- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Delay or Avoidance of Medical Care Because of COVID-19–Related Concerns — United States, June 2020

research-article

Mark É. Czeisler

1

,

2 ,

Kristy Marynak , MPP

3

,

4

,

,

Kristie E.N. Clarke , MD

3 ,

Zainab Salah , MPH

3 ,

Iju Shakya , MPH

3 ,

JoAnn M. Thierry , PhD

3 ,

Nida Ali , PhD

3 ,

Hannah McMillan , MPH

3 ,

Joshua F. Wiley , PhD

1 ,

Matthew D. Weaver , PhD

1

,

5

,

6 ,

Charles A. Czeisler , PhD, MD

1

,

5

,

6 ,

Shantha M.W. Rajaratnam , PhD

1

,

2

,

5

,

6 ,

Mark E. Howard , MBBS, PhD

1

,

2

,

7

11 September 2020

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

Temporary disruptions in routine and nonemergency medical care access and delivery

have been observed during periods of considerable community transmission of SARS-CoV-2,

the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (

1

). However, medical care delay or avoidance might increase morbidity and mortality

risk associated with treatable and preventable health conditions and might contribute

to reported excess deaths directly or indirectly related to COVID-19 (

2

). To assess delay or avoidance of urgent or emergency and routine medical care because

of concerns about COVID-19, a web-based survey was administered by Qualtrics, LLC,

during June 24–30, 2020, to a nationwide representative sample of U.S. adults aged

≥18 years. Overall, an estimated 40.9% of U.S. adults have avoided medical care during

the pandemic because of concerns about COVID-19, including 12.0% who avoided urgent

or emergency care and 31.5% who avoided routine care. The estimated prevalence of

urgent or emergency care avoidance was significantly higher among the following groups:

unpaid caregivers for adults* versus noncaregivers (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR] = 2.9);

persons with two or more selected underlying medical conditions

†

versus those without those conditions (aPR = 1.9); persons with health insurance versus

those without health insurance (aPR = 1.8); non-Hispanic Black (Black) adults (aPR = 1.6)

and Hispanic or Latino (Hispanic) adults (aPR = 1.5) versus non-Hispanic White (White)

adults; young adults aged 18–24 years versus adults aged 25–44 years (aPR = 1.5);

and persons with disabilities

§

versus those without disabilities (aPR = 1.3). Given this widespread reporting of

medical care avoidance because of COVID-19 concerns, especially among persons at increased

risk for severe COVID-19, urgent efforts are warranted to ensure delivery of services

that, if deferred, could result in patient harm. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic,

persons experiencing a medical emergency should seek and be provided care without

delay (

3

).

During June 24–30, 2020, a total of 5,412 (54.7%) of 9,896 eligible adults

¶

completed web-based COVID-19 Outbreak Public Evaluation Initiative surveys administered

by Qualtrics, LLC.** The Human Research Ethics Committee of Monash University (Melbourne,

Australia) reviewed and approved the study protocol on human subjects research. This

activity was also reviewed by CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal

law and CDC policy.

††

Respondents were informed of the study purposes and provided electronic consent before

commencement, and investigators received anonymized responses. The 5,412 participants

included 3,683 (68.1%) first-time respondents and 1,729 (31.9%) persons who had completed

a related survey

§§

during April 2–8, 2020. Among the 5,412 participants, 4,975 (91.9%) provided complete

data for all variables in this analysis. Quota sampling and survey weighting

¶¶

were employed to improve cohort representativeness of the U.S. population by gender,

age, and race/ethnicity.

