- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Health Center Testing for SARS-CoV-2 During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, June 5–October 2, 2020

research-article

Lisa Romero , DrPH

1

,

,

Leah Zilversmit Pao , PhD

1 ,

Hollie Clark , MPH

1 ,

Catharine Riley , PhD

1 ,

Sharifa Merali , MPH

1 ,

Michael Park , PhD

1 ,

Carrie Eggers , MPH

1 ,

Stephanie Campbell , MPH

2 ,

Cuong Bui

2 ,

Joshua Bolton , MS

2 ,

Xuan Le , AM

2 ,

Robyn Neblett Fanfair , MD

1 ,

Michelle Rose , PhD

1 ,

Alison Hinckley , PhD

1 ,

Charlene Siza , DVM

1

18 December 2020

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

Long-standing social inequities and health disparities have resulted in increased

risk for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection, severe illness, and death

among racial and ethnic minority populations. The Health Resources and Services Administration

(HRSA) Health Center Program supports nearly 1,400 health centers that provide comprehensive

primary health care* to approximately 30 million patients in 13,000 service sites

across the United States.

†

In 2019, 63% of HRSA health center patients who reported race and ethnicity identified

as members of racial ethnic minority populations (

1

). Historically underserved communities and populations served by health centers have

a need for access to important information and resources for preventing exposure to

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, to testing for those at risk, and to follow-up

services for those with positive test results.

§

During the COVID-19 public health emergency, health centers

¶

have provided and continue to provide testing and follow-up care to medically underserved

populations**; these centers are capable of reaching areas disproportionately affected

by the pandemic.

††

HRSA administers a weekly, voluntary Health Center COVID-19 Survey

§§

to track health center COVID-19 testing capacity and the impact of COVID-19 on operations,

patients, and personnel. Potential respondents can include up to 1,382 HRSA-funded

health centers.

¶¶

To assess health centers’ capacity to reach racial and ethnic minority groups at increased

risk for COVID-19 and to provide access to testing, CDC and HRSA analyzed survey data

for the weeks June 5–October 2, 2020*** to describe all patients tested (3,194,838)

and those who received positive SARS-CoV-2 test results (308,780) by race/ethnicity

and state of residence. Among persons with known race/ethnicity who received testing

(2,506,935), 36% were Hispanic/Latino (Hispanic), 38% were non-Hispanic White (White),

and 20% were non-Hispanic Black (Black); among those with known race/ethnicity with

positive test results, 56% were Hispanic, 24% were White, and 15% were Black. Improving

health centers’ ability to reach groups at increased risk for COVID-19 might reduce

transmission by identifying cases and supporting contact tracing and isolation. Efforts

to improve coordination of COVID-19 response-related activities between state and

local public health departments and HRSA-funded health centers can increase access

to testing and follow-up care for populations at increased risk for COVID-19.

HRSA administers a weekly voluntary Health Center COVID-19 Survey to track health

center COVID-19 testing capacity and the impact of COVID-19 on operations, patients,

and staff members. The 1,382 health centers asked to complete the survey are located

in all 50 states, the District of Columbia (DC), and five territories and freely associated

states.

†††

This analysis used survey data from the weeks ending June 5–October 2, 2020, to describe

the patient population and, among all patients who received testing for SARS-CoV-2

with viral tests (i.e., polymerase chain reaction and antigen tests), the numbers

and proportions of persons with tests and positive results by race/ethnicity and state

of residence. State survey response rates ranged from 68% to 80% among health centers.

Proportions of patients receiving SARS-CoV-2 tests and positive test results included

unreported race/ethnicity as a separate category.

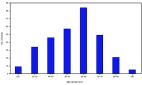

As reported in the HRSA Uniform Data System in 2019, HRSA-funded health centers reported

that 35% of their national patient population was White, 35% Hispanic,

§§§

18% Black, 4% Asian, 1% American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN), 1% Native Hawaiian/Other

Pacific Islander, and 1.3% multiracial persons; race/ethnicity was not reported for

6% of the patient population (Figure) (

1

). By comparison, the 2019 American Community Survey

¶¶¶

estimated that the U.S. population comprises 60% White, 18% Hispanic, 12% Black, 6%

Asian, 1% AI/AN, 0.2% Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and 3% multiracial persons.

