INTRODUCTION

Female genital mutilation (FGM) has received much attention during the last decades concerning reproductive health and has been classified as a violation of human and children’s rights [1, 2, Ford, as cited in Ref. 3]. However, it is not really clear when and where FGM originated exactly, but it can be traced back to Egypt earlier than 2000 before Christ (BC) [1, 4, 5]. Johnsdotter [4] stated that due to the impossibility of collecting enough information and evidence about the migration patterns in the Middle East and Africa and the spread of FGM, it is difficult to ascertain whether the practice of female circumcision had originated in one specific area, and how it scattered and developed over time. However, citing Lightfood, Hanslmaier [6] stated that FGM was also introduced in Europe in the late 18th century as a way to combat masturbation which was seen as a disease or a trigger for a disease.

The WHO [7] has defined FGM as “all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons”. FGM is performed among all age groups from newborn girls to married women. In most cases, the girls and women are cut by a traditional exciser, who often is a female member from the family or a senior woman from their village. The procedure is performed without any anaesthesia or medical personnel using a knife, sharp stone, scissors, razor blade or even the fingernail while other members of the family or village are present to prevent the girl from moving [8]. After infibulation, which describes the narrowing of the vagina by sewing it up, the legs of the girl or woman who has been cut are bound together and she is advised to move as little as possible during the following weeks to allow the wound to heal [8, 9]. The re-infibulation includes the repeated sewing up after cutting the vulva open to allow the woman to give birth [1].

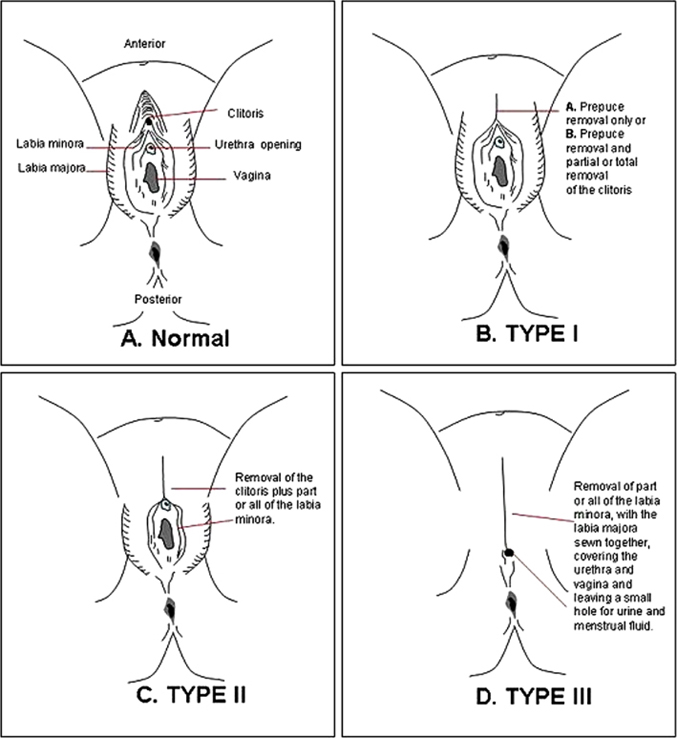

The WHO [2] classifies FGM into four different types depending on the extent of the anatomical changes through the procedure as illustrated in Figure 1.

- (1)

Type I (Clitoridectomy) involves the partial or total removal of the clitoris.

- (2)

Type II (Excision) describes the partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora.

- (3)

Type III (Infibulation) consists in a narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal, which is formed by cutting and repositioning the inner or outer labia, with or without removal of the clitoris.

- (4)

Type IV includes all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, including pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterising the genital area.

