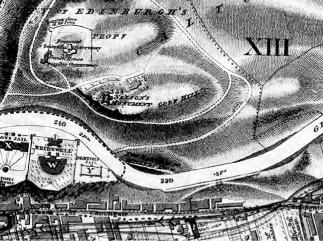

Plate 1 Detail from Kirkwood’s Plans and Illustrations of the City of Edinburgh Section 5 (1817), showing the location of Herman Lyon’s burial plot.

Crown copyright Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS).

The Referendum on Scottish independence in September 2014 and the sweeping gains made by the Scottish National Party in the General Election in May 2015 provided pause for thought about the relationship between the Jewish communities that live in the five territories that make up the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. On the level of semantics, we must now studiously avoid using the term “Anglo”-Jewry with reference to British Jewry because the pundits consider it outdated.1 Popular usage of the term Anglo-Jewry persists, as a glance at the Wikipedia entry on “British Jews” shows. (I leave aside the whole debate about the reality of the “Jewish community” as opposed to a series of “communities” as beyond the scope of this investigation.) American Jews also use the term “Anglo-Jewish” to refer to themselves in the sense of “English-speaking”, while Jews from English-speaking countries who have settled in Israel call themselves “Anglos” or even “Anglo-Saxim”. Perhaps “British” Jewry should also be avoided, not least because it no longer includes “Irish” Jewry, that is the Jewish community living south of the Republican border. Political relationships have changed in the past and may do so again in the future. Nevertheless, in terms of their physical legacy, Jewish communities living within the geographical orbit of the British Isles are inextricably linked. The patterns of settlement and the building of communal infrastructure are closely similar. The establishment of burial grounds and the building of synagogues follow much the same patterns in England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. Indeed, preliminary research demonstrates similar patterns in other parts of the English-speaking world where Jewish communities have thrived under British Imperial rule: for example, in Jamaica,2 which led the way in granting civil and political emancipation in 1831, ahead of the motherland (1858); in Barbados, Canada, South Africa,3 and Australia.

In terms of architectural form and style, synagogues in Britain and throughout the Empire generally followed European fashions during the Victorian era that was characterised by the “Battle of the Styles”. Regional differences only occurred in the choice of which Revival style was deemed most appropriate within the local context. This was usually determined by the dominant religion. I have explored elsewhere4 how the Gothic Revival was eschewed for synagogues in England because of the strong association, courtesy of Pugin, with Christianity, and especially with the High Anglican Church. In Ireland and Wales this was not the case: synagogues were built in neo-Gothic style in areas where Catholicism and Welsh chapel culture were strong.5 Everywhere, Gothic Revival was deemed acceptable for ohalim (prayer halls or chapels) in Jewish burial grounds, especially where these were plots in public cemeteries that employed the local Christian city surveyor or municipal architect to design the chapel buildings for all “denominations”.

The present paper draws together my previous research6 and further explores the communal architectural heritage of Scottish Jewry, consisting of funerary architecture, mikvaot (ritual baths), and purpose-built synagogues. It concludes with a few thoughts about the future of this heritage, a significant testimony to the place of a minority within a minority culture.

Jewish burial grounds and funerary architecture in Scotland

The heritage of Scottish Jewry dates back to the early nineteenth century and is concentrated in the “two capitals” of Edinburgh and Glasgow.7 The pattern of Jewish settlement, as Cecil Roth once observed, typically involves the acquisition of a burial ground before the opening of a purpose-built synagogue. In many cases, the synagogue disappears but the cemetery, as a sacred place in perpetuity, remains. This is certainly true in Scotland where surviving burial grounds predate known synagogue buildings.

The formation of an organized Jewish community in Edinburgh is usually dated from 1816, making it the oldest in Scotland, when a synagogue was opened in a house in Nicolson Street. However, as else where, there was a prehistory of Jewish settlement in Edinburgh which, by the end of the eighteenth century, was already reputed to be the “Athens of the North”. Individual Jews settled in Edinburgh, some attracted by the reputation of the University in the medical sciences.8 One such was the German-born Herman Lyon, also known as Heyman Lion, who practised as a dentist and “corner operator”, Georgian English for a “chiropodist”. He was the author of a learned treatise on the corn published in 1802, in all probability of doubtful scientific value. However, in the mid-1790s, he was sufficiently successful to purchase, for 17 guineas, a private burial plot for himself and his wife on Calton Hill overlooking the city.9 Lyon’s was a remarkable transaction, taking place between the City Council and a registered alien in the middle of the French Wars. This was in the period just before Calton Hill became the imposing landmark it is today, dotted with eccentric structures, ranging from Gothick to Greek Revival. Most of the monuments on the hill were erected during the Napoleonic Wars down to 1830. The actual necropolis lies across Waterloo Place and contains some interesting memorials dating from the mid-eighteenth century.

The “Burying place of the Jews” is clearly marked on Kirkwood’s Plans and Illustrations of the City of Edinburgh Section 5 (1817; plate 1).10 It is also shown on the Ordnance Survey Edinburgh map of 1851, published in 1852, labelled “Jews’ Burial Vault (Lyon’s Family)”. The small site was enclosed with a wall at Lyon’s expense. It is believed that only the dentist and his wife were buried there, probably in 1795. Today, all that remains are a few rubble stones. According to testimony dating from the 1930s, quoted by Abel Phillips, the historian of Edinburgh Jewry, it seems that the City Council demolished the vault in the 1920s and that the remains were transferred to Braid Place, the first Jewish communal cemetery in Scotland, which was opened in 1820.11 However, there is no evidence, material or documentary, on which to base this contention, although it is known that descendants of the Lyon/Lion family were interred at Braid Place.

The tiny Jewish burial ground in Braid Place, also known as Sciennes House Place, Causewayside, measures a mere 1/24th of an acre (1815 square feet) in size. It was in use until 1867 when a larger ground was opened at Echo Bank, to which I shall return later. Braid Place was taken into the care of Edinburgh City Council in the early 1990s. Unfortunately, no burial registers have survived, having apparently been destroyed by a private developer. Earlier surveys identified a total of twenty-nine inscriptions. The oldest originally recorded by the Survey of the Jewish Built Heritage (SJBH) in the UK and Ireland (in August 1999) was entirely in Hebrew and seemed to refer to one Moses, son of Abraham Mazlo, of the “holy communit[ies]” of Birmingham and Edinburgh who died on Shabbat and was buried on Sunday 3 Tammuz 5585 (19 June 1825). Several stones have ornate carved heads, one in particular with a scroll, a lion-head in profile, and a winged figure with sickle (probably representing the Angel of Death) carved in relief. Representation of the human form is rare in Jewish funerary art, especially in relief, but is not unknown, as can be seen in the most famous Jewish cemetery of all, in Prague.12

Around Britain, quite a large number of Jewish burial plots, especially in provincial towns, are to be found within the boundaries of municipal cemeteries, a phenomenon which dates back to the beginnings of publicly funded provision of city cemeteries in the 1850s. Scotland is no exception. Indeed, the earliest example of a Jewish plot planned and landscaped as part of the overall design of a public cemetery is the Jews’ Enclosure at the Glasgow Necropolis.13 The Glasgow Necropolis was laid out in 1829–33 on the model of the prestigious Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris. In 1830 the Glasgow Jewish community paid a hundred guineas outright to secure provision in what was one of the first public cemeteries in Britain. In fact, the earliest burial in the entire cemetery was that of Joseph Levi, aged sixty-two, a quill merchant, who was interred on 12 September 1832 in the Jewish plot.14 The rest of the cemetery did not become operational until May 1833. Levi had died of cholera, an epidemic raging in the city at the time. His coffin was filled with lime and water, either to prevent the spread of infection or as protection against grave robbers.