FIGURE

Racial/ethnic distribution of 2019 national* and Health Resources and Services Administration

(HRSA)–funded health center

†

patient populations

§

and persons who received testing and had positive SARS-CoV-2 test results

¶

— Health Center COVID-19 Survey, United States, June 5–October 2, 2020

Abbreviations: AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease

2019; HC = health center; NH/PI = Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander; NH = non-Hispanic.

* Data from the 2019 American Community Survey (https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?d=ACS%201-Year%20Estimates%20Data%20Profiles&tid=ACSDP1Y2019.

DP05&hidePreview=false). Data include non-Hispanic NH/PI (0.2%), not visible in figure

and do not include other race (0.3%). Persons with multiracial or unreported race/ethnicity

have an unreported or non-Hispanic ethnicity.

† HRSA–funded health centers include both Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs)

and Health Center Program Look-Alikes (i.e, meets all Health Care Center Program requirements

but does not receive federal funding). During the COVID-19 pandemic, HRSA provided

one-time COVID-19 funding to FQHCs and Health Center Look-Alikes to purchase, administer,

and expand capacity for testing to monitor and suppress COVID-19 testing and response-related

activities.

§ HRSA 2019 Uniform Data System. https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/data-reporting/program-data/national.

¶ HRSA COVID-19 Survey, June 5–October 2, 2020. Data for the number tested or the

number tested positive are aggregated by health centers before submission and cannot

be deduplicated, which might inflate or misrepresent the number of patients tested

or who had positive test results.

The figure is a bar graph showing the racial/ethnic distribution of U.S. 2019 national

and Health Resources and Services Administration–funded health center patient populations

and persons who received testing and had positive SARS-CoV-2 test results during June

5–October 2, 2020, based on data from the Health Center COVID-19 Survey.

During June 5–October 2, 2020, health centers responding to the survey reported that

3,194,838 patients received testing and 308,780 had positive SARS-CoV-2 test results.

Compared to other jurisdictions, Texas reported the highest number of patients who

received testing (353,081; 11%), and California reported the highest number of patients

who had positive test results (46,113; 15%). Based on data reported to the Health

Center COVID-19 Survey, White and Hispanic patients each accounted for 29% of patients

who received testing for SARS-CoV-2 (Table 1) and, among patients who received positive

test results, 19% were White and 45% were Hispanic (Table 2). Overall, race was not

reported for 22% (687,903) of patients tested and 19% of patients with positive test

results (57,208); 1% (26,386) of patients receiving testing and 1% (2,378) of patients

with positive test results were multiracial. In Puerto Rico, 96% of patients receiving

testing were Hispanic; among other jurisdictions, the highest proportions of patients

receiving testing who were Hispanic were in Nevada (9,990; 56%) and New Mexico (11,705;

56%). Compared with all other jurisdictions, California reported the most Hispanic

patients who received testing (186,034) and the most positive test results among Hispanic

patients (33,310; 18%). Among those with positive test results, Puerto Rico reported

the largest proportion of Hispanic patients (2,095; 98%) and New Mexico the second

highest proportion (531; 73%). Nationally, Black patients accounted for 15% of patients

receiving testing and 12% of those who received positive test results. Mississippi

reported the highest proportion of patients who received testing who were Black (25,850;

67%) and the highest proportion of those who had positive test results who were Black

(2,348; 69%). Georgia reported the largest number of tests conducted (42,889; 43%)

and positive test results (4,204; 32%) among Black patients.

TABLE 1

Viral testing for SARS-CoV-2,* by race/ethnicity and jurisdiction

†

— Health Center COVID-19 Survey, United States, June 5–October 2, 2020

Jurisdiction

No.§ of FQHCs¶

Response range** (%)

Total no. patients tested††

Race/Ethnicity, no. tested (row %)

Hispanic/Latino

White, NH

Black, NH

Asian, NH

AI/AN, NH

NH/PI, NH

Multiracial

Unreported

United States

1,382–1,376

68–80

3,194,838

913,718 (29)

941,017 (29)

491,311 (15)

77,528 (2)

36,837 (1)

5,161 (—)

26,386 (1)

687,903 (22)

Alabama

17

59–94

46,146

3,393 (7)

16,089 (35)

21,262 (46)

