1. Introduction

In Ontario, Canada, every year over 74,000 disabled children access services from publicly-funded rehabilitation centres, referred to as Children’s Treatment Centers (CTCs) (Government of Ontario Ministry of Children Community and Social Services, 2020). According to Article 26 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, disabled people have a right to access early rehabilitation and to decide whether to participate in these services (United Nations, no date). Participation in rehabilitation is associated with positive functional outcomes for disabled children (Chen et al., 2004). Participation in the home, school and community can enhance developmental outcomes for children and provide them with skills needed to transition into adulthood (Larson, 2000; Gorter, Stewart and Woodbury-Smith, 2011; Anaby et al., 2014). Given that disabled children experience restrictions to their participation when compared to peers without disabilities, goals related to supporting participation are frequently targeted in paediatric rehabilitation (King et al., 2010; Bedell et al., 2013; King, Rigby and Batorowicz, 2013; Anaby et al., 2014), to optimise health and participation across the lifespan.

Missed appointments have been identified as a challenge in children’s rehabilitation and outpatient services (Phoenix and Rosenbaum, 2015; Ballantyne and Rosenbaum, 2017). Missed appointments occur when a family does not attend a scheduled appointment, either with or without notification of an absence. It is estimated that 15% of ambulatory appointments are missed with the majority (74%) being missed without notification to the rehabilitation centre (Liscumb et al., 2016). Given the frequency of occurrence and the implications for clinical sites (e.g., unable to fill appointment time, resources lost planning for a session, waiting for a client, and following up with a client), this study focuses on appointments missed without prior notification or resulting from patterns of frequent cancellations and late arrival to appointments. Missed appointments are viewed as an inefficient use of clinician time, organisational resources and have potential to negatively impact child well-being (Phoenix, 2016; Ballantyne and Rosenbaum, 2017). As a result, many CTCs in Ontario use discharge policies as a dominant practice for managing missed appointments, which result in discharge from services after a specified number of missed appointments (Ballantyne and Rosenbaum, 2017). While these policies may serve the resource management interests of CTCs, the cause for missed appointments and implications of policies for families also need to be understood.

In a scoping review examining missed appointments in education, health and social services for children 0–18 years old, diverse logistical, cultural and demographic factors were identified as correlates for non-attendance (Arai, Stapley and Roberts, 2014). Barriers at the level of the child, family and organisation have been examined from the perspective of the family as well as healthcare providers (Ballantyne et al., 2015, 2019; Phoenix and Rosenbaum, 2015; Phoenix et al., 2020b, 2020a). At the level of the child, the complexity of health needs has been identified as a barrier to attending appointments (Phoenix and Rosenbaum, 2015; Phoenix et al., 2020b). Mothers of children with cerebral palsy identified that competing priorities related to managing their children’s needs was a barrier to keeping health care appointments (Ballantyne et al., 2019).

At the level of the family, the parent–professional relationship has been identified as a family level factor impacting attendance (Phoenix and Rosenbaum, 2015; Phoenix et al., 2020a). For example, parents’ perceptions of feeling judged for having missed an appointment was identified as a barrier to attending subsequent appointments (Ballantyne et al., 2015, 2019). Supports and resources available to parents (i.e. financial, emotional or informational supports) have been identified as family-level factors promoting attendance (Ballantyne et al., 2015; Phoenix and Rosenbaum, 2015; Phoenix et al., 2020b, 2020a). In a study examining barriers and facilitators to attendance in Canadian neonatal programs, mothers identified that financial concerns were a barrier to attending appointments while provision of information about the service facilitated attendance (Ballantyne et al., 2015).

Issues of low service engagement, such as missed appointments, have been problematised by organisations and policy-makers in relation to aspects of a family’s identity that place them at a perceived higher risk of being ‘hard to reach’ (Winkworth et al., 2010). A systematic review examining literature on ‘hard to reach’ families identified factors such as homelessness, poverty, disability, culture, and parent mental health as having potential to impact engagement in health, education or social services (Boag-Munroe and Evangelou, 2012). Language barriers, navigating systems in a new country, and cultural differences were identified as challenges to accessing services by immigrant mothers of disabled children (Khanlou et al., 2015). The systemic discrimination associated with aspects of identity such as gender, sexuality, or ethnicity may place some families at higher risk for missing appointments. Organisations may compound these barriers and increase exclusion through structures and policies that discharge families after missed appointment.

At the level of the organisation, wait times for service, a lack of continuity between service providers and limited flexibility in appointment times have been identified as organisational factors impacting attendance (Phoenix and Rosenbaum, 2015; Ballantyne et al., 2019). Missed appointments result in families being labelled as ‘no-shows’, ‘hard to reach’ or ‘unmotivated’, terms which place blame on families (Ballantyne and Rosenbaum, 2017). An alternative perspective offered by Boag-Munroe and Evangelou (2012), shifts blame for missed appointments away from families and instead discusses that services might be hard to reach due to service-related factors (e.g., lengthy waitlists, high staff turnover) that make it challenging for families to engage in services. This literature, drawn from public health, medicine, and rehabilitation is reflective of the underlying presumption that children and families benefit from services and therefore access to services should be promoted. When a medical lens is applied, disability is described as impairment that requires intervention to be fixed and subscribes to a singular conceptualisation of normal functioning (Cooper, 2013; Hammell, 2015). Traditional rehabilitation discourse positions disability as an individual-level problem and overlooks the impact of social and systemic structures in creating and sustaining barriers to life participation (Curran and Runswick-Cole, 2014).

In opposition to the dominant impairment focus in the field of rehabilitation, the language of this article aligns with the social model of disability, whereby disability is imposed by societal structures and not by the body of the disabled person (Guenther-Mahipaul, 2015). Identity-first language is purposefully used to align with the position that those living with an impairment are disabled by the barriers encountered in the social environment and not by the impairment itself. The assumed benefits of rehabilitation services for child development highlight problematic notions of an ‘otherness’ associated with children who ‘need’ rehabilitation services when compared to peers who are described as following the expected trajectories of a Westernised discourse of typical development (Cooper, 2013; Curran, 2013; Curran and Runswick-Cole, 2014). This privileges the social construction of normal development as something to be strived for, which is embedded in the culture of providing paediatric rehabilitation services (Gibson, Teachman and Hamdani, 2015). The standard for normal development is perpetuated in the values ingrained in those working in the field of paediatric rehabilitation who are in positions of power to influence practices and structures in this system (Gibson, Teachman and Hamdani, 2015), such as policies associated with managing missed appointments.