It is estimated that 3.3 million girls are at risk of being damaged through FGM worldwide every year [7] and that 90% of FGM cases are Type I or Type II and just 10% include Type III (Yoder et al., 2012 as cited in Ref. 7). FGM is practised in 28 African countries, in some countries in the Middle East and Asia and in some population groups in Central and South America. Available data for several African countries and the Middle East show prevalences ranging from 0.6% (Uganda, 2006) to 97.9% (Somalia, 2006) among women above age 15. However, it should be noted that the prevalence varies greatly between and within different regions (e.g. urban and rural areas) and ethnic groups [10, 11]. Nevertheless, immigrants from all these countries take the practice along to their new countries of residence, e.g., to the USA or Europe (Yoder et al., 2012 as cited in Ref. [7], [11, 12], Moukhyer, as cited in Ref. [13]) (Figure 2).

Source: Map Developed by Children’s Rights and Emergency Relief Organization (UNICEF), 2007. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/fgm-map-big.gif?ua=1

According the WHO [7], FGM has severe negative consequences and no advantages for health and it is estimated that nearly 100–140 million women and girls are suffering from its consequences worldwide. UNFPA [9] has argued that FGM can damage the female body and its natural functions permanently. In addition, as most of the girls and women are cut without either anaesthesia or sterilised instruments, the procedure is very painful and the risk of infections is extremely high. It is estimated that only 18% of the surgeries (FGM) are carried out within health care settings [9].

In addition to the risk of infections, the health risks and consequences are many. Immediate health impacts include severe pain, menstrual and urinary problems, excessive bleeding and septicaemia. The long-term consequences involve infertility, chronic pain, formation of fistula, abscesses and cysts, increased risk of cervical cancer, painful intercourse as well as decreased ability of sexual desire and pleasure. In some cases, death can also occur [1, 14]. There is also evidence that women who undergo FGM and their babies have a higher risk of several obstetric complications like postpartum bleeding, caesarean section, miscarriage or neonatal death. The more severe the type of FGM, the higher is the risk of complications [1, 14, 17]. Nevertheless, the psychological consequences of FGM should not be underestimated. After the procedure the person concerned might suffer from shock, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety and fear of sexual intercourse [14, 15, 16, 17]. The question is, why does the practice still exist despite all the health risks described above and national and international efforts to ban it.

AIM

This literature review aims to explore reasons for the perpetuation of FGM, to identify forces that foster its promotion and persistence and who is responsible for pushing its continuation, in order to understand the underlying factors that make FGM resistant against initiatives and campaigns targeting its elimination.

METHODS

A literature search was performed using the following databases: PubMed, Academic Search Elite, The Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), ATLA Religion Database, CINAHL, EconLit, ERIC, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, SocINDEX and Women’s Studies International. It was complemented by the search in the databases of different international organisations: WHO, UNICEF, United Nations (UN), No Peace Without Justice (NPWJ) and FIDH. The terms searched included: “FGM”, “female genital mutilation”, “female genital cutting” and “female circumcision” combined with “persistence”, “reasons”, “perpetuation” and “tradition”. All sources that approached the topic of FGM were incorporated including literature reviews, systematic reviews, qualitative and quantitative as well as mixed-method studies that described attitudes towards FGM and factors leading to the continuation of the practice. Publications written in English, German, Swedish, Norwegian and French language were included.

The selection process was made by first including material with a relevant title. In a second step, all abstracts were read and examined concerning the content of the literature. In the third selection round full texts of the promising abstracts were read and all appropriate articles and studies that contained relevant information about the perpetuation of FGM were included. In the fourth round, the time frame was set encompassing the years 2010–2014. The 5-year time frame was chosen to ensure that saturation was reached and to have an adequate number of articles concerning the extent of this paper. The time frame was chosen in the last step to focus on the most informative articles and afterwards to decide how many should be included. About 17 articles that fulfilled the inclusion criteria of not being older than 2010 and containing information about the possible reasons for FGM were chosen. Unexpectedly, all review articles included were about studies conducted in Africa. As a result, the title was adjusted to make it clear that the literature review is limited to the African continent (Figure 3).

Adapted from: Schaefer-McDaniel et al. [39].