The tiny Jews’ Enclosure, in use from 1832 to 1851, was provided with a stone boundary wall, monumental column, and iron gateway erected around 1835–6 at the expense of the city. Its column and gateway were designed by John Bryce (1805/6–1851), who was responsible for other contemporary monuments within the complex including the Catacombs and the Egyptian vaults. Bryce’s obelisk15 was supposedly modelled on Absalom’s Pillar in Jerusalem. However, as George Blair commented in 1857, the conical-shaped dome over that rock-hewn tomb actually looks nothing like its classical “counterpart” in Glasgow.16 It may be relevant that the famous Scottish traveller-artist David Roberts’s Holy Land, which was published in 1842, included a view of Absalom’s Pillar. This could well be the origin of the connection made in Scotland between the two monuments. Nevertheless, the combination of Byronic and biblical quotations inscribed on the column and gateposts, now gently crumbling away (due for conservation by the city council in 2015), must rate the Jews’ Enclosure in the Glasgow Necropolis as one of the most romantic Jewish sites in Britain.

Today, there are a total of nine Jewish cemeteries in Glasgow. The Jews’ Enclosure in the original city necropolis was followed by several other Jewish plots in vast Victorian cemeteries that were laid out during their heyday in nineteenth-century Glasgow. The first of these was in the Eastern Necropolis (1847), known as Janefield and more recently as “Gallowgate”, where the Jewish plot lies peacefully in the looming shadow of Celtic football ground. However, when the land was purchased in 1853 by Glasgow Hebrew Congregation (then based at Howard Street), the vendors were the privately owned Eastern Necropolis Company, rather than the city council. The first burial took place in 1856.17

Thirty years later a Jewish section was opened on the southern side of the Western Necropolis in Maryhill coinciding with the opening of the whole cemetery (1882).18 The initiators were an immigrant congregation from the Gorbals on Glasgow’s South Side, the Scottish equivalent of the East End of London. The founding Gorbals congregation was not formally constituted as the Chevrah Kadisha Synagogue until 1889. It was afterwards known as “Buchan Street” after the old Baptist church at 33 Buchan Street (corner of Oxford Street) that was used for worship from 1897 or 1899 to 1972. However, in 1895, the established Glasgow Hebrew Congregation, better known as Garnethill Synagogue (on which more later) in Glasgow’s West End, stepped in to rescue the burial ground because the impoverished Chevrah Kadisha Synagogue had apparently failed to complete the purchase from the Western Necropolis Company. Garnethill also purchased its own land on the other (eastern) side of what became the central pathway. (The disused red-brick ohel was built by the short-lived [Glasgow] United Synagogue [1898–1906]. This cemetery was afterwards shared with the Poalei Tsedek hevrah (or society) of 11 Oxford Street and, from 1929, with the Beth HaMedrash HaGadol, known as the New Central Synagogue, Rutherglen Road [1925–56]). This was not merely a philanthropic gesture, but also a bid to fend off competition from immigrant congregations offering cheaper burials.19

Perhaps the most poignant Jewish section in Glasgow is found in the Craigton Cemetery.20 It was purchased from the Craigton Cemetery Company by the very first hevrah established on the South Side, at Commerce Street. The first interment took place in 1881, some eight years after the opening of the cemetery (1873). Of some 240 recorded burials,21 the vast majority of which were of infants or children, today hardly a memorial stands. In all likelihood there had never been many tombstones, the bereaved being too poor to afford them. By 2014 the condition of this cemetery had vastly improved, but the Jewish section had all but disappeared under a jungle of brambles. Even the grey granite obelisk for Marcus Cohen, the last person to be buried in the plot in 1908, had collapsed into several pieces. There was no sign of the spiked iron railing that once separated the consecrated Jewish plot (located by the eastern boundary with Crosslee Street) from the rest of the cemetery. Intervention by Jewish Heritage UK secured the restoration of this monument and the tidying-up of the remains of the plot by Glasgow City Council.

Craigton was one of the last cemeteries in Glasgow to pass out of the hands of a private cemetery company into the control of the city council, in about 2006 (when first visited by SJBH in 1999, the whole cemetery was completely overgrown and we were unable to locate the Jewish section). The setting up of private cemetery companies was far more widespread in Scotland than in England during the nineteenth century, but they tended to go out of business once all their clients had died. The business model was simply not sustainable; commercial cemetery companies went bankrupt when all their plots had been sold and filled. Consequently, their cemeteries frequently fell into decrepitude, unless rescued and restored by city and district councils.

In the twentieth century the Glasgow Jewish community purchased private land contiguous with large public cemeteries. This is the case for Riddrie Jewish Cemetery that today, thanks to the complete disappearance of its boundary wall, looks merely like a Jewish section at the westernmost corner of the Riddrie Park Cemetery, which was opened in 1901. In fact, the Jewish cemetery was acquired and consecrated separately a few years later, in 1909.22 It originally had its own gate on Provenmill Road, but must now be approached via the main gate on Cumbernauld Road. The purchasers were the now defunct South Portland Street Synagogue, the largest synagogue on the South Side (on which more later) and responsibility eventually devolved on the Glasgow Hebrew Burial Society (see later). Like other grim inner-city cemeteries in Glasgow, Riddrie has suffered badly from vandalism in the past. However, in recent years, the city council has invested in cemetery maintenance so that the appearance of large sites like Riddrie, the Western Necropolis, and Craigton has considerably improved. (Unstable tombstones in the Jewish plot at Riddrie have been laid flat by the council.)

Sandymount Jewish Cemetery dates back to 1905,23 predating the establishment of the Glasgow Hebrew Burial Society, a mutual aid society funded by weekly subscriptions, by nearly three years (1908). The earliest burial listed in the registers kept at Glenduffhill by Glasgow Hebrew Burial Society (inspected by SJBH in 1999) was that of baby Bessie Chitterer (d. aged 8 months, 11 January, buried 12 January 1908). The oldest stone found on site in 1999 was that of Lazarus Fell (d. aged 44, 22 January 1908); it had toppled over. Contiguous with the general Sandymount Cemetery (1878), the Jewish plot had been acquired by the Poalei Tsedek hevrah, which became a founder member of the Burial Society. The site has been undergoing restoration by the Sandymount Regeneration Trust, set up in 2004. An even larger, densely packed Jewish cemetery, contiguous with the public Glenduffhill Cemetery, was opened as the successor to Sandymount in 1933.24 It boasts a bunker-like two-storey ohel-cum-bet taharah (or mortuary; 1933–4) with caretaker’s house above that faces onto the street. Over the municipal border in Renfrewshire is Cathcart Jewish Cemetery, at the corner of Cathcart Cemetery.25 This ground is the one most in use today by Glasgow’s Orthodox community. It was opened by Queen’s Park Synagogue (on which see later) in 1927.