The lived experience of disability and voices of disabled children and their families are not privileged in the prevailing developmental and rehabilitation discourses. The exclusion of children and families may perpetuate sustained assumptions by healthcare professionals that families value access to rehabilitation services and subscribe to ideals of a normal development in a way that aligns with how Western society privileges these constructs. Problematically, these assumptions, which pervade the development of dominant service models, practices and policies in the field of paediatric rehabilitation, discount the impact of systemic societal structures on the lived experiences of disabled children and their families (e.g., their experience accessing paediatric rehabilitation services). Instead, they perpetuate a siloed view of disability as a remediable ailment located at the level of the individual. The authors acknowledge the oppressive impact of the medically oriented discourse of rehabilitation and therefore situate their analysis in a rights-based rehabilitation discourse whereby rehabilitation is conceptualised holistically and driven by the choices, values and priorities of disabled people (Shakespeare et al., 2018). Rights-based rehabilitation acknowledges that the value and desire to access rehabilitation varies between disabled people and that not accessing rehabilitation services is a valid choice and the right of a disabled person (Shakespeare et al., 2018).

Grounded in intersectionality theory, this study critically examines access to paediatric rehabilitation services as influenced by CTC policies related to missed appointments. Intersectionality theory examines the intersection between aspects of identities such as race, gender or socio-economics status (SES) with dominant societal power structures that shape a person’s socially created privileged or oppressed position in society (Crenshaw, 1991; Hankivsky, 2012). As an example, in the field of education, the intersection between race and disability has been examined and recognises how the experiences of racialised disabled students differ from white disabled students resulting from the systemic influences of racism and ableism, limiting equity in students’ educational experiences (Annamma, Connor and Ferri, 2012). Intersectionality refutes notions of locating disability at the level of the individual emphasising the impact of systemic societal power structure on participation and lived experience. In qualitative research, intersectionality can be used as theoretical grounding to highlight oppression, generate new knowledge and address power imbalances that perpetuate inequities in health services (Abrams et al., 2020). Through seeking to understand the experiences of diverse groups and critically examining power relationships, intersectionality aims to create change that results in shifts toward a more just society (Crenshaw, 1991; Nash, 2008; Cho, Crenshaw and McCall, 2013). Equity concerns arise when the intersection between identities and power structures (i.e. social practices related to discharge policies) create systemically sustained disparities among who has access to paediatric rehabilitation services.

Applying an intersectional lens, it can be inferred that attendance at therapy appointments is influenced by the socially constructed privilege or marginalisation experienced by a family. This creates potential for ethical tension regarding fair distribution of CTC’s resources between families who have the right to access these services should they choose to (justice) while also providing the best care possible for each family (beneficence) (Blackmer, 2000; Phoenix, 2016). Publicly-funded paediatric rehabilitation organisations experience pressure related to demonstrating service outcomes and efficient use of finite resources. Service pressures may increase risk of systemic bias in organisational practices, such as policies that focus provision of service on groups that are easier to engage and more likely to demonstrate positive outcomes, while limiting service access for those perceived as ‘hard to reach’ (Cortis, 2012). Additional time and resources are needed to attract ‘hard to reach’ families to services (Cortis, 2012). This poses challenges to organisations like CTCs which have more demand for services than their limited resources have capacity to address (Boag-Munroe and Evangelou, 2012; Cortis, 2012; Phoenix, 2016). When resources and efforts are directed towards improving access to care or service use among families that face barriers they typically focus on families who are referred to as ‘hard to reach, vulnerable, marginalized’ (Boag-Munroe and Evangelou, 2012; Nixon, 2019). These efforts problematise the child and family and seek individual-level resilience or capacity building, as opposed to interrogating the structures and systemic inequities that prevent access and engagement in care. This paternalistic approach to ‘helping’ may disempower children and families by presuming they want or need services and require support to access them.

Given that participation in rehabilitation is a right of disabled children (United Nations, 2006), it is imperative that families have access to the available services should they choose to engage with them. Systemic barriers, such as dominant policy practices, preventing families’ access to paediatric rehabilitation services risk infringing on a disabled child’s right to rehabilitation and becomes a social injustice (United Nations, 2006). Currently, little is known about the impact of policy as an organisational factor affecting families’ access to paediatric rehabilitation services. The aims of this qualitative critical discourse analysis (CDA) are to (1) investigate trends in discharge policy for how missed appointments are managed in Ontario’s CTCs (2) critically examine the policy discourse(s) about missed appointments and how they may impact families’ access to services and (3) facilitate organisational change through developing recommendations for equitable policies to optimise attendance and service delivery continuation for all families. These aims are realised by answering the following research question: In Ontario’s publicly-funded paediatric rehabilitation sector, what is the discourse about missed appointments and the potential impact on families’ access to services for their children?

2. Methods

In a critical theory research paradigm, dominant cultural thoughts and social practices are examined and reconceptualised (Eakin et al., 1996; Kincheloe et al., 2011). Critical research acknowledges the influence of power relations on the acceptance of dominant social practices and privileging certain groups over others in our society (Kincheloe et al., 2011). Critical theory aligns with the transformative aims of this research to develop equitable policy recommendations that support families’ efforts to access services they desire.

CDA is a qualitative approach that applies a critical lens to the analysis of text-based language (Janks, 1997), such as the language of discharge policies. Discourse can be conceptualised as a system of statements grounded in a social context that create and sustain patterned ways thinking (Lupton, 1992). CDA highlights the role of text-based language in shaping and sustaining social practices (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2011), such as CTCs using discharge policies to manage missed appointments. In CDA, new knowledge prompting changes in inequitable social practices is generated through examining power imbalances between privileged and oppressed groups (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2011; Fairclough, 2013).

Norman Fairclough’s well-developed CDA theory and methods have been used in rehabilitation and policy analysis (Taylor, 2004; Jorgensen and Phillips, 2011; White and Cameron, 2015; Pedersen and Kristensen, 2016). Use of Fairclough’s methodology promotes trustworthiness when used with interdisciplinary theories to inform study procedures (Shenton, 2004; Taylor, 2004; Fairclough, 2013).

This study is guided by Fairclough’s four-stage dialectical–relational approach to CDA (Fairclough, 2013). This framework was selected because the stages support the researcher in both critically interpreting data as well as creating new knowledge, which satisfies the study aims of developing equitable policy recommendations (Fairclough, 2013). The four stages of Fairclough’s methodology are as follows: (1) focus upon a social wrong (i.e. aspects of social systems that, if not addressed, have potential to negatively impact peoples’ well-being); (2) identify obstacles to addressing the social wrong; (3) consider whether the social order ‘needs’ the social wrong; (4) identify possible ways past the obstacles (Fairclough, 2013). Although the stages are presented in numerical order they do not have to be followed in sequence (Fairclough, 2013). The iterative process for completion of this study as guided by Fairclough’s CDA methodology is described below.

