Introduction

Deinstitutionalisation of care*1 for people with disabilities in Lithuania started in 2014 when the Minister of Social Security and Labor approved the Lithuanian Action Plan (2014–2020) for the Transition from Institutional to Community-Based Care. This plan aimed to create opportunities for people with disabilities to receive community-based services, including assisted employment, social enterprises, personal assistance, supported decision-making, respite care, and independent living. Thus, independent living was not considered at this stage as an ultimate goal but rather as a set of skills and services that would enable persons with disabilities to exercise choice and control of their lives. However, this process overlooked the critical awareness-raising component in the local communities and increased the risk that investments in real estate by building group homes and subsequent embeddedness in local economies would hinder the transition towards independent living.

A group of researchers from Vilnius University’s Institute of Sociology and Social Work conducted a systematic analysis of deinstitutionalisation for people with disabilities in Lithuania, which focused on a previously unexplored factor: the wellbeing of communities undergoing this process. Deinstitutionalisation was examined as a reconstruction of the entire structure of the community’s social fabric. This reconstruction changes the connections and relations between the main participants in the reform – people with disabilities, the Ministry of Social Security and Labor (hereafter Ministry), social care institutions, non-governmental organisations, municipalities, and communities. Previous research has revealed that people with disabilities have been considered outsiders in the process of deinstitutionalisation and the public and media discourse around it.

Methodology

The researchers used a case study methodology. It involved observation of public meetings between the central government and the communities dedicated to deinstitutionalisation; qualitative and quantitative analysis of the news media coverage of this issue; interviews with persons with disabilities, community members, and social workers; and ecological maps drawn by persons with disabilities and community members. The ecomaps method allowed us to visualise the independence of people with disabilities: how the informants used physical places, what social activities they engaged with in these places, and the independent choices they were able to make. Researchers attended three public meetings organised to inform local communities about deinstitutionalisation. One hundred and twenty-one publications were collected from the most popular national and local online news portals and analysed using quantitative content analysis; additionally, 40 publications concerning the related case of the establishment of community living were selected and analysed using a discourse analysis approach; 35 participants with disabilities and 24 without disabilities designed ecological maps and afterward participated in semi-structured interviews. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Department of Social Work and Social Welfare at Vilnius University.

Analysis

The research data revealed the selective application of the human rights perspective, which did not consider raising community awareness of the right of people with disabilities to independent living (‘awareness raising’ being an expectation of States Parties according to Article 8 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities). Together with this, the need of local communities to participate in making decisions related to changes planned in their neighbourhood was also ignored (Mataityte-Dirziene et al., 2023). Formal communication between officials and the communities was limited to the requirements of the law. For example, neighbours were presented with a signboard on the building site that indicated the beginning of the construction of a group home. The lack of awareness of the rights of people with disabilities, stigma surrounding institutional care (including the construction of ‘smaller institutions’), and lack of communication about the building plans created preconditions for conflicts between the community members and the local authorities.

The research data showed that the media are active and influential participants in the deinstitutionalisation process, affecting the course of the conflicts. However, the media’s interest usually increased when the story to be reported was negative. Although the media reflected the diverse opinions of the main actors, persons with disabilities usually remained voiceless, whereas the stereotypes surrounding them (such as that they cannot live independently) were made public and highlighted. Moreover, because the community members with more positive attitudes towards persons with disabilities were silent, and those with ableist attitudes were more vocal, the whole community was often presented as lacking social responsibility and solidarity. Negative media presentation distorted the image of the resisting communities and often increased their defensive position.

Ecological maps revealed interactions between persons with disabilities, other community members, and the service system, that is, the extent of their independent mobility and opportunities for personal contacts and independent choices. There was little difference between the physical places visited by people without and with psychosocial and intellectual disabilities, including supermarkets, cafés, libraries, parks, and museums. However, their social spaces (i.e. their opportunities to engage in heterogeneous relationships) were little related, which hindered ‘the positive right to develop inclusive environments’ (General Comment No. 5 of the CRPD Committee, 2017). This lack of social interaction and the opposition from some community members hampered the social inclusion and participation of persons with disabilities and restricted the development of their skills for exercising choice and control, which flourish in a supportive and unstructured environment (Mataityte-Dirziene et al., 2023). Information about the building of the group home was delayed in time. Moreover, information about the rights and diverse needs of persons with disabilities and the purpose of the house was absent. Such a narrow approach excluded the possibility of a thorough discussion among the members of the community and representatives of the Ministry about other aspects relevant to independent living, such as access to transport, information, communication, personal assistance, daily routine, employment, personal relationships, religious and cultural activities, sexual and reproductive rights (General Comment No. 5 of the CRPD Committee, 2017).

