the Last Avant Garde workshops demonstrated is the work Australian disabled artists have done to establish alternative collaboration methods, which enable them to develop trust, by deploying disability culture principles into their practices, to support safe relationships among and between disabled artists and allies. Adapting the concept of swift trust to a disability context, we suggest these methods combine quick trust with different relational awarenesses and engagements with time and space. Analysing the Last Avant Garde workshop most focused on performers’ self-expression of trauma and thus most reliant on establishing trusting relationships quickly shows how artists worked to establish trust through engaging in slow time.

As noted, the Transmission workshop, facilitated by Joshua Pether and WeiZen Ho, as part of the Meeting Place arts and disability forum in Alice Springs in 2018, invited participating artists to engage with their experience of being in their body and in the world, as a people with various forms and feelings of trauma as a result of physical, psychological or cultural displacement. Heading into the latter half of the day, WeiZen invited the participants to do a vocal exercise, drawing fundamental trauma and pain up from the belly and WeiZen and Joshua demonstrated this exercise. This drew near instant recognition of potential for vulnerability from some members of the group, one requesting we stop, another querying if there was time to ‘go there’ in the time remaining and others questioning if there was time enough to build trust around such an exercise.

This recognition led to series of disclosures from nearly all participating artists about how they felt about being able to do this, based on their lived experience. Tears, support and readily understood acknowledgements of these issues were offered by the artists and a collective resolution to continue the workshop was arrived at through extended discussion about vulnerabilities and individual experiences. The entire process was characterised by care and a slowing of the pace of the workshop.

Slowness, as we have noted elsewhere, is often misread as a pejorative term. Yet, slow processes of making and producing art are particularly notable for the ways different experiences of time can foreground new aesthetic models based in ambience, fragility, connection and bodily lived experience (Eckersall and Paterson, 2011). In this respect, the slowing down and pausing of the Alice Springs workshop revealed an alternative model of training based in durational awareness and sensory experience drawn directly from a collective understanding of disability culture, history and politics.

In the end, this engagement with slow time and crip culture rapidly brought the group to a place where participants did proceed to do a version of the exercise, engaging places of their performing selves they found useful and relationships with each other so strong that after the workshop they agreed to establish a nationwide online network that continues to grow and function to this day. The activity in this workshop, in a research context, led participants to observe how much more quickly, comfortably and safely they felt they could work through concerns, precisely because they did not have to explain, discuss or demonstrate the full background to the concerns, justify, apologise or deal with offers to stop the whole workshop, offers of sympathy or Samaritanism.

On the one hand, the negotiation of trust was slow, with breaks, gaps, delays, silences and interpretation to suit and support the different modes of embodiment and enmindment in the participating group. On the other hand, however, the negotiation was quick, thanks to the latent trust, born of the shared understanding of disability identity, disability culture and even the disability space, time, collaboration and relation modes supporting communication, which gave participating artists faith they would be able to work interdependently to support each other to move through concerns without adverse consequences in the community or their broader networks. Participating artists felt that the integration of disability culture in this theatre-making workshop and in certain other theatrical training, workshop, devising, rehearsal and production processes they have engaged with, allows them to make intellectual and aesthetic offers, counter-offers and negotiations, without having to over explain, worry about what others will or will not do in response, over explain and overjustify again, or wait for the right moment.

Artists participating in the Last Avant Garde workshops valued the experience of quick trust through slow crip space, time and culture conventions because it enacted the experience disability arts scholar-artists Petra Kuppers has described as ‘interdependency’(Kuppers, 2014; Hadley et al., 2019). The interdependency goes beyond the concepts of reciprocity, collaboration and care discussed in education, social services and rehabilitation research (Barnes and Mercer, 1997, 2003; Harrison et al., 2001). In interdependent relationships, disabled artists and allies work through vulnerability, discomfort, contestation and conflict together, in a disability culture paradigm, sharing the dual burdens of disclosure and care, rather than placing them on the disabled artists’ side the way ‘care’ models can do.

In this way, these safe, respectful, trusting, interdependent relationships also have the potential to become the basis of Kochar-Lindgren’s (2006) third space, between dominant and disability culture, in which diverse artistic collaborators, with different lived experiences of disability, gender, sexuality and race can explore new aesthetic and identity possibilities, beyond the conventional. In the Last Avant Garde workshop in Alice Springs, the development of quick trust, through slow crip culture methods, enabled positive, productive, interdependent relationships between a diverse group of artists, with a range of lived experiences of disability, gender, sexuality and race, to work through precisely this type of discomfort and find a productive creative collaboration. Lived experience of an exposure to disability arts and culture methods, to develop latent experience of these methods, as a basis of understanding and trust, is no more natural than any other lived experience – for disabled artists and their long-term allies, it is learned over time. For disabled artists and their allies, latent experience with these methods is – as McCarthy (2006) flagged in her general discussion of swift, latent and rational trust in the performing arts – important when considering who to work with in projects and collaborations. Given the stakes, distrust for those who exploit or otherwise break faith with these trusting relations can be strongly felt (McCarthy, 2006: 49; Hadley, 2017b).