2.1 Stage 1 – Focus Upon a Social Wrong

This stage of Fairclough’s CDA methodology encourages the researcher to select a topic of research that, when examined critically, is linked to a social wrong (Fairclough, 2013). Integrating transdisciplinary theory and literature with the topic of research supports the development of what Fairclough terms an object of research, which allows the researcher to deepen their understanding of social processes associated with the identified social wrong and potential implications for peoples’ well-being (Fairclough, 2013).

In this study, the identified social wrong centres on the potential for discharge practices, as outlined by policy documents, to impact families’ rights to access paediatric rehabilitation services. This study was completed in the context of publicly-funded paediatric rehabilitation in Ontario, Canada. In Ontario, paediatric rehabilitation services funded through the provincial government are available to children and youth under the age of 19 through CTCs (Government of Ontario Ministry of Children Community and Social Services, 2020). There are wait times associated with accessing services and despite CTCs providing a cumulative total of over 750,000 visits in a year, thousands of children remain on the waitlist unserved (Empowered Kids Ontario, 2016).

The social wrong addressed by this study was identified through the first author’s (MR) experiences implementing these policies while working as an occupational therapist in Ontario’s publicly-funded paediatric rehabilitation system. In an effort to promote trustworthiness in this work, MR employed critical reflexivity and transparency about her position in relation to the context and data (Finlay, 2002). In author MR’s clinical experience and perception, some families disproportionately experienced barriers to attending appointments, often leading to discharge from services in accordance with organisational policy. Author MR experienced ethical tension when discharging families who missed appointments. Although aware of the significant pressures on CTC resources, author MR was concerned that marginalised families who desired services were being discharged due to systemic barriers inherent to the CTC context. Furthermore, families that did not desire service might feel pressured to participate in rehabilitation given the service providers’ recommendations and the punitive discharge practices encoded in policies. These experiences informed the lens brought to analysis and interpretation of the data.

Fairclough’s approach to CDA emphasises the subjective nature of data analysis and that interpretation is influenced by the lens applied by the analyst as well as the integration of interdisciplinary theory (Fairclough, 2003). Exploring theoretical perspectives and literature in the areas of intersectionality, health equity and family-centred service (FCS) led to constructing an object of research for this CDA focused on examining the impact of policy related to missed visits, on equity in access to paediatric rehabilitation services. Trustworthiness of the process undertaken to develop the object of research was enhanced by using an audit trail to document critical decisions and reflective memoing, both of which were frequently reviewed by senior researchers on the team (Lincoln and Guba, 1986; Shenton, 2004). For example, the first author (MR) who was responsible for leading analysis engaged in reflective memoing about her assumptions and values related to constructs, such as rehabilitation, to be transparent and conscious about her positioning and biases.

2.2 Stage 2 – Identify Obstacles to Addressing the Social Wrong

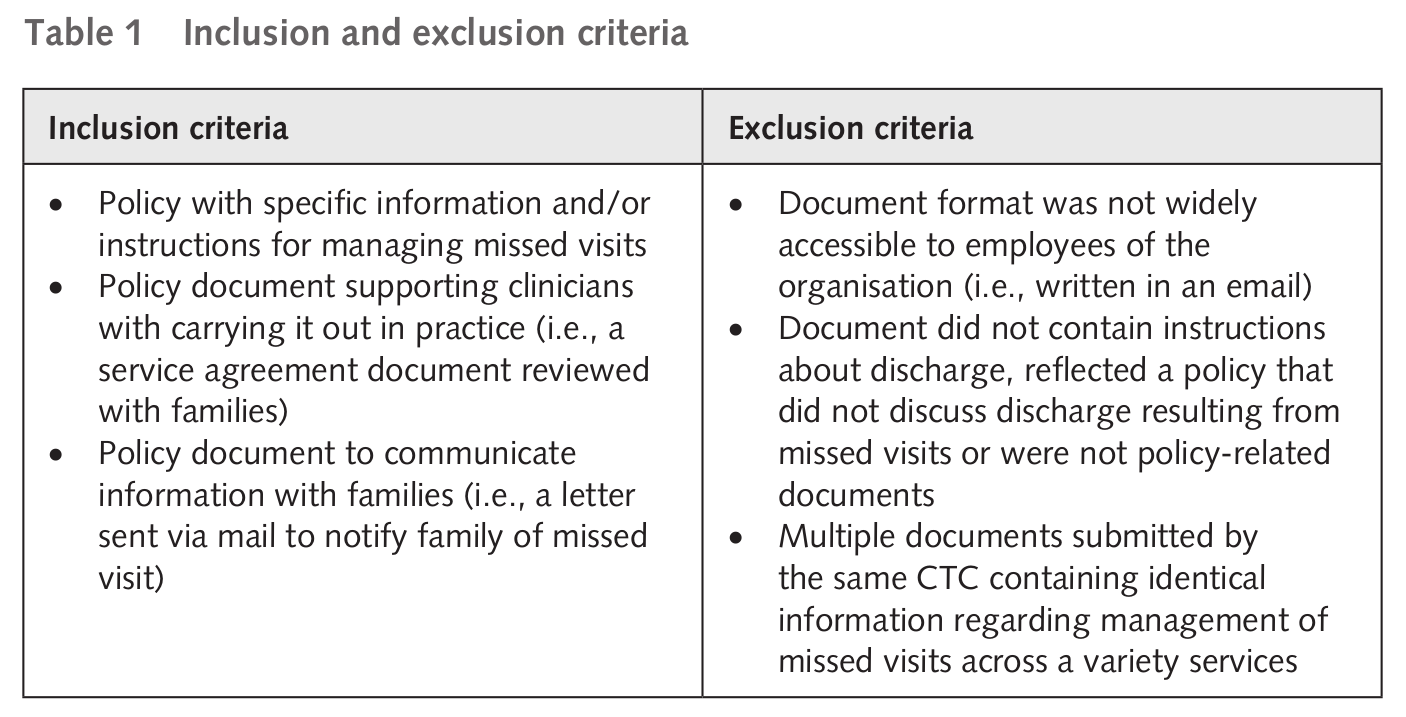

This stage involves selection and analysis of texts to understand how they create and sustain discourse in relation to dominant social practices (Fairclough, 2013). As part of a larger project examining attendance and engagement in paediatric rehabilitation (Phoenix et al., 2020a, 2020b), 21 CTC organisations were contacted through an email sent from the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Ontario Association of Children’s Rehabilitation Services (OACRS, now Empowered Kids Ontario – EKO) that requested each centre’s policy documents related to missed appointments (January, 2016), with two follow-up reminders sent by the study team and the CEO of OACRS (February, April 2016). Centres were requested to email the study team if they updated their policy and procedure documents, this occurred once, and the revised document was included in the analysis. 74 documents were submitted from 18 of the 21 CTCs during the period of January to April 2016, with one additional email received in November 2016 to state that the CTC did not have formal policy in this area. Ethics approval was received from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (project #1006). All documents were de-identified of information linking the data to a specific CTC by an impartial individual not involved in data analysis. Inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) for the data were developed in consultation with the full research team. Included documents were categorised as either ‘Policy’, which included policy documents only or ‘Family Document’, which included documents reviewed with or sent to families regarding the policy. The most common reason (n=18) for exclusion was because the document was a policy unrelated to missed visits. After applying these criteria, 38 documents were included for analysis.

