Introduction

In the early 1800s, democratic systems were established in various parts of North and South America, in Europe and Africa; by the end of the nineteenth century, such systems had been established in Asia. Although most of the first democracies were not consolidated or long-lasting, a steady increase in the number of democratic transitions signalled the coming era of democracy (Gurr et al., 1990; Fukuyama, 1992). Unsurprisingly, there has been a relatively recent increase in the curiosity of scholars, policymakers and the public alike about the main principles and characteristics of democracy, and the outcomes of democracy for citizens, especially in terms of the response of democracy in time of disasters.

This topic is crucial due to the significant variability of countries’ level of democratisation:

Many young democracies emerge in the presence of challenging initial conditions such as widespread poverty and inequality, economic dependence on a small range of commodities and high levels of ethnic fragmentation among other social divisions … initial conditions may also motivate politicians to centralize political and economic power, rather than distribute it more widely. (Kapstein and Converse, 2009: 2, xv)

It may be therefore puzzling to determine the trajectory of the development of democracy; particularly, many researchers and policymakers acknowledge unequal levels of countries’ democratisation across the world. Regardless of the global perception that democracy is the ultimate political system in terms of being the most beneficial to societal development, the lengthy history of democracy across countries stimulates scholars’ curiosity for its principles and outcomes (Tilly, 2007).

Some scholars believe that, even though there is no current alternative to democracy as a principle of legitimacy, democracy may stand unchallenged in principle and yet in practice be formidably challenged in its performance (Sartori, 1991: 247; Holbrook, 2008). Francis Fukuyama and Michael McFaul (2007) argue that the benefits of democracy and democratic coexistence significantly outweigh the costs, and hence that the spread of democracy should be promoted and not discouraged. However, it is uncertain whether the democratic system is more beneficial to societies than non-democracy in terms of people’s well-being, and, in particular, in its responsiveness to disaster.

It is with this understanding that we need ‘to seek theories that integrate both spheres, accounting for areas of enlargement between them’, as Robert Putnam (1988: 433) argues. Therefore, the first section of this article is devoted to the recent theoretical and empirical debates on definitions of democracy, democratic principles and progress. These include interpretations of the meaning of democracy, and an overview of the development and trajectory of its diffusion across the world. Such research is particularly pertinent to our understanding of a democratic system and its sustainability in the contemporary world. The second section of the article is concerned with the outcomes of democracy for societal well-being, which reflect democracy in practice – particularly, the responsiveness of democratic versus autocratic governments to their citizens in times of environmental challenges and disasters. This section includes notes on education on democracy, and the best pathways to education on democracy in a time of environmental disasters. The article concludes by highlighting the advantage of mechanisms and solutions of democracy in contrast to non-democracy to environmental challenges in times of disasters.

Understanding democracy and democratic processes

Democracy is an ancient political system that has existed for more than two millennia. Hence, over time, many scholars have analysed and reinterpreted the concept of democracy. Indeed, ‘the very fact that democracy has such a long history has contributed to confusion and disagreement, as “democracy” has meant different things for different people at different times and places’ (Dahl, 2000: 3). In general terms, democracy is a political system that should guarantee every adult citizen the right to vote. However, it is also supposed to protect ‘essential rights, general freedom, self-determination, moral autonomy, human development, … essential personal interests, political equality, peace-seeking, prosperity, and [provide] protection from tyranny’ (Dahl, 2000: 45). In terms of particular characteristics, democracies vary significantly. The differences range from the degree of openness of ruling elites to inclusion of all social groups within the governing body, to the scope and equality of guaranteed rights. Thus, many of the oldest societies that were generally considered to have had a consolidated democratic system were not always fully democratic (for example, France in the 1950s was viewed as a weakening democratic state with limited civil rights). In many consolidated Western liberal democracies, many citizens, including women and people from ethnic minorities, were excluded from the right to vote for decades. Women received the right to vote a hundred years after most of the oldest liberal democracies were established: in the United States in 1920, in Canada in 1918, in Britain in 1928, in France in 1945, and in the nearly two-hundred-year-old democracy of Costa Rica in 1936. (Incidentally, in stark contrast were the communist countries and authoritarian government of the Soviet Union, which granted equal rights to women from the time of the inception of the communist political system in 1921. These rights included the right to vote, and a quota system that guaranteed women election and representation in the top political offices as nearly one-third of members (Wejnert, 1996)). This disparity contradicts democracy’s concept of equality to all citizens (Markoff, 2003), and the fulfilment of the common desire of people to be recognised as equals (Tilly, 2007). The treatment of Albanian minorities in Serbia, and the Muslim population in Greece (Dinstein, 1992), as well as the persistent racial disparity in the United States, demonstrate the existence of other recent democracies that do not provide rights to minority citizens (Sigelman and Welch, 1991: 47–110).

