The Fairtrade lobby ignores the degree to which the poorest rural people depend on wage labour incomes, pretending that ‘smallholder’ producers and members of cooperatives are homogeneous and that all or most of them can exit poverty as a result of interventions designed to increase farmers’ income from crop production. The argument here, based on a four-year study of the wages and working conditions of labourers hired by ‘smallholder’ tea and coffee producers in Uganda and Ethiopia, is that activists concerned to reduce poverty should be channelling resources to reward good employers rather than mythical ‘small’ farmers.

Introduction

The arguments in this paper rely on an unusually large amount of labour market data collected by the Fair Trade Employment and Rural Poverty (FTERP) research project and now available on the Web (http://fterp.org). Apart from quantitative surveys covering 1700 respondents, an experienced team also undertook qualitative research over a period of four years between 2010 and 2014. The qualitative research included several hundred informal interviews in Ethiopia and Uganda with cooperative members, cooperative leaders, wage workers, agribusiness executives, civil servants, and donor and non-governmental organisation (NGO) officials. The hope is that the arguments and new data introduced here will allow those analysing poverty reduction prospects in Africa to become far more critical of the partial information provided by the Fairtrade Foundation, Fairtrade International and other Fairtrade organisations, in particular with respect to the implications of Fair Trade for the poorest rural people.

Branding and fairness

A large number of students, trade unionists, pensioners and others on low incomes in the UK pay more – usually a lot more – to buy coffee and tea that is labelled Fairtrade.1 They believe that poor rural people will benefit from these purchases of certified beverages. This belief is based on sophisticated branding and publicity campaigns, partly funded by UKAID and the supermarkets, rather than on independent and careful research.2

Fairtrade is a multi-billion-pound business, with sales of certified products approaching 5 billion euros in 2012. Its branding and advertising have been contracted out to a company whose other clients include Nike and Coca-Cola (http://creativity-online.com/credits/wieden--kennedy-london/87/2). The executives who work for the Fairtrade Foundation and for Cafédirect in the UK earn about 500 times the annual amount earned by the African agricultural wage workers who directly produce the commodities they promote and label. An ‘impartial spectator’ would probably describe this differential as excessive, unjust or even unfair. Salaries greater than 12 times the earnings of low-paid workers were recently defined as unfair by more than one-third of the Swiss electorate (Maclucas 2013), while an even larger proportion of people are angry at the pay gap between executives and ordinary workers in the UK (High Pay Centre 2014). But extreme inequalities in wages, or the returns to labour, are never mentioned in the discussions about the coffee and tea produced by Fairtrade-certified small-producer organisations or cooperatives. The branding exercise prefers to focus on the unequal share of the final consumer price captured by traders, roasters and retailers.

If a local bureaucrat employed by a Fairtrade-certified cooperative in Uganda earns 70 times the wage earned by a woman hired to pluck tea on the farms of the cooperative's members, the Fairtrade lobby does not protest that this gap in earnings is ‘unfair’. Rather, the nationalist rhetoric of unfairness is reserved exclusively for comparisons between the farm gate price of tea/coffee received by African producers and the price in foreign (European and American) supermarkets or coffee bars. Most people are well aware that the price per kilogram in these foreign supermarkets is about 10 times the price received by African farmers and have been persuaded that it is politically correct to proclaim that this discrepancy is ‘unfair’ (Barratt Brown 2007, 271). Few people know or protest about the gulf between the wages received by hired labourers and the incomes received by the African coffee and tea farmers who are their employers.

Spotlighting smallholders and putting wage workers in the shade

In Uganda and Ethiopia (and elsewhere in Africa) the ‘small’ producers of agricultural commodities, whose interests are so vigorously promoted by the Fairtrade lobby, are certainly not a homogeneous group. It does not require many days of rural fieldwork to realise that commodity producers are a mixed bunch; they are differentiated, displaying a wide range of diverse characteristics. All of the simplified, standard definitions and classifications of African farmers used by NGOs and the aid bureaucracy are unhelpful. The almost universally applied dualistic categorisation of ‘smallholder’ (as opposed to ‘estate’ or ‘plantation’ producer) simply ignores differentiation that some ‘smallholders’ operate holdings that are at least 20 times larger than the holdings operated by the average or model smallholder. Some small farmers supported by Fairtrade even enjoy standards of living that many UK pensioners would envy.

