A woman stands alone on the deck of a ship, caught between memories of the luxurious life she has left behind and doubts about a new beginning in a strange land. This powerful image from Grace Aguilar’s short story “The Fugitive” (1852) hints at a wider Sephardi imaginary relating to the flight of Iberian conversos to England. Aguilar’s story refers to a specific episode in Anglo-Jewish history, that of the arrival of Sephardim in the first half of the eighteenth century. A. S. Diamond estimated the numbers of Portuguese conversos who arrived in England between 1720 and 1733 to be about 1500, the highest figure ever registered.1 Most of these exiles arrived with little more than memories of a life lived under bigotry and persecution. These memories were passed from generation to generation and became part of a Sephardi oral tradition that writers such as Aguilar inherited and disseminated.

This article will focus not on the empirical details of historical events but on the different ways in which these events are represented. We will analyse the portrayal of one historical phenomenon – the eighteenth-century Portuguese converso migration to England and its background – from three distinct angles. The first perspective is that of Michael Geddes (c. 1650–1713), the author of an anti-inquisitorial essay whose protagonist is a Portuguese Jew who has experienced imprisonment at the hands of the Inquisition. The second section analyses the way in which the nineteenth-century Jewish author Grace Aguilar, a descendant of Portuguese New Christians, draws parallels between the inquisitorial persecution of conversos in eighteenth-century Portugal, some of whom fled to England, and the challenges faced by the Jewish minority in Victorian Britain. Finally, the focus will move to the testimonies given before the Inquisition by those exiles who returned to Portugal after a period of having lived openly as Jews (or simply among the Jewish community) in London. Like Geddes’s and Aguilar’s writings, these testimonies will be considered as constructed narratives with specific aims that determine their contents.

These three narratives converge in representing religious conversion as a recovery of roots and a return to an original faith. This idea will be the cornerstone of this article. The identification of an “original faith”, whether Jewish or Christian, is determined by the specific goals and target audience of each narrative, reflecting the complexity, ambiguity and multilayered nature of Iberian converso or New Jewish identity and its representations.2 In a recent article, David Graizbord concludes that “the men and women of the Nation were potential Jews and potential Christians simultaneously.”3 This assumption is particularly the case with regard to the depiction of the converso and the New Jew (referring to a new convert to Judaism).4 The three examples here analysed show how the aims of a given narrative determine whether the converso, whose identity lies in the unstable space between faiths, is perceived as either a potential Jew or a potential Christian.

London’s eighteenth-century Sephardi community offers a fascinating arena in which to explore these themes. The arrival of unprecedentedly high numbers of newcomers in this period, who had lived their whole lives as Catholics, raised serious challenges for their integration into the community and adaptation to Jewish life. At the same time, anti-Catholicism was flourishing in England, and these converso newcomers, who had suffered the iniquity and ruthlessness of the Iberian Inquisitions, appeared to constitute both a ready supply of potential converts to Angli-canism as well as an effective weapon in the fight against “Popery”.

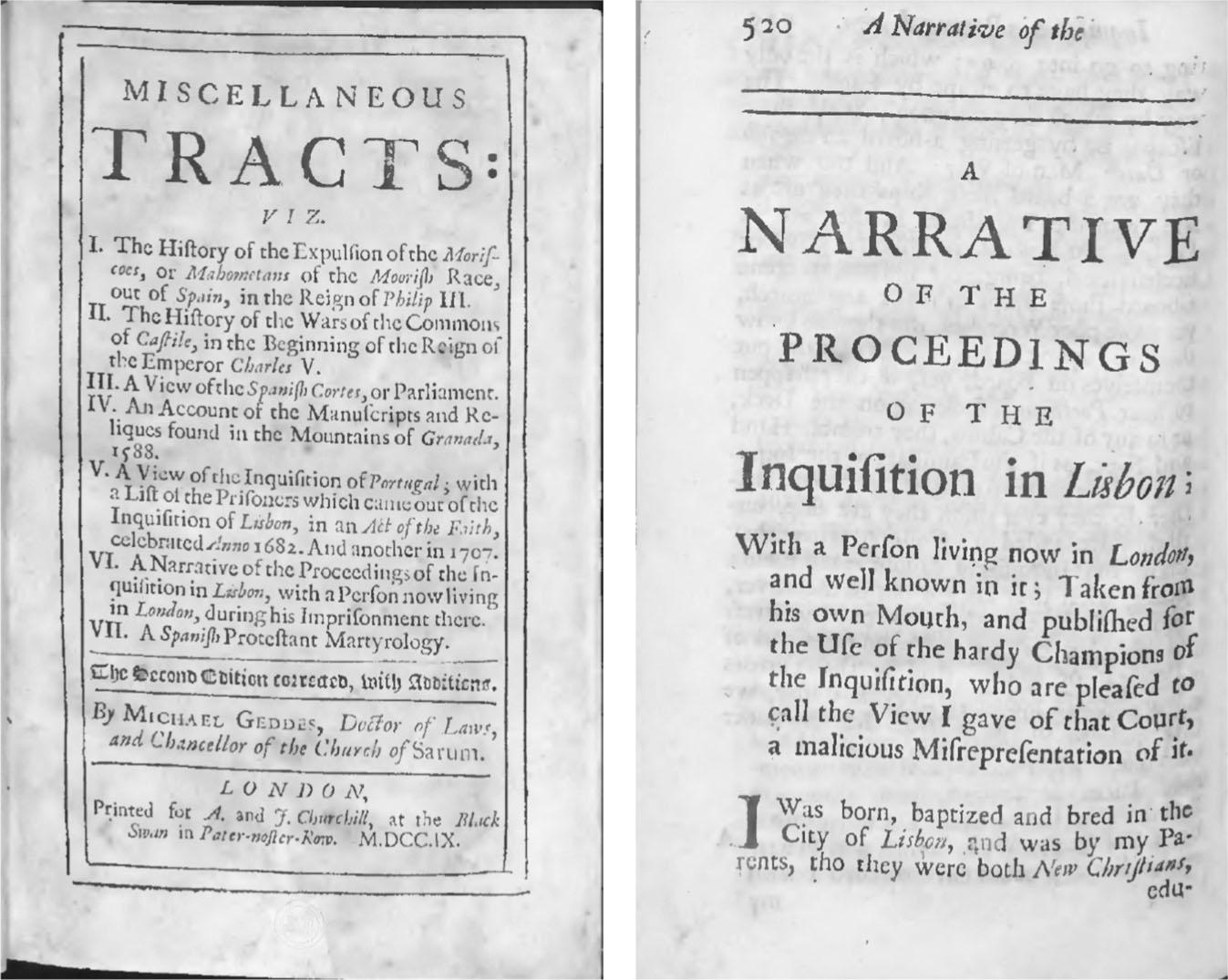

Title page of Michael Geddes, Miscellaneous Tracts (1709 edition) and first page of “A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Inquisition of Lisbon”. Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, Lisbon

