Introduction

This article reveals the changing agricultural and marketing patterns in post-2000 Zimbabwe. The Fast Track Land Reform programme (FTLRP) resulted in reconfigured agrarian relations, bolstered by re-peasantisation (Moyo and Yeros 2005) as a changed agrarian structure arguably imposed new production and commoditisation patterns across the settlement types. Many scholars on agrarian change in Zimbabwe have focused on the land reform process, emphasising its disruptive nature in procedure (jambanja – the violent and chaotic land grabbing) in Zimbabwe (Marongwe 2008; Zamchiya 2012), while analysis of its qualitative outcomes in production and marketing patterns and the associated implications on capital accumulation and class formation for rural Zimbabwe have generally been eschewed.

Preceding the FTLRP, the ‘willing seller, willing buyer’ clause incorporated into the Lancaster House Constitution in 1979 ensured the persistence of the skewed land ownership structure (Stoneman 1988) in which 5252 white commercial farmers owned 47% of the productive land (Moyo 2011a). In the 1980s, geo-political interests (Moyo 2000; Stoneman 1988), the national reconciliation policy (Shonhe 2018), lack of systematic conceptualisation (Sachikonye 1989), combined with the protectionist clauses in the constitution and implementation of the Economic Structural Adjustment Programme, led to demands for the land reform programme to be resisted (Alexander 1994). Moreover, there was resistance to land reform due to ‘diverse interests from the technocratic arms of the state, new black elites, white capital and commercial farmers, donors and external investors’ (Shonhe 2018, 11). The government succumbed to pressure from rural movements including war veterans, traditional leaders and peasants (Sadomba 2008), leading to constitutional amendments in 1990, 1992 and 2000, revoking the willing-seller willing-buyer clause, allowing for compulsory land acquisition and accelerated land reform and resettlement implementation, respectively. Political pressure from the newly formed Movement for Democratic Change may have hastened the FTLRP as the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union–Patriotic Front (ZANU–PF) was defeated in a constitutional referendum in February 2000.

The political context for the agrarian structural reconfiguration is far-reaching given that the timing of the FTLRP take-off was preceded by an unprecedented electoral threat following the defeat of the ZANU–PF government in the February 2000 referendum (Raftopolous 2003; Selby 2006). The launch of the FTLRP also coincided with the emergence of a labour-based political party – the Movement for Democratic Change – in 1999, an unplanned generous payout to war veterans in 1997 and the participation of the Zimbabwe National Army in the Democratic Republic of Congo (1997–99). These political undercurrents fomented resentment that triggered massive local pro-democratic movement resistance and attracted negative global publicity. The accompanying failing political situation therefore precipitated strife across the whole economy epitomised by militant-labour-organised strikes (1997), growth reversals from 1997 onwards, and the stock market and currency crash (1997). To be sure, as Kamidza (2013) observes, from 1999 onwards, the economy lost nearly 50% of gross domestic product and encountered colossal capital flight, huge reductions in private investments and shrinking foreign currency inflows, forcing a tight foreign exchange regime to be introduced.

Inevitably, the economy rapidly became a shadow of its past glory days, with a collapsed manufacturing industry operating at between 4 and 10% of the installed capacity by 2008 (Nyakazeya 2009). From 2000, the FTLRP-induced changes in the level of productivity, a shift in commodity crops under production, from cash to food, the closure of long-standing domestic and international agricultural markets for cash crops mainly due to sanctions and, on a limited scale, to technical issues such as royalty payments for horticultural produce, all negatively impacted on the economy. Second, the liberalisation of the economy from 2008 resulted in changes in the production and marketing of agricultural and non-agricultural produce as well as the intensification of the adverse incorporation of peasants into the global commodity circuits, through primitive capital accumulation (Shonhe 2017). In this period, peasant farmers shifted from food to cash crops; mainly tobacco, cotton and sugarcane.