Respondents were asked “Have you delayed or avoided medical care due to concerns related

to COVID-19?” Delay or avoidance was evaluated for emergency (e.g., care for immediate

life-threatening conditions), urgent (e.g., care for immediate non–life-threatening

conditions), and routine (e.g., annual check-ups) medical care. Given the potential

for variation in interpretation of whether conditions were life-threatening, responses

for urgent and emergency care delay or avoidance were combined for analysis. Covariates

included gender; age; race/ethnicity; disability status; presence of one or more selected

underlying medical conditions known to increase risk for severe COVID-19; education;

essential worker status***; unpaid adult caregiver status; U.S. census region; urban/rural

classification

†††

; health insurance status; whether respondents knew someone who had received a positive

SARS-CoV-2 test result or had died from COVID-19; and whether the respondents believed

they were at high risk for severe COVID-19. Comparisons within all these subgroups

were evaluated using multivariable Poisson regression models

§§§

with robust standard errors to estimate prevalence ratios adjusted for all covariates,

95% confidence intervals, and p-values to evaluate statistical significance (α = 0.05)

using the R survey package (version 3.29) and R software (version 4.0.2; The R Foundation).

As of June 30, 2020, among 4,975 U.S. adult respondents, 40.9% reported having delayed

or avoided any medical care, including urgent or emergency care (12.0%) and routine

care (31.5%), because of concerns about COVID-19 (Table 1). Groups of persons among

whom urgent or emergency care avoidance exceeded 20% and among whom any care avoidance

exceeded 50% included adults aged 18–24 years (30.9% for urgent or emergency care;

57.2% for any care), unpaid caregivers for adults (29.8%; 64.3%), Hispanic adults

(24.6%; 55.5%), persons with disabilities (22.8%; 60.3%), persons with two or more

selected underlying medical conditions (22.7%; 54.7%), and students (22.7%; 50.3%).

One in four unpaid caregivers reported caring for adults who were at increased risk

for severe COVID-19.

TABLE 1

Estimated prevalence of delay or avoidance of medical care because of concerns related

to COVID-19, by type of care and respondent characteristics — United States, June

30, 2020

Characteristic

No. (%)†

Type of medical care delayed or avoided*

Urgent or emergency

Routine

Any

%†

P-value§

%†

P-value§

%†

P-value§

All respondents

4,975 (100)

12.0

—

31.5

—

40.9

—

Gender

Female

2,528 (50.8)

11.7

0.598

35.8

<0.001

44.9

<0.001

Male

2,447 (49.2)

12.3

27.0

36.7

Age group, yrs

18–24

650 (13.1)

30.9

<0.001

29.6

0.072

57.2

<0.001

25–44

1,740 (35.0)

14.9

34.2

44.8

45–64

1,727 (34.7)

5.7

30.0

34.5

≥65

858 (17.3)

4.4

30.3

33.5

Race/Ethnicity

White, non-Hispanic

3,168 (63.7)

6.7

<0.001

30.9

0.020

36.2

<0.001

Black, non-Hispanic

607 (12.2)

23.3

29.7

48.1

Asian, non-Hispanic

238 (4.8)

8.6

31.3

37.7

Other race or multiple races, non-Hispanic¶

150 (3.0)

15.5

23.9

37.3

Hispanic, any race or races

813 (16.3)

24.6

36.4

55.5

Disability**

Yes

1,108 (22.3)

22.8

<0.001

42.9

<0.001

60.3

<0.001

No

3,867 (77.7)

8.9

28.2

35.3

Underlying medical condition††

No

2,537 (51.0)

8.2

<0.001

27.9

<0.001

34.7

<0.001

One

1,328 (26.7)

10.4

33.0

41.2

Two or more

1,110 (22.3)

22.7

37.7

54.7

2019 household income, USD

<25,000

665 (13.4)

13.9

0.416

31.2

0.554

42.8

0.454

25,000–49,999

1,038 (20.9)

11.1

30.9

38.6

50,000–99,999

1,720 (34.6)

12.5

30.5

41.1

≥100,000

1,552 (31.2)

11.2

33.0

41.4

Education

Less than high school diploma

65 (1.3)

15.6

0.442

24.7

0.019

37.9

0.170

High school diploma

833 (16.7)

12.3

28.1

38.1

Some college

1,302 (26.2)

