Introduction

Coronary spasm plays an important part not only in the pathogenesis of variant angina (VA) but also in ischemic disease generally, including resting and effort angina, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and sudden death [1, 2]. In approximately one in ten patients with AMI, angiography does not reveal any obstructive coronary artery disease.

VA is characterized by chest pain that is not related to exercise, and is frequently accompanied by transient ST segment elevation on ECG [3]. The patient is symptom-free with normal ECG findings during the symptom-free periods [4]. Although the underlying mechanism is not well understood, it appears to involve a combination of endothelial damage and vasoactive mediators. In this case, a 58-year-old man with myocardial infarction secondary to coronary artery vasospasm experienced recurrent chest pain and had a noncritical lesion as revealed by a normal coronary angiogram.

Case Report

We report the case of a 58-year-old man with coronary artery disease, hypertension, and an 11-month history of percutaneous coronary intervention (the first percutaneous coronary intervention) with a rapamycin-eluting stent (second-generation Firebird stent, MicroPort, Shanghai, China) from the left main (LM) artery to the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery. He was admitted to our department because of chest pain and loss of consciousness at rest. The patient was hospitalized for further evaluation. Repeated ECG showed T wave inversions in body leads II, III, and avF and chest leads V5 and V6 (Figure 1), There was a significant increase in troponin I levels (36.9 ng/mL [0–0.034 ng/mL is normal level of troponin]). Acute coronary syndrome was diagnosed and medical management was initiated.

Patient’s ECG at Admission.

ECG showing T wave inversions in body leads II, III, and avF and chest leads V5 and V6.

The next day the patient reported similar symptoms at 10 a.m. and 3 p.m. ECG showed ST segment elevation in body leads II, III, and avF with elevated troponin T level, the heart rate was 70/min, and the blood pressure was 101/56 mmHg. The patient’s chest pain was resolved immediately by use of nitroglycerin. The symptoms lasted for less than 7 min, after which the vital signs returned to normal (the second time the symptoms lasted for 2 min). Repeated ECG was done after 7 min and showed thorough absence of the ST changes (Figure 2). Echocardiography showed motion abnormalities of the left ventricular wall and posterior wall, and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 55% (Supplementary Figure 1). The patient remained asymptomatic for the rest of the day with the same baseline ECG readings.

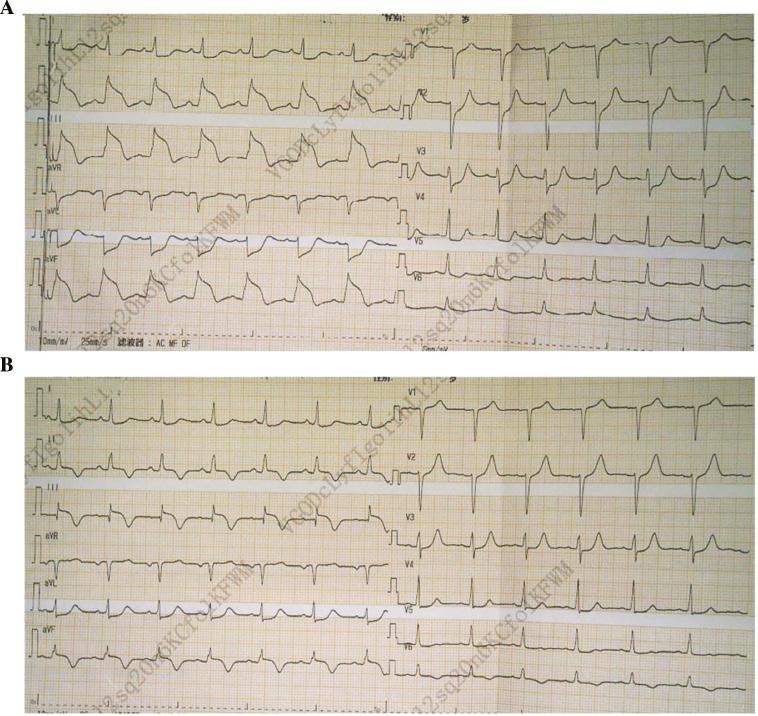

ECG of Patient with Angina and Remission.

(A) ECG showing ST segment elevation in body leads II, III, and avF with elevated troponin T level. (B) ECG showing thorough absence of the ST changes.