Fairclough’s approach to CDA requires two levels of textual analysis: linguistic analysis and interdiscursive analysis (Fairclough, 2013). Linguistic analysis involves analysing language in text-based documents, which in the case of this study were policy and policy-related documents (Fairclough, 2003). Interdiscursive analysis, whereby patterns from linguistic analysis are examined to identify emerging discourse from the data occurred iteratively and simultaneously with linguistic analysis (Fairclough, 2013). Integrating methods that support interpretation of texts is encouraged in Fairclough’s approach to CDA (Fairclough, 2003). Iterative coding was used to describe and interpret the data (Baezeley, 2013). Microsoft Excel spreadsheets (Microsoft Corporation, 2016) were used to manage coded data.

The following descriptive information was extracted from included documents: document title, person or department that created the policy, year created or revised, document length, document type (i.e. policy or supporting document), definitions provided, specifications related discharge procedures, methods identified to share information with family about the policy, methods used to support families’ attendance, methods used to contact a family after missing an appointment, and any exceptions to proceeding with discharge due to missed visits. As part of textual analysis, initial coding occurred through line by line reading of the data by the first author to label emergent patterns in policy document language (Baezeley, 2013). Further analysis prompted recontextualising initial patterns, to describe distinct FCS, health equity and power relations discourse embedded in policy language and positioned in the dominant discharge practices of the CTC context. Coding memos were maintained to explore the process of data coding and discourse identification, enhancing rigor (Lincoln and Guba, 1986; Birks, Chapman and Francis, 2008).

Interdiscursive analysis was guided by critical theoretical groundings in intersectionality, FCS and health equity. These theoretical concepts guided initial data coding as well as the questions posed of the data to recontextualise codes, identify patterns and extract meaning from the data to describe discourse (Birks, Chapman and Francis, 2008). Analytic memos were used to examine relationships emerging from linguistic analysis and enhance trustworthiness of results (Lincoln and Guba, 1986; Shenton, 2004; Birks, Chapman and Francis, 2008).

2.3 Stage 3 – Consider Whether the Social Order “Needs” the Social Wrong and Stage 4 – Identify Possible Ways Past the Obstacles

There is no prescribed flow for moving through the stages of Fairclough’s CDA methodology; as such Stages 3 and 4 were addressed iteratively and cyclically, moving freely back and forth between them throughout data analysis (Fairclough, 2013). Reflective memos were used to transparently explore the relationship between the first author (MR)’s position in the research on data interpretation (Birks, Chapman and Francis, 2008). Narrative and diagrammatic analytic memos were used to examine data patterns, leading to its interpretation in the context of CTC discharge practices, as described in policy, and the potential impact on families’ access to CTC service (Birks, Chapman and Francis, 2008). Results from linguistic and interdiscursive analyses were examined through memoing to identify possible solutions to address service access barriers (Fairclough, 2013). This level of analysis resulted in developing recommendations aiming to enhance equitable access and service delivery continuation for all families. Trustworthiness of data analysis processes was enhanced through the use of an audit trail, reflexivity and memos as well as frequent consultation with senior researchers on the team about emerging codes, patterns and discourse in the data (Lincoln and Guba, 1986; Shenton, 2004; Birks, Chapman and Francis, 2008; Baezeley, 2013).

3. Results

The results begin with describing trends in the policy documents across CTCs to contextualise the dominant practices used to manage missed appointments. Next, critical analyses of FCS, health equity and perpetuating power relationships are presented. Quotes and examples from the data are used to illustrate the discourses and situate them in the CTC context and the broader systems (e.g., health), policies (e.g., UN Convention on the Rights of the Child), and theories (e.g., intersectionality theory). These systems, policies and theories shape discourses about missed appointments and rehabilitation services for disabled children and their families.

3.1 Descriptive Trends in Discharge Policy for Managing Missed Appointments

15 of the 18 CTCs from which data were collected had formalised policies created between 2008 and 2016 to manage missed appointments. 13 CTCs with included documents had revised at least one discharge policy or policy related document from their initial published form. Of the 38 data documents that met inclusions criteria, 19 were formal policy documents, 3 were documents to support clinicians in sharing information with families about the discharge policy (e.g., service agreement between family and organisation) and 16 were documents sent directly to the family (e.g., letter to family notifying them of missing an appointment).

A variety of procedures were identified to minimise missed appointments including the use of appointment cards, reminder phone calls, reminders by mail, offering families an alternate service delivery method (e.g., change time or frequency of appointments), providing families with organisational contact to proactively cancel appointments and offering interpreter services. 6 CTCs utilised more than one method to minimise missed visits. Some exceptions to following discharge policies were identified including if appointments were missed due to inclement weather, illness, emergency situations, families having to manage multiple appointments, transportation issues, language barriers and unspecified extenuating circumstances.

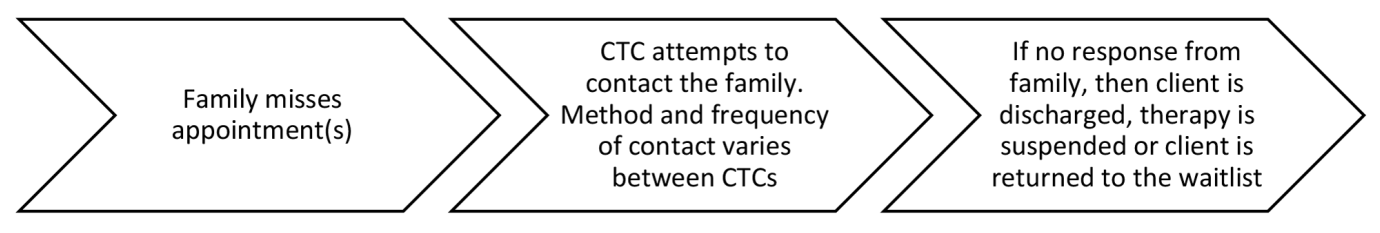

Overall, CTCs vary in the policies used to manage missed visits. Some clear policies exist, however, grey areas leave room for interpretation and flexible application. Despite variability in the details of policies, a common flow for managing missed visits depicted in Figure 1 emerged from the data.