183 (—)

139 (—)

4 (—)

241 (1)

4,800 (10)

Alaska

27

44–74

57,147

1,788 (3)

11,510 (20)

528 (1)

967 (2)

20,785 (36)

83 (—)

362 (1)

21,080 (37)

American Samoa

1

0–100

1,567

104 (7)

46 (3)

0 (—)

55 (4)

12 (1)

0 (—)

2 (—)

8 (1)

Arizona

23

65–83

53,455

27,220 (51)

15,584 (29)

1,509 (3)

335 (1)

1,741 (3)

50 (—)

392 (1)

6,573 (12)

Arkansas

12

50–100

51,488

7,855 (15)

24,988 (49)

13,061 (25)

243 (—)

152 (—)

21 (—)

189 (—)

4,169 (8)

California

175–178

59–74

336,454

186,034 (55)

51,114 (15)

26,371 (8)

20,103 (6)

949 (—)

634 (—)

4,891 (1)

45,217 (13)

Colorado

19

68–95

59,401

24,702 (42)

19,064 (32)

5,165 (9)

1,166 (2)

324 (1)

31 (—)

791 (1)

8,123 (14)

Connecticut

16

56–94

83,507

27,872 (33)

15,803 (19)

8,258 (10)

1,190 (1)

218 (—)

20 (—)

349 (—)

29,613 (35)

Delaware

3

33–100

2,356

894 (38)

466 (20)

850 (36)

31 (1)

9 (—)

4 (—)

14 (1)

88 (4)

District of Columbia

8

63–100

18,438

5,632 (31)

1,628 (9)

8,554 (46)

274 (1)

30 (—)

2 (—)

89 (—)

2,215 (12)

Federated States of Micronesia

4

25–100

198

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

54 (27)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

Florida

47

62–87

257,119

97,542 (38)

51,704 (20)

38,483 (15)

1,868 (1)

189 (—)

44 (—)

2,431 (1)

64,665 (25)

Georgia

35

60–91

100,909

15,410 (15)

32,664 (32)

42,889 (43)

1,119 (1)

67 (—)

11 (—)

862 (1)

7,861 (8)

Guam

1

0–100

8,574

31 (—)

199 (2)

38 (—)

2,572 (30)

9 (—)

4 (—)

432 (5)

268 (3)

Hawaii

14

36–86

8,894

850 (10)

911 (10)

91 (1)

1,325 (15)

13 (—)

2,833 (32)

286 (3)

1,081 (12)

Idaho

14

71–100

12,111

3,014 (25)

6,281 (52)

168 (1)

100 (1)

1,028 (8)

25 (—)

26 (—)

1,460 (12)

Illinois

45

64–82

162,663

51,534 (32)

37,781 (23)

22,276 (14)

3,097 (2)

217 (—)

44 (—)

676 (—)

46,966 (29)

Indiana

27

48–78

20,639

6,031 (29)

5,570 (27)

2,035 (10)

967 (5)

34 (—)

3 (—)

112 (1)

5,876 (28)

Iowa

14

64–93

30,891

5,292 (17)

14,786 (48)

1,511 (5)

447 (1)

222 (1)

16 (—)

235 (1)

8,357 (27)

Kansas

19

53–100

25,472

6,582 (26)

13,631 (54)

1,972 (8)

326 (1)

336 (1)

93 (—)

212 (1)

2,264 (9)

Kentucky

25

76–96

64,494

3,453 (5)

51,839 (80)

4,141 (6)

446 (1)

36 (—)

15 (—)

506 (1)

4,017 (6)

Louisiana

36

61–81

48,007

5,297 (11)

16,396 (34)

21,333 (44)

487 (1)

143 (—)

39 (—)

323 (1)

3,968 (8)

Maine

18

50–89

9,049

600 (7)

6,614 (73)

515 (6)

40 (—)

40 (—)

7 (—)

43 (—)

1,189 (13)

Marshall Islands

1

0–100

121

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

1 (1)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

Maryland

17

47–82

8,898

2,696 (30)

1,824 (20)

2,629 (30)

117 (1)

248 (3)

3 (—)

135 (2)

1,242 (14)

Massachusetts

37–38

59–89

153,411

51,639 (34)

52,813 (34)

16,444 (11)