RESULTS

The underlying causes for the perpetuation of FGM vary between and within countries. But, they are all interconnected to each other and could be found at different levels of the socio-ecological model as illustrated in Figure 4. This model includes factors at the individual, interpersonal, organisational, community and societal level. All these factors at different levels are closely linked to each other and are valued as being equally important. Different factors within one level can interact with each other and also factors at another level to affect health. The socio-ecological model builds on the assumption that no single factor can give an explanation about why FGM still exists and why some girls and women are at higher risk of undergoing FGM than others [18].

Adapted from: Poundstone et al. [40].

At the individual level, a person’s health and religious beliefs, level of education and place of residence affected his/her attitudes towards FGM. For instance, perceived health benefits, low level of education, being a Muslim and living in a rural area positively influence a person’s attitude towards the practice. At the interpersonal level, family and peer pressure had an influence on individual perceptions and acceptance of FGM. At the organisational level, religious institutions and the medicalisation of FGM contributed to the normalisation of the practice. At the community level, social pressure had an influence on a person’s and a family’s views and attitudes towards FGM and affected the decision about whether performing it or not. At the societal level, factors like gender norms and roles, as well as cultural norms and identity had a crucial influence on the performance of FGM.

Individual level

Perceived health benefits and hygiene

According to Tamire and Molla [19], FGM is believed to enhance the overall health status, to ease delivery and facilitate the survival of a newborn. Other authors stated further that FGM is also reported to increase the fertility of a woman (Shell-Duncan, as cited in Ref. [20]) and also to be associated with a “healthier menarche” (Shell-Duncan et al., as cited in Ref. [20], p. 186). Karmaker et al. [21] and Rasheed et al. [22] observed that within contexts where FGM is performed, the practice is not viewed as a dangerous procedure. Berg and Denison [23] pointed out that the general belief of health benefits of FGM is closely associated with hygiene and having clean genitalia as the female genitalia are seen as dirty and in need of being circumcised to become clean. These intra-personal beliefs and perceptions are reflected at the individual level of the socio-ecological model.

Residential area

Another issue at the individual level, is the connection between FGM and the place of residency of a person. According to Rasheed et al. [22], WHO (as cited in Ref. [19]), Cook (as cited in Ref. [19]), Karmaker et al. [21] and Zayed and Ali [20], the prevalence of FGM varies significantly between rural and urban areas. Living in a rural area makes it more likely for women and their daughters to undergo FGM. Their study in Burkina Faso showed a significant association between place of residence and FGM in both mothers and daughters and a U-formed association between economic status and FGM. Women and their daughters coming from middle-income families had a lower risk of undergoing FGM than the richer and poorer participants [21].

Educational level

The educational level of girls also affects their attitudes towards FGM at the individual level. According to Bonessio (as cited in Ref. [24], p. 275), “education level is a major independent factor of change in attitude” in terms of FGM. This statement is supported by the findings of several studies (UN, Klouman; Msuya; Snow, as cited in Ref. [11]). Hearst and Molnar [10] found that the mother’s education has a crucial influence on whether they will allow FGM to be performed on their daughters. Tamine and Molla’s [15, p. 15] study revealed that “daughters from parents with an educational status below high school level were almost two times more likely to be circumcised compared with those whose parental educational levels were high school and/or above, indicating the importance of parental education”. This was also emphasised by UNICEF report, Kandala and Rahlenbeck’s (as cited in Ref. [11]) findings, that showed that the higher the educational level of the mother, the lower the likelihood for them to let their daughters undergo FGM and show support for the perpetuation of the practice.

Afifi et al. (as cited in Ref. [24]) found that women with higher education level who were empowered within their social context were up to 8.06 times more likely to decide not to perform FGM on their daughters. Mudege et al. [25] and Karmaker et al. [21] suggested that the education level of parents was a good predictor for letting their daughters undergo FGM or not. However, while the mother’s level of education was significantly associated with the daughter’s circumcision, the father’s education level was not. The more educated the mother, the less likely was the circumcision of the daughters.