3.2 Family-Centredness Discourse in Policy Documents

Evidence indicates that FCS improves access, health outcomes and family satisfaction with care in children with special health care needs (Kuhlthau et al., 2011). In 2015–2016, as an indicator of FCS, parents’ perception of the care they received was routinely measured using the Measure of Processes of Care at 11 of 19 CTCs (Empowered Kids Ontario, no date; King, Rosenbaum and King, 1996). FCS emphasises parents as experts on their children as well as partnerships between professionals and families (Rosenbaum et al., 1998; King et al., 1999; Law et al., 2003). Problematically, client-centred service (equated to FCS in the paediatric rehabilitation context) has been accepted as a discourse guiding rehabilitation practices with little critical reflection on the evidence for this approach. Who defines what this approach looks like in practice and whether it is successful at achieving the aim of shared power between client and professional has not been examined thoroughly (Hammell, 2013). In paediatric rehabilitation, FCS is intended to empower families to be active agents in directing care and choosing meaningful service options that suit their specific context (Rosenbaum et al., 1998). However, some families may prefer an expert model of care, feel overburdened by the demands in leading their child’s care, or prefer not to access care at all (Phoenix and Vanderkaay, 2015; Pluut, 2016). These choices may not be available to families when FCS is enacted in rigid ways that presume to know and act in families’ best interests. This lens was brought to bear on the analysis of FCS discourse in the policy documents.

A discourse of family-centredness emerged from the language of policy documents analysed. However, despite CTCs mandating the provision of FCS, the language of policy documents analysed did not consistently align with family-centered principles. In the data, FCS is discussed as a singular desirable entity however, this discourse is challenged by language, practices and policies that do not align with traditional FCS values in children’s rehabilitation (Rosenbaum et al., 1998; King et al., 1999; Law et al., 2003).

3.2.1 Explicit and Implicit Representation of Family-Centredness in the Language of Policy

In the data, FCS was at times identified explicitly, such as ‘J provides family-centred practice’ (J-Policy), however more often an implicit meaning of family-centredness was derived from the choice of language used in policy documents describing interactions occurring between the CTC and family related to missed appointments. The intention of providing ‘meaningful service’ (P-Policy) creates an understanding that families need to have an active role in determining what services best fit their specific context. A willingness to collaborate with families and tailor services to optimise access was evident in language such as, ‘Clinical staff work as a team with clients and families in order to provide the type of service required, at a time and location that is appropriate, available and accessible for the client and family’ (L-Policy). Acknowledgement that service needs vary between families is illustrated in this excerpt, ‘H aims to provide services to as many clients as possible, working along with families to support their involvement as their needs dictate’ (H-Policy). FCS is portrayed as a practice that aligns with a rights-based approach to ideally support all families, including those marginalised by systemic barriers, to access services through attempting to empower choice and direction in care. However, given that this FCS discourse is embedded in a culture driven by discourse of rehabilitation and development, the choice for families not to access services is not represented as a ‘meaningful service’ option, inadvertently restricting their right to choose.

Some policies acknowledged the cultural diversity of families and aligning with family-centred principles made policy objectives to ‘ensure communication is understandable to ESL [English as a Second Language] clients/families’ (G-Policy). Exceptions to proceeding with discharge were made if it was felt the family did not understand the policy, for example ‘the termination process is not applicable when communication has not been understood by clients and families’ (G-Policy). Supportive services such as arranging for ‘use of an interpreter’ (J-Policy) or linking family with social work services (I-Policy) were explicitly noted in some policy documents. Exceptions to discharge after missed appointments such as ‘illness’ (F-Policy), ‘hospitalization’ (K-Policy), ‘challenging personal circumstances’ (K-Policy), ‘transportation issues’ (G-Policy), or having ‘multiple appointments scheduled’ (M-Policy) also demonstrated consideration for family context. While concrete supports, such as interpreters, may help families to access care, they are predicated on the assumption that families want to access rehabilitation and may overlook potential cultural differences in views on rehabilitation, child development, inclusion that may underlie choices about care and participation in services.

Use of language like ‘partnership’ (P-Policy), ‘team’ (L-Policy), and ‘relationship’ (J-Policy) further illustrated a desire for collaboration between the organisation and family. In the data, the need for a family’s involvement in service was formalised through procedures mandating discussions between clinicians and family about the shared commitment required from both the CTC and family. Often ‘Families are asked to sign a partnership in therapy letter outlining attendance requirements’ (J-Policy). Partnership or commitment to service agreements were commonly used to share information about discharge policies with families, ensuring ‘both parties [CTC and family] understand their commitment to service’ (M-Policy). It appeared that partnership agreements were presented as family-centred approaches to promote engagement in care. However, upon closer inspection, some agreements mandated parent attendance and outlined consequences of missed appointment such as:

Clients and families are expected to attend all scheduled therapy sessions and to arrive on time. Appointments that are cancelled or missed by the family will not be rescheduled. (B-Family Document).

Other partnership agreements attempted to empower families to initiate conversations with their care team if experiencing challenges with attendance, illustrated in this excerpt from a service guideline document reviewed with families:

Therapists welcome parents to discuss any challenges with attending appointments as other options may be available to better meet my needs. (M-Family Document).

By framing discussions or agreements as a partnership with responsibilities from all parties, an attempt is made to distribute power among all involved in the service relationship. Collaborative generation of solutions as well as inclusive policy statements such as, ‘It is the policy of L to work with families to facilitate client and family attendance …’ (L-Policy), tries to create a dynamic of shared responsibility and power between CTC and family, aligning with embedded principles of FCS in this context.

3.2.2 Policy Language in Conflict with Family-Centredness

A shift toward the CTC holding power over the family becomes evident in the use of punitive language situated in a legal discourse such as ‘A reserves the right after careful consideration to discharge a client from treatment’ (A-Policy) or having families ‘sign a contract’ (D-Policy) related to service expectations. Given the power differential between professional and family created through the choice of punitive language, families may feel coerced into signing these documents even if they anticipate not being able to fulfill the terms, infringing on their right to choose to participate in rehabilitation. Language of the policy documents becomes less congruent with FCS when the choice of language creates an understanding that the family has a less active role in identifying meaningful service options, as illustrated in this quote from a document reviewed with families, ‘We cannot offer other treatment types until the recommended therapy has been completed’ (M-Family Document). Similarly, family-centredness is compromised when families are not involved in generating solutions to missed appointments. In the following excerpt, families are not identified as being involved in meeting to generate solutions:

In the event that missed appointments persist after the plan has been jointly implemented, all involved services shall meet to discuss the appropriate course of action. (H-Policy).