13.6

29.7

40.3

Bachelor's degree

1,755 (35.3)

11.2

34.8

43.6

Professional degree

1,020 (20.5)

10.9

31.2

39.5

Employment status

Employed

3,049 (61.3)

14.6

<0.001

31.5

0.407

43.3

<0.001

Unemployed

630 (12.7)

8.7

34.4

39.5

Retired

1,129 (22.7)

5.3

29.9

33.8

Student

166 (3.3)

22.7

30.5

50.3

Essential worker status§§

Essential worker

1,707 (34.3)

19.5

<0.001

32.4

0.293

48.0

<0.001

Nonessential worker

1,342 (27.0)

8.4

30.3

37.3

Unpaid caregiver status¶¶

Unpaid caregiver for adults

1,344 (27.0)

29.8

<0.001

41.0

<0.001

64.3

<0.001

Not unpaid caregiver for adults

3,631 (73.0)

5.4

27.9

32.2

U.S. Census region***

Northeast

1,122 (22.6)

11.0

0.008

33.9

0.203

42.5

0.460

Midwest

936 (18.8)

8.5

32.0

38.7

South

1,736 (34.9)

13.9

29.6

40.7

West

1,181 (23.7)

13.0

31.5

41.5

Rural/Urban classification†††

Urban

4,411 (88.7)

12.3

0.103

31.5

0.763

41.2

0.216

Rural

564 (11.3)

9.4

30.9

38.2

Health insurance status

Yes

4,577 (92.0)

12.4

0.036

32.6

<0.001

42.3

<0.001

No

398 (8.0)

7.8

18.4

24.8

Know someone with positive test results for SARS-CoV-2§§§

Yes

989 (19.9)

8.8

0.004

40.7

<0.001

46.6

<0.001

No

3,986 (80.1)

12.8

29.2

39.5

Knew someone who died from COVID-19

Yes

364 (7.3)

10.1

0.348

41.4

<0.001

46.3

0.048

No

4,611 (92.7)

12.2

30.7

40.5

Believed to be in group at high risk for severe COVID-19

Yes

981 (19.7)

10.0

0.050

42.5

<0.001

49.4

<0.001

No

3,994 (80.3)

12.5

28.8

38.8

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; USD = U.S.

dollars.

* The types of medical care avoidance are not mutually exclusive; respondents had

the option to indicate that they had delayed or avoided more than one type of medical

care (i.e., routine medical care and urgent/emergency medical care).

† Statistical raking and weight trimming were employed to improve the cross-sectional

June cohort representativeness of the U.S. population by gender, age, and race/ethnicity

according to the 2010 U.S. Census.

§ The Rao-Scott adjusted Pearson chi-squared test was used to test for differences

in observed and expected frequencies among groups by characteristic for avoidance

of each type of medical care (e.g., whether avoidance of routine medical care differs

significantly by gender). Statistical significance was evaluated at a threshold of

α = 0.05.

¶ “Other” race includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific

Islander, or Other.

** Persons who had a disability were defined as such based on a qualifying response

to either one of two questions: “Are you limited in any way in any activities because

of physical, mental, or emotional condition?” and “Do you have any health conditions

that require you to use special equipment, such as a cane, wheelchair, special bed,

or special telephone?” https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdf-ques/2015-brfss-questionnaire-12-29-14.pdf.

†† Selected underlying medical conditions known to increase the risk for severe COVID-19

included in this analysis were obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiovascular

disease, and any type of cancer. Obesity is defined as body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 and

was calculated from self-reported height and weight (https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html).

The remaining conditions were assessed using the question “Have you ever been diagnosed

with any of the following conditions?” with response options of 1) “Never”; 2) “Yes,

I have in the past, but don’t have it now”; 3) “Yes I have, but I do not regularly

take medications or receive treatment”; and 4) “Yes I have, and I am regularly taking

medications or receiving treatment.” Respondents who answered that they have been

diagnosed and chose either response 3 or 4 were considered as having the specified

medical condition.