Plate 2 The Jewish section at Newington Cemetery, Edinburgh, known as Echo Bank (1867–9). Photograph Andrew Petersen for SJBH.

Finally, in the same area of Govan (on the South Side) as Craigton, Cardonald Cemetery, Mosspark Boulevard, hosts the only Reform Jewish plot in Scotland, created in 1952 for Glasgow New Synagogue that had been established in 1932,26 one of only a handful of Reform or Liberal congregations founded outside London before the Second World War. (In 1969 the Reform congregation moved to its fourth home, a former Church of Scotland parish hall at 147 Ayr Road, G77, which is situated behind the Orthodox Newton Mearns Synagogue. This parish hall was converted into a synagogue to seat three hundred, plus three classrooms. The outline of the cross in the gable is still visible beneath the current Magen David (plate 11).27) As elsewhere, the Glasgow Hebrew Burial Society refused to conduct funerals of members of the Reform synagogue whose halakhic status was questionable (Jewish status is transmitted through the maternal line or may be acquired through conversion al pi halakhah – according to [Orthodox] Jewish law). The Reform initially turned to the Craigton Cemetery Company for assistance.28 Neatly kept with traditional matsevot, the Reform plot in the municipal cemetery at Cardonald has its own ohel finished in undistinguished roughcast (harling) and sporting a prominent Magen David on its front gable.

Over in Edinburgh, Braid Place’s two successors were originally located in commercially run cemeteries owned by private companies. Newington Cemetery, referred to locally as Echo Bank, was founded in 1846 and a corner was sold to the Jewish community in 1867 (plate 2). The first identifiable Jewish entry to appear in the general registers (kept by Edinburgh City Council at nearby Mortonhall Crematorium) is that of Saul Samuel (d. aged 70, 6 March, interred 8 March 1869).29 Of special interest here to literary buffs are a number of stones in memory of the Spark and Camberg families that were restored in the 1990s by Robin Spark, the son of the novelist Muriel Spark (1918–2006). Much to the embarrassment of his Catholic-convert mother, he rediscovered his Jewish roots and joined the Edinburgh Hebrew Congregation.

Currently in use, Piershill30 is the youngest and largest of the Orthodox Jewish cemeteries in Edinburgh.31 It is the only Jewish cemetery left in Scotland that is still privately owned, by the Edinburgh Eastern Cemetery Company, so private in fact that access to the burial records has not in the past been easy to achieve. This site is a good illustration of the challenges posed in establishing precise dating for burial grounds in the apparent absence of a complete documentary record. The company holds general registers dating from the opening of the cemetery in 1883, but their Jewish records, kept in a separate register, appear to go back only to 1938. This compares with registers from 1923 found in a cupboard by the Edinburgh Jewish Burial Society (the year in which the combined ohel and bet taharah was opened in a new extension to the north). The earliest Jewish tombstone on site dates from 189232 but, according to a field survey carried out in the 1970s, the first burial actually took place two years earlier, in 1890.

Vestiges of past Jewish life elsewhere in Scotland are mainly found in municipal cemeteries. Jewish communities in Scotland, outside Edinburgh and Glasgow, were not generally large enough to sustain a private burial ground, let alone a purpose-built synagogue. Rooms in dwelling houses or buildings converted from other uses, such as offices and warehouses, and sometimes churches, served for Jewish worship, a pattern emulated throughout Britain and in big cities everywhere in which Jewish immigrants settled.

West of Glasgow, Greenock in the 1890s was for most immigrants a stopover on the route from the Baltic to New York. A synagogue was opened in 1894 and a cemetery next door on Cathcart Street. The synagogue and cemetery were bombed during the Second World War, and postwar burials were sent to Glasgow. All that remains is a row of seven Jewish tombstones in the town’s historic Bow Road Cemetery (1846). The earliest is dated 1911 and the most recent 1945.33

The small Jewish section at the north-western34 edge of Dundee’s Eastern Cemetery, Arbroath Road, was purchased in 1888 and the first burial took place the following year.35 The Dundee Burial Board charged “the lowest rate, 15s 6d [c. 77p], a lair (or £48 15s. in all) [for 50 grave spaces], this sum being fixed in consequence of representations made as to the smallness of the funds at the disposal of the congregation.”36 The ground was to be surrounded by a wooden fence with a gate. From the 1880s the congregation worshipped in a house in Ward Road. In 1919 they moved to a converted warehouse at 15 Meadow Street (now Meadow Lane),37 down by the docks. It was demolished in 1972 when a purpose-built synagogue was erected (about which more presently).

The Jewish community in the “Granite city” of Aberdeen dates back to 1893, with a previous synagogue in Marischal Street opposite Trinity Quay. Since 1945 they have worshipped in a converted terraced stone house at 74 Dee Street. The Jewish section of the Grove Cemetery, at Persley (1898), dates from 1911.38 At that time, the cemetery was still owned by a private company but it is now in the care of Aberdeen City Council.

Inverness remains the most northerly point of organized Jewish settlement in Scotland, indeed the most northerly place visited by the Survey of the Jewish Built Heritage. Inverness’s tiny community, in common with Dundee and Aberdeen, was a product of the late Victorian period. Burials were taken to Glasgow, more than two hundred miles away, until early in 1906 when the death of a boy aged fourteen, newly arrived from Russia, prompted the community to secure a plot in the town cemetery.39 Indeed, the earliest inscription, entirely in Hebrew, in the small Jewish section of Tomnahurich Cemetery, is for a boy called Haim Tzvi, and the date on his stone, 6 Tevet 5666, corresponds with the civil date 4 January 1906 cited in the municipal burial registers. The section contains approximately twenty-three plots and is still in use from time to time, although there is today no Jewish community in the town. Jewish communities once existed also in Falkirk, Dunfermline, and Ayr, but left no material heritage behind them at all.

Scottish synagogue architecture in the Victorian period

Garnethill, the “cathedral synagogue” of Glasgow Jewry, was opened in 1879. It was the first purpose-built synagogue in Scotland. The Glasgow community had been founded in 1823, making it junior to Edinburgh by seven years. Garnethill replaced a converted apartment building on the corner of George Street and John Street that had served as a synagogue since the 1850s. One stained-glass fanlight bearing the date “AM 5619” (=1858/9) was removed to Garnethill and survives over the choir in the west gallery facing the Ark.

The construction of Garnethill on a steep site overlooking the city centre (located just round the corner from Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Glasgow School of Art, 1907–8) was a major undertaking for Glasgow’s community, which at the time numbered fewer than a thousand. The sloping site provided scope for an extensive semi-basement floor that originally accommodated a mikveh (it fell out of use, was converted into a boiler room, and was replaced in the 1880s by facilities on the South Side). This replaced an earlier facility built at George Street, the first mikveh in the city and which had been enlarged in 1867. Garnethill’s basement, typical of many large Victorian synagogues, also contained classrooms, a caretaker’s flat, two committee rooms, and a large communal hall. From the outset, Garnethill was the Englischer Shul of Glasgow that expressed in bricks and mortar the growing security of a Jewish community that had found its feet and was prospering in the major industrial city north of the border. The final bill for the erection of the new synagogue that sat some 550 worshippers was almost £14,000, including the cost of the site. The mortgage had not been paid off fifty years later.