6. Learnings for an Industry Looking to Engage with Diverse Artists

The Last Avant Garde workshops demonstrate how swift trust works in disability theatre methods. More significantly, they demonstrate why ideological, logistical and methodological access is necessary to ensure theatre practice is fully inclusive of disabled artists. If mainstream theatre producers, directors and facilitators aspire to make their practices fully inclusive of disabled artists and thus ultimately make the industry fully inclusive of disabled artists, engagement with methodological access is a necessity. Integration of disability culture with theatre-making methods is not new – in Australia, it has been occurring in a range of theatre practices running parallel to the mainstream for more than three decades.

The artists involved in the Last Avant Garde workshops were – if formally trained at all – more often from performing arts backgrounds than from visual arts backgrounds. As a result, they were more familiar with applied and community theatre approaches that engage spectators before, during and after the presentation of artwork than with Nicholas Bourriaud’s (1998) concept of ‘relational’ aesthetics that engage spectators during the moment of presentation of the artwork – and thus tended to the former, rather than the latter, in attempts to describe their methods. This said, most sought to engage with social roles, relationships and the norms that define them as a point of departure for their creative practice. Most sought to engage spectators in examination of these social norms. Most sought to engage spectators in questions of the ethics of the way we think, move, speak, communicate and interrelate together. The methodological advances these artists brought, beyond common understandings of ‘relational aesthetics’, were approaches to re-engaging, re-envisaging and re-imagining the social norms that prevail in theatre- and performance-making methods, to enable new ways of interrelating, which span the logistical, processual and ideological dimensions of access. New ways of interrelating that span the conception of the work, creation of the work, presentation of the work, reception of the work and critique of the work. New possibilities that engage with ‘[a]ccess as a creative methodology’ as Cachia (2013: 283), has described it. New possibilities the participants – often engaged in multiple artforms – felt applicable across the arts sector broadly. In museums and galleries contexts, for example, where, as Cachia says, activists can also ‘think beyond the “main event” of the exhibition of objects, where discursive aspects of exhibition programming, such as artist talks, performances, film screenings, symposiums and roundtable conversations are given equal billing to the exhibition, rather than simply adjunct offshoots’ (Cachia, 2013: 259).

The key goal for the artists involved in this research – in achieving social justice aims very much aligned with the researchers’ own social justice aims – lay in making their methodologies more visible, not just to other artists, but also to arts workers, producers, policy makers, teachers and researchers. Which, in their view, required greater connection between the disability arts sector and the mainstream sector. What this research reveals is that the key to understanding these artists’ methods lies in understanding that they do not, or do not simply, adapt voice, movement, dialogue or performance techniques to allow disabled actors to present a ‘best equivalent’ of their non-disabled peers performances. They develop alternative methods, modes of collaboration and modes of expression that empower disabled artists to enter safe, trusting, creative relationships and produce innovative new creative outputs, meaningful in a disability culture context. The Last Avant Garde workshops demonstrated that embedding these concepts in theatrical training, devising, rehearsal and performance processes – be these disability theatre, independent theatre, or mainstream theatre – may offer a path to achieving the inclusion most in the industry hope to see. Inviting would-be allies to experience, be exposed to and train in this expanded range of methods may offer them the opportunity to understand:

shared languages, values, experience of oppressions and experience of services that aim to overcome that oppression, among disabled artists;

shared willingness to negotiate different and at times conflicting, needs, interests and desires among disabled artists;

shared alertness to a range of verbal communication cues (words), visual communication cues (shakes, stutters, tics, delays, displays of emotion) and communication through human and/or prosthetic extensions (interpreters or computers), among disabled artists;

shared willingness to stop proceedings to negotiate as and when needed among disabled artists;

shared willingness to slow, speed, or shift time and space – without excessive justification, explanation or ‘spotlighting’ those making requests – to ensure everyone is ‘in the room’ amongst disabled artists;

shared understanding that ideas, communications and content may mean something different in disability culture to what they mean in dominant culture, as part of acceptance of what people say, without requiring justification, or attempts at correcting, amongst disabled artists; and

shared effort to avoiding ‘interpreting’ or ‘translating’ the nuances of multi-modal communication out of different participants’ contributions amongst disabled artist amongst other features of the ground-level crip culture space, time, communication and relational conventions disabled artists incorporate into theatre-making methods.

Exposure to these methodological access conventions may assist mainstream theatre makers in understanding why these are as important as ideological access – control over who tells which stories, when, why and how – and logistical access – provision of ramps, interpreters, hearing loops and other basic infrastructure – in shifting the still problematic arts diversity, inclusion and equity statistic in Australia and elsewhere.

More broadly, expanding discourse on arts diversity, inclusion and equity to emphasise method, as much as ideology and logistics, may benefit a whole spectrum of First Nations, Culturally and Linguistically Diverse, Queer and otherwise diverse artists, looking to convey how and why alternative methods afford greater confidence, comfort and safety, with collaborators who can leap from ‘ABC’ to ‘XYZ’ as well. What the Last Avant Garde research suggests is that, while the swift, latent and rational trust mechanisms operative in mainstream theatre-making may be rational for dominant culture artists, they are less so for historically marginalised artists. Yet, quick trust is possible through the relational innovation of slow time. The onus is on all of us to expand not just our ideological horizons and our infrastructure, systems and institutional horizons, but our methodological horizons, to recognise how we can start building new methods, which have the capacity to create safety and trust for a wider range of artists, as part of the path to a more inclusive industry.