As an extreme example, the Fairtrade-certified ‘smallholder’ tea producers who own the Mpanga Growers Tea Factory in Uganda include an individual living in Kampala, farming about 130 hectares of tea and employing dozens of wage workers. Other ‘smallholder’ cooperative members or shareholders of Mpanga have also had to construct permanent labour camps to house the large number of seasonal migrant wage workers they employ to pick their tea. Most of the Board members of this cooperative organisation own well over 10 hectares of tea (as well as other businesses) and employ large numbers of wage workers. It would be misleading to claim that they are the stereotypical smallholders who produce tea by using only their own labour and the labour provided by the members of their family.

The career backgrounds of the largest suppliers of tea to this factory (and the backgrounds of former Board members) include salaried positions as very senior government civil servants and consultants; others have occupied extremely influential local and national political roles. A former Chairman of the Board at Mpanga now owns his own tea factory, an agricultural estate extending to over 9 square kilometres, as well as many commercial urban properties, while remaining a ‘small farm’ shareholder in the Mpanga Growers Factory (Mafaranga 2013).

The Chairman of the Ankole Coffee Producers Cooperative Union (ACPCU) – a Fairtrade-certified Ugandan coffee cooperative studied by the FTEPR – also farms more coffee than most of the other members of the cooperative and spends a great deal of his time in Kampala: so much time that thieves have taken advantage of his absence to steal his coffee cherries. A recently deceased member of one of the ACPCU's primary societies had a farm of 25 hectares planted with coffee. He sold to a (Fairtrade-certified) primary cooperative society until he acquired his own coffee-processing factory. In 2012 he needed to employ about 40 wage workers to pick his coffee. The ACPU coffee cooperative has, for more than a decade, been affiliated with Cafédirect – an organisation that publishes a claim to trade ‘only with smallholders’ or, as stated in their Annual Review, ‘small and disadvantaged growers’. Mpanga Growers Tea Factory has also been supplying Cafédirect for more than a decade.

Similarly, while many smallholder farmers who are members of the Fairtrade-certified Fero Coffee Cooperative in Ethiopia (a primary cooperative member of the Sidama Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union) do only cultivate about one-third of a hectare, some cooperative members (at least 10 of them) cultivate more than 20 times that area. And some of these members with large coffee farms employ about 60 wage workers. Not only do these smallholders cultivate a relatively large area of coffee but, more importantly, their methods of farming and their accumulation strategies are also different in crucial respects. They are capitalist farmers. A realistic analysis of the social relations of production on large ‘smallholder’ coffee and tea farms should be the starting point in any discussion of the impact of donor and NGO interventions to support rural cooperatives and export crop production.

Sales of coffee and tea: the dominant role of a few sellers

Of course, all the published statistics show that the larger-scale smallholders constitute a minority of the total number of coffee or tea producers in cooperatives. However, it is far more important and also far more difficult to unearth statistics that show the contribution of these atypical smallholders to total output, e.g. the proportion of output that is marketed by the top 10% (in terms of volume marketed) of all smallholders selling coffee or tea. In all of our fieldwork sites where there were Fairtrade-certified smallholder organisations, the proportion of output marketed by the hundreds of farmers cultivating average-size holdings, i.e. holdings that are smaller than about 1 hectare, was tiny. FTEPR was able to collect some data from produce ledgers on the volume of coffee marketed in 2011 by the members of two Fairtrade-certified primary coffee cooperatives in Uganda and Ethiopia. The data from these two primary societies, as well as the data on tea from Mpanga, reveal a remarkably similar pattern and are summarised in Figures 1–3.

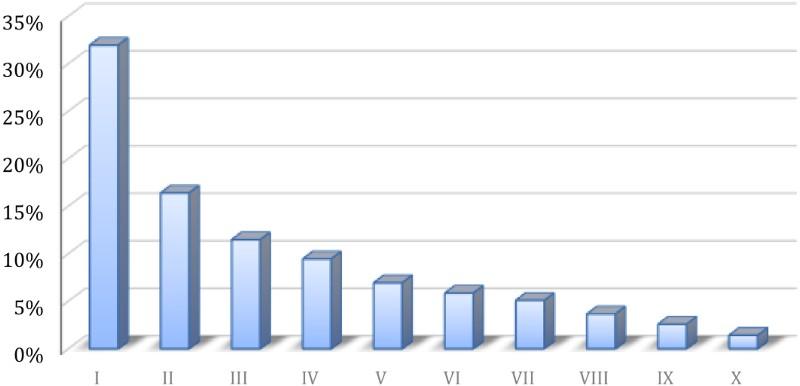

Distribution of the volume of coffee sales in a Ugandan Fairtrade-certified cooperative in 2011, by decile.