§§ Essential worker status was self-reported.

¶¶ Unpaid caregiver status was self-reported. Unpaid caregivers for adults were defined

as having provided unpaid care to a relative or friend aged ≥18 years at any time

in the last 3 months. Examples provided to survey respondents included helping with

personal needs, household chores, health care tasks, managing a person’s finances,

taking them to a doctor’s appointment, arranging for outside services, and visiting

regularly to see how they are doing.

*** Region classification was determined by using the U.S. Census Bureau’s Census

Regions and Divisions. https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf.

††† Rural-urban classification was determined by using self-reported ZIP codes according

to the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy definition of rurality. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/definition/datafiles.html.

§§§ For this question, respondents were asked to select the following statement, if

applicable: “I know someone who has tested positive for COVID-19.”

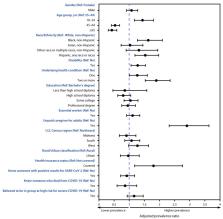

In the multivariable Poisson regression models, differences within groups were observed

for urgent or emergency care avoidance (Figure) and any care avoidance (Table 2).

Adjusted prevalence of urgent or emergency care avoidance was significantly higher

among unpaid caregivers for adults versus noncaregivers (2.9; 2.3–3.6); persons with

two or more selected underlying medical conditions versus those without those conditions

(1.9; 1.5–2.4); persons with health insurance versus those without health insurance

(1.8; 1.2–2.8); Black adults (1.6; 1.3–2.1) and Hispanic adults (1.5; 1.2–2.0) versus

White adults; young adults aged 18–24 years versus adults aged 25–44 years (1.5; 1.2–1.8);

and persons with disabilities versus those without disabilities (1.3; 1.1–1.5). Avoidance

of urgent or emergency care was significantly lower among adults aged ≥45 years than

among younger adults.

FIGURE

Adjusted prevalence ratios*

,

†

for characteristics

§

,

¶

,

**

,

††

associated with delay or avoidance of urgent or emergency medical care because of

concerns related to COVID-19 — United States, June 30, 2020

Abbreviation: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

* Comparisons within subgroups were evaluated using Poisson regressions used to calculate

a prevalence ratio adjusted for all characteristics shown in figure.

† 95% confidence intervals indicated with error bars.

§

“Other” race includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific

Islander, or Other.

¶ Selected underlying medical conditions known to increase the risk for severe COVID-19

were obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and any type

of cancer. Obesity is defined as body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 and was calculated from

self-reported height and weight (https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html).

The remaining conditions were assessed using the question “Have you ever been diagnosed

with any of the following conditions?” with response options of 1) “Never”; 2) “Yes,

I have in the past, but don’t have it now”; 3) “Yes I have, but I do not regularly

take medications or receive treatment”; and 4) “Yes I have, and I am regularly taking

medications or receiving treatment.” Respondents who answered that they have been

diagnosed and chose either response 3 or 4 were considered as having the specified

medical condition.

** Essential worker status was self-reported. For the adjusted prevalence ratios,

essential workers were compared with all other respondents (including those who were

nonessential workers, retired, unemployed, and students).

†† Unpaid caregiver status was self-reported. Unpaid caregivers for adults were defined

as having provided unpaid care to a relative or friend aged ≥18 years to help them

take care of themselves at any time in the last 3 months.

The figure is a forest plot showing the adjusted prevalence ratios for characteristics

associated with delay or avoidance of urgent or emergency medical care because of

concerns related to COVID-19, in the United States, as of June 30, 2020.

TABLE 2

Characteristics associated with delay or avoidance of any medical care because of

concerns related to COVID-19 — United States, June 30, 2020

Characteristic

Weighted* no.