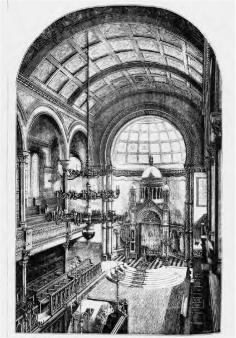

The awkward shape of the plot dictated a variant L-shaped plan with the Ark apse at the east and the main entrance at the north (Hill Street), through an imposing double-height, arched yellow-stone portal with several orders. However, the interior plan of Garnethill was typical of the grand “cathedral synagogues” built in the high Victorian period.40 From the main portal, a spacious entrance hall and an additional long vestibule extend the length of the prayer hall. A grand staircase divides at the landing into two parallel flights, lit by three glorious stained-glass windows filled with floral-patterned panels in vivid jewel colours. The main prayer hall is almost a basilica, as in a cathedral, that is, with the “nave” separated from the aisles by arcades carrying the women’s gallery that extends round three sides (plate 4). However, there is no clerestory. The deep rear west gallery contains the choir loft. The pulpit (of slightly later date) is a dominating feature, placed in the centre of the Ark platform. It projects into the main space on a set of semi-circular marble steps.

Stylistically, Garnethill is predominantly Romanesque Revival both outside and in. This was one of the styles considered most suitable for synagogues in Victorian Britain.41 The main doorway’s arch is of several orders with a large rose window above. Inside, the ceiling of the prayer hall is a deep, simply coffered barrel vault carried on round arcades. The gallery fronts are of gilded wrought iron and are elegantly bellied. The polygonal apse is filled with panels of black, yellow, and frosted stained glass. A similar glass roof had been employed at Brighton’s Middle Street Synagogue a few years earlier,42 but skylights are, in any case, a characteristic feature of Glasgow buildings, designed to admit maximum light in a northern city. The skylight and many other features of Garnethill were repeated in a watered-down version at Queen’s Park Synagogue in the 1920s.43

Garnethill is an excellent example of the stylistic eclecticism typical of nineteenth-century synagogue architecture all over Europe. It was described at the time both as “Romanesque” and “Byzantine” (plate 3). Low-key orientalizing features are discernible on the façade, notably the pair of “horned” turrets, the keyhole window in the pediment, and the expansive lobed arch over the entrance, whose gentle curve hints subtly at a Moorish horseshoe. However, the fashion for Orientalism in synagogue architecture, which reached Britain from the Continent during the 1870s, tended to find its fullest expression away from public gaze.44 British inhibition precluded much show of exoticism. However, once you enter Garnethill, the entrance hall, vestibule and floor of the prayer hall are richly laid with multi-coloured Minton floor tiles in a repeating diamond pattern containing six-pointed stars (restored in 2008 by Page/Park Architects with assistance from the Heritage Lottery Fund). The ceilings are of decorative stucco with an ornate and colourful cusped archway between, which is almost Indian in appearance.

Enter the prayer hall and the slender iron columns to the arcades of the gallery have Byzantine cushion capitals. The pulpit features inlaid marbles with horseshoe arcades and Magen David motifs. The timber Ark is gilded, domed, and turreted. It stands in an apse, flanked by arcades, within a large horseshoe arch borne on clustered columns with basket capitals. Garnethill’s Ark is comparable with those at Princes Road in Liverpool (1872–4) and its younger sister building in London, the New West End Synagogue, Bayswater (1877–9). Both of these Grade I Listed synagogues were largely designed by the Scottish-born architect George Audsley, the latter in association with Nathan Solomon Joseph (1834–1909), who served as architect to the United Synagogue in London and was the Chief Rabbi’s brother-in-law. Joseph was the champion of the use of Oriental style in British synagogue architecture. Indeed, Garnethill opened in the same year as St Petersburgh Place (1879). Joseph worked on both projects at the same time, in Glasgow acting as consultant to the local architect, John McLeod (1838–1888) of Hope Street.45 McLeod was the son of a Dumbarton shipbuilder and an elder in the Scots Presbyterian Kirk. He designed a number of churches, but had never before tackled a synagogue. So Joseph was again brought in to assist. Garnethill’s builders were J. B. Bennett & Sons of Gordon Street, Glasgow, to whom Buildings of Scotland also ascribed the outstanding stained glass.46 Engravings of the synagogue appeared in The Builder in 1881 (plate 4).47

Plate 4 Garnethill Synagogue, Glasgow, engraving of the interior,

The Builder, 5 March 1881. Courtesy Bob Skingle. Copyright Historic England.

Almost as soon as it opened, the Englischer Shul at Garnethill was shunned by the growing Yiddish-speaking immigrant community, centred on the industrial Gorbals on the South Side of the River Clyde, where a similar pattern of hevros and shtieblekh in converted houses, workshops, churches, and chapels developed, as in other conurbations, pre-eminently in the East End of London. Not only was Garnethill, as its name suggests, located at the top of a steep hill close to the city centre but it was also on the wrong side of town for the newcomers. In fact, the first formal minyan south of the Clyde, at 2 Commerce Street, made its appearance in the same year that Garnethill opened.

By the turn of the twentieth century, the South Side was bracing itself to rival Garnethill in architectural terms. In 1901, Glasgow’s Central Synagogue opened in the heart of the Gorbals, at 93 South Portland Street (1898–1901). The architect was the Glaswegian James Chalmers (1858–1927) whose practice, by then in Hope Street, “consisted largely of episcopal church work, although he himself was latterly a member of Sherbrooke Church in Pollokshields”.48 South Portland Street Synagogue was planned to be “cathedral” in scale, the largest synagogue in Scotland, seating up to 1,600 people. The architect’s sketches, published in the Jewish Chronicle, showed an Islamic cupola on a hexagonal drum.49 Unfortunately, the project was badly over budget and the elaborate decoration of the proposed 81-foot wide Moorish façade was never carried out. A rare photograph shows a sober street façade, with a horseshoe arch, inset into the grey terrace (plate 5).50 Still, the gilded, domed, and turreted Ark owed much to Garnethill and to other Orientalist prototypes such as London’s St Petersburgh Place.51

Despite its pretensions, South Portland Street served a traditionalist community and incorporated a mikveh (the mikveh at Garnethill on the other side of the city was inconvenient for the women of the South Side). In 1885 the so-called “Glasgow Kosher Baths” were opened in the Gorbals’ Bathhouse in the heart of the immigrant “ghetto”. This was one of a number of mikvaot provided in public bathhouses by a city corporation during the second half of the nineteenth and first decades of the twentieth century. Such mikvaot were not paid for out of the public purse but were funded and operated by the Jewish community.52 In the 1900s the Gorbals Bathhouse mikveh was superseded by the new one at South Portland Street Synagogue. The synagogue was also home to the Glasgow Yeshivah and in September 1915 a beit ha-midrash (or religious study hall) was opened in the basement. Burdened with debt from the beginning (financial assistance from Garnethill notwithstanding), South Portland Street was the last Glasgow synagogue to close, in 1970, and was pulled down in 1974 during the wholesale demolition of the Gorbals slums. Today not a single Jewish building remains standing in the Gorbals.