The central government did not provide adequate information about the changes related to deinstitutionalisation, which increased the level of mistrust in the local communities. People’s attempts to participate in decision-making resulted in protests against the government plans. Consequently, persons with disabilities were turned into ‘scapegoats’ of political conflicts, they were objectified and experienced hostility, and the public discourse was polluted with inappropriate and stigmatising disability-related concepts. Distrust of government decisions and fellow community members did not create prerequisites for community cohesion and hindered the inclusion of persons with disabilities.

For the relationship between government institutions and community members to turn into an equal partnership, independent living must be respected as a right and ultimate goal rather than as a spontaneously occurring by-product of deinstitutionalisation. Opportunities for independence must be created and implemented with the support of local communities. If communities are enabled to influence the timing of the reform, articulate their expectations, and decide how resources will be used, they would be less likely to fight for the preservation of the status quo and would be more motivated to contribute to the independent living of persons with disabilities. Opposing opinions are highly likely in the first stage of deinstitutionalisation, and discussions in the community should be encouraged, thereby creating a necessary space and time to relearn and thus reconstruct attitudes towards neighbours with disabilities socially.

Unfortunately, the process of deinstitutionalisation also lacks leadership by persons with disabilities and their organisations. The reforms’ focus on building or reconstructing living places and ignorance of other aspects of independent living, and the danger of trans-institutionalisation, turned the disability activists into passive observers and critics. As one activist, disappointed with the reform stated: ‘I would never endorse the reform if it intends creating small institutions for ten persons’ (personal communication with a disability activist from the Lithuanian Disability Forum, 2018).

At the political level, a correspondence between the significance of government plans and the time allocated to their discussions with the local communities could lead to greater trust in government decisions. It would diminish tensions between the newly arrived people with disabilities and long-time community residents. On the contrary, the dialogue, awareness, and transparency culture would contribute to the wellbeing of both.