5,326 (3)

181 (—)

61 (—)

817 (1)

25,712 (17)

Michigan

39

51–79

99,960

12,870 (13)

53,804 (54)

13,622 (14)

1,799 (2)

305 (—)

46 (—)

1,040 (1)

16,412 (16)

Minnesota

16

56–81

16,645

2,828 (17)

5,093 (31)

3,627 (22)

1,178 (7)

794 (5)

5 (—)

32 (—)

3,077 (18)

Mississippi

20

65–95

38,843

3,411 (9)

8,300 (21)

25,850 (67)

218 (1)

59 (—)

9 (—)

326 (1)

605 (2)

Missouri

28–29

66–90

78,075

7,414 (9)

36,275 (46)

16,802 (22)

677 (1)

207 (—)

57 (—)

567 (1)

15,895 (20)

Montana

14

43–86

18,377

368 (2)

7,522 (41)

31 (—)

18 (—)

441 (2)

7 (—)

60 (—)

9,928 (54)

Nebraska

7

57–86

9,224

3,585 (39)

2,167 (23)

2,008 (22)

896 (10)

40 (—)

6 (—)

97 (1)

422 (5)

Nevada

8

38–88

17,827

9,990 (56)

4,102 (23)

938 (5)

1,145 (6)

47 (—)

157 (1)

94 (1)

1,322 (7)

New Hampshire

10

70–100

3,535

936 (26)

2,140 (61)

88 (2)

80 (2)

6 (—)

3 (—)

10 (—)

272 (8)

New Jersey

23–24

33–67

51,393

26,433 (51)

9,698 (19)

7,173 (14)

603 (1)

62 (—)

43 (—)

398 (1)

6,887 (13)

New Mexico

16

75–100

20,857

11,705 (56)

4,115 (20)

295 (1)

98 (—)

1,427 (7)

12 (—)

208 (1)

2,985 (14)

New York

63

48–67

204,075

31,877 (16)

32,798 (16)

24,734 (12)

5,972 (3)

194 (—)

30 (—)

1,606 (1)

106,749 (52)

North Carolina

39

46–69

65,685

14,505 (22)

18,118 (28)

22,130 (34)

661 (1)

524 (1)

66 (—)

334 (1)

9,326 (14)

North Dakota

4

75–100

5,003

199 (4)

2,425 (48)

385 (8)

170 (3)

300 (6)

9 (—)

35 (1)

1,476 (30)

Northern Mariana Islands

1

0–100

0

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

Ohio

51

67–82

72,400

7,604 (11)

37,561 (52)

13,461 (19)

1,216 (2)

443 (1)

39 (—)

550 (1)

11,418 (16)

Oklahoma

21

52–95

13,147

2,833 (22)

5,284 (40)

1,151 (9)

86 (1)

480 (4)

16 (—)

145 (1)

3,117 (24)

Oregon

30

73–90

17,782

6,771 (38)

7,471 (42)

474 (3)

400 (2)

686 (4)

40 (—)

145 (1)

1,697 (10)

Palau

1

0–100

1,612

0 (—)

254 (16)

4 (—)

334 (21)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

Pennsylvania

43

67–91

54,143

9,563 (18)

22,464 (41)

13,911 (26)

2,549 (5)

118 (—)

13 (—)

651 (1)

4,745 (9)

Puerto Rico

21–22

73–91

28,909

27,709 (96)

134 (—)

5 (—)

0 (—)

3 (—)

0 (—)

260 (1)

798 (3)

Rhode Island

8

63–100

22,637

10,653 (47)

4,907 (22)

2,120 (9)

388 (2)

55 (—)

9 (—)

241 (1)

4,228 (19)

South Carolina

23

70–91

63,976

4,705 (7)

15,311 (24)

36,609 (57)

686 (1)

124 (—)

12 (—)

321 (1)

6,097 (10)

South Dakota

4

50–100

5,966

1,194 (20)

3,536 (59)

67 (1)

223 (4)

283 (5)

14 (—)

16 (—)

631 (11)

Tennessee

29

59–83

85,712

8,496 (10)

53,673 (63)

8,411 (10)

430 (1)

63 (—)

53 (—)

1,018 (1)

13,549 (16)

Texas

72

69–85

353,081

109,844 (31)