Similarly, many scholars perceive newly democratised African countries as weak, not having unified ideological principles, and not embracing the concept of balance of power by their polity (Kissinger, 2001; Kapstein and Converse, 2009). In some of these democracies, the general laws and guiding principles of democratic rule are interpreted according to the ruling elite’s convenience, not democratic principles (Tilly, 2005), making the African democracies weakly democratic in practice (Prempeh, 2010: 19). Therefore, according to some academics, across periods of world history, ‘democracy disappeared in practice, remaining barely alive as an idea or a memory among a precious few’ (Dahl, 2000: 3).

Although many researchers and policymakers consider democracy to be the most beneficial system for societal development (Tilly, 2007), it may be puzzling to determine the main principles of democracy. Starting with the powerful work of Alexis de Tocqueville (2009) in the nineteenth century, through to modern analyses, examinations have incorporated theoretical investigations and pragmatic proposals concentrated on the characteristics of democracies. Led by analyses of the taxonomy of democratic models (Held, 1995) and the pre-requisites and definitions of democracy (Dahl, 1989, 1990, 2000), these examinations have addressed the required responsiveness of a democratic government to its citizens (Dowding et al., 2004). Part of governmental responsiveness is establishing foundations for citizens’ trust in governing institutions (Tilly, 2005). Noteworthy is the development of the rule of law (Rawls, 1999), and checks and balances that guard the ruling elite’s honesty and integrity (Kapstein and Converse, 2009). Citizens in democratic countries expect social justice and equal distribution of political rights and responsibilities (Dowding et al., 2004; Etzioni, 2004). They expect justice and fairness regarding the distribution of economic resources domestically (Kapstein and Converse, 2009: xix–xx) and globally (Wallerstein, 2001).

An essential component of democracy is also the inclusion of various groups of citizens in the governing process. The right to vote for all citizens is an essential part of democratic inclusiveness (Dahl, 1989, 2000). However, inclusive governance is also reflected by developed, vibrant civil society and participatory citizenship (Skocpol and Fiorina, 1999; Somers, 1993). Several scholars understand citizens’ participation and inclusion in the governing process as the prerequisites of democracy (for example, Dahl, 1989, 2000; Skocpol and Fiorina, 1999) and the backbone of democratic governance (Tilly, 2005, 2007).

Considering such breadth of principles critically desired by most societies, several scholars believe that an era dominated by the cultural values of independence, individuality, freedom, and the appreciation for individual achievement is inevitable, and marks the global prevalence of democracy (Fukuyama and McFaul, 2007; Inglehart and Welzel, 2005, 2009). The age of prosperity and human rights characterise countries’ future (Inglehart and Welzel, 2005, 2009). Unsurprisingly, following Hegel’s philosophy, scholars refer to a democratic system as the end of the world’s history (Fukuyama, 1992; Mandelbaum, 2004, 2008).

A contrasting perspective is expressed by scholars who study the outcomes of democracy, believing that modern liberal democracies are in crisis and are failing in their responsiveness to citizens. Hence, the time of worldwide democratisation is coming to an end, and democratic supremacy is being replaced by authoritarian rule that, like democracy, supports a global market economy, but that does not support freedom and individual rights (Gat et al., 2009; Kagan, 2008). One of the primary sources of the crisis of democracy is the world’s unequal economic development generated by marked globalisation and the dependency of the world system of low-developed on well-developed states (Wallerstein, 2001). Consequently, two interpretations of the content and meaning of a democratic system have prevailed: first, democracy is viewed as an ‘ideal’ imaginary model, where the system is assessed as it ought to be; second, it is viewed as an existing reality, where the system is assessed according to what exists – how democracy performs. Dahl (1989: 31) calls the first interpretation an ideal type or a ‘value judgment’, whereas the latter is an ‘empirical judgment’, assessed according to an existing reality.

Within this latter understanding, democracies vary regarding the degree of their inclusiveness, equality of rights, and equity of resource distribution across diverse groups of citizens within a particular country, making democracy not only a global, but also a national phenomenon. Accordingly, some countries may restrict responsiveness to citizens’ needs or concerns to a specific group of citizens, contrasting with a broad acceptance of citizens’ demands. In some democratic countries, citizens may be free to express their opinion or have access to a wide scope of resources, while other democracies may restrict access to selected groups of citizens. The national distinctions are particularly noticeable concerning the response of democracies to environmental disasters and environmental protection.