Twentieth-century synagogues

A visit to Langside Synagogue in Glasgow provides a taste of a traditional immigrant shul interior. Behind an unpromising, vaguely modernist façade by Jeffrey Waddell & Young (1927) hides an unexpected little gem of an interior.53 The Ark and bimah and other decorative details including the clock on the gallery front were lovingly carved by a member of the congregation, a Lithuanian-born cabinet-maker called Harris Berkovitch (c. 1876–1956).54 Woodcarving and wall-painting in folk-art style was a characteristic of synagogue building particularly in Poland, Ukraine, and Romania. The Ark at Langside is two-tier, made of timber with gilding, in traditional Eastern European style (plate 6). The tall upper tier includes large gilded Luhot (Tablets of the Law) with painted glass panels to either side, and the pediment contains a Keter Torah (Crown of the Torah) with gilded sunrays, both motifs found in traditional Jewish art. The only other surviving example in Britain of a truly Eastern European-style synagogue interior is the Congregation of Jacob Synagogue in the East End of London, opened in 1921 and currently enjoying a revival. The future of Langside is in doubt. If it were to close, it is to be hoped that the high-quality fixtures and fittings would be salvaged and re-used. (There have been plans to redevelop the site as a sheltered housing complex incorporating a new, downsized synagogue, which would provide an excellent opportunity for such re-use.)

As this example demonstrates, by the turn of the twentieth century Jews were already moving out from the Gorbals into the South Side suburbs of Langside, Crosshill, and Battlefield. In 1906 a minyan was started in a private house at 140 Battlefield Road. Land in Lochleven Road was donated for a nominal sum by Sir John Stirling Maxwell, “Superior of the ground”,55 and plans were drawn up for the erection of the Queen’s Park Synagogue. However, the outbreak of the Great War, and the increase in the cost of materials that resulted, stymied ambition. A “tin Shool”56 of concrete with a “corrugated metal roof” was constructed at a cost of under £1,000. Surviving plans show a simple building with pitched roof covered with “asbestos tiles” with a “clay ridge”.57 The synagogue was to have five bays on the elevation to Lochleven Road, the lower-floor windows were to be shielded by a continuous rain canopy between the floors, and two vents with finials were indicated on the roof. This “temporary synagogue” was opened on 5 September 1915, accommodated 428 people, and had a single-storey classroom block to the rear. Its most indulgent feature was “an electric light installation”.58 It served until the erection of Queen’s Park Synagogue proper in the mid-1920s.

Plate 7 Queen’s Park Synagogue, Glasgow, view towards the Ark in 2002, before closure. Crown copyright RCAHMS.

Queen’s Park59 was a somewhat “retro” building, the interior of which, as mentioned earlier, owed much to Garnethill (plate 7; see plate 4).

Ninian McWhannell of McWhannell & Smellie designed Queen’s Park in 1924–7, behind a red-painted and rendered Romanesque artificial stone façade. It was closed in 2003 and sold to Arklet Housing Association, who converted the building into five flats. Access was reversed with a front door punched through the semi-circular Ark apse on Lochleven Road, perhaps prompting the housing association’s new name for the whole development – “The Ark”. The impressive vaulted vestibule, situated on the Falloch Road side of the B Listed building,60 was reminiscent of that at the Edwardian incarnation of London’s New Synagogue at Egerton Road in Stamford Hill (Ernest Joseph of Joseph & Smithem, 1915). Queen’s Park’s cycle of modern blue-hued painted and stained-glass windows by the Scottish glassmaker John K. “Jim” Clark, made to mark Glasgow City of Culture in 1989, was removed to Giffnock Synagogue courtesy of a £40,000 grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund. Finally, the Orientalist Ark was salvaged and successfully re-used (though its height had to be reduced to fit the space) in a new-build synagogue in Manchester, HaChodosh or the “New” Synagogue (surveyor R. E. Gonshaw, interior design by Joshua Benson, 2004) at 39 Northumberland Street, Salford, M7.

We have to turn to Edinburgh to emerge from the era that I have elsewhere termed “Edwardian Orientalism”.61 The Edinburgh Hebrew Congregation’s building in Salisbury Road, built in 1929–32, was the first and only purpose-built synagogue in the Scottish capital since the foundation of the community in 1816.62 Edinburgh Jewry has remained small by comparison with Glasgow, numbering about 100 in the 1820s, 2,000 at its peak in the 1920s and about 900 today (about 150 of whom were members of the synagogue in 2014). Designed by the influential Glasgow architect James Miller, Edinburgh Synagogue was put on the Scottish B List in 1996, judged an unusual red-brick building in the stone-built Scottish capital (“Byzantine” was the inaccurate stylistic label used at the time of its opening, presumably on account of the shallow ceiling dome). This Listing overturned the earlier, somewhat sniffy dismissal of it as “Post-Georgian”.63 It is not dissimilar to buildings of the same period by Cecil Eprile for the United Synagogue in London, but Miller’s work is superior. The four cubic corner turrets lend Edinburgh Synagogue a stark simplicity and a monumentality derived from the massing of the blocks. The brickwork is of high quality, utilizing Flemish bond and white mortar, conveying strength. Moreover, at the time, the brick shell masked advanced building technology. Inside, the saucer dome was suspended from the ceiling on state-of-the-art steel hangers. It still has splendid acoustic properties. The gallery was cantilevered with only vestigial column supports. However, the interior was fitted out in a reassuringly traditional manner. The Ark, of French walnut, has a classical pediment with a panelled surround, grilled choir gallery behind, and an octagonal pulpit in front. The bimah is placed in the centre following Orthodox Ashkenazi tradition, but with the seating all facing the Ark, perhaps suggesting mild Reform influence.

James Miller (1860–1947) was “one of the most prominent architects in Scotland”.64 His office was based in Glasgow (at 15 Blythswood Square), and not in Edinburgh, and it was there that he carried out most of his work. So how he came by this particular commission is an intriguing question. He did not specialize in ecclesiastical buildings but, rather, in civic and commercial projects, especially hospitals. Miller was influenced by the modernists practising in North American cities, such as Louis Sullivan, and shared their interest in the use of steel, the primacy of utility, and in the “clarity of structure” over ornamentation.

One sheet of Miller’s original drawings survives in the Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland (RIAS, the Scottish equivalent of the Royal Institute of British Architects; plate 8). This shows both a section through the Ark wall and the west elevation which, with its single central round-headed doorway, was clearly intended by the architect to be the principal entrance to the synagogue, rather than the current approach from Salisbury Road at the north. Today, the west front is hidden “around the side” by an ugly extension of the premises next door, sadly detracting from the impact of Miller’s original scheme.