Organisational level

Medicalisation of FGM

According to the WHO [2, p. 3], “local structures of power and authority, such as community leaders, religious leaders, circumcisers, and even some medical personnel can contribute to upholding the practice.” At the organisational/institutional level, medicalisation of FGM, which implies an active role of health care professionals interact with factors at other levels to influence the perpetuation of FGM. According to Pearce and Bewley [26], the medicalisation of FGM implies that the procedure is being performed by a health care provider either within or outside the health care setting. Badawi (as cited in Ref. [20]) reported that it is estimated that about 18% of all FGM procedures are performed by health care professionals. This is the case even when FGM is illegal in the respective country. The incentives for the performance of FGM by health care professional were found to be an additional income, social pressure, belief in the benefits of FGM by itself as well as the advantages of letting it be performed in a medical setting and perceived medical necessity (Badawi, as cited in Ref. [20]).

In a study in the Gambia, up to 42.9% of the health care professionals who participated believed that medicalisation of FGM was a good alternative to the traditional way of performing FGM and that it made FGM safer [27]. The WHO [28] also considered the availability of practitioners especially in rural areas as problem in the fight against FGM.

Religion

According to Khalaf [29, p. 120], “the greatest myth leading to the performance of FGM is religious belief”. Citing Hemmings, Terry and Harris [30] also confirmed the statement that FGM is often believed to be demanded by religion. However, religion studies have shown very different and partly contradictory results. The three religions that are linked to FGM are Islam, Christianity and Judaism.

El-Damanhoury [13, p. 127] stated that “FGM is widely considered to be associated with Islam”. Surprisingly, many Islamic societies that strictly follow the laws of Islam do not practice FGM (Lightfoot-Klein, cited in Ref. [23]; WHO, as cited in Ref. [20]).

Apart from the fact that the practice of FGM is older than the Islam [20], the Qur’an does not contain any laws or mention about performing FGM and can therefore not be a basis for the practice [16, 24]. Gele et al. [31, p. 6] further pointed out that the Qur’an even “clearly rejects any alteration of the human body from the way God created it”. They added that an “important point to note is that Islam safeguards women’s rights to sexual enjoyment and health, and if female circumcision violates those rights, it would automatically be considered forbidden”. But, the question is why many people believe that FGM is demanded by the Islam. Gele et al. [31], Rouzi [12] and the WHO [32] explained this contradiction with the misunderstanding and propagation concerning a quotation of Muhammad where he gave the instruction to a woman who was a female circumciser in pre-Islam times, saying “if you cut do not overdo it because it brings more radiance to the face, and it is more pleasant for the husband” [31, p. 8]. According to Khalaf, religious leaders are very powerful in promoting the continuation of FGM. Gele et al. [31] and Berg and Denison [23] stated that people often believe that FGM is demanded to show their religious devotion and to dignify the Islam. In another study conducted by Gele et al. [31] in Somalia, where religious leaders were interviewed concerning their views on FGM, participants stated that FGM was necessary in terms of religious morality and purity and that these religious aspects prevailed over any kind of problems or complications related to FGM (Momoh, as cited in Ref. [30]).

When it comes to Christianity, El-Damanhoury [13] pointed out that the practice of FGM was already performed before Christian religion became existent. He further stated that the Bible does not contain information about FGM and that Christian laws promoting FGM are inexistent. Christianity faith condemns FGM as a harmful and inhuman practice and the human body is viewed as sacrosanct [33]. Referring to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, El-Damanhoury [13] explained that FGM is also performed in Christian communities, e.g. among groups in Niger, Nigeria, Tanzania and Egypt. These groups believe FGM was demanded by their religion for ensuring the religious aspiration of purity.