Since democracies vary, the many deviations of form and nature, oscillating between more and less democratic governments, are depicted by Held (1995) as models of democracy. Therefore, democracy as a political system is far from the uniform political structure that most academics refer to as an ideal type of democracy (Dahl, 1989: 31). Instead, democracy accounts for an existing reality. It is characterised by many deviations, and changing nature, vacillating between being more and less responsive to its citizens. Regardless of the prioritisation of different goals and principles, countries strive to obtain rule by the people and equal rights to their fullest extent. Democracy, therefore, rarely refers to an ‘ideal’ type of political system (Dahl, 2000: 3).

Democracy also is far from an orthodox trajectory. Most scholars use a democracy scale to evaluate the worldwide growth and strength of democracy, while accounting for the variability of democracy (Schwartzman, 1998). The scale allows the depiction of democratic fluctuation and its spread (Huntington, 1992), and the prediction of global diffusion of democracy (Wejnert, 2005, 2016). This article uses the democracy scale of 0–10 introduced by the Polity IV data set, and incorporated in a database Nations, Development and Democracy: 1800–2005 (Wejnert, 2007), and Polity IV data (Marshall, 2015) to illustrate the overall growth of democracies and the average level of countries’ democratisation (the strength of democracy).

The Polity IV data set is an 11-point scale developed by Jagger and Gurr (1995). It assesses level of democratisation using five indexes composed of major components of democracy: (1) competitiveness of political participation; (2) regulation of political participation; (3) competitiveness of executive recruitment; (4) openness of executive recruitment; and (5) constraints on chief executives. These five components are in keeping with the definition of political democracy as the extent to which the political power of elites is minimised and that of non-elites is maximised, which is similar to an ideal model of democracy assessed according to its principles rather than its performance (Dahl, 2000, 38). Moreover, the database assesses the level of democracy for each country per year, integrating socio-economic and political factors related to countries’ democratisation for 177 members of the international system (20 of which are historical, 157 of which are contemporary countries), from 1800 to 2005. To depict the most recent changes, the data are extended to 2015.

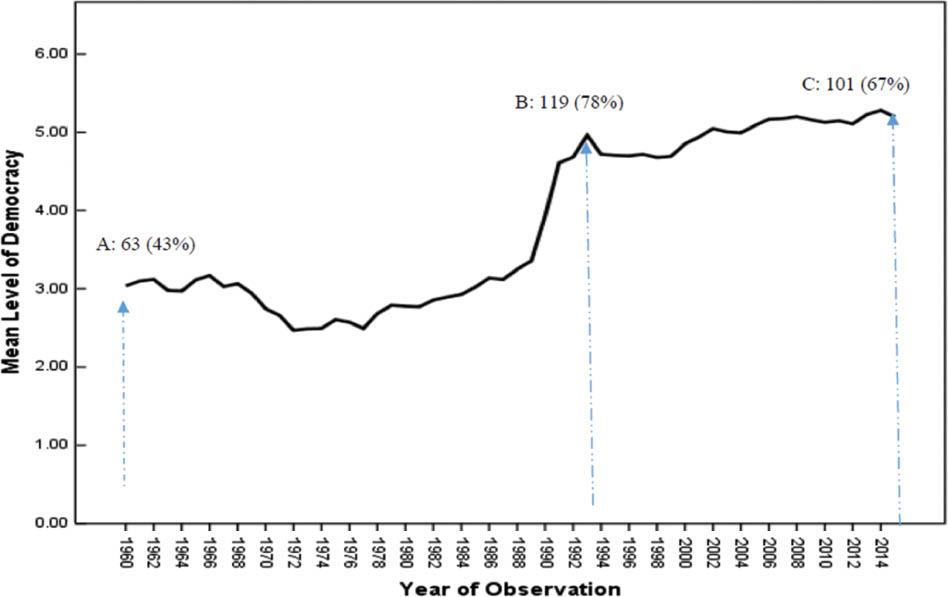

Figures 1 and 2 depict the progress of worldwide democratisation and the strength of democracy. They illustrate uneven but steady progress in worldwide democratisation across time.

Mean level of democracy across the world, 1800–2005 (Source: data adapted from Marshall and Gurr, 2017, and Wejnert, 2007). Note: Democracy level is assessed on a scale of 0–10, where 0 means non-democracy, and 10 means the top level of democracy on average in the world. Each year, the level of democracy is assessed only for sovereign countries. The study includes the 151 sovereign countries that have available data in the data sets used.