The prisoner

The first volume of Michael Geddes’s Miscellaneous Tracts, originally published in 1702, includes a rare example of an allegedly first-person account of a Portuguese Jew of London relating his experiences in the dungeons of the Inquisition: “A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Inquisition in Lisbon with a Person living now in London and well known in it”.5 Although its writing had preceded the peak of the Sephardic migration to England, Geddes’s “Narrative” was successively republished until the 1730s as part of other polemical works.6

From 1678 to 1686, Geddes was the Anglican chaplain of the English Factory in Lisbon, a corporate structure formed by English merchants, agents, and factors residing in the city. In 1686, he and the consul, Thomas Maynard, had been brought before the Inquisition of Lisbon because of religious services held in the consul’s house. In their defence, Maynard cited article 14 of the 1654 Treaty of Peace and Alliance between England and Portugal, according to which the English could freely “observe and profess their religion in their own private houses” in Portugal. However, despite this defence, Geddes was dismissed from his position in Lisbon and had to return to England.7 This episode, as well as the violence of the autos da fé that Geddes attended during his mission in Lisbon, fuelled a hatred of the Portuguese Inquisition that later found expression in his writings.

The objective of the “Narrative” is openly stated in the second part of its title. After clarifying that this was an account “taken from his [the witness’s] own mouth”, Geddes emphasizes that it was “published for the use of the hardy Champions of the Inquisition, who are pleased to call the View I gave of that Court, a malicious Misrepresentation of it.” The “View” is an essay included in the same volume of Miscellaneous Tracts, in which the author critically describes the functioning and proceedings of the Portuguese Inquisition, with a special focus on the ceremony of the auto da fé.8 Therefore, the “Narrative” aimed to strengthen his arguments with the emotive force of first-person testimony, complemented by a final dialogue between the author and the narrator.

The text begins with the account of a Portuguese New Christian arrested by the Inquisition who ends up fleeing to London, where he adheres to Judaism. Geddes does not reveal his name but gives some data on his identity: he was a merchant aged twenty-five from Lisbon when imprisoned. It is uncertain whether this merchant represents a real person or is simply a typological character. The former seems more likely since the mention of him as someone “well known” in London might have provided a clue to a contemporary reader as to the identity of a real person. In any case, it is clear that the supposed real testimony has been supplemented with a combination of the author’s readings and oral testimonies collected in London and Lisbon. In this regard, the “Narrative” reproduces some common elements of anti-inquisitorial literature, which flourished with special vigour in England from the last decades of the seventeenth century: these themes included unfounded arrest, miserable prison conditions, trial delays, attempts to force a confession, treacherous cellmates, sham opportunities of defence, forged confessions, torture (which fills about a quarter of the account), and deprivation after release.9 The same topics are addressed in An Account of the Cruelties Exercised by the Inquisition in Portugal, published in London six years after Geddes’s “Narrative”, and which was an English translation of a Portuguese text written in the 1670s that had already circulated throughout Europe in manuscript. In 1722, the first edition of this text in its original language was printed in London at the instance of David Nieto, the Hakham of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews’ Congregation, under the title Noticias Reconditas y Posthumas del Procedimiento de las Inquisiciones de España y Portugal con sus Presos.10

In the Noticias, just as in Geddes’s “Narrative”, the Inquisition is accused of being responsible for driving the conversos away from Christianity because of its cruel and merciless methods. However, the texts have different backgrounds, aims, and target audiences. The Noticias was the expression of the efforts undertaken by the Portuguese New Christians to reform the Inquisition’s methods, while the “Narrative” could be better framed in the context of seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century English anti-Catholic literature. Despite this, both texts highlight the Christianity of the conversos punished by the Inquisition. Geddes stresses his protagonist’s deeply held Catholic faith, which was only undermined by his lengthy incarceration, during which time “I never saw a Confessor, nor did I ever hear Mass, nor was I ever spoke to, to exercise any of the Rites of Worship.”11 The accusations of Judaism are completely false: the Portuguese protagonist is an innocent victim of a rapacious tribunal whose only crime is to be a converso and, probably, a rich one. This perspective became a commonplace in anti-inquisitorial literature, even among Christian polemicists in England.12 For instance, the anonymous author of Authentic Memoirs concerning the Portuguese Inquisition (1761) ironically noted that “in a country so scarce of fewel, they can still find furzes and faggots enough to burn New Christians, many of whom, tho’ condemned for Judaism, have been incontestably proved, after they were consumed to ashes, to be far better Catholics, even in the Popish acceptation of the word, than the Lords Inquisitors themselves.”13

By stressing the inner Christianity of the “Narrative”’s protagonist, Geddes achieves two objectives: first, he strikes a blow against the Inquisition; second, he allows for the possibility that the former converso, now a New Jew, might return to his “original faith” (that is, Christianity) by an alternative and smoother path – the Church of England. This is the key idea of the second part of “Narrative”, in which Geddes recreates a dialogue with his protagonist. The “Christian potential” of his interlocutor is reinforced by the apparent mutability of his religious convictions. The Portuguese, when asked why he adhered to Judaism in England when he was a sincere “Romanist” in Portugal, replies in pragmatic, non-religious terms: “being by Birth a new Christian, he had some Relations among the Portugueze Jews in London, by whom he was kindly entertained, and who did all speak Portugueze, or Spanish, which were all the Languages he understood.”14 Social solidarity and linguistic facility are the first motivations he points to in order to justify his shifting religious alliances. Later, the Portuguese refugee develops his arguments, based on a wider sense of belonging to a historical reality that connected conversos and Jews: “Being himself of the seed of Abraham, and of the Tribe of Judah, he said he was convinced he could be saved in no other Law, but in that of Moses.”15 This is how he reacts to Geddes’s attempt to drive the dialogue towards the possibility of his conversion to Protestantism. However, the Portuguese makes clear that he is not receptive to such arguments and closes the discussion with the statement that everyone who “led holy lifes” should be saved despite the “sect” they follow. Everyone, but with two exceptions: Jews who do not profess the Law of Moses, and the inquisitors themselves. While Geddes overlooks the first exception, he emphasizes his interlocutor’s hatred of the officers of the Inquisition, thus fulfilling the other key objective of his “Narrative”.