Avoided or delayed any medical care

aPR†

(95% CI†)

P-value†

All respondents

4,975

—

—

—

Gender

Female

2,528

Referent

—

—

Male

2,447

0.81

(0.75–0.87)§

<0.001

Age group, yrs

18–24

650

1.12

(1.01–1.25)§

0.035

25–44

1,740

Referent

—

—

45–64

1,727

0.80

(0.72–0.88)§

<0.001

≥65

858

0.72

(0.64–0.81)§

<0.001

Race/Ethnicity

White, non-Hispanic

3,168

Referent

—

—

Black, non-Hispanic

607

1.07

(0.96–1.19)

0.235

Asian, non-Hispanic

238

1.04

(0.91–1.18)

0.567

Other race or multiple races, non-Hispanic¶

150

0.87

(0.71–1.07)

0.196

Hispanic, any race or races

813

1.15

(1.03–1.27)§

0.012

Disability**

Yes

1,108

1.33

(1.23–1.43)§

<0.001

No

3,867

Referent

—

—

Underlying medical condition††

No

2,537

Referent

—

—

One

1,328

1.15

(1.05–1.25)§

0.004

Two or more

1,110

1.31

(1.20–1.42)§

<0.001

Education

Less than high school diploma

65

0.72

(0.53–0.98)§

0.037

High school diploma

833

0.79

(0.71–0.89)§

<0.001

Some college

1,302

0.85

(0.78–0.93)§

0.001

Bachelor's degree

1,755

Referent

—

—

Professional degree

1,020

0.90

(0.82–0.98)§

0.019

Essential workers vs others§§

Essential workers

1,707

1.00

(0.92–1.09)

0.960

Other respondents (nonessential workers, retired persons, unemployed persons, and

students)

3,268

Referent

—

—

Unpaid caregiver status¶¶

Unpaid caregiver for adults

1,344

1.64

(1.52–1.78)§

<0.001

Not unpaid caregiver for adults

3,631

Referent

—

—

U.S. Census region***

Northeast

1,122

Referent

—

—

Midwest

936

0.93

(0.83–1.04)

0.214

South

1,736

0.90

(0.82–0.99)§

0.028

West

1,181

0.99

(0.89–1.09)

0.808

Rural/Urban classification†††

Urban

4,411

1.00

(0.89–1.12)

0.993

Rural

564

Referent

—

—

Health insurance status

Yes

4,577

1.61

(1.31–1.98)§

<0.001

No

398

Referent

—

—

Know someone with positive test results for SARS-CoV-2§§§

Yes

989

1.22

(1.12–1.33)§

<0.001

No

3,986

Referent

—

—

Knew someone who died from COVID-19

Yes

364

0.99

(0.88–1.12)

0.860

No

4,611

Referent

—

—

Believed to be in a group at high risk for severe COVID-19

Yes

981

1.33

(1.23–1.44)§

<0.001

No

3,994

Referent

—

—

Abbreviations: aPR = adjusted prevalence ratio; CI = confidence interval; COVID-19 = coronavirus

disease 2019.

* Statistical raking and weight trimming were employed to improve the cross-sectional

June cohort representativeness of the U.S. population by gender, age, and race/ethnicity

according to the 2010 U.S. Census.

† Comparisons within subgroups were evaluated using Poisson regressions used to calculate

a prevalence ratio adjusted for all characteristics listed, as well as a 95% CI and

p-value. Statistical significance was evaluated at a threshold of α = 0.05.

§ P-value calculated using Poisson regression among respondents within a characteristic

is statistically significant at levels of p<0.05.

¶ “Other” race includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific

Islander, or Other.

** Persons who had a disability were defined based on a qualifying response to either

one of two questions: “Are you limited in any way in any activities because of physical,

mental, or emotional condition?” and “Do you have any health conditions that require

you to use special equipment, such as a cane, wheelchair, special bed, or special

telephone?” https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdf-ques/2015-brfss-questionnaire-12-29-14.pdf.

†† Selected underlying medical conditions known to increase the risk for severe COVID-19

were obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and any type

of cancer. Obesity is defined as body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 and was calculated from

self-reported height and weight (https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html).