55,515 (16)

42,531 (12)

10,324 (3)

766 (—)

170 (—)

1,510 (—)

132,353 (37)

U.S. Virgin Islands

2

0–50

365

100 (27)

45 (12)

200 (55)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

20 (5)

0 (—)

Utah

13

62–92

13,870

5,451 (39)

4,663 (34)

209 (2)

65 (—)

622 (4)

26 (—)

125 (1)

2,671 (19)

Vermont

11

64–100

5,017

143 (3)

4,415 (88)

42 (1)

41 (1)

16 (—)

0 (—)

10 (—)

348 (7)

Virginia

26

65–88

35,346

8,234 (23)

15,027 (43)

6,979 (20)

381 (1)

140 (—)

4 (—)

211 (1)

4,350 (12)

Washington

27

70–89

98,481

34,877 (35)

30,972 (31)

3,647 (4)

3,844 (4)

1,317 (1)

240 (—)

1,664 (2)

20,566 (21)

West Virginia

28

61–89

47,084

2,864 (6)

39,019 (83)

1,748 (4)

48 (—)

18 (—)

12 (—)

221 (—)

3,153 (7)

Wisconsin

16

69–100

23,098

10,532 (46)

4,309 (19)

1,962 (8)

153 (1)

150 (1)

15 (—)

33 (—)

5,932 (26)

Wyoming

6

33–83

1,304

559 (43)

595 (46)

14 (1)

6 (—)

25 (2)

1 (—)

22 (2)

82 (6)

Abbreviations: AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease

2019; FQHC = Federally Qualified Health Center; NH/PI = Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific

Islander; NH = non-Hispanic.

* SARS-CoV-2 viral tests include polymerase chain reaction and antigen tests.

† The Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA) funds health centers in all

50 states, the District of Columbia, and the following U.S. territories and freely

associated states: American Samoa, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Northern

Mariana Islands, Marshall Islands, Puerto Rico, and U.S. Virgin Islands.

§ In June 2020, the number of HRSA-fund health centers was 1,382. By September, the

number of HRSA-funded centers decreased to 1,376, by three in California and by one

each in Massachusetts, Missouri, New Jersey, and Puerto Rico. By October, the number

of Puerto Rico’s HRSA-funded health centers increased by one.

¶ FQHCs receive HRSA Health Center Program federal grant funding to improve the health

of underserved populations

** The weekly response rate was calculated using the number of health centers that

responded to the survey as the numerator and number of current HRSA-funded health

centers as the denominator. The response range represents the lowest response rate

and the highest response rate nationally and by state during June 5–October 2, 2020.

†† Data for the number of persons receiving testing or who had positive test results

are aggregated by health center before submission and cannot be deduplicated, which

might inflate or misrepresent the number of patients who received testing or who had

positive test results.

TABLE 2

Positive viral tests for SARS-CoV-2,* by race/ethnicity and jurisdiction

†

— Health Center COVID-19 Survey, United States, June 5–October 2, 2020

Jurisdiction

Total positive§

Race/Ethnicity, no. positive (row %)

Hispanic/Latino

White, NH

Black, NH

Asian, NH

AI/AN, NH

NH/PI, NH

Multiracial

Unreported

United States

308,780

140,462 (45)

59,959 (19)

38,385 (12)

6,792 (2)

1,262 (—)

473 (—)

2,378 (1)

57,208 (19)

Alabama

5,097

710 (14)

1,469 (29)

2,296 (45)

23 (—)

14 (—)

0 (—)

32 (1)

542 (11)

Alaska

961

81 (8)

167 (17)

31 (3)

18 (2)

253 (26)

0 (—)

7 (1)

399 (42)

American Samoa

0

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

Arizona

8,297

4,719 (57)

1,857 (22)

243 (3)

25 (—)

178 (2)

9 (—)

70 (1)

1,190 (14)

Arkansas

5,946

1,808 (30)

1,738 (29)

883 (15)

14 (—)

13 (—)

7 (—)

10 (—)

886 (15)

California

46,113

33,310 (72)

4,075 (9)

2,458 (5)

997 (2)

76 (—)

63 (—)

572 (1)

4,470 (10)

Colorado

4,656

3,234 (69)

721 (15)

142 (3)

49 (1)