Geddes relegates the Jewish/converso question to second place. Even when the Portuguese refugee identifies his innate Jewishness (“the seed of Abraham”), the author does not develop this topic and prefers to emphasize his interlocutor’s reluctance in maintaining a theological debate with him as indicative of the weakness of his arguments. Also, the non-religious motivations for his embrace of the Jewish religion serve to consolidate the stereotypical image of the Iberian converso or New Jew as someone whose faith is sufficiently mutable as to make them easily convertible.16 Therefore, the Portuguese refugee interests Geddes not so much as a Jew but as a victim of the Inquisition (and, by extension, the Catholic Church) and a potential Christian. His Jewishness was only a transitory stage that should culminate with his “return” to Christianity. In this sense, Geddes’s “Narrative” is an example of the “philosemitism” that had been a feature of English Protestant polemical literature since the Restoration, in which Jews were valued as potential converts whose accounts of Inquisitorial oppression could be used as a weapon against “Popery”.17

The fugitive

A century later, a perception of wavering Jewish religious belief combined with the miserable living conditions of a significant number of Jews living in England spurred the efforts of conversionist Christian organizations such as the London Society for Promoting Christianity among the Jews.18 The Jewish communal leaders offered a tailored reaction, boosting their educational and philanthropic endeavours. Several Jewish authors also formulated responses to Christian proselytizing that deeply contributed to raising Anglo-Jewry’s consciousness and increasing social empowerment.19

Isaac Lobatto Rz, Portrait of Grace de Aguilar, 1831–63.

Lithograph, 12.2 × 9.1 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Grace Aguilar (1816–1847) was one of the most prolific authors to offer a conscious response to the new challenges facing Victorian Anglo-Jewry. In order to combat the threat of Christian evangelism and the persistence of prejudices and social discrimination, she looked to develop her arguments around her Sephardic roots.20 Aguilar was a descendent of Portuguese converso exiles who had settled in England in the 1720s. Her maternal great-great-grandfather, Daniel Dias Fernandes (born in Freixo de Numão or Oporto, c. 1690–London, 1759), had moved to London before 1722, where he married Sarah de Aguilar, the sister of Diogo Lopes Pereira, Baron of Aguilar (Oporto, 1699–London 1759).21 The latter had also left Portugal in the early 1720s and was the great-great-grandfather of Grace’s father, Emanuel Joseph Aguilar.22 Despite the remoteness of Grace Aguilar’s connection with Portugal, references to her roots are ubiquitous in her work. Her Sephardi upbringing and its associated oral tradition, preserved over generations, gave her abundant material for both her fictional and non-fictional work.

Medieval Iberian Jewry, expulsion and forced conversion, the Inquisition and escape from the Peninsula are recurrent topics in her short but fruitful literary career.23 Aguilar links these subjects to the contemporary challenges of Jews in England. She reads the bias of English society as result of its ignorance about Jewishness and seeks to correct the misunderstandings that lead to prejudice through her writing. She openly addresses this objective in the preface of Records of Israel.24 Her efforts were particularly focused on the dissemination of a new and improved image of Jewish women within Victorian society.

Indeed, two Portuguese Jewish women, Almah Diaz or Rodriguez and Inez Benito, are the respective protagonists of Aguilar’s short stories “The Escape: A Tale of 1755” and “The Fugitive: A True Tale”.25 Both are narratives of religious persecution and evasion set in an eighteenth-century Lisbon under the yoke of the Inquisition. In “The Escape”, Alvar Rodriguez, Almah’s husband, is arrested after being denounced by “Señor Leyva”, a former guest of his home who is in reality a spy in the service of the Holy Office. Almah reacts by trying to gain Alvar’s freedom at any price, going to the length of disguising herself as a Moorish man in order to infiltrate the Inquisition’s prison. The predicament of Inez in “The Fugitive” is slightly different. She is a young widow denounced by her brother-in-law, a man she had refused to marry. The fear of arrest by the Inquisition forces her to flee Portugal on board an English ship.

Both Almah and Inez embody the stereotypical features of the Romantic belle juive: beauty, modesty, and loyalty.26 However, the exceptional situations they are forced to face bring out other attributes, namely their remarkable courage, intelligence, responsiveness, and capacity for self-sacrifice. Aguilar makes readers empathize with the characters by focusing on qualities of personality not exclusive to Jewish women and highly valorized by Victorian society.27 After all, her target audience was not only Jewish but also Christian readers, among whom her works were quite popular.28

Almah and Inez are portrayed as women of a high social rank. The same is the case with other Jewish characters in both stories. For instance, Judah Azevedo, Inez’s suitor, is a rich London Jew, whose family is described as “one of the very highest families of the proud and aristocratic Portuguese.”29 This depiction accords with the Sephardi idealization of a noble background, which nourished their “aristocratic pride” and sense of superiority in relation to both Jews and non-Jews, the origin of which dates from before the Expulsion and acquired new modes of expression in the Diaspora.30

Almah and Inez’s social and economic status do not, however, save them from the Inquisition. In fact, it is precisely Alvar Rodriguez’s wealth that is the source of his misfortune.31 The Inquisition’s greed emerges from the description of Inez’s abrupt flight: she could take with her only a small parcel with some jewels saved “from the rapacious hands” of the tribunal.32 The persecution they suffer is not the consequence of the Jewish rituals that Inez, Alvar, and Almah practice in the privacy of their homes, but rather due to the jealousy and desire for revenge they attract because of their wealth and high social status.

Alvar Rodriguez is simply described as “a Jew”, “one of the many who, in Portugal and Spain, fulfilled the awful prophecy of their lawgiver Moses, and bowed before the imaged saints and martyrs of the Catholics, to shrine the religion of their fathers yet closer in their hearts and homes.”33 Secrecy, concealment, and masking define the religion professed by Aguilar’s heroines and their families.