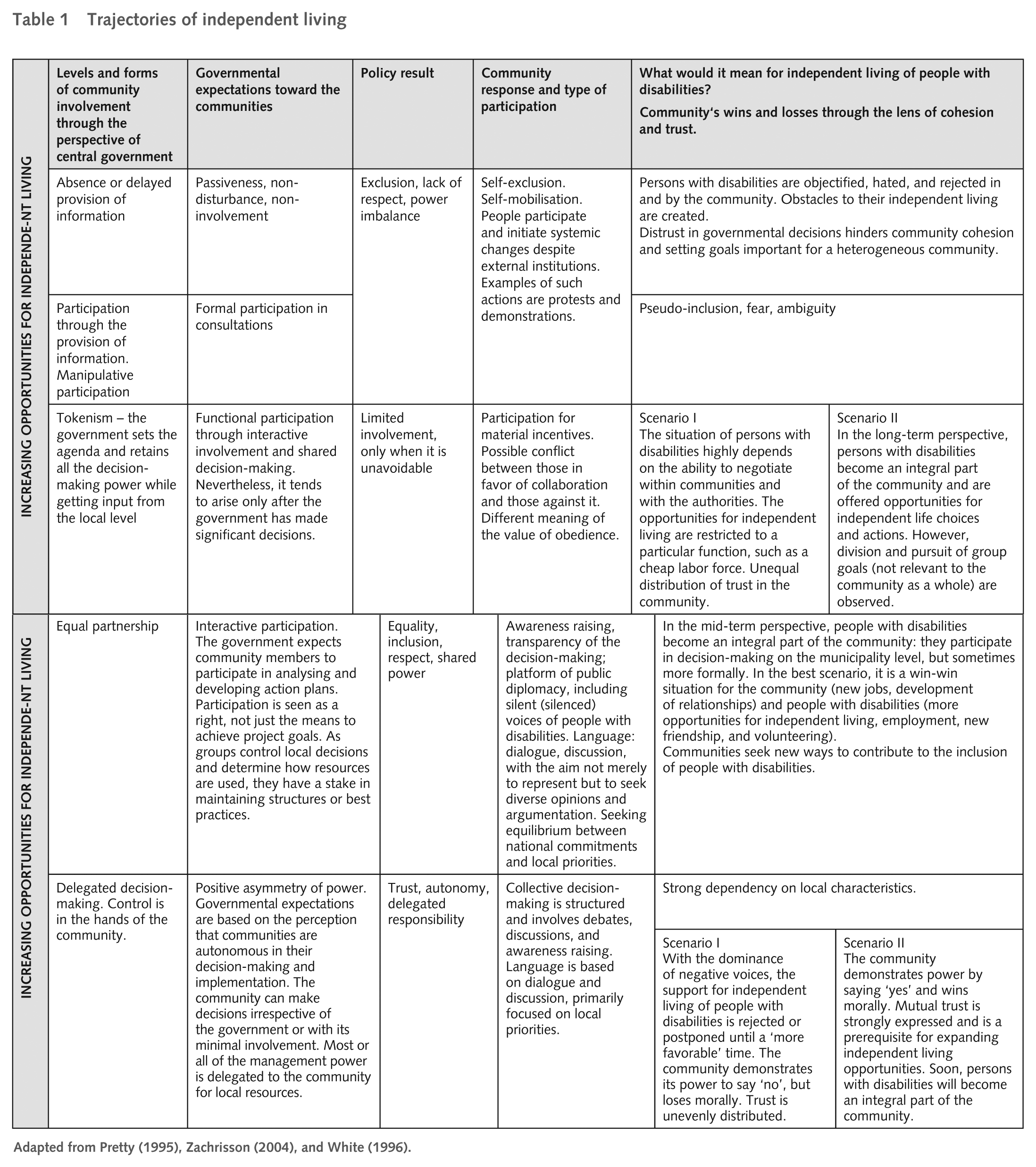

Table 1 is based on the works of three authors. First, Pretty (1995: 1252) distinguishes seven types of participation in development programmes ranging from manipulative participation to self-mobilisation. Secondly, Zachrisson (2004: 13) offers eight types of citizen participation concerning the co-management of natural resources. And thirdly, White (1996: 7–9) analyses different interests and various forms of participation.

Trajectories of independent living

Adapted from Pretty (1995), Zachrisson (2004), and White (1996).

The table summarises the integration of the component of community wellbeing into the concept of independent living. This integration is presented through the following aspects: levels and forms of community involvement from the perspective of the central government; government expectations for communities; policy outcomes; community response and the nature of their participation; the impact of resettlement of persons with disabilities on community wellbeing; and the community’s gains or losses in terms of cohesion or trust.

Conclusions

The research showed that relocation of people with disabilities into the group homes in the community is at best only an intermediate stage towards their independent living; without a thorough discussion with local people, it can end in a lack of trust in the idea of deinstitutionalisation. We can assume that the compromise option of ‘small institutions’ is convenient only from a system-based point of view, but due to its stigma it is not acceptable to local communities and does not open up prospects for persons’ with disabilities to experience a truly independent life.

The research revealed that, paradoxically, independence implies co-dependence on each other, as this co-dependence opens up opportunities for newly arrived people with disabilities to work (for example, being offered a job in a neighbour’s garden), to participate in leisure activities (for example, in a universally designed sports space), etc. For people without disabilities or long-time residents of the community, this co-dependence may manifest in the newly created job places (such as a social enterprise or personal assistance) and, most importantly, a moral sense of community. In our research, the moral sense (‘we are doing the right thing’) and mutual trust emerged as essential prerequisites for creating opportunities for people with disabilities to start living independently. Perceiving one’s community as fostering a culture of choice and control strengthens mutual trust and contributes to the wellbeing of persons with disabilities.