14 (—)

3 (—)

10 (—)

480 (10)

Connecticut

3,904

2,032 (52)

221 (6)

229 (6)

33 (1)

2 (—)

1 (—)

3 (—)

1,379 (35)

Delaware

244

144 (59)

19 (8)

71 (29)

4 (2)

2 (1)

0 (—)

0 (—)

4 (2)

District of Columbia

1,697

737 (43)

82 (5)

696 (41)

16 (1)

4 (—)

0 (—)

6 (—)

154 (9)

Federated States of Micronesia

0

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

Florida

43,859

17,913 (41)

3,500 (8)

3,347 (8)

131 (—)

9 (—)

2 (—)

142 (—)

18,802 (43)

Georgia

13,130

2,984 (23)

4,213 (32)

4,204 (32)

69 (1)

6 (—)

2 (—)

48 (—)

1,597 (12)

Guam

633

2 (—)

5 (1)

0 (—)

222 (35)

0 (—)

0 (—)

35 (6)

2 (—)

Hawaii

907

63 (7)

27 (3)

3 (—)

144 (16)

1 (—)

234 (26)

20 (2)

78 (9)

Idaho

2,938

1,185 (40)

991 (34)

119 (4)

55 (2)

94 (3)

18 (1)

9 (—)

467 (16)

Illinois

16,752

6,993 (42)

3,571 (21)

2,074 (12)

151 (1)

16 (—)

1 (—)

55 (—)

3,874 (23)

Indiana

3,274

1,372 (42)

600 (18)

238 (7)

152 (5)

2 (—)

0 (—)

12 (—)

897 (27)

Iowa

3,634

1,011 (28)

1,550 (43)

141 (4)

68 (2)

14 (—)

1 (—)

25 (1)

821 (23)

Kansas

2,810

1,345 (48)

986 (35)

177 (6)

27 (1)

30 (1)

5 (—)

3 (—)

226 (8)

Kentucky

4,191

579 (14)

2,884 (69)

306 (7)

35 (1)

0 (—)

2 (—)

22 (1)

361 (9)

Louisiana

4,922

734 (15)

1,826 (37)

2,088 (42)

29 (1)

11 (—)

0 (—)

37 (1)

191 (4)

Maine

119

28 (24)

42 (35)

43 (36)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

1 (1)

5 (4)

Marshall Islands

0

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

Maryland

1,472

763 (52)

148 (10)

410 (28)

24 (2)

13 (1)

1 (—)

19 (1)

93 (6)

Massachusetts

10,029

6,755 (67)

1,167 (12)

696 (7)

312 (3)

1 (—)

1 (—)

50 (—)

1,031 (10)

Michigan

3,931

1,060 (27)

1,455 (37)

460 (12)

65 (2)

9 (—)

2 (—)

48 (1)

828 (21)

Minnesota

2,194

991 (45)

219 (10)

527 (24)

190 (9)

22 (1)

1 (—)

2 (—)

241 (11)

Mississippi

3,412

255 (7)

686 (20)

2,348 (69)

23 (1)

7 (—)

1 (—)

29 (1)

54 (2)

Missouri

5,770

1,319 (23)

2,310 (40)

1,090 (19)

48 (1)

8 (—)

0 (—)

23 (—)

916 (16)

Montana

865

26 (3)

323 (37)

2 (—)

1 (—)

30 (3)

1 (—)

2 (—)

480 (55)

Nebraska

1,749

1,171 (67)

160 (9)

138 (8)

131 (7)

2 (—)

0 (—)

6 (—)

140 (8)

Nevada

2,893

2,029 (70)

325 (11)

121 (4)

127 (4)

7 (—)

21 (1)

14 (—)

245 (8)

New Hampshire

139

91 (65)

32 (23)

8 (6)

4 (3)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

4 (3)

New Jersey

3,275

1,080 (33)

266 (8)

287 (9)

40 (1)

0 (—)

0 (—)

16 (—)

1,584 (48)

New Mexico

729

531 (73)

89 (12)

8 (1)

2 (—)

23 (3)

0 (—)

7 (1)

66 (9)

New York

10,697

1,404 (13)

1,382 (13)

1,507 (14)

1,775 (17)

6 (—)

3 (—)

75 (1)

4,528 (42)