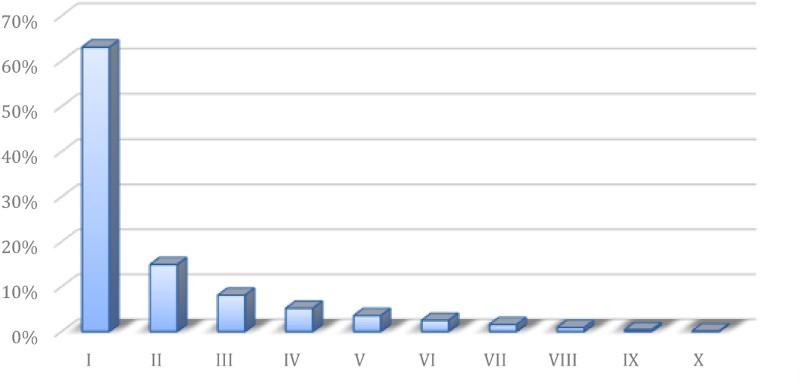

Distribution of the volume of coffee sales in an Ethiopian Fairtrade-certified cooperative in 2011, by decile.

Distribution of the volume of green leaf sales to a Fairtrade-certified smallholder-owned Ugandan tea factory in 2011, by decile.

Out of the 540 recorded members of the Ugandan Primary Society, 143 sold no coffee at all to the Cooperative, while 54 members accounted for nearly half of all sales and the biggest-selling 162 members accounted for more than three-quarters of all sales of coffee to the cooperative.3 Qualitative research in the area covered by this cooperative suggests that some of the cooperative members – those who farm the largest areas of coffee and market a much larger volume of coffee than other members – also sell a relatively large amount of coffee to private traders. Some of the coffee they sell to private traders is a reflection of the fact that they have larger farms and higher yields than most coffee farmers, but part of the reason for the high volume of their sales to the cooperative (and to private buyers) is that they act as traders/transporters/intermediaries, selling coffee produced by others. So the degree of concentration of coffee sales shown in Figure 1 is only one aspect of the degree to which a small group of capitalist farmers dominate local production and marketing; their domination of sales of coffee to private buyers, who claim to purchase about 85% of the coffee produced in the Ugandan Coffee Fairtrade-certified site, is not centrally recorded or published. Of course, Board members of the cooperative deny that they themselves engage in side sales to private traders, although these traders confirmed the prevalence of these sales to FTEPR researchers. Indeed, it is common for cooperative management to bemoan that ordinary members sell to private traders.

In 2011, Fero Primary Cooperative Society in Ethiopia recorded all coffee purchases of more than 20 kilograms from 676 of its members. The amount of coffee sold by these members ranged from a negligible 20 kilograms to an impressive 30,000 kilograms. The member who sold the largest amount of coffee in 2011 used to be the secretary of this Primary Cooperative Society and his older brother was the Society's treasurer. This farmer has for many years been the recipient of substantial direct support from a USAID-funded NGO and admits to employing about 40 men on a regular basis to mulch, weed, hoe and prune his coffee. When researchers asked him about the area of coffee he has planted and how he acquired the land, his answers became increasingly vague and evasive, but local experts believe he is currently farming at least 7 hectares of coffee. There are about a dozen other members of the cooperative, mainly Cooperative Board members or former Board members, who have also received substantial support through USAID, including large interest-free loans, and who are employing relatively large numbers of wage workers to produce both coffee and coffee seedlings. This group aims to sell directly to speciality buyers abroad and wants to stop selling through Fero Primary Cooperative Society, where their revenues must be shared both with a Union bureaucracy they believe is corrupt and with a number of much smaller farmers.4 Figure 2 illustrates the degree to which coffee sales to Fero Primary Cooperative Society in 2011 were dominated by a relatively small number of the Society's members.