Mean level of democracy across the world, 1960–2016 (Source: data adapted from Marshall and Gurr, 2017, and Wejnert, 2007). Note: A, B, C = number of democracies and ratio of non-democratic countries in the world (percentage); ‘Democratic’ = democracy score larger than 0; ‘Non-democratic’ = score 0. See note for Figure 1.

Figure 2 also reveals that, regardless of the lengthy history of democracy, the average level of worldwide democratisation has weakened since 2008. This decline likely affects the responsiveness of democracies to citizens’ needs, especially during disasters.

Moreover, as shown in Figure 3, the average levels of democracy are uneven across the regions of Europe, Africa, Asia, the Middle East and the Americas. Figure 3 illustrates these differences in democracy level – the regional variance likely impacts the responsiveness of democracies in time of disasters.

Mean level of democracy across regions as compared to the worldwide democracy level, 1800–2005. Note: The number of countries in this figure varies across time in each region of the world.

The variability of the level of democracy over time, and the regional variance, makes this study on the outcome of democracy and its receptiveness to citizens’ needs in times of disasters and environmental challenges particularly intriguing and worth addressing. At the national level, consideration of diversity and variability of citizens within countries adds complexity to the problem.

Democracy in time of disaster and environmental challenges

One of the fundamental principles of democracy is its responsiveness to the emerging needs of citizens. As discussed above, these needs include the provision of economic equality, equal rights, protection of independent knowledge, and all citizens’/residents’ health. They also include environmental sustainability and mitigation of the impacts of disasters (Campbell and Pölzlbauer, 2010).

Research demonstrates that political institutions matter in terms of official policies, laws and regulations that aim to protect environmental sustainability, and to protect citizens in times of environmental disasters (Wilson, 2019). Democratic governments bear a particular responsibility for the mitigation of environmental degradation and disaster outcomes due to their principal goal of protecting citizens’ health and well-being, and guaranteeing environmental sustainability. However, scholarly debates are divided about whether democracies or autocracies are most suitable for the environment and provide the best response to citizens’ needs during environmental disasters. Dominant discussions fall into three sets of arguments (see Figure 4).

Role of political systems in creation of policies, laws and regulations to protect the environment and respond to disasters (Source: Author, 2021).

According to the first set of arguments, autocracies (that is, non-democracies) are better equipped to respond to environmental degradation and disasters. This popular claim by prominent environmentalists and economists, including William Ophuls (1977) and Paul Ehrlich (1968), prevailed in the 1970s. Scholars argue that autocracies, compared to democracies, provide a more robust response when societies exceed ‘limits of growth’, meaning that when societies overconsume, pollute the environment and procreate in an unlimited manner, autocracies can better mitigate excessive consumption and growth. Centralised power, authoritarian decision-making, and the imposition of control policies allow a fast and efficient governmental response to the ‘tragedy of the commons’, such as food scarcity or overpopulation (Hardin, 1968). In contrast, liberal democracies that stress individual liberty and do not impose control measures can potentially cause an ecological catastrophe.

As Garrett Hardin (1968) explains, resource use that is rational from the individual point of view leads to collective irrationality. When there is no limit on the use of available resources, members of a group take advantage of shared resources until the resources are exhausted. Coercion by mutual agreement can protect environmental resources from overuse, and coercion is more comfortably implemented in autocracies.

Moreover, Elizabeth Freedman et al. (2005: 216), studying Latin American countries, concluded that autocratic regimes often use environmental laws as a way of conceding to opponents of authoritarianism. Hence, environmental movements are more successful when they propose environmental policies jointly with other proposals. More recent environmental protection policies add that societies oriented towards economic growth leave environmental causes little chance to succeed when decision-making is democratic. The unlimited profit goals of private business prevent environmental protection measures in countries without centralised political power. Autocratic governments can impose regulations and taxes that curb consumption and pollution to offset businesses’ environmentally destructive practices and private consumption. In contrast, democratically elected decision-makers are concerned about their electorates and are less likely to impose limitations (Schweickart, 2010).

Finally, scholars argue that in autocracies society finds a way to avoid imposed regulations. Jessica Teets (2017), studying modern Chinese policymaking, argues that the autocratic government’s strict regulations can be altered by civil society, contradicting popular arguments that policymaking in authoritarian regimes lacks societal participation. The author demonstrates that, when China adopted strict regulations to control civil society by requiring registration of civil organisations with a supervisory agency, such organisations used the supervisory agency as an access point to policymakers, and successfully imposed changes in policies, including governmental response to environmental disasters.