This article uses empirical data analysis to reveal the changing patterns in production and marketing of agricultural produce. In the main, it reveals that while contract farming has gained prominence following the FTLRP and the post 2008 re-financialisation of Zimbabwe's agricultural sector, this phenomenon does not fully account for the changing production patterns. Its purpose is to reveal how the changing agricultural and marketing patterns in post-2000 Zimbabwe have incorporated rural farmers into local, national and global commodity circuits and how these have shaped agrarian change and have begun to influence economic transformation and political transition in Zimbabwe. The rest of this article is structured as follows: a review of literature on rural agrarian change relations and class dynamics, discussion on methods and data collection, presentation of results, a discussion and conclusion.

Rural agrarian change and class dynamics

As Cliffe et al. (2011) observe, agrarian change involves ‘class reformation’ which, according to Cousins (2013), is a key feature of debates on the classic agrarian question. Some scholars (Lenin 1964; Kautsky 1988) propose the semi-proletarianised agrarian path from a non-capitalist to a capitalist mode of production as opposed to Marx's deterministic transition to capitalism which centred on peasantry dispossessions and extraction of surplus labour through rent, profit and wages (Moyo and Yeros 2005). The semi-proletarianisation thesis posits that small peasants exist alongside large capitalist farming, the former serving the latter, subsidising social reproduction of labour earning low wages. As Moyo (2016, 3) observes, Zimbabwe's transition to the capitalist mode of production cannot be reviewed using the ‘historically deterministic and linear terms’ of Europe and North America as these face the impossibility of reproduction in Africa.

Lenin (1964) identified two paths to agrarian change, the Junker path of the Prussian landlords and the American path of smallholders. Later, Byres (2006) observed the prevalence of this path in Latin America and Asia with a slight variant in Southern Africa (Moyo and Yeros 2005), where large-scale farms work in alliance with transnational capital and are, at times, involved in agro-ecotourism and, more recently, in the expansion of agro-fuel projects. The American path involved the generality of the masses and was therefore perceived as more democratic and broad-based as it created opportunities for a multiplicity of small farms expanding the domestic market. Beyond observations by Lenin (1964) and Kautsky (1988), De Janvry (1981) identified the possibility of other developmental paths, such as the merchant path – modernised medium-sized farms, characterised by absentee management occupied in salaried positions or some petty commodity production. A capitalist path composed of contract-based farmers supported by multinational agribusiness was also observed in Latin America (Ibid.).

Moyo and Yeros (2005) suggested the existence of other trajectories: the state path where the state is involved in land appropriation for nation building, now common in the periphery; the middle-to-rich path of diversified commodity producers engaged in varied on-farm and off-farm activities such as transport, trading and small hospitality services; the rural poor path of masses of fully proletarianised and semi-proletarianised peasants on family plots used for petty production and as social security. The peasants straddle rural and urban centres, and national boundaries, participating in the informal sector, petty trading, craft making and flexibilised employment.

What factors impact on accumulation possibilities? Lenin (1964) posited that land and other means of production, the basis of production and the ability to generate surplus were the most crucial. Akram-Lodhi (1993, 563) specified economic strength to be measured by ‘area cropped, amount of rented-in land, the number of animals, availability of water, quality of soil, quality of seeds and fertilizers, degrees of mechanisation and availability and use of labour’. Other scholars such as Athreya et al. (1987) observed that, besides farm sizes adjusted for irrigation, cropping patterns and size of the family, commercialisation and commodification increased the social differentiation among peasant farmers.

What structure is emerging in Zimbabwe's countryside after the FTLRP? For Moyo (2011b), the FTLRP accentuated the emergence of the trimodal agrarian path where the peasantry, the middle farmers and the large-scale capitalist farmers co-exist. In Moyo's (2011b, 944) view, this agrarian path is ‘based on differences in land size, forms of land tenure, social status of landholders and capacity to hire labour’, agro-ecological potential and technical capacity. Moyo and Nyoni (2013) also identify integration into the world market of various types of farmers as an important variable. Beyond Zimbabwe, Moyo (2016, 4) observes that the trajectory of agrarian change was taking shape in most of the sub-Saharan African countries. In sub-Saharan Africa, Mkandawire (2013) noted that the expansion of the large-scale commercial farms (LSCFs) is a function of non-rural indigenous capital linked to public service, private professionals and entrepreneurs that began to emerge in the 1970s.