The author assumes that this situation would be strange for most of her English readers. Having in mind a Christian audience, but also a Jewish one to whom crypto-Judaism was already a distant memory, Aguilar describes the secret Jewish practices from an outsider’s point of view.34 This is particularly evident in the description of Almah and Alvar’s marriage at the beginning of “The Escape”. First comes a brief report of the Christian ceremony in the church of “the little town of Montes”, followed by a party in the bridegroom’s mansion. “Montes” is a fictitious place, presented as a town situated 40–50 miles from Lisbon, whose name is probably inspired by the north-eastern Portuguese region Trás-os-Montes. While the guests are entertained with fireworks, the couple and a small group of close friends and relatives retire to an anteroom, where the Jewish ritual is performed. Aguilar gradually creates tension, increased by the bride’s fearfulness, leading to a description of the ceremony that betrays a certain distance with regard to Jewish religious practices, a distance implied in her rhetorical question: “What were those strange mysterious rites with which in secret he celebrated his marriage?”35

Aguilar does not understand the dual religious life of Iberian Jews as a sinful experience that should be erased from the memory of Jewish Diaspora, but rather as evidence for a Jewish commitment to faith despite danger. Almah and Inez are symbols of an almost unbelievable resilience.

When the worst fears come to pass and the Inquisition springs into action, normal life is shattered. Aguilar portrays this rupturing through Inez’s sudden flight to London and Almah’s cross-dressing in order to deceive the Inquisition’s officers and free her husband. Both are forced to renounce their condition as mothers, leaving their children in the care of relatives (Inez’s cousin Julian Alvarez) or servants (Alvar’s Moorish secretary, Hassan Ben Ahmed). For an author such as Aguilar, a champion of female domesticity, the depiction of this maternal sacrifice is particularly significant and exceptional in her work.36 Even more exceptional is the way in which it occupies a modest place in both stories, exceeded in importance by Inez’s abdication of her social condition and Almah’s full devotion to her husband.

Aguilar finds justification for such unnatural behaviour in the dramatic circumstances to which the characters had been exposed.37 The perversity of the Inquisition is demonstrated in its forcing two exemplary mothers and wives to transgress not only their maternal condition but even their gender. Ultimately, according to Aguilar, Almah even challenges the laws of God.38 The discovery of Almah’s scheme to free Alvar results in the couple being relaxados (faced with the death penalty). The sentence is not executed only because of the Great Earthquake of 1755. This catastrophe grants them the opportunity to escape. However, during this episode, the focus turns to Alvar, with Almah almost disappearing from the narrative. From this point on, she is completely subordinate to her husband’s actions and decisions. Michael Galchinsky perceived Almah’s loss of voice in the last part of the story as another punishment for her gender transgression, besides the failure of the escape plan she had conjured up to free Alvar.39 At the same time, this moment also marks the beginning of Almah’s return to her original role as a modest and submissive wife, who surrenders to her husband the responsibility for their safety. The exceptional time of transgression comes to an end and the couple’s arrival in London marks their return to normality. Almah and Alvar are reunited with their son, who had been moved to safety through the efforts of their loyal secretary, Hassan. Almah’s guardian, Gonzalos, and his family had also settled in London, a turn of events that “removed their last remaining anxiety, and gave them increased cause for thankfulness.”40

In the case of “The Fugitive”, although Inez arrives in London with only a “letter hurriedly written by her cousin to one of his friends” as credentials, she is warmly welcomed.41 Her first step is to ask her hosts how she can make a living there. However, this move towards independence is not pursued. Aguilar immediately changes tack, stressing how Inez’s female charm, exoticism, and moving story captures the interest of all. During an evening at the home of a friend of her host, Inez meets a former pretender to her hand, Judah Azevedo (“the richest Hebrew in London”), whom she ends up marrying. Years before, during a trip to Lisbon, Azevedo had met Inez and secretly fallen in love with her. At the time, she was still married, and he could not reveal his feelings for her. Now in London, his long-held admiration could finally be expressed and Inez, despite not sharing the same deep feelings, accepts his proposal and becomes the most “tenderly affectionate” and “devotedly faithful” wife – a destiny perfectly aligned with Aguilar’s ideal of female domesticity. Meanwhile, her son has joined her and Inez can regain her motherly role.42

Inez and Almah’s stories are almost certainly fictitious, although Aguilar tries to convince the reader of their veracity. Aguilar concludes “The Fugitive” by remarking that she had “heard it said that even in her coffin” Inez retained her beauty.43 In the final words of “The Escape”, Aguilar relates that “to this very day, his descendants [those of Alvar Rodriguez] recall his providential preservation by giving, on every returning anniversary of that awful day, certain articles of clothing to a limited number of male and female poor.”44 It is notable that these concluding segments both point to the influence of Aguilar’s family oral tradition. In fact, the only written source she mentions is John Stockdale’s The History of the Inquisitions, in particular the episode of the escape of a Mexican prisoner, Don Estevan de Xeres, from the Inquisition of Lisbon with the help of a loyal slave, Zamora.45 Her main source must have been the tales of escape from Iberia recounted by her parents and other relatives she had heard from childhood. Such escape stories would have been common among the Portuguese and Spanish Jews settled in London and it is possible to find traces of their sources in the Inquisition’s records, or even in the diplomatic correspondence of Portuguese and English agents in London and Lisbon.46

Another episode of Anglo-Sephardi memory recalled by Aguilar is the adventurous story of Garcias, a Portuguese merchant living in Lisbon around the middle of the eighteenth century. This story is addressed in her essay “The History of the Jews in England”, originally published in the Scottish journal Chambers’ Miscellany (1847) and republished in her posthumous Essays and Miscellanies (1853). Following the history of the Jewish presence in England from the Saxon period to contemporary times, Aguilar’s “History” refers to the Iberian background of the British Sephardim only twice: in a passage on the life and work of Menasseh ben Israel and at the end of the essay, through Garcia’s story.

The narrative begins with Garcia’s arrest by the Inquisition while celebrating his younger daughter’s birthday. He is then taken to the prison, where he remains for more than seven years. Here, Aguilar briefly addresses some commonplaces of anti-Inquisitorial literature: the arbitrary use of torture, the forced confessions, and the greedy confiscation of assets. However, her focus is on Garcias’s resilience, expressed through his constancy, ingenuity, and the courteous and gentle manners he maintains even within the prison. This passive resilience is reflected in behaviours that nearly feminize him. For instance, in an attempt to gain favour Garcias goes to the length of knitting socks for his jailors’ children. In this way, Aguilar subtly recovers the theme of gender transgression in relation to inquisitorial persecution that she had already addressed in “The Escape”. Just as Almah’s efforts to deliver her husband had forced her to assume new roles, incarceration was a time of exception for Garcias, during which he had to change for the sake of survival. In both cases, as well as in Inez’s story, religious repression triggered deep breaches in their selves.