According to the second set of arguments, authoritarian regimes rarely prioritise environmental conservation (Payne, 1995). Countries such as the Soviet Union, Putin’s Russia and Nazi Germany are labelled as environmental criminals (Laakonen et al., 2019). In contrast, a democratic system is most suitable for the environment (Winslow, 2005). Margrethe Winslow (2005) presents empirical evidence to support a relationship between democracy and one aspect of environmental quality: urban air pollution. She explores the relationship between environmental quality and democracy using a regression analysis of three pollutants’ urban air concentrations – sulphur dioxide (SO2), suspended particulate matter (SPM) and smoke – and two measures of democracy – the Freedom House Index and Polity III. The results suggest a significant and robust negative linear relationship between these pollutant concentrations and democracy level: the higher the level of democracy, the lower the ambient pollution level. Moreover, democracies are likely to learn from policy successes and failures in other democracies (Povitkina, 2018).

Consequently, scholars believe that democracy improves political measures on environmental outcomes and improves environmental protection by establishing protective laws and environmental regulations. These include limits on CO2 emission, clean water acts and residents’ protection during disasters (Freedman et al., 2005). Freedman et al. (2005) and Hochstetler (2003) studied Eastern European and Latin American environmental protection laws and the practices of new democracies compared to the autocratic period. The authors concluded that countries that have adopted democracy have better environmental protection practices and laws than authoritarian regimes. In communist Eastern Europe, governments designated one-third of land as pristine nature reserves and protected forests, and initiated control of water and air pollutant emissions. However, packets of highly polluted areas were mixed with successfully preserved nature. Also, the development of laws and regulations controlling pollution took place after the democratic transition. During the communist period, anti-pollution regulations were problematic; for example, Poland’s Silesian region and part of the Czech Republic were the most polluted parts of Europe. Notably, after the democratic transition, wealthier Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovenia and Estonia have a more robust rule of law and more vital environmental protection than poorer Eastern European countries.

According to these authors, the situation in Latin America is the same. National environmental agencies were initiated before democratisation; nonetheless, policies and laws were created and developed after the democratic transition. For example, in 1973, Brazil’s environmental agency had three employees, whereas, after the democratic transition, the number of employees had increased to 6,000 by the year 1989. In Chile, after the transition from military to civilian democratic government in 1990, the environmental agency increased personnel from 6 to 4,758, and its budget increased from $76,000 to $21 million by 2000 (Freedman et al., 2005).

Unsurprisingly, Robert Wilson (2019), in his volume Authoritarian Environmental Governance: Insights from the past century, argues that history helps us to better understand the possible social and environmental repercussions when democracy erodes, and environmental policies of authoritarian leaders proceed unchallenged. He argues that the most egregious examples of disastrous twentieth-century environmental governance were collectivisation campaigns in the communist Soviet Union, in China during the Mao period and in Nazi Germany. In the Soviet Union, 5 million farmers suffered severe famine (the so-called Holodomor), which caused the death of about 3.9 million of them. Agricultural production collapsed, and agricultural soil eroded. In China, rural Chinese people were forced to build thousands of backyard furnaces to melt farming equipment, cooking and eating implements, and other household items to forge steel. Predictably, nearly all the steel was useless, but peasants lost critical tools for farming and cooking food. By the end of Mao’s rule, and with the collapse of communism, Russian and Chinese state control, and the lack of political opposition that could control government activity, led to widespread environmental degradation and pollution resulting from the countries’ industrialisation.

Autocracies also do not reveal information about environmental disasters, endangering other countries, and often exacerbating the outcomes of disasters. The perfect example was the official secrecy, and the information withheld, by the communist government, about the 1986 Chernobyl disaster. During the disaster, 50 to 185 million curie radionuclides escaped into the atmosphere – seven times the amount of the radioactivity created by the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a figure that the Soviet regime sealed from disclosure. Furthermore, the Soviet regime released an official figure of 31 fatalities. In contrast, the Red Cross reported that hundreds of thousands of people died from radiation due to the accident (including from thyroid cancer; Alexievich, 2006). Similarly, the Soviet regime maintained secrecy about another nuclear accident in the Urals (Payne, 1995). Another example is the Chinese near three-month silence and falsehoods about the surge and rapid spread of the new coronavirus, COVID-19, which led to its worldwide spread. Within the first year, it claimed nearly a quarter of a billion lives, and a year and a half later, it continues to be uncontained.