The small farmers of the trimodal agrarian structure are characterised ‘by self-employment of family labour towards producing foods for auto-consumption and selling some surpluses, as well as various non-farm and short-term wage labour’, with differentiated capacities to hire in and hire out limited amounts of labour amongst small-scale farmers (Moyo 2011b, 944: Moyo 2016). The second group within the trimodal structure are the middle and large-scale capitalist farmers who ‘have the highest number of wage labour per farm household’ (Chambati 2013, 8), with a few hiring farm managers (AIAS 2007). These farmers hold land which is amenable to market transactions, mainly through leases, and freehold title (Moyo 2011b). The third category is made up of agro-industrial estates mostly owned by large-scale landholders and capitalist enterprises (Moyo 2011a) under freehold title and vertically integrated enclaves, including tourism conservancies and state estates (Moyo 2011b). They hire large amounts of permanent and seasonal labour (Chambati 2011) and rely on an increasing number of outgrowers under contract farming (Moyo 2011b).

More recently, Shonhe (2017) suggested the existence of a poor, middle, middle-to-rich and rich (PMMR) agrarian structure where the middle farmers predominate. In the main, the production patterns suggested by the PMMR indicate that land size is not a major factor in production and accumulation processes; instead, average maize output, average tobacco output, average cattle holdings, number of months maize harvest will last and family labour hired out tend to influence agrarian relations in contemporary rural Zimbabwe. To this end, the reinvestment into agricultural production of the proceeds from commodity sales was identified as the most significant variable driving accumulation and class formation in rural Zimbabwe. This is contrary to the widely held view that contract farming is predominating (see Moyo and Nyoni 2013; Sakata 2016; Sachikonye 2016; Scoones et al. 2017).

Methods and data analysis

This article is based on empirical research across four ecological regions and five settlement types in Hwedza District in Mashonaland East Province. The district has five settlement types and four natural agro-ecological regions (NR):1 small-scale commercial farms in NRIV, communal area in NRIIb and NRIII, old resettlement area (ORA) in NRIIb, A1 (villagised plots) in NRIIb and A2 (medium-scale farms) in NRIIa receiving varied rainfall amounts and therefore suitable for differentiated cropping and livestock production. Hwedza District has sandy loam soils, suitable for tobacco, cereal crop production and livestock farming. Using the mixed method, this unique case study involving 230 structured interviews and 20 (purposively selected) unstructured interviews in Hwedza District on agricultural production, labour relations and social reproduction dynamics sheds light on agrarian change after the FTLRP. Respondents were randomly sampled within each cluster in the five wards targeted for this research. To select the households for structured interviews, plot numbers for all the households in a targeted area were put in a hat from which a targeted 50 were picked one after the other until the required total number was reached for each of the five clusters.

The targeted number of respondents of 50 per cluster enabled effective comparative analysis for communal areas (CA), small-scale commercial farms (SSCF), old resettlement areas (ORA) and FTLRP farms (A1 & A2) types. However, non-residency on the farms in the A2 farms limited the number of households interviewed to only 30. Careful contact and references were used to ensure that the few people identified for unstructured interviews had detailed knowledge of the dynamics of agrarian change in Zimbabwe. To aid the process, themes were established from qualitative data and these aided quantitative data interpretations.2

Agricultural financing: access to credit, contract farming and self-finance

Agricultural financing is a key enabler in the inputs and outputs markets for farmers across the settlement types, yet access to bank credit is generally low in Zimbabwe. The study reveals that only 1.3% of the interviewed farmers accessed credit in 2013 and 2014. Even though only 6.2% of the A2 farmers accessed credit in Hwedza District, they had the highest number of farmers receiving credit over the period. At least 13% of the households interviewed faced challenges after attempting to access credit, with 23.9% of these coming from the ORA and 21.9% from A2. Households faced differentiated challenges across the variegated settlement types. Of the interviewed households who indicated that they faced challenges, 44.4% expressed lack of collateral security and 48.1% indicated that they failed to meet other bank requirements.