Interviews with key informants, as well as the secondary literature on cooperatives in Uganda, Ethiopia and other poor rural areas, confirm that a small group of relatively large (male) producers, such as the top 10% of coffee sellers in Figures 1 and 2, usually control the leadership positions in cooperative organisations.5 They control access to the distribution of subsidised resources – credit, fertiliser, herbicides and planting material6 – and they have often, on the basis of this control, been able to personally invest in a wide range of farm and non-farm enterprises. At Mpanga in Uganda ‘the co-op board … consists of shareholders distinguished by their wealth and education.’ The business of selling cooperative subsidised inputs to non-members or less influential members is said to be extremely profitable (Mullan, Goldman, and Sterns 2008, 105).

In 2011, several ‘smallholders’ could be identified who each sold over 200,000 kilograms of green leaf to Mpanga. In the same year, about 10 slightly less successful members achieved sales of more than 85,000, while a very much larger number (more than 100 members) only sold tiny amounts – less than 150 kilograms – to the Factory. There is a direct relationship between the power of an individual to influence decision-making on Mpanga's Board and the volume they sell, because the latter determines the ownership of shares and, therefore, voting rights. Figure 3 shows that the top decile dominates tea sales to an even greater extent than the biggest sellers are dominating sales to the surveyed coffee cooperatives.7

None of the evidence gathered by FTEPR researchers on the inequality in cooperatives should come as a surprise. More than 100 years ago, rural political economists noted that outsiders – typically urban middle-class outsiders – are remarkably naive in their acceptance, and misleading in their telling, of tales of egalitarian rural cooperatives. This was exactly the kind of tale – ‘a tale invented by kind-hearted people, but a tale nonetheless’ – that Lenin ridiculed (Lenin 1964, 377).

Rural political economy: the costs and (unanticipated) benefits of naivety

Survey data from 2005 and 2006 has found that

the poorest of the poor tend to be excluded from membership in marketing cooperatives in Ethiopia … within a large number of cooperatives, decision-making tends to be concentrated in management committees that are less inclusive of the poorest members of the organization. (Bernard and Spielman 2009, 67)

Similar conclusions have been reached in an analysis of a subset of the same Ethiopian data:

cooperatives should not be seen as means to ensure the participation of the poorest among the poor … cooperatives are rather instruments to reinforce rural elites and the vested order, as they serve to … concentrate market power. (Francesconi and Heerink 2011, 170–171)

The role of these rural elites in Ethiopia and their relationship to the ruling political party have been discussed by Lefort, who argues that in recent years ‘the ruling party extended its institutional authority over all the collective structures of the kebele’ (2012, 692).8 The protracted and failed attempt by Fairtrade to establish an effective and democratic joint body to represent workers on the first certified flower farm in Ethiopia encountered two major problems: an unenlightened farm management and a state insistent on imposing its own norms on, and tight control over, any local representative institutions. The latter problem raises issues of rural political economy that are rarely discussed in the Fairtrade literature, which usually presents certified production as taking place in a political vacuum, where benevolent states will support democratic rural institutions and will distribute resources evenly among photogenic, smiling, smallholder farmers.

The Fairtrade lobby is not alone. Governments, NGOs and donors are all intervening to provide different types of subsidies to the ‘smallholder’ sector, especially if the beneficiaries have formed ‘democratic, membership-based’ organisations, usually on the assumption that rural poverty will be alleviated as a result of their interventions. This approach to poverty reduction was described as hegemonic more than a decade ago (Sender 2003). More recently, some mainstream neoclassical economists have finally identified and begun to query this conventional donor approach (Collier and Dercon 2009, 1). Yet, donor support to ‘smallholder’ groups and the focus on ‘smallholders’ to achieve poverty reduction have not declined.

Like so many other NGOs, Fairtrade has attempted to support and subsidise cooperative groups of ‘smallholder’ producers on the remarkably naive assumption that the benefits of this support are distributed evenly amongst the group.9 This assumption about egalitarian distribution is unwarranted. Besides, it cannot be assumed that the poorest African producers are or can become members of the relatively tiny group of ‘smallholders’ supported by Fairtrade. Interviews conducted with cooperative leaders in Ethiopia and Uganda by the FTEPR research team confirmed that there are large numbers of smallholder producers who have been unable or unwilling to jump the hurdles, excluding them from cooperative membership. Even when smallholders do become members of a cooperative primary society affiliated to a Cooperative Union that has succeeded in obtaining Fairtrade certification for some affiliated primary societies, there is no guarantee that their particular primary society will be able to achieve certification. Groups supported by Fairtrade often exclude poorer local smallholders, and there are many other groups of much poorer producers that are unable to market through Fairtrade channels (Wedig 2012).