Garcias’s time of exception lasts for more than seven years. When the Great Earthquake of 1755 destroys Lisbon, he does not follow the example of many prisoners who took the opportunity to flee. He stays, proving his constancy and wisdom, qualities which are awarded shortly after with release and freedom. The story ends with the arrival of Garcia and his family in England and their “return” to Judaism. After all, like Almah and Inez, Garcias was also a secret Jew, teaching his family “in accordance with the strictly orthodox principles of Catholicism” but covertly adhering “to the rigid essentials of the Jewish faith” in the same manner of “hundreds of other families.”47

Settlement in England gives Garcias the opportunity to break his secrecy and unmask his real beliefs.48 For Inez and Almah, England was also the place where they were allowed to take off all masks – the performed Christianity, the anomalous self-governance, the odd masculinization. In this sense, their stories perfectly embody the relation between gender and ethnicity as “intertwined categories of identity” that, according to Galchinsky, is characteristic of Aguilar’s work.49 Indeed, their arrival in London allows the three characters to perform a double return: to their ‘original Jewishness’ (after all, according to Aguilar, they were already Jews in Portugal, although in secret) and to their original gender roles as wives and mothers (Inez and Almah) or father and head of the family (Garcias). “The veil of secrecy was removed, they were in a land whose merciful and liberal government granted to the exile and the wanderer a home of peace and rest.”50 Through their stories, Aguilar praises England as “a home of security and freedom, such as they [Jews] then could never have even hoped to enjoy”, but also finds arguments to critique the “last relic of religious intolerance” in her time – legal discrimination in relation to other British subjects.51 By stressing Inez and Almah’s resilience, intelligence, and loyalty, but also their natural domesticity, only transgressed because of religious intolerance, Aguilar draws her characters closer to Christian readers, encouraging them to see Inez, Almah, and other Jewish women not as aliens but as English women, just like themselves.

The successful integration of Jews, in particular of the Sephardim, in English society is a key argument for Aguilar’s rationale for their acceptance as full citizens without having to renounce their Jewish faith. However, by the mid-nineteenth century, many Sephardim had already broken their ties with the Jewish community and converted to Christianity. This process was not so much a result of the efforts of the Protestant missionaries as the culmination of a process of progressive integration to the mainstream of English society through intermarriage, the mimicking of behaviours and lifestyles, and participation in non-Jewish social circles.52

The returnee

According to Todd Endelman, the “radical assimilation” of a number of Sephardim in England – whose numbers had no parallel in other European Jewish communities – should not be dissociated from their historical or even personal experience as conversos in Portugal and Spain, and the difficulties of the London Sephardic community in guiding them towards traditional Jewish life.53 Indeed, the failure to integrate converso newcomers into existing Jewish communities is a recurrent topic in the testimonies given by those who returned to Portugal from London and other communities of the Sephardi Diaspora.

Despite all the risks involved, the return to Portugal and Spain was undertaken by several individuals, as Yosef Kaplan has noted of those Jews who moved from Amsterdam to Iberia.54 These returnees were always considered as potentially subversive elements in the eyes of Inquisition. Their voluntary submission before the tribunal was an attempt to banish such suspicions, since, according to the regulations of the Inquisition, those who voluntarily confessed their faults and named their accomplices would be absolved after a formal abjuration, if the inquisitors considered their confession full and true and if they had had no previous denunciations levelled against them.55 Although these conditions were hard to fulfil, some returnees preferred to take the risk and submit themselves to the Inquisition’s procedures.

In this section, we will analyse a sample of testimonies from conversos or New Jews who returned to Portugal from London and which were submitted to the Inquisition between 1700 and 1760, a period that includes the great migratory wave to England of the 1720s and 1730s.

Inquisition trials are not the only sources that testify to this movement of returnees from England to Portugal. It is also possible to find evidence of this phenomenon in the correspondence of Portuguese diplomats in London. For instance, in May 1736, the envoy extraordinary Marco António de Azevedo Coutinho wrote about Samuel da Silva, a Jew from Amsterdam who had fled to London with the intention of going to Portugal and converting to Christianity. Although not entirely convinced of the young man’s honesty, Azevedo Coutinho was willing to give Silva aid to move to Portugal if he could ascertain the truth of his intentions.56 It was not a new situation for a Portuguese diplomat in London. Before Coutinho, the previous envoy extraordinary, António Galvão de Castelo-Branco, had hosted and provided means for the return of escapees to Portugal in the 1720s, when the numbers of Portuguese conversos to England reached its height. His support is reported in the confessions that some returnees gave to the Portuguese Inquisition, among them João Gomes Carvalho (1725), Francisco Ferreira Isidro (1728), and Gabriel Pereira de Sousa (1730), who used the provision of aid from a Portuguese diplomat as evidence of their willingness to return to Christianity.57

Inquisition trials of returnees from London

| Name | Arrival in London | Trial date | Reference* |

|---|---|---|---|

| João da Costa Varedo (Cadiz c. 1693 – London 1772) |

1712 |

1714 |

Lisbon, trial 7264 |

| Ângela Sanches (b. Lisbon c. 1677) |

1712 |

1716–17 |

Lisbon, trial 8689 |

| Diogo Moreno Franco (Crato c. 1681 – London 1726) |

1712 |

1716–17 |

Lisbon, trial 8207 |

| João Gomes Carvalho (Porto c. 1700 – London 1754) |

1723 |

1725–16 |

Lisbon, trial 8764 |

| Francisco Ferreira Isidro (b. Freixo de Espada-à-Cinta c. 1713) |

1727 |

1728 |

Lisbon, trial 4727 |

| Gabriel Pereira de Sousa (Faro c. 1702 – Barbados before 1740) |

1729 |

1730 |

Lisbon, trial 4408 |

| Gaspar Dias de Almeida (b. Celorico da Beira c. 1703) |

1730 |

1740–41 |

Lisbon, trial 9228 |

| Francisco Rodrigues da Costa (b. Chaves c. 1723) |

c. 1734 |

1757–58 |

Lisbon, trial 11727 |

| Gaspar Rodrigues da Costa (b. Lisbon c. 1731) |

1756 |

1757–58 |

Lisbon, trial 11731 |

| Manuel Henriques de Leão (b. Lisbon c. 1717) |

1756 |

1758 |

Lisbon, trial 1136 |

* Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Lisbon, Tribunal do Santo Ofício, Inquisition