The remaining conditions were assessed using the question “Have you ever been diagnosed

with any of the following conditions?” with response options of 1) “Never”; 2) “Yes,

I have in the past, but don’t have it now”; 3) “Yes I have, but I do not regularly

take medications or receive treatment”; and 4) “Yes I have, and I am regularly taking

medications or receiving treatment.” Respondents who answered that they have been

diagnosed and chose either response 3 or 4 were considered as having the specified

medical condition.

§§ Essential worker status was self-reported. For the adjusted prevalence ratios,

essential workers were compared with all other respondents (including those who were

nonessential workers, retired, unemployed, and students).

¶¶ Unpaid caregiver status was self-reported. Unpaid caregivers for adults were defined

as having provided unpaid care to a relative or friend aged ≥18 years at any time

in the last 3 months. Examples provided to survey respondents included helping with

personal needs, household chores, health care tasks, managing a person’s finances,

taking them to a doctor’s appointment, arranging for outside services, and visiting

regularly to see how they are doing.

*** Region classification was determined by using the U.S. Census Bureau’s Census

Regions and Divisions. https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf.

††† Rural/urban classification was determined by using self-reported ZIP codes according

to the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy definition of rurality. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/definition/datafiles.html.

§§§ For this question, respondents were asked to select the following statement, if

applicable: “I know someone who has tested positive for COVID-19.”

Discussion

As of June 30, 2020, an estimated 41% of U.S. adults reported having delayed or avoided

medical care during the pandemic because of concerns about COVID-19, including 12%

who reported having avoided urgent or emergency care. These findings align with recent

reports that hospital admissions, overall emergency department (ED) visits, and the

number of ED visits for heart attack, stroke, and hyperglycemic crisis have declined

since the start of the pandemic (

3

–

5

), and that excess deaths directly or indirectly related to COVID-19 have increased

in 2020 versus prior years (

2

). Nearly one third of adult respondents reported having delayed or avoided routine

medical care, which might reflect adherence to community mitigation efforts such as

stay-at-home orders, temporary closures of health facilities, or additional factors.

However, if routine care avoidance were to be sustained, adults could miss opportunities

for management of chronic conditions, receipt of routine vaccinations, or early detection

of new conditions, which might worsen outcomes.

Avoidance of both urgent or emergency and routine medical care because of COVID-19

concerns was highly prevalent among unpaid caregivers for adults, respondents with

two or more underlying medical conditions, and persons with disabilities. For caregivers

who reported caring for adults at increased risk for severe COVID-19, concern about

exposure of care recipients might contribute to care avoidance. Persons with underlying

medical conditions that increase their risk for severe COVID-19 (

6

) are more likely to require care to monitor and treat these conditions, potentially

contributing to their more frequent report of avoidance. Moreover, persons at increased

risk for severe COVID-19 might have avoided health care facilities because of perceived

or actual increased risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2, particularly at the onset of the

pandemic. However, health care facilities are implementing important safety precautions

to reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection among patients and personnel. In contrast,

delay or avoidance of care might increase risk for life-threatening medical emergencies.

In a recent study, states with large numbers of COVID-19–associated deaths also experienced

large proportional increases in deaths from other underlying causes, including diabetes

and cardiovascular disease (

7

). For persons with disabilities, accessing medical services might be challenging

because of disruptions in essential support services, which can result in adverse

health outcomes. Medical services for persons with disabilities might also be disrupted

because of reduced availability of accessible transportation, reduced communication

in accessible formats, perceptions of SARS-CoV-2 exposure risk, and specialized needs

that are difficult to address with routine telehealth delivery during the pandemic

response. Increasing accessibility of medical and telehealth services

¶¶¶

might help prevent delay of needed care.