North Carolina

8,467

3,922 (46)

1,846 (22)

1,623 (19)

63 (1)

53 (1)

8 (—)

40 (—)

908 (11)

North Dakota

402

13 (3)

173 (43)

49 (12)

17 (4)

8 (2)

0 (—)

0 (—)

142 (35)

Northern Mariana Islands

0

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

Ohio

4,794

1,014 (21)

1,881 (39)

1,197 (25)

88 (2)

2 (—)

21 (—)

33 (1)

556 (12)

Oklahoma

1,264

500 (40)

419 (33)

70 (6)

14 (1)

46 (4)

1 (—)

10 (1)

197 (16)

Oregon

1,785

1,011 (57)

266 (15)

79 (4)

346 (19)

14 (1)

1 (—)

3 (—)

62 (3)

Palau

0

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

Pennsylvania

3,573

1,105 (31)

954 (27)

719 (20)

357 (10)

7 (—)

1 (—)

87 (2)

333 (9)

Puerto Rico

2,137

2,095 (98)

5 (—)

5 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

32 (1)

Rhode Island

2,808

1,943 (69)

250 (9)

196 (7)

35 (1)

0 (—)

2 (—)

19 (1)

360 (13)

South Carolina

5,399

1,087 (20)

1,075 (20)

2,602 (48)

18 (—)

18 (—)

1 (—)

16 (—)

568 (11)

South Dakota

857

167 (19)

542 (63)

5 (1)

65 (8)

18 (2)

1 (—)

1 (—)

58 (7)

Tennessee

13,014

2,726 (21)

6,116 (47)

1,544 (12)

114 (1)

22 (—)

6 (—)

432 (3)

2,038 (16)

Texas

22,444

15,079 (67)

2,588 (12)

1,725 (8)

397 (2)

47 (—)

2 (—)

180 (1)

2,419 (11)

U.S. Virgin Islands

2

0 (—)

0 (—)

2 (100)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

Utah

1,597

1,099 (69)

284 (18)

20 (1)

6 (—)

48 (3)

1 (—)

17 (1)

116 (7)

Vermont

35

2 (6)

20 (57)

4 (11)

5 (14)

0 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

4 (11)

Virginia

3,966

1,684 (42)

1,272 (32)

633 (16)

23 (1)

6 (—)

0 (—)

17 (—)

331 (8)

Washington

9,601

6,115 (64)

1,295 (13)

265 (3)

219 (2)

92 (1)

39 (—)

95 (1)

1,289 (13)

West Virginia

1,792

249 (14)

1,363 (76)

78 (4)

2 (—)

0 (—)

0 (—)

8 (—)

92 (5)

Wisconsin

3,381

2,090 (62)

418 (12)

175 (5)

19 (1)

6 (—)

10 (—)

4 (—)

650 (19)

Wyoming

223

102 (46)

86 (39)

3 (1)

0 (—)

8 (4)

0 (—)

6 (3)

18 (8)

Abbreviations: AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease

2019; NH = non-Hispanic; NH/PI = Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander.

* SARS-CoV-2 viral tests include polymerase chain reaction and antigen tests.

† The Health Resources Services Administration funds health centers in all 50 states,

the District of Columbia, and the following U.S. territories and freely associated

states: American Samoa, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands,

Marshall Islands, Puerto Rico, and U.S. Virgin Islands.

§ Data for the number of persons receiving testing or who had positive test results

are aggregated by health center before submission and cannot be deduplicated, which

might inflate or misrepresent the number of patients who received testing or who had

positive test results.

Discussion

Health centers’ efforts to increase testing for SARS-CoV-2 are an important mitigation

strategy to reach racial and ethnic minority groups at increased risk for COVID-19.

Published state and national data indicate that racial and ethnic minority groups

might be more likely to become infected with SARS-CoV-2, experience more severe COVID-19–associated

illness, and have higher risk for death from COVID-19 (

2

–

7

). This study contributes to understanding current health center testing patterns

and areas for improvement. Long-standing social inequalities and health disparities

among racial and ethnic minority groups likely result from a multitude of factors

that lead to increased risk for getting ill and dying of COVID-19, including discrimination,****

limited health care access and utilization, occupation, housing, and educational and

income gaps.