The patient underwent coronary catheterization, which demonstrated no in-stent restenosis in the LM artery and the proximal LAD artery; that is to say, the previously implanted blood flow, we found another thing: a 60% spasm in the first segment of right coronary artery, which was promptly relieved by intracoronary administration of isosorbide dinitrate (Figure 3). The ECG before and after the spasm relieved by intracoronary administration of isosorbide dinitrate are shown in Figure 4. Accordingly, the patient was discharged home with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, diltiazem, clopidogrel, and a statin as medication, and at the 2-month follow-up, he was free of symptoms and had not experienced chest pain at rest or during effort.

Discussion

The first case of VA was described in 1959 by Prinzmetal et al. [5]. VA is characterized by chest pain secondary to reversible coronary artery vasospasm in the context of both diseased and nondiseased coronary arteries. The precise mechanism for VA has not been elucidated, but essential findings have been made regarding its pathophysiology.

There are different contributors to the regulation of vascular spasm. Among them, endothelium dysfunction plays an important part. It is characterized by impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxation with reduced levels of endothelial nitric oxide synthase secondary to nitric oxide bioavailability. Hypercontractility of vascular smooth muscle cells is also involved [6]. Recent findings at the gene level linked it to a biochemical disorder with increased activity of a small GTPase [7]. Calcium channel blockers (CCBs), long-acting nitrates, Rho-kinase inhibitor, and nicorandil are used to treat coronary artery spasm.

The VA hallmark feature is rest angina. In VA, attacks usually occur between midnight and the early morning and lead to a transient ST segment elevation on ECG [8]. The autonomic nervous system is an important regulator of ischemic episodes of VA. Ischemic episodes with transient ST segment elevation at 10 a.m. and 3 p.m. were seen in our patient. This is not the same time as traditional VA attacks, which is also a novel aspect of our case. Some studies have reported acute modifications of the autonomic nervous system activity in patients with VA with sympathovagal imbalance minutes before an attack occurs [9]. The times and the reasons the classic VA occurs are as follows: the attack occurs when the patient wakes up for minutes in the morning or at noon, which are the sympathovagal alternation minutes, prone to sympathovagal imbalance.

Coronary artery vasospasm is a recognized cause of VA that can have various clinical forms, such as myocardial infarction, ventricular arrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death. Our patient had AMI secondary to VA. It is very challenging to diagnose cases of VA, especially because the ECG usually normalizes a few minutes after symptom resolution. Sudden relief of angina on treatment with nitroglycerin reveals coronary artery spasm and can be used to diagnose VA without the need to perform coronary angiography. Our patient had ST segment elevation during chest pain that resolved immediately with use of nitroglycerin. When chest pain reoccurred, there was no further increase in the troponin T level. The coronary angiogram showed a noncritical lesion.

In our case, we have a bitter lesson. Eleven months previously, the patient underwent the first percutaneous coronary intervention, where the surgical strategy was as follows: Firstly, the plaque in the walls of the LM artery and the LAD artery was unstable and a stent was implanted. Secondly, the stenosis rate was insufficient for implantation of a stent in the right coronary artery. The patient was given nicorandil after discharge. Failure to prevent coronary spasm eventually led to myocardial infarction. The patient experienced chest pain accompanied by ST segment elevation in body leads II, III, and avF at home. The patient was admitted to our department and treated with diltiazem; he did not have an additional episode of VA during 3months of follow-up.

In our case, the patient was treated with diltiazem. Diltiazem is a non-dihydropyridine CCB. CCBs seem to be the first-line therapy for VA. Nitrates were also found to be efficient therapy. Clinical trials have revealed that patients who received diltiazem have better outcomes than patients treated with other medical therapy [10]. Diltiazem inhibits mainly L-type calcium channels. Diltiazem can reduce arterial wall injury caused by calcium overload, inhibit smooth muscle proliferation and arterial matrix protein synthesis, increase vascular compliance, inhibit lipid peroxidation, and protect endothelial cells [11].

Conclusion

Our case provides information about the treatment with diltiazem of patients with AMI secondary to VA. VA can be life-threatening. Since our patient positively responded to the therapy, he was followed up without further intervention. He did not have an additional episode of VA during 3months of follow-up.