Some of these excluded (coffee) producers were interviewed when collecting the FTEPR life's work histories: many said that they depend on emergency consumption credit provided by their employers or the wealthiest of their neighbours. They are forced to repay this credit, at implicitly usurious interest rates, by marketing the harvest of their few coffee trees through their creditor(s), who do not, of course, pay an arms-length – let alone a ‘fair’ – price. They may not be able to afford membership fees of the cooperative, but even if they are paid-up registered members they cannot sell their coffee cherries at the price offered by the cooperative, because they are constrained by interlinked credit, labour and output marketing arrangements.

If production inputs are subsidised, including the costs of land, fertiliser, credit, processing equipment and skill acquisition, or if the output price benefits from a subsidised premium, then it is obvious that the largest producers and sellers will be receiving the lion's share of these subsidies and will decide to invest premium payments to benefit themselves or their own families. For example, if the Fairtrade social premium is spent on facilities at a school regularly attended by leaders' children, but not by the children of the poorest who drop out after a very few years of education, then poor children derive relatively limited benefit.10 Or the social premium may, as at Fero, be spent on an electricity line that only connects the houses of a few relatively wealthy people. At Mpanga, the Fairtrade social premium was used to construct a health clinic, but poor people living nearby who are not currently employed on a permanent basis, i.e. casual workers, must pay a fee to attend this clinic – a fee that many cannot afford. Mpanga has also used the Fairtrade premium to construct flush toilet facilities near the factory, but only senior management has access to these. Such are the realities of the ‘community’ imagined as beneficiaries of Fairtrade. Consumers pay over the odds for certified products, but the stories used to promote this consumption are misleading.

However, that only a few smallholders receive the lion's share of the resources provided by Fairtrade and other external agents, and that the poorest smallholders are effectively denied membership of those cooperatives or farmers' associations that have been allocated subsidies, does not mean that these interventions are failing to reduce rural poverty. Rather, it means that the distributional consequences and poverty-reducing impact of Fairtrade interventions have to be reassessed on the basis of a different set of assumptions and within a different theoretical framework.

The FTEPR reassessment shows that Fairtrade interventions probably do improve the standards of living of some of the poorest rural people, but as an unintended positive consequence of misguided and inefficient interventions. A much greater impact on rural poverty could be achieved if policies and interventions were based on an appreciation of the real as opposed to the imagined mechanisms of rural poverty alleviation, i.e. a less naive or romantic analysis of rural political economy.

Surviving in rural Africa: an uncensored account

The poorest people in the FTEPR fieldwork sites depend for their immediate survival on the wages they receive as casual workers. If their employers were selling Fairtrade-certified tea or coffee (or flowers), then workers usually had to accept inferior wages and working conditions, i.e. other employers selling the same commodities to non-certified markets paid better. For example, female manual agricultural wage labourers working for certified employers were paid only about 70% of the daily wage earned by similar workers in non-certified sites producing tea, coffee and flowers; and they were offered fewer days of employment at this lower wage rate. In general, larger-scale employers were able to offer more days of employment as well as higher daily wage rates (Cramer et al. 2014b).

Much of the literature on Fairtrade and on rural development in Africa ignores the reality of this widespread dependence of the poorest rural people on wage labour incomes.11 As a consequence, there are few attempts to examine rigorously the impact that interventions in the ‘smallholder’ sector are having, or could have in the long term, on poverty reduction through stabilising or increasing wage incomes. While the majority of, or the average, smallholders may never prove capable of generating a significant increase in local wage-earning opportunities, the capitalist members of farmer groups are already beginning to play an important role in poverty reduction, because their output is produced by both local and migrant wage workers from poor rural areas. A substantial proportion of the people surveyed by the FTEPR in some export crop production sites were migrant wage workers from much poorer rural areas, such as Kabale in Uganda or the extreme south of Ethiopia.