This was not a unidirectional movement. Some of these returnees ended up leaving Portugal and Spain after sentencing by the Inquisition, returning once more to “lands of tolerance”. Such return caused serious concern among Jewish communities in the Diaspora, since these returnees had renounced the Jewish faith and formally reconverted to Christianity, thereby committing apostasy.58 It seemed clear that this situation had to be regulated. Therefore, from 1644, all Jews who had been in Portugal and Spain and returned to Amsterdam were obliged publicly to beg forgiveness before the community and undergo a period of penance before being readmitted as full members.59 The same policy was subsequently taken up in London.60 Indeed, the registers of the Mahamad (board of governors) of the London congregation record five individuals who had returned from Portugal and were subject to this penance during the first half of the eighteenth century: Raphael Rodrigues Dias, David Oróbio Furtado, and Moseh Rodrigues da Costa (all in 1733), Jacob Rodrigues Paulo (1734), and Isaac de Lara (1736).61 As can be seen from the Table here, none of these match the names of the returnees from London who were prosecuted by the Inquisition in the same period. The Mahamad records are, then, another valuable source for the study of this movement of return and “re-return”.

However, our analysis here will focus on the aforementioned confessions of returnees before the Inquisition. Instead of looking for the truth behind their words, we will consider them as receptor-focused narratives. After all, the major concern of the confessants was to appear credible, regardless of the truth or falsity of their testimonies. The events, reactions, and feelings that the returnees recounted were designed both to appear truthful and to meet with the Inquisition’s expectations. These narratives were constructed by combining the confessant’s experience, his understanding of the Inquisition’s expectations, and the desire to appear credible before the tribunal, so as to avoid torture and a harsh penalty. Thus, the returnees’ confessions tend to follow recurrent patterns. These are particularly noticeable in the justifications they give to explain both their departure to England and their return to Portugal.

By analysing Inquisition records related to Portuguese and Spanish returnees between 1580 and 1700, with a focus on those coming from France, David Graizbord determined some of the most frequent patterns. He distinguishes between two types of returnees: the habitual ones, who would travel to Portugal and Spain for temporary visits, and the permanents, whose intention was to resettle in the Iberian kingdoms. Graizord concludes that most of the returnees (in particular the permanent ones) justified their departure from Portugal or Spain with economic and social reasons, while non-economic motivations, such as difficulties of integration within the communities of the Diaspora or a religious awakening to Christianity, were more frequently mentioned to explain their return.62 A similar pattern is noticed in our sample of Inquisition records of returnees from England to Portugal. Indeed, most of these people indicated non-religious motivations for leaving Portugal, probably in order to make sure the Inquisition did not interpret their journey to England as a “confessional migration”.63 Poverty after release from inquisitorial prison or following the paterfamilias’s arrest and seizure of assets, unpaid debts and creditor’s harassment, expectations of support from relatives, or simply opportunities to make a living were reasons often given by confessants in order to justify their flight. For instance, João Varedo (or Baredo), a young man born in Cadiz, alleged that he went to England because he was poor, helpless, and without any means of livelihood.64

Extract from João da Costa Varedo’s Inquisition trial, 1714, in which he states that he had moved to England because he was poor, helpless, and without means of livelihood in Lisbon (lines 1–4). Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Tribunal do Santo Ofício, Inquisição de Lisboa, trial 7264, fol. 30. Courtesy of Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Lisbon

The fear of arrest by the Inquisition is less frequently cited as justification for leaving Portugal. Exceptions are heard from confessants who admitted to professing the Law of Moses while they were living in Portugal, as, for example, the merchant Gaspar Dias de Almeida, who fled on board an English vessel around 1730. On arrival in London he was circumcised and lived there as a Jew and later in Salé, Meknes, and Gibraltar. Almeida ended up confessing that his belief in the Law of Moses lasted until his presentation before the Inquisition and that he had returned to Portugal to conduct business affairs.65 Manuel Henriques de Leão, a merchant from Lisbon, also admitted Judaizing practices before his departure to London in 1756, but the major reason he alleged for his flight was not the harassment of the Inquisition but of his creditors. As he was deeply indebted, his voyage to London was only possible with the help of strangers. When he arrived in the city, Leão met the Jews who had funded his journey; this was his motivation for embracing the Law of Moses and consenting to circumcision.66

In the same way the returnees attempt to remove any suspicion that their journey to England was a confessional journey, they also try to give non-religious motivations to their integration into the Jewish community, by stressing their economic dependence on relatives and community leaders and members. Thus, they subscribe to the idea that bonds of solidarity and dependency between Jews and Iberian conversos were the cornerstone of the dissemination of Judaism in the Diaspora, ensuring the means of subsistence, protection, and social inclusion to the newcomers. On the one hand, this narrative strengthens their alleged willingness to return to Christianity – since by breaking these bonds, they put themselves in a precarious position – and, on the other hand, as it emphasizes community bonds over religious conviction, weakens their allegiance to Judaism.

However, downplaying this allegiance was harder for those who carried the physical mark of circumcision, an unequivocal proof of adherence to Judaism in the eyes of the Inquisition. Being aware that this mark would jeopardize the possibility of returning to Iberia, some exiles resisted being circumcised. This resistance concerned the Jewish community leaders, for whom circumcision was necessary in order to “remove the converso from his undefined situation”, and was also firm evidence of the convert’s desire to join the Jewish people.67 Responding to this situation, in 1727 the Mahamad of London imposed a deadline of fifteen days after arrival to those who came from Portugal and Spain to be circumcised, under penalty of losing the congregation’s assistance and being forced to repay their travel expenses.68

The circumcised who returned to Portugal or Spain had to provide the Inquisition with convincing explanations to justify such a clear mark of adherence to Judaism. These explanations, as well as the returnees’ descriptions of the ritual, conform to the image they wanted to give the tribunal of their former “Jewishness”. Gabriel Pereira de Sousa, who gave a detailed description of the ritual at his trial in 1730, ended up claiming that he only accepted it out of respect for his father’s authority and because he feared destitution if he refused.69 In his confession before the Inquisition in 1757, Francisco Rodrigues da Costa (alias David Rodrigues da Costa) explained that, a week after having arrived in London, his uncle António da Costa (alias Abraham da Costa) received in his house a group of six or seven Jewish men who “put a silk veil, named Talé, over his [Francisco’s] eyes, and circumcised him, giving him the name David as they recited some prayers.”70 Francisco was then an orphan aged eleven who was completely dependent on his uncle. His brother Gaspar Rodrigues da Costa (alias Joseph Rodrigues da Costa), who moved to London later in life, admitted more awareness of the ritual in his confession before the Inquisition in 1758. About a month after having arrived, a “so-and-so Payva” (Isaac Carrião de Paiba) circumcised him.71 Gaspar had been persuaded that the circumcision was crucial to ensure his stay in the city.72