The family is placed in a position of limited power to identify when they feel attendance is becoming a concern as ‘discussion regarding a family’s barriers to attending appointments shall be initiated by the clinician when a clinician believes attendance is becoming a concern’ (H-Policy). These examples illustrate that FCS was adopted by all CTCs without indication of critical consideration about whether it should be adopted or how it may affect client experiences of care. How FCS was enacted in policies may disempower families (e.g., via service agreements that outline actions and consequences). This may decrease families’ right to choose the type of service and service delivery model that fits their cultural values and beliefs, which may include the choice to decline care.

3.3 Health Equity Discourse in Policy Documents

3.3.1 Portraying and Operationalising Equitable Service

Equitable treatment means giving people what they need to best suit an individual family preference or circumstance. Like family-centredness, a discourse of equity emerged from the data explicitly in examples such as, ‘F strives to provide equitable access to client services within available resources’ (F-Policy). When not mentioned explicitly, equity was often present in the implied meaning of the language of policy, as illustrated by excerpts like ‘If the family is faced with challenges to attend, the therapist will determine a different service delivery method to assist the family’ (C-Policy). ‘Expected processes for new clients for O intervention will be clearly documented to provide timely and equitable service.’ (O-Policy) is an example of a policy objective that explicitly mentions equity. However, the procedures written to operationalise this objective depicted a rigid process that each family was intended to move through. This rigid language depicted equality in which every client receives the same treatment, however, an equitable approach would allow for individual tailoring that accounts for the families’ situation, needs and choice.

3.3.2 Making Room for Equity in the Language of Policy

Despite some incongruence between the objective and operationalisation of equitable service in CTCs’ policies related to missed visits, the language used in these documents creates opportunity for health equity through procedural flexibility and examples of going above and beyond to provide families with specific supports needed to access services should that be their choice. Use of flexible language such as ‘careful consideration’ (A-Policy), ‘guidelines’ (B-Policy), ‘exercise discretion’ (H-Policy), and ‘professional judgement’ (K-Policy) creates flexibility for service providers to adapt processes to accommodate families’ unique contexts. Although encouraging professionals to use their individual judgement allows for flexible application of discharge policies, it is important to recognise that individual discretion may be influenced by preconceived negative judgements or unconscious bias based on family identity or circumstance. This could increase the risk of marginalised families disproportionately experiencing barriers to continued service as a result of systemic inequities such as racism, classism or ableism.

Policies enabled service providers to use their judgement regarding proceeding with discharge despite missed appointments, as allowances can be made for missed visits that are ‘deemed reasonable’ (O-Policy), ‘justifiable’ (H-Policy) or ‘valid’ (I-Policy). The power for upholding equity in service is held by the service providers and their value judgement on the validity of a family’s reason for missing an appointment leaves room for bias in application and risks undermining the aims of equitable service. The language in some of the policies depict a commitment to making discharge from services a last resort, occurring only when ‘every attempt to work through hardships or barriers has taken place’ (G-Policy). Equity is also demonstrated through procedural steps aimed at engaging families who have missed appointments by adding resources such as social work services or contacting ‘other agencies or service providers with consent that are part of the client’s circle of care in an effort to engage the family’ (L-Policy). While it may appear equitable to make attempts at understanding a family’s barrier to services and to consider discharge only after problem-solving attempts, we must also consider the inherent value in any reason that a child or family has for missing an appointment and the potential harms in having those reasons judged. While social work services and attempts to work through hardships may be well-intentioned, they may also threaten child and parent autonomy in pressuring families to use services or to worry about the involvement of social work and potentially child protective services.

3.3.3 Balancing Equitable Access to Service with Management of Resources

The policy documents provide flexibility within procedures and encourage actions that support engagement of families who miss appointments while simultaneously advocating for equitable service access for families waiting for service by acknowledging finite CTC resources. Policy language attempts to justify the necessity of discharge resulting from missed appointments due to the need to efficiently manage limited resources. The need to manage waitlists (i.e., ‘M has a lengthy waitlist and thus missed appointments results in delays in other children receiving service’) (M-Policy) and resources (i.e., ‘to ensure the most effective utilization of costly and limited resources, clients are expected to attend appointments …’) (H-Policy) are used as justification for procedures that involve discharge as a strategy to address missed appointments. Service wait times and resource management are mentioned in documents shared with families to illustrate reasons why missed visits are problematic: ‘As resources are costly and limited, clients are expected to attend appointments …’ (H-Family Document). In a letter to families, waitlists were used to justify why the family was being discharged from services, ‘we have many children waiting for our service and therefore [you/client name] have/has been discharged from [name of service] at G’ (G-Family Document). With the reality of finite resources and high demands for service, CTCs attempt to balance service equity for those active in service as well as those waiting for service. However, by advocating for equitable access for both groups, the language of these documents becomes conflicted. On one hand the language allows for flexible interpretation to avoid discharge, while at the same time uses resource management to justify procedures that lead to discharge.

3.4. Perpetuating Established Power Relations Discourse – Creating Power Imbalance Through the Language of Policy

3.4.1 Institutional Power Sustained Through Controlling Access, Differing Expectations for Attending Appointments and Valuing Professional Opinions Over Family Input

Language in the policy documents places value on the judgement of the clinical professional to determine if a family remains in service after missing appointments as illustrated in statements such as, ‘It will be at the discretion of my therapist(s) to continue service’ (M – Family Document). The organisation holds the power to determine what is justifiable for missing an appointment stating that, ‘frequent cancellations without valid reason may result in the child being discharged from a service’ (I-Policy). Language of policy also indicates that the organisation has power to dictate when a family is able to access service, indicating that ‘services can be started again at a future date, when the client/caregiver are able to commit’ (H-Policy). Examples from the data indicate that value is placed on professionals’ opinions regarding when a family needs to access service for their child, such as ‘therapist/consultant felt it was important to see you’ (A-Family Document), which might influence the family to feel as though they must engage in service, limiting their sense of choice. Entrenched in the broader discourses of development and rehabilitation, service providers’ values and beliefs in the benefits of rehabilitation and the ideal course of child development are embedded in the policies. Through use of discharge policies, organisations have imbued service providers with power as gatekeepers that may grant or limit access to services to families. Families are in a relatively powerless position with limited choice in determining if they want service, to miss or pause services, or whether to return to services after a discharge.