Finally, the third set of arguments questions if the arbitrarily set binary categories of either beneficial or harmful responsiveness of democracies or autocracies to their citizens regarding environmental protection and disasters are empirically correct. Thus, Marina Povitkina (2018) asks whether democracies express more substantial commitments to climate change mitigation and, generally, emit less carbon dioxide than non-democratic regimes. Using a sample of 144 countries from 1970 to 2011, the author demonstrates that the corruption of democratic government determines the previously established relationship between the amount of a country’s CO2 emissions and the country’s level of democracy. Widespread corruption of democratic governments reduces the capacity of democratic governments to reach climate targets and reduce CO2 emissions. If corruption is high, democracies do not seem to do better than authoritarian regimes.

Similarly, Manus Midlarsky (1998) suggests a positive impact of democracy on the environment; however, the government’s responsiveness to environmental disasters requires reexamination. The responsiveness of democracies in times of disasters is not unidimensional in its relationship to the environment. Assessing the effect of democracy on three environmental indicators – deforestation, carbon dioxide emission and soil erosion by water – Midlarsky (1998) found that, contrary to prediction, the statistically significant effect of democracy on the environment was negative. Regarding protected land areas, the impact of democracy was positive. However, no significant effect of democracy on the environment was indicated regarding the impact on freshwater availability and soil erosion by chemicals. Meanwhile, authoritarian China is the largest emitter of CO2 in the world, and one of the greatest polluters. Nonetheless, it has also invested more than any other country in renewable energy to make a substantial effort to mitigate the effects of rapid industrialisation (Beeson, 2017).

At the national level, democracies and autocracies vary in terms of their responses to environmental challenges. Greater autonomy of local governments in democratic countries provides an opportunity for local environmental decision-making to question the policies of a central government. This practice is represented in current state governments’ debates on the Renewable Fuel Standards programme proposed by the Environmental Protection Agency of the US government (Bracmort, 2019).

Hence, nationally, the response of local government to environmental degradation and disasters varies between regions, and between city and rural environments. The response of elected policymakers at the local level of democratic government oscillates between being more and less responsive to environmental protection and environmental disaster mitigation policies, laws and practices. For example, Slavin (2011: 188) notes that former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced on Earth Day in 2007 the MillionTreesNYC Campaign, with the goal of planting a million trees by the year 2030, exemplifying the impact of local policymakers and regional variability within democratic countries regarding the mitigation of effects of environmental pollution. As mayor, Bloomberg increased energy efficiency and reduced New York City’s carbon footprint by 13 per cent. He helped make the city’s air the cleanest it had been in fifty years.

Congruently, the response of democracies to environmental disasters does not always accommodate environmental justice, and social inclusion in protecting all citizens, minority and majority alike. The 2020 Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health study, which showed that people who live in larger cities or areas with more air pollution faced higher risks of more severe illness or death from COVID-19 in the US, vividly exemplifies environmental justice problems within countries (Wu et al., 2020). Mustafa Santiago Ali, a former Environmental Protection Agency official in the US, talked about ‘sacrifice zones’ around the United States where communities of colour, people of low wealth, and Indigenous peoples are exposed to higher levels of pollution and have limited access to clean water, which contribute to chronic health problems. Environmental pollution, as the Harvard study shows, makes people more susceptible to COVID-19 (Ebbs, 2020). A similar effect of socio-economic disparities on variance in the response of democratic countries to mitigation of environment degradation can be seen with regard to building wind farms in England. According to a report by The Ecologist (2010), privileged social strata that have a more significant impact on policymaking hold back the creation of wind farms in their areas. Consequently, developers changed the planned location for new wind farm projects from the proposed prime sites in affluent communities to sites in deprived communities, not involving the local population in the planning ( The Ecologist, 2010).

Therefore, looking at the data on the effects of environmental disasters on local communities, Stacia Ryder (2017) proposes to include roots of social inequality in environmental solutions. Even though vulnerability to environmental disasters is discussed primarily in terms of environmental justice, the intersectional framework of addressing the roots of social inequality while focusing on environmental justice would lead to a better understanding of environmental harms and disaster vulnerabilities, argues Ryder (2017). Therefore, it will generate more just and equitable planning, preparedness, response and recovery activities. Such an intersection framework would account for citizens’ race, class (income), gender, ethnicity, disability and other inequalities. In his study on the interaction of global and national social inequality with the effectiveness of governmental response to environmental degradation Jeffrey Sachs (2015: 45–70) supports Ryder’s (2017) suggestion.

In contrast to democracies, non-compliance and debate with central government’s decisions is impossible in autocratic, strictly controlled regimes. Therefore, as shown above, and presented in the conclusion, autocracies are less responsive than democracies to environmental protection, mitigation of environmental challenges and citizens’ protection in times of disasters.