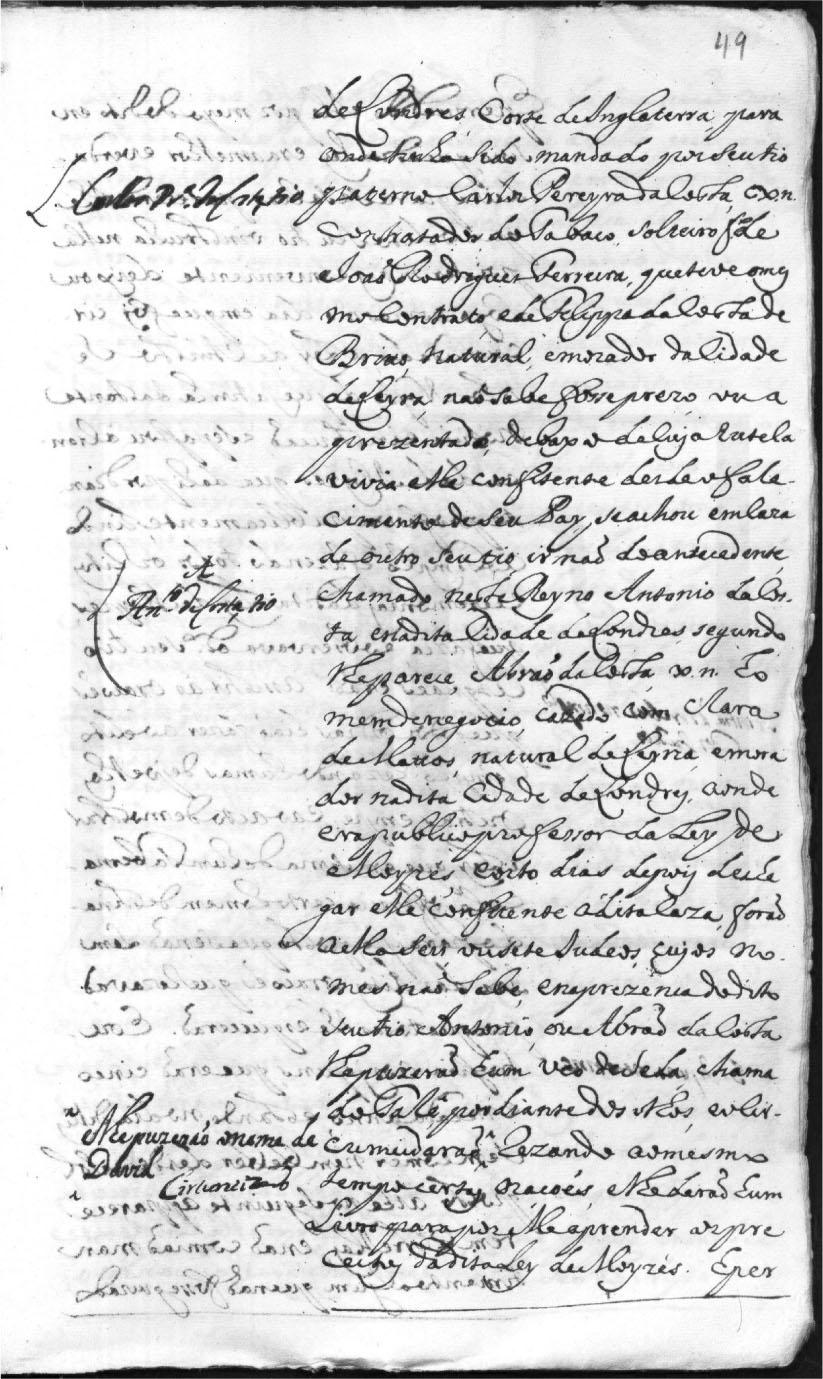

Extract from Francisco Rodrigues da Costa’s Inquisition trial, 1757–8, in which he recalls his circumcision in his uncle’s house in London (lines 20–27). Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Tribunal do Santo Ofício, Inquisição de Lisboa, trial 11727, fol. 49. Courtesy of Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Lisbon

Gaspar’s confessed to his circumcision only when the inquisitors subjected him to torture in April 1758. He had been imprisoned since November and, until then, had portrayed his experience within the Jewish community of London as marked by intimidation and fear. In his first statement to the Inquisition on 28 November 1757, Gaspar claimed that he had firmly defended the Christian faith during a stormy debate in a “Jewish college” (the Heshaim?) in London. Fearing retaliation, he moved to Amsterdam, where he continued to live as a Jew, which “was necessary to avoid the danger to which he was exposed, since it was said that the Jews of that city threw into the sea those who abandoned their Law.”73 To make matters worse, a letter was addressed to the congregation of Amsterdam, outlining the position that Gaspar had advocated during the said debate in London. The letter’s sender was Joseph Salvador (1716–1786), one of the wealthiest merchants of London, who served as parnas (warden) of the Bevis Marks congregation for a number of years.74

Francisco Ferreira Isidro also alluded to violent reactions against those exiles who refused to adhere to Judaism. During his time in London, he had heard that “certain Jews had already killed relatives and servants who did not want to follow their Law”, even mentioning the case of a Portuguese woman who supposedly killed her own daughter for refusing to attend the synagogue. Isidro used these examples to illustrate why he had attended the synagogue services, despite not having embraced the Jewish faith.75 As he strove to avoid circumcision, he felt obliged to leave his host’s home and seek refuge with the Portuguese envoy extraordinary in London.

Unawareness, dependency, economic need, coercion, and fear are the principal reasons given by these returnees to justify their circumcision or, at least, the observance of Jewish practices in the Diaspora. On the one hand, they portray their former selves as unwitting Jews or even fake Jews, thus reproducing centuries-old stereotypes that would be familiar to their target audience (the Inquisition) and, as a consequence, convincing. On the other hand, their picture of the Jewish communities as coercive, intolerant, and deeply anti-Christian institutions would also be easily recognizable to their audience, who saw in each Jew a harmful enemy of Christendom. In fact, such ideas of persecution and bigotry associated with the Jewish communities almost mirror the image of the Iberian inquisitions perpetuated by polemical writings, such as Geddes’s “Narrative”.