The power relations embedded in this discourse emphasise power imbalance through the language used to describe actions taken by professionals to manage missed visits compared to stronger language used to indicate actions required by parents to comply with the process. For example, a policy indicates that a ‘therapist will make a reasonable effort to communicate with the family to discuss the situation by making a special phone call’ (P-Policy) or instructs that ‘the professional should be discussing with the parent/caregiver a different model of delivering service that will accommodate reasons for missed appointments’ (M-Policy). Comparatively, actions required by families are represented by language like ‘must’ (L-Policy) or ‘expected’ (A-Policy), which give a sense of finality and restricted choice. For example, these policies state that the family ‘must be on time’ (B-Policy) and are ‘expected to attend all scheduled appointments’ (B-Family Document). Although nuanced, comparing the language that demands specific actions from families to the suggestive tone associated with the actions of service providers illustrates that power differential can be created and maintained in policy.

Within the policy documents, a dominant view exists related to the organisation’s perception that attendance at therapy appointments impacts child treatment outcomes. This value is illustrated through statements like, ‘your child’s goals will only be met when you come regularly to all appointments’ (H-Family Document). The conceptualisation that attending therapy appointments is necessary for a child’s development is noted in 13 policy documents and is utilised to motivate attendance as well as to explain to caregivers why missed visits are problematic. Statements such as, ‘we are concerned that you may not be receiving the necessary therapy support to promote your child’s ongoing development’ (A-Family Document), or ‘consistent attendance for scheduled appointments will provide the best treatment support for the child and family’ (B-Policy) create the assumption that there is a causative link between attending appointments and therapy outcomes. These claims, however, are not supported by evidence within the policy documents and instead are presented as the accepted viewpoint in the field of paediatric rehabilitation. Upon critical reflection of these statements, they are interpreted as a means to motivate families to attend appointments, however, in reality they may devalue the impact families have on their child’s development and can increase the pressure families feel to attend appointments. Additionally, these values embedded in policy perpetuate normative ideals of child development and disability as an impairment requiring rehabilitation. Parents may experience feelings of self-blame and guilt if they are unable to attend appointments, increasing the power discrepancy between the CTC and family as well as creating barriers to conversations about the family’s values and desires related to services access and outcomes.

3.4.2 Devaluing Family Power Through Language and Expectation

In addition to the language of policies devaluing the family’s impact on child development independent of CTC intervention, the language also acts to minimise the family’s power in the service process. Use of punitive language in policies such as ‘failure’ (E-Policy) or ‘consequences’ (P-Policy) create the sense that the family is expected to act or respond in a way set out by the organisation with procedures in place to follow up if the family does not engage as expected. Statements such as, ‘failure to make contact will result in discharge from the specified service’ (F-Policy) use language to clearly delineate repercussions of a family’s inaction and strips the family of the power to choose an alternate course of action that might better suit their context.

Power imbalance between the CTC and family is also illustrated through language that can be interpreted as making assumptions about the family or labelling them based on their action or inaction in accordance with the institutionally defined procedures for how missed visits are managed. Policy documents use terms like ‘chronic cancellers’ (I-Policy) or label families as being ‘at high risk of cancelling’ (A-Policy) based solely on attendance history. A family’s attendance history leads to further presumptive statements related to their level of commitment to service such as, ‘it appears that services may not be a priority for you at this time and as such, we are discharging …’ (A-Family Document).

Language in policy documents places the responsibility for managing and attending appointments on families stating that ‘clients and families are expected to attend scheduled assessment and recheck appointments’ (B-Policy). Letters are sent to families with reminders that their ‘failure to contact the clinician will result in discontinuation, postponement or discharge from service’ (H-Policy) and associate a family’s level of engagement in service with attendance at appointments as illustrated by the statement, ‘our priority is to provide service to the families who are committed to treatment for their children, as demonstrated by regular attendance at therapy appointments’ (M-Family Document). This language places expectations for how the organisation anticipates a family should act in the service relationship, devaluing family contribution and desires in the service delivery process. Limiting family choice and input in turn limits their power in the service relationship by restricting opportunities for their unique contexts to be acknowledged. This perpetuates the notion that families subscribe to the same assumptions of those in positions of power (service providers), that rehabilitative treatment is beneficial for the development of disabled children.

4. Discussion

The language of CTC discharge policies results in dominant practices that risk infringing on a disabled child and their family’s right to choose whether to access rehabilitation. As a step toward addressing the social injustice associated with restricted access to rehabilitation, recommendations for equitable policies that enable service use are discussed below. Authors of this article acknowledge that families may elect not to use rehabilitation services and that these services are situated in traditional rehabilitative discourse that privileges notions of normal development, remediation, and service provider expertise. This positioning may not align with families’ beliefs, especially when cultural beliefs are explored and systemic inequities that may be experienced in health and rehabilitation are considered. While these complexities are acknowledged, the focus of the recommendations are to provide feasible steps that CTCs can take to shift dominant practices and reconceptualise norms around discharge policy development and implementation. Much work remains in the critical examination of the intersection between service access and barriers imposed by accepted social practices and discourses. Operationalising the recommendations proposed here is a starting point toward encouraging CTCs to reflect on how current practices contribute to the maintenance of oppressive systemic barriers impacting families’ access to their services.

In the literature, FCS is described as a model of care that recognises the parent as a constant in the child’s life, which has been shown to increase parent satisfaction with service, reduce parent stress and increase parent emotional well-being (Rosenbaum et al., 1998; King et al., 1999; Law et al., 2003). Although rehabilitation professions identify client-centred services as a core value in their professions, little information has been solicited from clients themselves to determine what defines client-centred practice or what it means for a professional to practice in this manner (Hammell, 2013). This risks perpetuating professionally derived assumptions about what it means to practice in a family-centred way and about the value families place on family-centred service. While further critique of FCS is warranted, the policy recommendations provided below are situated in the FCS discourse that is common in CTCs.

Given that child development is impacted by family context, FCS calls for the needs of all families members to be supported (Rosenbaum et al., 1998). Raising a disabled child has the potential to increase financial strain, negatively impact parent health, increase reliance on public support and weigh into parents’ decisions related to employment and education (Reichman, Corman and Noonan, 2008). Families report challenges they experience due to systems-related issues, such as navigating disjointed services, advocating for their child’s services and social participation opportunities, and a lack of financial or material supports (e.g., respite services) (Hanvey, 2002; Ballantyne et al., 2015, 2019; Sapiets, Totsika and Hastings, 2020). While these systems-level issues and the impact on families’ finances, health, and social participation may pose barriers to service use, current policies for addressing missed appointments are limited to how services themselves can be modified (e.g., the frequency, time or location of service provision). If FCS is extended to deeply understand families’ lived experience, an intersectional lens may be usefully applied to understand the systemic barriers that limit access to a range of health and social services such as ableism, racism, classism. An examination of these inequities raises different questions about why families may decline service use and points to novel strategies that may support families’ decisions about whether to access services and how to increase the acceptability of those services.