By the 1980s the 1,000-seat building was too large for the needs of the declining congregation. In 1981 the architect Michael Henderson of Dick, Peddie & McKay carried out a scheme to reduce the interior volume by a half.65 The prayer hall was raised to gallery level by the insertion of a new floor. The ground-floor area was turned into a communal hall and Miller’s original hall next door was sold off for redevelopment. However, the by then disused mikveh and caretaker’s house, built as separate outhouses at the rear of the site in a style contemporary with the synagogue, were retained. In 2003 the mikveh was put back into use as part of the renovations to Edinburgh Synagogue with the aid of a grant of £300,000 from the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Contemporary Scottish synagogues

In the 1960s, Glasgow Jewry was forced to relocate en masse thanks to the wholesale demolition and redevelopment of the Gorbals. The Jewish Chronicle reported in March 1968 that “four out of the eleven synagogues in the [Glasgow] community will be situated outside the city boundary”.66 At that time no fewer than three substantial-sized new synagogues were built in the outer southern suburbs. In 2012 one of these, Netherlee & Clarkston (1968–70), closed, prompting a return visit by the SJBH to record the city’s postwar synagogues. Unfortunately, we arrived too late to photograph the interior that had already been dismantled. At least, this had been captured on camera for posterity by Harvey Kaplan of the Scottish Jewish Archives Centre (SJAC). Subsequently, the whole building was sold and was slated for possible demolition. The period grillework was salvaged and has been re-used to great effect in the refurbished beit ha-midrash (2012) at Edinburgh Synagogue.67 There, the whitewashed walls set off the black-painted metal screens and stained-glass windows, including two by the Edinburgh artist William Wilson (1905–1972). A member of the National Association of Decorative and Fine Art Societies (NADFAS), Bobbie Smith, has tried to identify the artists and makers of all of the stained glass at Edinburgh Synagogue (from 1931 onwards), but without much success. Smith agreed with Pevsner’s Glasgow that there are six windows by Wilson at Edinburgh Synagogue. However, we identified only five for certain: three windows on the theme of “Creation”, dated 1967, are located in the vestibule. Displayed on the wall next to them is a coloured cartoon by the designer. Wilson always signed his work, sometimes with his logo, a stylized St Giles Church, Edinburgh. It is thought that this logo appeared without his signature when a window was produced by his studio, not by him personally, as is apparently the case with one of the two Wilson windows in the beit ha-midrash.68 A member of the congregation, Edward Green, of the Queen’s jeweller’s Asprey, was responsible for the successful design of the refurbishment.69 He also commissioned a new clear-glazed Magen David to provide ample natural light into the beit ha-midrash.

Netherlee & Clarkston’s interior was of less architectural interest than the exterior, even though the latter seems to have resulted from a radical remodelling of an existing building on the site. The Jewish Chronicle report of the opening, which took place only seven months after the foundation-stone laying ceremony in 1968, referred to the project as a “reconstruction scheme”.70 In fact it seems that this synagogue went through several incarnations. Its precise building history has not been fully untangled, especially given the sparse visual record (this is surprisingly common even for relatively recent synagogues). The congregation was established during the Second World War (1940) and met “in a shop in Stamperland Hill”.71 It then moved to the site on the corner of Clarkston Road and Randolph Drive, where a new synagogue was opened in 1952. The only known photograph, in black and white and undated, shows adjoining buildings.72 From oral testimony it has been confirmed that the modest, single-storey building in the background, aligned to the east along Randolph Drive, was in fact the synagogue. The east wall is not visible in the photograph, but the long wall shown has prominent concrete buttresses separating the five bays filled with large rectangular windows, features consistent with the function of the building. Inside, “a sliding partition” was employed so that the rear of the prayer hall could double up as both classrooms and communal hall. In the 1950s and 60s the concept of “flexible space” became a fashionable solution for British synagogues with fluctuating congregations (typically, they were only full on the major holidays). “Flexible space” was pioneered in the 1950s by the Jewish synagogue architect Percival Goodman in American suburbia.73 Shown in the foreground of the Netherlee & Clarkston photograph is a plain brick building, also single-storey, with a pitched corrugated iron roof and Crittall-style metal-framed windows. Containing the main entrance at west along Clarkston Road, this building housed classrooms. (It has not been determined whether this block was a conversion or purpose-built, either at the same time or later than the synagogue itself.) Clearly, Netherlee & Clarkston Synagogue was typical of the 1950s, built out of the poor materials that were available while rationing was still in force in the years after the Second World War. It appears that railway sleepers were used in the construction of the floor of the synagogue and by the mid-1960s, these “were found to be unsound”. Thus a rebuilding programme was launched. In 1968 a new communal hall was added.74 In January 1970 the synagogue itself was reconsecrated by the Chief Rabbi.75 This marked the completion of “an extensive scheme of reconstruction” that included not only the hall but also “a new frontage, new foundations and a new roof”. A brand new Ark was also dedicated.

Thus, the distinctive white concrete tower and covered walkway of the building that closed in 2012 must have belonged to the final building phase in 1969–70. These were reminiscent of Ernst Freud’s synagogue (1957–8) at the lost London Jewish Hospital in Stepney Green which had been built in the 1950s.76 It is not known whether Clarkston’s architect, Andrew William Dougall Samuel of Strathclyde, was aware of this precedent.77 The project cost £40,000 and benefited from a loan from the Glasgow Jewish Community Trust. Samuel had already completed the first Newton Mearns Synagogue in 1968 on a similar budget (on which more shortly), the same year in which he became a Fellow of the RIAS. It is a puzzle how this Scottish architect landed two synagogue commissions; he is not known to have designed any churches. His biblical surname may indicate Jewish origins, but he was certainly not based in or near the Glasgow Jewish community.

Giffnock and Newlands Synagogue was claimed to be the largest synagogue in Scotland when it opened in time for Rosh Hashanah in 1968.78 It replaced the original Giffnock Synagogue in May Terrace (consecrated in 193879) that survives today inside the Maccabi Centre into which it was incorporated over 1967–70. This congregation was founded in 1933. May Terrace had begun life as a single-storey building, but was extended by unidentified architects after the Second World War to meet the demands of the expanding community which reached its peak in the 1970s. In 1949 a second storey was added at May Terrace in order to accommodate an upstairs ladies gallery (the concrete piers are still visible); classrooms and a youth centre were built.

A house at 222 Fenwick Road, together with a substantial amount of land on Maryville Avenue, was acquired in 1964 and ambitious plans were laid for a large prayer hall with seating for 1,150 on the ground floor and in the gallery, “a cheder block, banqueting suite and a ‘MIKVAH!!’[sic]”.80 (Giffnock’s mikveh is now the only one in Glasgow. It is a rare modern example of a basement mikveh on the Continental model.) Some £250,000 was raised for the whole project thanks to sound financial advice from Sir Isaac Wolfson (1897–1991), Glasgow’s most successful Jewish son. A member of the Giffnock Building Fund Committee, Dr David Granet, recalled making a successful approach to Sir Isaac and his brother Charles during a weekend visit to London, where they all prayed at Sir Isaac’s “private chapel”, the Central Synagogue, Great Portland Street, and afterwards met at Sir Isaac’s palatial home on Portland Place. Sir Isaac contributed £20,000 and Charles Wolfson £10,000 in order to kick-start the fundraising. Wolfson advised the committee to turn loans into gifts in order to avoid interest and attract tax breaks. Money was also raised by the sale of May Terrace to Maccabi and of land on Maryville Avenue to the Glasgow Jewish Housing Association, which built Walton Court. The congregation also acquired two houses, one each for the rabbi and chazan. Later on, from 1987, more land at Giffnock was sold off in parcels to the Glasgow Jewish Housing Association.81

It is therefore not really surprising that Giffnock Synagogue was modelled on the conventional large London United Synagogue type favoured by Sir Isaac in the 1960s. This was essentially an update of the nineteenth-century “cathedral synagogue” except that, internally, the galleries were constructed from reinforced concrete and steel cantilevers, rather than carried on iron arches. Giffnock’s façade is a whitewashed concrete frame, the severity of which is lessened by grey brick infill, expansive glazing, and a large angular menorah – a single, typically 1960s, piece of symbolic art used to identify the function of a building that would not otherwise be obvious. The roof has a parapet and is very high-maintenance.