Similar accusations could be found in testimonies of Jewish converts to Christianity, in particular those of Sephardi extraction.76 The story of the young Dutch woman Eve Cohan, written by the Anglican bishop Gilbert Burnet, is a prime example. In the course of her conversion to Christianity, Eve was locked, beaten, and threatened with poisoning by her own mother. After marrying a Christian man and escaping to London, she fell victim to the machinations of a Jewish solicitor hired by her family, and was imprisoned. In jail, pregnant and subject to great distress, she miscarried her child.77 Eve Cohan’s story became popular in England and probably well-known among the Jews of London. That this or similar Jewish convert narratives common in Protestant polemical literature influenced the returnees’ testimonies is a hypothesis that should not be completely discarded, although there is no solid evidence to support it.

Another parallel is noticeable in the representation of the conversion to Christianity. In Cohan’s case, she had been introduced to the Christian religion by her music teacher, who took her to church and gave her a New Testament, whose reading “did first open her eyes”.78 Indeed, the religious awakening triggered by the reading and interpretation of the Sacred Scriptures is a prevailing topic both in Jewish convert narratives and in the returnees’ testimonies. Jens Åklundh defines it as a “Jewish non-Pauline conversion pattern”, that is, a conversion precipitated by biblical rationality rather than revelation.79 The explanation that the returnee Ângela Sanches gave to justify her reawakening to Christianity follows this pattern. In May 1716, she confessed before the Inquisition that she became aware of her “errors” (that is, her profession of Judaism) when she listened to her niece’s husband reading a passage of the Sacred Scriptures, in which, according to her, it was clear that Jesus Christ was the Messiah. Shortly after, she moved to Leghorn and met a Carmelite friar who “enlightened” her about the Christian faith. Ângela’s first confession was delivered before the Inquisition of Rome and annexed to her trial in the Inquisition of Lisbon. She and her sister Eugénia de Campos had arrived in Rome after a long journey that led them from Lisbon to Amsterdam, Bordeaux, Mons, Paris, London, and Leghorn, during which both sisters constantly switched their beliefs and religious practices between disclosure and concealment.80 Diogo Moreno Franco, a son-in-law of Eugénia de Campos, recalled in 1716–17 that his return journey to Christianity had begun in London, where he realised that the Jewish rites and interpretations of the Sacred Scriptures were not consistent.81

In short, there is a tendency among returnees to paint the reversion to Christianity as a reawakening to original faith, based on a thoughtful interpretation of the Sacred Scriptures (in a Christian key, of course), while their former experience as part of the Jewish community is generally portrayed as a sort of religious drift, conditioned by fear of retaliations, loss of protection, destitution, or even death. Accordingly, they strive to convince the Inquisition that their Jewish experience was a time of exception, a rupture with normality, but also a separation from God, a replacing of “true religion” by a capitulation to worldly concerns.

Conclusion, or a brief reflection on return

Just as Ângela Sanches, Diogo Moreno Franco, and several other former New Jews returned to Portugal and confessed their religious drift before the Inquisition, so Grace Aguilar portrays the return to the “true faith” of Almah Diaz and Inez Benito, although in their cases return moves in an opposite direction. Almah and Inez’s time of exception occurs when their relatively peaceful double life in Portugal is interrupted by the action of the Inquisition. Their previous masking of their Judaism had not been a shameful experience, but a proof of loyalty to God despite all adversity. Arriving in London and becoming part of a Jewish community meant returning to the true and now unveiled religion of their ancestors. The idealization of a religious continuity between the Portuguese and Spanish conversos and the Jews of the Diaspora, based on the idea of a secret Judaism maintained despite bigotry, allows Aguilar to trace a genealogical connection to medieval Iberian Jewry, when the Peninsula was the “home of the exiles”.82 After escaping from Portugal, Almah and Inez found another home in England. However, this “free and happy land”, where Jews could openly profess their inner beliefs, involved other problems at the time of Aguilar: Jewish people “are yet regarded as aliens and strangers; and still, unhappily too often, as objects of rooted prejudice and dislike.”83 The continuation of this prejudice makes the themes of a persecuting tribunal (the Inquisition) and a harassed people (the conversos in Portugal) not completely alien to her readers, allowing for comparisons to be made to contemporary issues, and raising awareness of the bias and social disadvantages that Jews in Victorian England still experienced. This comparative approach brings Aguilar’s narratives closer to her time, inscribing her work in an emergent cultural discourse that finds in the history of Iberian Jews and conversos a way to address contemporary national challenges.84

Aguilar’s goals differ profoundly from those that informed Geddes’s “Narrative”. He was an Anglican polemicist with a clear purpose in mind, that of criticizing the Inquisition. However, he too approaches the subject of return through a striking double perspective, reflecting a mismatch between the author’s objectives and the narrator/interlocutor’s experience. Geddes hopes that the Portuguese Jew will return to Christianity through conversion to the Anglican Church. His interlocutor does not conceive return in the same terms: he stresses his origins in “the Seed of Abraham” and claims that he can only be saved in the Law of Moses. For him, embracing Judaism in the Diaspora is returning to the path of salvation. For Geddes, the Jewish experience of his interlocutor is a time of exception caused by Popish bigotry, which drives conversos away from Christianity and aligns them with a Jewish redemptive discourse. He keeps to the hope that the wandering Portuguese “New Jew” can still be saved and redirected to the true religion.

In describing the potential Christianity of his interlocutor, Geddes’s speech comes closer to the returnees’ confessions before the Inquisition. Despite their different objectives, both are Christian discourses directed to a Christian audience, whether the Anglican reader or the inquisitor. In contrast, Aguilar voices a Jewish and diachronic view on the Diaspora phenomenon, maintaining a sense of belonging to an elite whose Iberian roots made it the heir of a superior cultural heritage, and using this to legitimize and empower the still stigmatized English Jews. However, and despite the opposite goals, Aguilar ends up sharing similar arguments and concepts with Geddes and the Portuguese returnees. For all of them, there was an original faith (professed, hidden, or inherited), a time of exception (the Jewish drift of Geddes’s interlocutor, the religious duality of the converso life of Aguilar’s characters, and the allegedly fake Judaism professed by the returnees), and the final return.

Indeed, all these narratives come together in the interpretation of conversion (whether to Christianity or Judaism) as a return and ultimately a reunion with the real religious self, a rediscovery of authentic roots.85