The most important subsidies to these rural capitalists have been provided through state intervention and state allocation of resources funded by major donors. Substantial state subsidies have been allocated to Ugandan cooperatives since the early 1950s.12 More recently, at Mpanga for example, the leading shareholders have benefited from large allocations of privatised estate land at below market prices (a parallel to the fire sale prices at which land is being leased to private investors in the Ethiopian flower and coffee sectors). They paid to acquire shares in previously nationalised land using loans granted at subsidised rates of interest. The key assets acquired by the Mpanga shareholders include not only the underpriced estates but also the processing factories, which were rehabilitated before and after privatisation at considerable cost; these costs were met or subsidised by the EU and other donors. The leading Mpanga shareholders also control the distribution of scarce and subsidised fertilisers and herbicides; they often sell fertiliser they have acquired on the basis of subsidised credit for cash profit on the local market. Not only do they dominate the board of shareholders, there is also considerable overlap between the larger smallholder farmers and the salaried management of the factories and estates, providing many opportunities for individuals to appropriate publicly provided resources for private ends.13 Similarly in Ethiopia, the leaders of Fairtrade-certified groups of producers have received major state subsidies, not only through the extremely favourable tax and marketing treatment of cooperatives, but also through their control of, or privileged access to, subsidised inputs provided by bilateral donors, NGOs, and the Corporate Social Responsibility expenditures of multinational corporations such as Starbucks.

Encouraged by Fairtrade organisations, both capitalist members of certified producer organisations and the supermarkets conceal the fact that ‘smallholder’ coffee and tea is produced by wage labourers who earn a pittance.14 In the case of coffee this has been institutionally formalised in the Fairtrade International classification of a ‘smallholder’ commodity, with a distinct set of certification standards for smallholder producer organisations resting explicitly until very recently on the assumption of almost total absence of hired labour. More recently, Fairtrade International standards have been adapted to provide some belated acknowledgement of wage employment in smallholder producer organisations. But the new approach still refuses to examine wages in audits unless a rather large number of workers are employed, setting an arbitrary level of 20 wage workers as the threshold for application of most components of its labour standards.15 FTEPR research has shown how very common it is for farmers to hire fewer than 20 wage workers; it has also shown how common it is for outsiders to undercount the number of wage workers on farms.

Policy conclusions

As argued above, myths about smallholders and cooperatives have had the completely unintended effect of allowing some opportunities for rural accumulation and the expansion of wage labour in crop production. However, if poverty reduction is the main goal, then focused interventions to promote a far more rapid rate of growth of wage labour in export crop production are required. Interventions aimed at cooperatives, such as those discussed in this paper, are neither an effective way of encouraging the rapid development of rural capitalism nor, as a consequence, an effective way of generating rapidly increasing demand for wage labour. Accelerated capitalist development requires discrimination and the targeted use of subsidies, reinforced by an explicit, realistic and publicly debated rationale for the choices of targets.

For example, Fairtrade certification efforts could be shifted towards producers known to make a major contribution to wage employment and to pay relatively high wages; but Fairtrade and donor (or indeed developing country government) support to such capitalist enterprises or to groups of dynamic capitalist farmers should never be granted without a quid pro quo from the beneficiaries and a clearly identified mechanism to discipline them should they fail to meet their side of the bargain.

In other words, Fairtrade, NGOs and other donors investing to reduce rural poverty need to make much greater efforts to monitor capitalist compliance with targets for decent wage employment, as well as with targets for other indicators likely to be correlated with increasing labour demand (direct and induced), including improved yields, rate of growth of output and improved quality. Fairtrade International and others should also explicitly condition their support on political and legislative support for independent trade unions.

There has been little effort to establish Fairtrade certification on several of the most productive coffee and tea estates in both Uganda and Ethiopia, despite their actual and potential contribution to poverty reduction. In the smallholder certified organisations, few if any steps have been taken to monitor rigorously the wages and working conditions of casual and seasonal wage workers, even those seasonal wage workers directly employed by Cooperative Unions; abusive treatment of wage workers is perfectly compatible with continued certification. For example, FTEPR research clearly shows that, on the only Fairtrade-certified estate in Ethiopia (producing cut flowers), workers' basic rights were routinely flouted and management was easily able to evade the half-hearted attempts of Fairtrade certifiers to promote the interests of employees.

Fairtrade auditors need to make a radical break with easily evaded box-ticking techniques and spend more time in the field interviewing significant numbers of workers who have not been handpicked by the management. The paltry number of wage workers interviewed in a recent study of a Fairtrade-certified tea estate in Malawi, for example, is no foundation for learning anything significant about working conditions.16 In the FTEPR study in Ethiopia and Uganda, researchers could not find a single large employer producing Fairtrade-certified tea or coffee whose casual workers had been contacted during a FLO audit.17 However, it was not at all difficult for FTEPR researchers to find young girls, below the age of 14, who had been casually employed by the processing stations owned and operated by Fairtrade-certified cooperatives.