Oral testimony from several informants named the Glasgow-based Baron Bercott & Associates as the architects of Giffnock.82 In fact, a perusal of the extensive synagogue archives (during a subsequent visit in 2012) revealed that Baron Bercott (1920–2005) was responsible for the repairs after a big fire in the synagogue hall in 1972.83 The hall and classrooms had only been built in 1969. Baron Bercott trained in Liverpool and initially joined the RIBA rather than the RIAS. By 1950 he had moved to Scotland and practised mainly out of Glasgow. Some of the confusion may have arisen over the fact that the Bercott family were known in the Jewish community. Baron’s father, the jeweller Solomon Bercott, was a member of South Portland Street Synagogue, but had married out of the faith.84 Moreover, Baron Bercott was the architect of Glasgow Jewish Primary School, Calderwood Lodge, that had opened in 1962.

Plate 9 Giffnock Synagogue, Glasgow, architects’ perspective drawing, signed by Norman Bailey, Samuels & Partners, not dated. Courtesy SJAC.

The original architects of Giffnock were a London firm, Norman Bailey, Samuels & Partners (plates 9 and 10).85 Indeed, “Mr Samuel” had been “recommended by the United Synagogue, London”,86 for which he had previously worked. Presumably, the Glasgow commission arose through the good offices of Sir Isaac Woolfson. Alfred Fox Samuels joined Norman Bailey, who was based in Lambeth, after training at the Northern Polytechnic (a Gerald Samuels was operating from the same address in 1972, but as Gerald Samuels Associates – perhaps Alfred’s brother?). Alfred became a Fellow of the RIAS, but only a member of the RIBA (1950–75; registered with the Architects’ Registration Council [Board] until 1977). Norman Bailey, Samuels & Partners was established in London in 1950 and afterwards had branch offices in Manchester and Glasgow. (A subsequent partnership between Samuels and the non-registered George Malcolm Steel was dissolved in September 1970.)87

The colossal bill of £250,000 for Giffnock did not escape criticism at the time, especially given the rash of synagogue building in Glasgow stimulated by the redevelopment of the Gorbals.88 Under the headline “Too many communal buildings?” the JC reported on a meeting of the Glasgow Jewish Representative Council at which Dr. Jack E. Miller complained about the “useless buildings” going up on the South Side.89 He was frustrated at the ambitions of smaller South Side congregations like the Chevrah Kadisha (as discussed earlier) to build their own places in the suburbs rather than amalgamate with the larger congregations that had formed there, in that case Netherlee & Clarkston. The Chevrah Kadisha pressed on with abortive plans to build a synagogue of their own for four hundred people in Crosshill at a cost of £40,000 (the proposed site was at the junction of Cross Hill Avenue and Queen’s Park Avenue; in the end they merged with Pollokshields Hebrew Congregation in Nithsdale Road in 1972). Meanwhile, the existing Crosshill Hebrew Congregation that had met in a terraced house in Dixon Avenue since 1932 built a modest new synagogue of its own at Belleisle (or Belle-Isle) Street in 1960–61. The single-storey structure had a brick frontage decorated with a discreet Magen David in the gable. Behind, the building may even have been constructed of timber – it certainly had a shed-like appearance – and the interior was wood-panelled. Its only real interest was the ceiling painted in bold 60s patterns, the full impact of which can only be guessed from the surviving black and white photograph.90 The architect – if there was one – has not been identified.91 The patron Sir Maurice Bloch ensured that the building, costing an estimated £11,750, opened free of debt.

A “turf-cutting ceremony” for a new synagogue in Newton Mearns was held in April 1966.92 Newton Mearns is south of Giffnock; the congregation began life after the Second World War, in 1954, and had met in a former parish hall. The foundation stone at Beech Avenue (preserved at the current synagogue) was not laid until June 1968.93 The two purpose-built synagogues, at Giffnock and Newton Mearns, had been in planning at the same time and both received planning permission from Renfrewshire County Council in 1964.94 However, in the case of Newton Mearns, the project ran into funding difficulties when the bank refused a loan of £45,000 because of “Government economic restrictions”.95 Of the estimated £65,000 needed, £10,000 was contributed by Glasgow Jewish Community Trust. In the end, a “prefabricated” building was erected in time for the High Holy Days in 1968.96

Curiously, like Giffnock, Newton Mearns also suffered a fire, in 1973. The prefabricated building was “almost a complete write-off”. Worse, one of the Torah scrolls was destroyed.97 The cause of the fire was not explained. It was immediately resolved to rebuild for the congregation of 450. Thus the foundation stone of a new synagogue was laid in March 1977 and the building seems to have been opened for worship sometime the following year.98

Designed by Andrew William Dougall Samuel, the interior of this building is of some architectural interest. With seating for five hundred, the prayer hall was built to the “broadhouse” plan in which the Ark is situated on the long east wall. This is a layout found in ancient synagogues excavated in Israel and elsewhere in the Middle East (most famously at Dura Europos in Syria), as well as in some sixteenth and seventeenth-century Sephardi synagogues, notably in Venice. At Newton Mearns the rear wall facing the Ark can be opened out to merge the hall with overflow seating for the High Holy Days, an arrangement typical of big synagogues of the 1960s in both Britain and America. The interior is top-lit through a high roof-lantern in front of the Ark. The open-timbered ceiling is impressive and unusual, especially for this period, but highly impractical for changing the light bulbs (roof access is also difficult). In May 1979 the JC reported that the high cost of paying for a new synagogue was reflected in the accounts of the Newton Mearns congregation, which showed an overdraft of more than £150,000.99