Education on democracy in a time of environmental disasters

Considering the variability of democratic principles and outcomes in societies across countries, and the complexity of the outcomes of democracy determined by social diversities nationally, starting with the groundbreaking work of John Dewey (1985) in 1916, several scholars claim the vital importance of education on democracy. Accordingly, schools at various levels of educational systems should be engaged in citizens’ education on democracy (see, for example, Doddington, 2018; Torres, 1998). As some researchers argue, since 2008, the crisis in democracies has generated scepticism about the need for education on democracy (for example, Pennington, 2014).

Jürgen Oelkers (2000: 15) has explained that education on democracy needs to focus on implementing and promoting principles of democracy while meeting education requirements – a practice where politics and education can be linked. Therefore, such education requires the development of critically thinking ‘citizens who can show solidarity not with the ruling class but with democracy, meaning the disputable exchange of arguments in the sphere of the political public bound to legitimate government’ (Oelkers, 2000: 16). ‘The virtue required here is called moral courage, and its characteristic is that it requires education’, writes Oelkers (2000: 16, emphasis in the original). Therefore, schools have an obligation to develop methods and concepts of education reflecting democratic principles and values simultaneously stimulating citizens’ engagement in governing and decision-making processes.

Concurring with Oelkers (2000: 16) that the decisive aspect of education is subject-related learning, where ‘knowledge and ability of third parties are translated into one’s own experience so that the standards are individualized’, this article claims that the principal goal of education on democracy in a time of environmental disasters is to form educated, socially engaged citizens who are innovative, critical thinkers and ecological problem solvers. Ideally, such an educational programme could incorporate experiential learning, hands-on experience in policymaking or creating green solutions (including nature-based solutions to environmental disasters), unconstrained debates, and participation in the development of sustainable pathways to share and care for public goods. Democracy as an inclusive system, respecting political freedom, is vital for these goals to be tenable.

Among the various forms of democratic education delineated by Edda Sant (2019), particularly applicable to proposed education on democracy in a time of environmental disasters, is deliberative democratic education (for example, Sabia, 2012; Biesta, 2011). It teaches future adult citizens to present and discuss environmental issues on public forums, especially when working on controversial topics. It also educates students to be publicly engaged contributors to national or local decision-making, de facto reducing the gap between citizens and policymakers.

Furthermore, deliberative education on democracy needs to incorporate a multicultural dimension of democratic education with its equality, inclusiveness and diversity, as proposed by Tim McDonough (2008) and Carlos Torres (1998). The goal of education is to account for social diversities within democracies (for example, gender, race, ethnicity and disability), and to combat modern challenges to a democratic system and the environment. As Torres (1998: 467) assures, democracy is a complex system, but it has survived because there is a space for debate and rules that people follow, even if they do not benefit. The commitment of schools and universities within democratic communities to expanding democratic discourse by embracing cultural diversity protects democracies from being at risk of weakening democratic principles, argues Torres (1998).

Concluding comments

As Wilson (2019) states, political institutions matter regarding environmental protection, and they matter in disasters. There are substantial differences in democracies’ and autocracies’ responsiveness to environmental disasters. Following Payne (1995), a six-point typology can summarise democracies’ compared to non-democracies’ responsiveness to disasters, and the relationship between democracy and the environment.

First, individual rights and an open marketplace of ideas allow the formation of public interest environmental groups. Democracy enables and encourages the development of civil society and participatory citizenship; believing that diversity of opinions strengthens democracy, democratic governments do not obstruct or imprison dissidents and ban their protests (Skocpol and Fiorina, 1999). Therefore, environmental groups can lobby and push democratic governments to pass environmental legislation. In contrast, autocracies do not allow peaceful protests or the formation of civil society, inhibiting citizens’ impact on environmental laws and regulations.

Second, democratic regimes are responsive to voters. Voters elect and vote out legislators. Participatory decision-making of both state and citizens allows participants to educate each other through reasoned arguments and reflections, media campaigns, promotions of new policies, and environmental safety campaigns (Meadowcroft, 2004). Collective long-term interest, rather than short-term individual interest, dominates democratic politics (Dryzek, 1997; Fischer, 2000). Consequently, in democracies citizens’ needs and well-being are the points of reference for governmental response to disasters. Democracies prioritise providing relief to communities and individuals during and after disasters to rebuild citizens’ livelihood, regardless of citizens’ affluence or sociopolitical conviction. The crucial role includes: (1) preparation for a potential environmental disaster and challenges; (2) response to disasters; and (3) recovery from disasters to provide future individual and community development. Democratic governments respond via the lens of human needs, finding immediate and long-term solutions to environmental problems.