Finally, the Refugee Review Tribunal Australia revealed that male circumcision is a requirement in the Hebrew Bible whereas female circumcision is forbidden in Judaism [13]. Furthermore, the Thora does not contain information about the practice of FGM (Werblowsky, as cited in Ref. [29]). Buff (as cited in Ref. [12]) also emphasised that Jewish law forbids any kind of mutilation of the body and thereby also forbids FGM. According to Khalaf [29], the Ethiopian community of the Jewish Falashas is the only known Jewish group worldwide that practices FGM and that this might indicate an underlying cultural tradition and not a religious ritual (Buff, as cited in Ref. [13])

Tamire and Molla [19] stated that despite the fact that FGM has no basis in religion, the majority of people among whom the practice is performed believe that FGM has religious background. The authors referred to other studies (Kitaw et al., Figo Committee, as cited in Ref. [19]) that pointed out that FGM is not a direct outcome of religion, as Judaism, Christianity and Islam all condemn any harm to the body and stressed that FGM is not a part of the sacred scriptures. El-Damanhoury [13, p. 128] concluded that “FGM cannot be justified by any of the three monotheistic religions”.

Community level

Social pressure

At the community/societal level, El-Damanhoury [13, p. 128] stated that “in societies, where FGM is practiced, the social pressure on the families is very high and the necessity to conform to what is considered right may be enough to continue the practice”. According to Berg and Denison [23], only a circumcised girl was seen as an “ideal” girl. As a result, undergoing of FMG was viewed as compulsory and compelled by the community. They further explained that “extensive collective enforcement of the tradition was strongly linked with honour and avoidance of shame, not just for the girl but also the mother and sometimes the extended family” [23, p. 846]. Shell-Duncan et al. [34] noticed that community members who did not let their daughters undergo FGM experienced social pressure by other family and community members, as circumcision of the daughters was viewed as a duty of every responsible parent. These uncut daughters experienced discrimination and stigmatisation from other women’s side and felt shame. Women who are not circumcised will be excluded from common decision making, ceremonies and other community activities. Shell-Duncan et al. [34, p. 1281] stressed that “As insiders, circumcised women cement their belonging in their social network and maximise their social capital by excluding uncircumcised women through harassment and ostracism”. The authors interpreted this as a peer convention.

Yirga et al. [35, p. 52] emphasised that these “social systems are key to families not being isolated. Therefore, some families are forced to practice FGM due to fear of discrimination for deviating from community norms”. Tamire and Molla [19, p. 16] identified in their study culture and stigma as the most common reasons why FGM was being performed. They further clarified that “in addition, the fact that girls themselves demand to be circumcised to avoid shame and stigma is another reason for the continuation of the practice which should be handled carefully.”

The OHCHR (as cited in Ref. [36, p. 151]) concluded that “peer pressure from the community and fear of reducing a girl’s opportunities perpetuate its practice” which makes it difficult to abandon FGM “without detrimentally affecting the social capital of a girl”.

Societal level

Cultural norms/tradition

In the view of Twum-Danso [3, p. 39], FGM is “informed by deeply-rooted socio-cultural ideologies”. Gele et al. [31] added that the motives differ from context to context but are all rooted in tradition and culture. Every community has its own traditions, cultural values and beliefs that influence people’s attitudes towards FGM. These components of a community’s identity are passed on from one generation to another. Twum-Danso [3, p. 39] further claimed that “these cultural values and beliefs are key to the lives of these communities as they guide the way many people live, especially in the way they raise their children”. From the perspective of the community members, this cultural identity needs to be preserved. This statement is approved by the findings from 21 studies reviewed by Berg and Denison [23] who noticed that FGM was perceived as a vital historical tradition which has a high value in the culture, and social systems of the respective study populations and should therefore not be changed. Referring to Hernlund, Twum-Danso [3] explained that there was a common perception that a girl who underwent circumcision showed respect for her cultural and family roots. Berg and Denison [23] and Khalaf [29] pointed out, the girl will also be shown social respect and enjoy a good status as a result. Twum-Danso [3] concluded that according to this view, FGM was not perceived as inhuman or damaging, but rather a tradition that ensured honour for the girl and her whole family. Furthermore, many girls believed that they had no right to refuse getting circumcised and therefore the practice will perpetuate itself. The WHO [2] clarified that a girl who underwent FGM was seen as being raised in a proper way and her dignity was ensured.