The most interesting modern synagogue in Scotland is not to be found in either of the capitals but up in Dundee. Ian Imlach’s Dundee Synagogue, St Mary Place (1978–9),100 was built under the patronage of a single patron, Harold Gillis (d. 2001).101 Dundee City Council presented the congregation with the land as compensation for the compulsory purchase of their previous synagogue in a converted warehouse down by the docks that was demolished in 1972 (see earlier in respect of Dundee’s Jewish cemetery). The blank brick, roughcast, and whitewashed walls of the new building slope at an angle of eighty degrees and the twisted hyperbolic roof is covered in grey Scots slate. The whole presents a fortified appearance, a characteristic of many synagogues built since the 1970s. Despite, or perhaps because of, this, the walls were covered with graffiti soon after the synagogue opened. The minimalist interior is painted in neutral tones and features stylish use of natural materials: red pine for the ceiling, contrasting with the blue glazed-tiled tevah surrounded by pebblestones, woollen textiles, and carpets (tevah is the term used by Sephardi and Oriental Jews for the Ashkenazi bimah). This synagogue has a double Ark, the only one in Britain. Double and triple Arks are a feature of synagogues in some Sephardi and Oriental Jewish communities, especially in North Africa. Perhaps the architect was influenced by trends in Israeli synagogue design. It has been claimed that the inspiration came from Iran. In any case, this is somewhat bizarre given the “non-existent” Sephardi (let alone Iranian) Jewish presence in Dundee (it has been suggested that Dundee’s tevah was designed to accommodate a tik, the wooden case protecting the Torah scroll, used by North African and oriental Jews. The case is opened on the tevah when in use, the scroll remaining inside it, unlike in the Ashkenazi and Spanish and Portuguese traditions where textile mantles are removed from the scroll before it is opened).102 The materials and colours, while attractive, do not make a successful transition from the Mediterranean to Scotland and the design concept has not been taken up elsewhere.

Legacy

Glasgow’s Jewish community, although much diminished (about 3,400, in the 2011 Census), remains the largest in the kingdom, accounting for just over half the total Jewish population of Scotland, which is put at nearly 6,000. As we have seen, Glasgow Jewry has decamped to the outer suburbs on the South Side, mainly around Giffnock, East Renfrewshire. Nevertheless, Edinburgh’s community shows a marginal increase in numbers and the Being Jewish in Scotland project (2013) of the Scottish Council of Jewish Communities revealed individual Jews scattered all over the country.103 Tiny communities work to support the synagogues of Aberdeen and Dundee, and an online “Jewish Network of Argyll and the Highlands” has been set up. Whether there will ever be enough Jews on the ground to form a community in the West of Scotland remains to be seen.

Plate 11 Gable symbolism: Glasgow Reform Synagogue, Ayr Road, Newton Mearns, is housed in a parish hall that was converted into a synagogue in 1969. Photograph Viorica Feler-Morgan for SJBH.

Glasgow possesses a legacy of grim disused burial grounds that are the responsibility either of the city council or the Jewish community. Back in 1999 four of the eight Jewish cemeteries in the city were classified by our Survey as “At Risk” from neglect, vandalism, or general urban blight. These included the Eastern Necropolis, the Western Necropolis, and Riddrie. By the time of our return visits in 2012 and 2014, as has been observed in this article, there were encouraging signs of improvement, reflecting investment by the local authorities in the restoration of public parks and gardens. Moreover, cemeteries are now classified under “Parks and Gardens” by governmental heritage agencies and the Heritage Lottery Fund in both England and Scotland. The privately owned Craigton Cemetery was completely impassable back in 1999 but by 2014, having passed into local authority control, the whole site had been restored. As we have also seen, Glasgow City Council was commendably receptive when their attention was drawn to the virtual disappearance of the Jewish section under a sea of brambles, resulting in a clearing-up operation.

Generally speaking, Jewish plots that are in use in Scottish cemeteries managed by city, district, or county councils, are well-maintained and often pleasantly landscaped and planted with flowerbeds – in stark contrast to many Jewish-owned cemeteries where excessive use of chemical weedkiller ensures the survival of not a single blade of grass. The harsh treatment of the Jewish section of the Western Necropolis is testament to this (the plot is maintained by the city council in collaboration with the Glasgow Hebrew Burial Society). It well illustrates the need for some cultural re-education about environmentalism within the Jewish community.104 Change is slow, but the establishment of the Friends of Sandymount Jewish Cemetery in 2004, on the private initiative of families with ancestors buried there, has led to great improvement in the appearance of that particular site.

As tombstone inscriptions – which were carved in stone supposedly for eternity – weather away, we lose the stuff of social history, to say nothing of family history research. SJAC has worked hard to rescue and protect fragile vital records. However, they have succeeded in acquiring only a small number of original burial registers. All too often in the past these have been lost. Family historians have stepped in, carrying out field surveys to document surviving tombstones and thus help fill in gaps in the digital data. The SJAC database (not available online) is compiled from a combination of incomplete burial records and field surveys of Jewish cemeteries throughout Scotland. It is a magnet for genealogists.

Over the past twenty years Scotland’s historic synagogues in both Glasgow and Edinburgh have benefited from public grant aid for repairs through both the Heritage Lottery Fund and Historic Scotland. This is testimony in itself to wider recognition of their national importance to the architectural heritage of both Scotland and the UK. Matched funding has been forthcoming from the Wolfson Foundation, founded by Sir Isaac Wolfson.

It is easy to forget that back in the 1980s Garnethill Synagogue was battling for its very survival. It found itself marooned in the city centre, increasingly isolated from the centre of gravity of Glasgow Jewry that had shifted to the South Side suburbs. This is a predicament faced by other major Victorian synagogues such as Liverpool’s Princes Road, Birmingham’s Singers Hill, and Brighton’s Middle Street. Garnethill’s survival has owed much to the pioneering work of SJAC that, from 1987, made its home in the basement. SJAC has rescued and stores a wealth of original material besides burial records, for example more than six thousand historic photographs that document the history of Jews all over Scotland. Thanks again largely to the Heritage Lottery Fund, in 2008 a permanent exhibition was installed (designed by Artan Sherifi of Arka Design Studio and Paula Murray and Alan Mackay). The corridor approach displays a timeline of the history of the Jews in Scotland.

Today, while no physical trace of Jewish life in the Gorbals remains, Garnethill not only continues as an active place of worship but also serves as a repository for the history of Scottish Jewry. Above all, it has retained its powerful symbolism as a landmark building that expresses the continuity of Jewish life in Scotland. Truly the “cathedral synagogue” of Scotland, it may yet become the Jewish Museum of Scotland.105

A note on traditional sources and internet research

Dating in this article is based wherever possible on primary research in the archives, that is, manuscript sources such as building committee minutes, architectural plans and sketches, leases and title deeds, as well as contemporaneous printed material such as old maps, photographs, orders of service, and newspaper reports. Increasingly, this kind of material is being catalogued, sometimes scanned and placed online, thus making a trip to the archives less crucial.

Regarding burial registers: online databases of Jewish cemetery records have made great strides over the past decade and are a great aid to family history research (see especially JCR-UK, the Jewish Communities and Record Database [www.jewishgen.org/databases/UK] and Cemetery Scribes [www.cemeteryscribes.com]). However, at time of writing neither site has comprehensive coverage of Scotland. The SJAC’s database can probably claim the greatest completeness, but is not available online. Generally, online databases are designed primarily for searches by name, making it difficult to establish from them the dates of the earliest burial in a given cemetery. It is also hard to determine exactly which primary source, or combination of sources, is the basis of the information that they contain. Above all, we need to remind ourselves that such resources may not be a hundred per cent accurate and can never entirely replace the original documents that must be conserved and protected in a secure place. In the long run, the existence of digital records will help preserve the fragile paper records by reducing the wear and tear on them by users.106