††††

Further, these factors might contribute to other risk factors for severe disease and

death, including limited health care access, underlying medical conditions, and higher

levels of environmental exposure. The factors contributing to disparities likely vary

widely within and among groups, depending on geographic location and other contextual

factors.

Health centers have a long-standing commitment to meeting the primary care needs of

their communities (

8

). HRSA has awarded funding

§§§§

to support health centers to purchase, administer, and expand capacity for COVID-19

testing and response-related activities, which has enabled health centers to maintain

or increase their staffing levels, conduct training, purchase personal protective

equipment, and administer tests. Health center services, including testing, contact

tracing, isolation, providing health care, and aiding recovery from the impact of

unintended negative consequences

¶¶¶¶

of mitigation strategies, have increased the capacity of health centers to reach populations

at increased risk for COVID-19 as well as access to testing and care.*****

A recent analysis of SARS-CoV-2 testing in a multistate network of health centers

during the first weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic reported small racial differences

in testing and positivity rates; however, larger differences were identified by ethnicity,

preferred language, and insurance status, underscoring health centers’ unique position

for serving racial and ethnic minority groups and addressing the ongoing need for

targeted, language-concordant testing strategies (

9

). The results of this analysis indicate that health centers have afforded racial

and ethnic minority populations access to SARS-CoV-2 testing during the COVID-19 pandemic

and that these populations were at increased risk for COVID-19, given the large percentage

of positive test results. White and Hispanic patients each accounted for 29% of tests

performed; however, only 19% of positive test results were among White persons who

received testing, whereas 61% were among racial and ethnic minority groups, with the

largest percentage of positive test results (45%) among Hispanic patients. Twenty-six

states and Puerto Rico reported >40% of positive tests among persons of Hispanic ethnicity

with 1.5% of all Hispanic patients receiving testing at Puerto Rican health centers.

The findings in this report are subject to at least five limitations. First, the data

used in this analysis are based on responses from health centers that voluntarily

reported data to the Health Center COVID-19 Survey and might not be representative

of all health centers in the United States, its territories, and freely associated

states. Second, data represent a date range of information provided by health centers

specified by weekly reporting date. Summary information across report dates is not

comparable because of differences in health center responses for a given report date.

Third, race and ethnicity data were missing for approximately 22% of patients who

received testing and 19% of patients who had positive test results. Fourth, the reported

number of patients tested each week does not fully represent the same patients included

in the reported number with positive test results that week because of a lag between

the date the specimen is collected and the availability of test results. Therefore,

positivity cannot be inferred by dividing the number of patients who received positive

test results by the number receiving testing. Finally, data for the number of persons

with testing or positive results are aggregated by health centers before submission

and cannot be deduplicated, which might inflate or misrepresent the number of patients

receiving testing or positive test results.

Health centers are an integral component of health systems designed to address structural

inequities (

10

). During the COVID-19 public health emergency, health centers have played an important

role in providing access to testing in communities disproportionately affected by

COVID-19. Health centers’ ability to reach populations at higher risk for SARS-CoV-2

infection might reduce COVID-19 transmission by identifying cases and supporting public

health contact tracing and isolation among populations they serve.

Summary

What is already known about this topic?

Long-standing social inequities and health disparities have resulted in increased

risk for COVID-19 infection, severe illness, and death among racial and ethnic minority

populations.

What is added by this report?

Health centers have provided racial and ethnic minority populations access to SARS-CoV-2

testing. Improving health centers’ ability to reach groups at increased risk for COVID-19

might reduce transmission by identifying cases and supporting contact tracing and

isolation.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Efforts to improve coordination of COVID-19 response-related activities between state

and local public health departments and HRSA-funded health centers can increase access

to testing and follow-up care for populations at increased risk for COVID-19.

Related collections

Most cited references8

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Coronavirus Disease 2019 Case Surveillance — United States, January 22–May 30, 2020

Erin K. Stokes, Laura Zambrano, Kayla N. Anderson … (2020)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes of Adult Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19 — Georgia, March 2020

Jeremy Gold, Karen Wong, Christine Szablewski … (2020)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Characteristics Associated with Hospitalization Among Patients with COVID-19 — Metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia, March–April 2020

Marie Killerby, Ruth Link-Gelles, Sarah Haight … (2020)