Cultural identity

FGM can also be seen as a way to maintain ethnic identity and social unity (Gage and van Rossem; UNICEF, as cited in Ref. [27]). The authors revealed that knowledge and attitudes towards the practice were established by ethnic identity and attitudes towards FGM varied between different ethnic groups [27]. In this sense, according to Shweder (as cited in Ref. [25]) and Karmaker et al. [21], belonging to a certain ethnic group can be a good predictor of FGM practice. Hemmings (as cited in Ref. [30 p. 43]) explained that FGM is “an element of tradition and therefore maintains cultural identity” and that denial of getting circumcised would be perceived as an insult to the older generations and their dignity. According to Kaplan et al. [27], this ethnic and social identity is especially important for members of smaller communities.

Gender norms and roles

Aesthetics

Khalaf [29] and Pearce and Bewley [26] stated in their papers that FGM is also performed in order to enhance the beauty of the external female genitalia and thereby the whole body. The authors emphasised that the female genitalia are often not only seen as unclean but also as imperfect and ugly. Khalaf [29] and the WHO [2] also pointed out that in some communities the vagina is seen as a harmful organ that is so similar to male genitalia that the external parts need to be removed so that a woman becomes a real female.

Transition to womanhood

FGM is also perceived as an inevitable part of becoming a woman and getting female identity and being introduced to the social network of strong women [23]. Gele et al. [31] added that FGM could be seen as the physical evidence of the traditional rite of passage from girlhood to womanhood that confirmed gender identity through the idea of enhanced femininity. It also assures that the girl has received all knowledge that makes her worthy being incorporated in the female adult community. It is viewed as an inevitable part of confirming and protecting femininity (Gage and van Rossem; UNICEF, as cited in Ref. [27]) and as something “essential in the distinction between sexes as necessary opposites in the community” [27, p. 2].

Sexual morals

Findings from Berg and Denison [23] stressed that sexual morals also represented a prime reason for the perpetuation of FGM because it is seen as the basis of moral virtue and a proof of a woman’s morality. According to Yirga et al. (as cited in Ref. [11]), a woman that had undergone FGM is considered to be less likely to be promiscuous, sexually active or even sexually hyperactive and easier to control by their husband acting with proper sexual behaviour. Morison et al. (as cited in Ref. [30]) interviewed women about reasons for undergoing FGM. The answer was that FGM was conducted to control their sexuality. They reported that they had severe pain during sex or that they were even unable to have sexual intercourse at all.

The WHO [28] identified a very negative view on female sexuality as embodied by the female external genitalia. In contrast, Jirovsky [37] found in her study in Burkina Faso that female sexuality was seen as natural and rather complementary to male sexuality than something negative. But as women were also viewed as being too active sexually, there was a need to control their sexuality through FGM in order to adapt it to what is perceived as a morally proper behaviour [37]. The WHO (as cited in Ref. [29]) stated further that it is often believed that female sexuality needs to be controlled by FGM to enhance the sexual enjoyment of men and to decrease the excessive female libido. In a study conducted by Hassanin and Shabaan [24], the mothers who participated stated that one reason for letting their daughters get circumcised was to reduce their sexual desire. A daughter losing her virginity before marriage would bring shame to the whole family and must therefore be prevented by all available means.

Marriageability

The WHO [28] stated that entering marriage as a virgin guaranteed the family the protection of their ethnic groups’ reproduction. Comparing 21 studies, Berg and Denison [23] showed that marriage was a vital determinant for getting circumcised and that many men had a preference for a circumcised wife. However, in this context marriageability was closely linked to sexual morals. Chastity before marriage was viewed as a predictor for fidelity in marriage and evidence for morality, virginity, purity and modesty. Being a virgin at marriage ensures the whole family’s honour. Being cut during childhood or teenage is believed to be an important requirement for a good and honourable future marriage. Not being circumcised could lead to rejection of marriage. Hearst and Molnar [11, p. 621] presumed that “in culture in which marriage may be the only avenue for a woman’s financial security, a family may feel that FGC is important to ensure a safe and secure future for their daughter”. Shell-Duncan et al. [34] also added that as soon FGM becomes a necessary requirement for marriage the practice is locked in the community and social context.