Third, democracies network with other democratic countries, and they are more responsive to international environmental pressure. Through networking, democracies learn from policy successes and failures in other democracies. Similarly, international networks of scientists and scholars put global pressure on democratic governments to accept environmental policies.

Fourth, democracies traditionally support international organisations, believing that global networking and cooperation among nations solves global problems, including climate and environmental degradation.

Fifth, democracies support the open market economy. Markets typically try to avoid environmental regulations to gain additional profit, often limitlessly exploiting the environment. Nonetheless, the economies of autocracies have equally exploited the environment, as shown by the devastating environmental impact of Chinese and eastern European centrally controlled economies. The difference lies in the power of green consumers oriented towards environmental protection. In democracies that respect freedom of speech and assembly, the market can protect the environment if green consumers (consumers oriented for the conservation of the environment) demand environmentally sound products, reshaping environmental policies. In contrast, they are unable to affect policies in autocracies.

Sixth, the most striking contrast is democratic versus autocratic governments’ response to environmental disasters. In democracies such as the US, when a disaster is declared, the Federal government, led by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), respond to the request for help, providing financial and other emergency relief to support communities impacted by a disaster. The relief is organised under the National Response Framework. It focuses not only on immediate safety secured by the relocation of the affected population, but also on restoring, redeveloping and revitalising communities impacted by environmental emergencies. The assistance to communities and recovery often begins while emergency response activities are still in progress, helping communities and individuals to recover faster and more robustly than they could on their own.

In contrast, autocracies focus on preserving the state’s image and strength first, and help for individuals and communities comes second. For instance, the communist government attempted to cover up the explosion of a nuclear reactor during the Chernobyl disaster. It only admitted that the accident had occurred when the radioactive cloud was detected in Sweden two days after the explosion. It took two weeks to contain the fire and the radioactivity leaking from the main reactor, exposing local and international communities to radioactive emissions. Nearly a decade and a half later, communities continued to have many health problems linked to the Chernobyl disaster (genetic mutations, cancer, diabetes; Gray, 2019). In addition to the effects on the population’s health, equally disastrous was the effect of the accident on the natural environment. Since the explosion, nearly 57,915 square miles of Belarus, Russia and Ukraine are contaminated, and the 4,000 km2 (1,544 square miles) exclusion zone remains uninhabited decades after the explosion. The radioactive fallout, carried by winds, scattered over much of the northern hemisphere. Pollution of plants and grasslands in Britain led to the severely restricted sale of lamb and other sheep products for many years (Alexievich, 2006: 196).

Similarly, in 2019 in China, natural disasters affected 130 million people, with 766 killed, 103 people missing, and 4.96 million evacuated or relocated. Floods, typhoons, droughts, earthquakes and landslides caused direct economic losses of 306.32 billion yuan (about US$43.31 billion). The Chinese government’s response focuses on emergency management, creating emergency management committees that include local Communist Party officials, government and military officials. The committees’ response to environmental disasters concerns resettlement and relocation of individuals and communities affected by the disasters. Specifically, in 2007, the Chinese government adopted and enacted the Emergency Response Law. The purpose of the law is to prevent and reduce the occurrence of emergencies. It also aims to control, mitigate and eliminate the severe social harm caused by environmental disasters. The law regulates activities in response to emergencies and protects the lives and property of the people, national security, public security and environmental safety. However, a vital part of the Emergency Response Law is maintaining public order in disasters; providing financial or other relief to individuals to rebuild their livelihood is not included in the response packet.

The distinction between the response of democracies and non-democracies during disasters and other environmental challenges is striking when considering citizens’ well-being and livelihood. The differences rest on principles of democracy that affect environmental policies. Democracies give more prominent political roles to ordinary citizens, provide and secure broad access to decision-making, offer free media information and access to media, and focus on well-being and rebuilding individual lives and communities. On the other hand, autocracies rely on centralised leadership and centralised decision-making, prioritising states’ benefits, strength and image. Consistent with the priorities of democracies and non-democracies is the subsequent education of citizens regarding their role in the mitigation of effects of environmental disasters and response to environmental challenges. Unlike in democracies, where developing education is open for debate and public participation in the decision-making process, education in autocracies focuses on conformity, limiting individual innovativeness (for example, Zhao, 2014). Undoubtedly, therefore, responding to the challenges of environmental disasters and citizens’ education about a response to environmental disasters, the democratic political system offers advantageous mechanisms and solutions in contrast to non-democracy.