Increased prevalences of reported urgent or emergency care avoidance among Black adults

and Hispanic adults compared with White adults are especially concerning given increased

COVID-19-associated mortality among Black adults and Hispanic adults (

8

). In the United States, the age-adjusted COVID-19 hospitalization rates are approximately

five times higher among Black persons and four times higher among Hispanic persons

than are those among White persons (

9

). Factors contributing to racial and ethnic disparities in SARS-CoV-2 exposure, illness,

and mortality might include long-standing structural inequities that influence life

expectancy, including prevalence and underlying medical conditions, health insurance

status, and health care access and utilization, as well as work and living circumstances,

including use of public transportation and essential worker status. Communities, health

care systems, and public health agencies can foster equity by working together to

ensure access to information, testing, and care to assure maintenance and management

of physical and mental health.

The higher prevalence of medical care delay or avoidance among respondents with health

insurance versus those without insurance might reflect differences in medical care-seeking

behaviors. Before the pandemic, persons without insurance sought medical care much

less frequently than did those with insurance (

10

), resulting in fewer opportunities for medical care delay or avoidance.

The findings in this report are subject to at least five limitations. First, self-reported

data are subject to recall, response, and social desirability biases. Second, the

survey did not assess reasons for COVID-19–associated care avoidance, such as adherence

to public health recommendations; closure of health care provider facilities; reduced

availability of public transportation; fear of exposure to infection with SARS-CoV-2;

or availability, accessibility, and acceptance or recognition of telemedicine as a

means of providing care in lieu of in-person services. Third, the survey did not assess

baseline patterns of care-seeking or timing or duration of care avoidance. Fourth,

perceptions of whether a condition was life-threatening might vary among respondents.

Finally, although quota sampling methods and survey weighting were employed to improve

cohort representativeness, this web-based survey might not be fully representative

of the U.S. population for income, educational attainment, and access to technology.

However, the findings are consistent with reported declines in hospital admissions

and ED visits during the pandemic (

3

–

5

).

CDC has issued guidance to assist persons at increased risk for severe COVID-19 in

staying healthy and safely following treatment plans**** and to prepare health care

facilities to safely deliver care during the pandemic.

††††

Additional public outreach in accessible formats tailored for diverse audiences might

encourage these persons to seek necessary care. Messages could highlight the risks

of delaying needed care, especially among persons with underlying medical conditions,

and the importance of timely emergency care. Patient concerns related to potential

exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in health care settings could be addressed by describing facilities’

precautions to reduce exposure risk.

Further exploration of underlying reasons for medical care avoidance is needed, including

among persons with disabilities, persons with underlying health conditions, unpaid

caregivers for adults, and those who face structural inequities. If care were avoided

because of concern about SARS-CoV-2 exposure or if there were closures or limited

options for in-person services, providing accessible telehealth or in-home health

care could address some care needs. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, persons experiencing

a medical emergency should seek and be provided care without delay (

3

).

Summary

What is already known about this topic?

Delayed or avoided medical care might increase morbidity and mortality associated

with both chronic and acute health conditions.

What is added by this report?

By June 30, 2020, because of concerns about COVID-19, an estimated 41% of U.S. adults

had delayed or avoided medical care including urgent or emergency care (12%) and routine

care (32%). Avoidance of urgent or emergency care was more prevalent among unpaid

caregivers for adults, persons with underlying medical conditions, Black adults, Hispanic

adults, young adults, and persons with disabilities.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Understanding factors associated with medical care avoidance can inform targeted care

delivery approaches and communication efforts encouraging persons to safely seek timely

routine, urgent, and emergency care.

Related collections

Most cited references7

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Coronavirus Disease 2019 Case Surveillance — United States, January 22–May 30, 2020

Erin K. Stokes, Laura Zambrano, Kayla N. Anderson … (2020)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Emergency Department Visits — United States, January 1, 2019–May 30, 2020

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Routine Pediatric Vaccine Ordering and Administration — United States, 2020

Jeanne Santoli, Megan C Lindley, Malini B. DeSilva … (2020)