Male preference

In two studies reviewed by Berg and Denison [23], it was found that men preferred women who were circumcised based on the belief that they will have better sexual enjoyment. Gele et al.’s [31] study in Somalia also showed that up to 96% of the men who participated had a preference for marrying circumcised women, whereas just 2.8% of the male respondents stated they might consider marrying a woman who did not undergo FGM. In addition, women believed that FGM only increased the sexual pleasure of men because of the narrowed vagina and that is why men preferred circumcised women. Other research (Johansen and Johnsdotter, cited in Ref. [23]) found that men’s preference of having a circumcised partner is strongly related to chastity and honour, and less connected to an increased sexual enjoyment. A study conducted in Egypt suggested that men viewed FGM as a mean for keeping their wives faithful. They did not worry about the impact of the procedure on the women’s sexual pleasure, but only on their own sexual enjoyment, which they considered as a vital aspect of happiness in marriage (United Nations Development Programme [UNDP]; UNFPA; WHO, as cited in Ref. [38]).

Conversely, a study conducted by Hemmings (as cited in Ref. [30]) found that there are huge disparities between what women assumed to be men’s view on FGM and what was their actual view. The women in Hemmings’ study were sure about men demanding and supporting FGM, whereas many men did not support the circumcision of their daughters.

Patriarchal structures and gender inequity

Shell-Duncan et al. [34, p. 1281] declared that the “female circumcision serves as a signal that girls have been taught the art of subordination to their future husband, husband’s brothers, and most importantly, to their mothers in-law”. Gele et al. [31, p. 2] added that “the practice reflects a gender inequality that establishes an extreme form of female discrimination”. Kaplan et al. [27] pointed out that a strong gender identity does not automatically imply gender equity and that the suppression of the female members of a patriarchal society is a main reason for the perpetuation of FGM. Edouard et al. [36, p. 151] concluded that the continuation of FGM mirrored the powerful convincing role of the social order in maintaining gender inequality.

DISCUSSION

The results of this review show ambiguous and complex reasons behind the perpetuation of FGM.

At the individual level, the reasons for undergoing FGM are both medical and aesthetics. However, apart from people’s own beliefs and perceptions, no scientific evidence was found to support the perceived health benefits [7]. The latter may explain why many studies included in this review reported that FGM was not perceived as dangerous among participants despite the alarming health consequences it caused. Linking FGM to beauty might be an expression of social pressure and the individual need to fit in with their community views about what is beautiful. One important factor that predisposed a girl to undergo FGM, was place of residence. The chance of undergoing it varied depending on whether the girl resided in an urban or rural area. Living in a rural area was associated with an increased likelihood for girls and women to be circumcised compared to girls and women with a residence in an urban area. Karmaker et al. [21] supported this view with their findings. This increased likelihood of undergoing FGM can be explained by very little or lack of contact with the outside world reducing their chances to new influences and ideas that might change their way of looking at this practice. Moreover, maybe at the rural area, customs and traditions are more respected than regulations and laws.

At the institutional level, the involvement of health care professionals in the practice of FGM can legitimate it and make it look harmless. However, although an increasing number of FGM procedures are performed in health care settings, most girls and women are still cut in traditional ways by a local exciser [8, 9]. This fact was also emphasised by Pearce and Bewley [26] who reported that only 18% of the circumcisions were performed by health care professionals. The fact that health care professionals are willing to perform FGM against their medical code and the laws concerning a ban of FGM in their respective countries, can have an important influence on the continuation of the practice.