In the policy documents analysed, frontline clinicians are sometimes encouraged to initiate conversations with families who have missed appointments to discuss barriers to attending. However, within the policy documents there is little procedural detail provided to ensure these steps are implemented consistently. Current practices risk missing an opportunity to engage in conversations with families to gather information about their context and gain insight into the influence of systemic barriers on attending appointments. To truly address service access barriers, FCS needs to move beyond modifications to service into the political sphere to advocate for structural and institutional change across multiple systems (e.g., housing, employment, healthcare), a worthwhile but immensely complex venture.

Recommendation: It is recommended that policy development is informed by a family-centred approach that prioritises understanding family needs, values, desire for therapy, and the potential for systemic barriers to influence their care decisions and access. This may enable CTCs to adopt and implement policies that promote families’ therapy-related choices, examine individual and systemic barriers to service use, and to work in solidarity with disabled children and families to address the systemic inequities embedded in rehabilitation, health and social services.

In Ontario, Canada there is a high demand and lengthy waitlists for paediatric rehabilitation services (Empowered Kids Ontario, 2016). CTCs are challenged to make efficient use of limited resources considering both families active in service as well as those waiting for service. Additionally, publicly-funded services are accountable to funders to meet service output targets related to the number of families serviced, time spent waiting for service, and positive therapeutic outcomes for clients (Phoenix, 2016). Both funding and limitations on service capacity have been identified as system-level barriers to families receiving early intervention services for their child (Sapiets, Totsika and Hastings, 2020). The pressure of outcome performance and finite resources may create systemic bias toward discharging families who require higher levels of organisational resources to support continued engagement in services (Cortis, 2012). These perspectives are drawn from dominant rehabilitation discourses that prioritise goal attainment, positive outcomes, and efficiency in service delivery. Ethical tensions may be experienced by children, families and clinicians when they do not ascribe to these values, yet are tasked with enacting the policies that prioritise attendance, progress, parents’ responsibilities in care, and resource allocation between children who are waiting for service and efficient care delivery to those that are already involved (Phoenix, 2016).

Recommendation: Given the potential for ethical tension when enacting policies related to missed appointments, it is recommended that CTCs formalise a mechanism for applying an ethical lens when developing policy. Taking an ethical approach to organisational policy development has been shown to emphasise the shared values of the parties involved and generate policies aligning with organisational values (Ells and MacDonald, 2002).

Intersectionality is inherently concerned about the influence of power relations on creating and sustaining dominant views in society that result in the marginalisation of some groups over others (Crenshaw, 1991; Hankivsky, 2012). Power imbalance in favour of the CTC emerged from the policy documents through language placing the organisation in control of families’ access to service, dictating expectations from families in relation to attending appointments and perpetuating assumptions about the value families place on services. This power differential is sustained by the creation and implementation of policies by persons in a perceived position of power. Power in health policy is described as being elite-focused, whereby power is centralised around particular influential groups (Lewis, 2006). Influence has been identified as important to the health policy process as it impacts which issues are considered during policy development (Lewis, 2006). In the CTC context, organisational structures, such as management and a board of directors, exist to govern the operation of CTCs. This leadership structure places individuals, such as members of the board or the CEO, in positions of considerable power in policy development, meaning that their standing can influence issues addressed by policy.

Given that power in health policy tends to be concentrated within an elite group (Lewis, 2006), it is imperative that methods are employed during policy development to mitigate risk of systemically biasing discharge policy to negatively impact some social groups over others. A demand for increased accountability for public decisions has resulted in increased transparency by decision-makers for processes such as policy development (Gregory and Keeney, 1994).

Involvement of multiple and diverse stakeholders, including groups at risk of systemic oppression, has been identified as critical in the development of public policy (Riege and Lindsay, 2006). Innovative policy alternatives can be developed through the inclusion of stakeholder values (Gregory and Keeney, 1994). Rights-based rehabilitation emphasises the importance of creating space for the voices of disabled people to share their experience, needs and desires regarding rehabilitation (Shakespeare et al., 2018). To achieve improved balance in power between the CTC and family it is recommended that the family voice (including that of the child or youth client) is represented at the stakeholder table during policy development. Family and client input can be included in the development, implementation and evaluation of policies (Carman et al., 2013). Including families and clients as stakeholders provides critical insight related to areas of concern that may impact policy development and assist in setting priorities for the use of limited resources (Carman et al., 2013). Through sharing of lived experience, inclusion of family and client voices in policy development creates the opportunity for deeper understanding of family needs, the value placed on therapy and the impact of systemic barriers on accessing services.

Recommendation: Procedures for the inclusion of diverse family voices and the voices of disabled children and youth should be formalised into CTC policy development processes. Dedicating resources to engage families who have historically experienced barriers to attending appointments will be necessary to promote representation of diverse family and client input in policy development. Proactively budgeting for inclusion supports such as translators and transportation costs is recommended to facilitate diverse engagement (Simons, 2012; Health Quality Ontario, 2017). Purposeful planning is needed to involve diverse groups in policy development (Simons, 2012; Health Quality Ontario, 2017). Developing a plan driven by the priorities, needs and availability of families instead of the organisation supports family and client engagement (Simons, 2012). Creative and flexible methods for collecting input from families and clients who have experienced difficulties sustaining engagement through traditional methods will need to be considered to facilitate their participation in policy discussions. Including families and clients as stakeholders in policy development enhances organisational transparency and mitigates the risk of policy practices negatively impacting access to services for some families and clients over others.

5. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite employing methods to support the trustworthiness of results there are some limitations to this study. Textual analysis focused only on policy documents and did not extend to other CTC documents that might have impacted findings (e.g., strategic plans, culture and value documents). Additionally, this study was completed in the context of publicly-funded paediatric rehabilitation in Ontario, which limits the transferability of results to other settings.

This article provides recommendations aimed at enhancing the development and implementation of policies that support equitable access to rehabilitation services for families who choose to engage with them. Further research is needed to understand the complexities associated with operationalising these recommendations in practice and the steps required to shift policy development practices in this context.

Conclusion

Disabled children and their families have the right to choose to access rehabilitation services. The dominant organisational practices associated with discharge policies related to missed appointments in Ontario’s CTCs, strongly embedded in rehabilitation and developmental discourses, risk disproportionately limiting the choice to access to paediatric rehabilitation services for some families over others. Policy recommendations have been provided to support equitable service continuation and access to paediatric rehabilitation services for all disabled children and their families who choose to engage in them.