In the socio-ecological model, we can find religion at the organisational level as an institution but also at the individual level as an individual belief. It even interacts with cultural factors at other levels (e.g. tradition, education) to impact on the performance of FGM. One of the most important findings of this review is that although people in most of the settings where FGM is practised are referring to religion as the underlying reason for performing or undergoing FGM, none of the studies reviewed showed evidence of any of the three religions mentioned (Islam, Christianity or Judaism) being connected to FGM. The Holy Scriptures of these religions do not contain any recommendation about the performance of FGM [20]. Furthermore, all three religions forbid any harmful practice to the body [12, 13, 29]. Moreover, FGM is prevalent in only one Jewish ethnic group and some Christian ethnicities, but very common among followers of the Islam. But concerning the Islam, a misinterpretation of one Hadith in the Qur’an seems to be the underlying cause for a pervasive perceived duty to undergo FGM for honouring the Islam [31]. Curiously, FGM seems to be practiced by followers of all three religions particularly in Africa but rarely outside this continent. Consequently, it can be assumed that at some point in history culture must have been mixed with religion resulting in the belief that FGM is required by religion. As a result, it seems reasonable that the culture of a community is more influential in the performance of FGM than religion itself.

Another very important aspect in the perpetuation of FGM is education. Educational level and FGM prevalence rate were strongly connected in most of the reviewed studies. A mother’s level of education had a crucial influence on her willingness to let her daughters undergo FGM or not. The father’s educational level did not appear to have the same impact on the daughter’s FGM prevalence rate [25]. Moreover, the fact that mothers with a lower education level are more likely to circumcise their daughters closes the vicious circle of FGM, as the girls who do not receive a proper education will be future mothers who then again will let their daughters undergo FGM.

However, it was unclear whether it is men or women who are the driving forces behind the perpetuation of FGM. But, the role of male community and religious leaders as well as women themselves cannot be underestimated. On the one hand, it was argued that FGM commonly occurs in patriarchal societies, although it is not performed in all patriarchal societies [27]. On the other hand, it was often stated that women are the strongest perpetuators of FGM [27, 34]. But, it should be noted, that despite strong evidence for women being the driving forces behind FGM in many contexts, in the background of these societies it is men who are the rule makers as husbands, community and religious leaders. Moreover, much of the research being done focused on women’s attitudes and perceptions about FGM and very little is known about men’s attitudes. Further studies need to explore the men’s role regarding FGM before being able to give a whole picture of the gender roles concerning the practice.

CONCLUSION

The underlying reasons for the performance of FGM vary between and within countries. But in each setting, there was always more than one reason for the perpetuation of FGM. These included intra-personal reasons like hygiene, aesthetics and perceived benefits for health, which were firmly related to the perpetuation of the practice. Additionally, demographic factors like place of residency and educational level of parents and girls were strongly linked to FGM. The medicalisation of FGM at the institutional level also contributes to some extent to the continuation of the practice. But, contrary to widely held beliefs, no evidence was found about religious requirements about FGM although the practice in many cases is performed out of perceived religious demand. The most important factors behind the perpetuation of FGM were culture and level of education. Cultural beliefs and traditions are very complex and often built on gender inequality. To develop successful interventions, it is important to understand what factors make a girl more likely to be circumcised. Being a young girl, coming from a small community in a rural area in Africa, being Muslim and having low education or parents with low educational level increased the likelihood to undergo FGM. As legal issues and campaigns aiming to eradicate the practice showed a limited effectiveness, it is crucial to find a way to tackle FGM which keeps a balance between respect of culture and human rights. It is also vital to involve practicing communities in every step, from development to the implementation of a programme so that abandonment of FGM becomes a joint decision. Although it is unclear whether it is men or women who support the continuation of FGM, education and the empowerment of women seem to be the fundamental steps to decrease gender inequality and thereby combat FGM. Future actions should take into account all these aspects to encourage or persuade people to abandon the practice of FGM. These actions should target the young generations, both girls and boys with adequate education including all aspects of FGM and gender inequality. If future mothers and fathers understand why FGM occurs and are knowledgeable about its negative impacts they might be willing to find ways to abandon the practice.