Most of the farmers (87%) who did not encounter problems never approached the banks. Agricultural funding arrangements for farmers in Hwedza District were affected by the prevailing macro-economic conditions associated with extreme capital and credit scarcity amidst limited government budgetary capacity and funding options (Mkhize and Moyo 2012). A study by Scoones et al. (2010) in Masvingo Province also revealed that farmers were facing difficulties in accessing credit, in particular of the A2 type. Farmers in Hwedza District faced challenges in accessing credit funding like those generally affecting farmers across the country in the post-2000 period, despite the liberalisation of the economy and the introduction of the multi-currency system (see also Murisa and Chikweche 2015).

The re-financialisation of the agrarian sector after 2008 has led to increased production of cash crops by smallholder farmers across the different types of settlement. This is a much-debated matter, with some scholars observing that contract farming is increasingly prevalent (Sachikonye 2016; Sakata 2016; Scoones et al. 2017) and combines with patronage-linked government support to drive accumulation in the countryside (see Zamchiya 2012). Sachikonye (2016) observed that contract farming became the dominant modality for funding the production of tobacco because of the government's inability to fund it after 2000, the introduction of the multi-currencies in 2009 and the emergence of Chinese capital through TianZe under the ‘Look East’ policy.

Little and Watts (1994, 9) define contract farming as ‘a form of vertical integration between agricultural producers and buyers (exporters, agro-processing companies or retailers) at the end of the value-chain’. It involves the supply of farming inputs (fertilisers, chemicals, coal, seeds, labour finance), management services and markets for the produce by international and domestic merchants, often operating through local banks. Through stop-orders, farmers make payments upon delivery of tobacco to the merchant's auction floors. More recently, for the government-mediated command agriculture, the stop-orders are handled through the resuscitated Grain Marketing Board where cereal foods are delivered.

Notwithstanding the upsurge in cash crop output, mainly tobacco, the current boom in contract farming fails to account for the emerging production, accumulation and social differentiation patterns in Zimbabwe. Moreover, Sakata (2016) observed that in Marondera District, while 70% of tobacco farmers relied on contract farming, 26% received family support. At least 72.3% of the contract farmers felt the inputs (particularly fertilisers) supplied by contract companies were inadequate and needed to be supplemented. Consequently, 34% of the interviewed farmers advised that they intended to pull out of tobacco farming in the following season, mainly due to unstable prices (Sakata 2016, 103). Scoones et al. (2017) also confirmed that in Mvurwi, 25% retain contract tobacco farming while the rest choose the independent farming option. They also emphasised the need for a broader analysis that considers the role of on- and off-farm incomes, as agricultural produce was viewed to be dominant in shaping social differentiation in Zimbabwe.

However, our research in Hwedza District revealed that 35.2% of the interviewed households grew tobacco, yet only 33.3% of these or 11.7% of the interviewed households accessed funding through contract farming during the 2014–15 farming season. Sixty per cent of the A2 farmers involved in tobacco production access contract-based funding, compared with 50% CA, 35% A1, 33.3% ORA and 25.9% SSCF. The A1 sector has the highest percentage of farmers involved in growing tobacco (56.5%) compared with SSCF (50.9%), ORA (45.7%), A2 (15.6%) and CA (3.8%). Through contract farming, domestic and international capital are significantly involved in tobacco farming and marketing, thereby shaping peasant agricultural production, as we shall see in section to follow.

Capital flight after the FTLRP resulted in reduced funding options for farmers for both food and cash crops. Constrained by the unfavourable macro-economic conditions and declining funding options, cash crop merchants ‘who needed assured commodity supply lines engaged in contract farming particularly from 2004’ (personal interview, TM, 5 July 2016). At the same time, big multinational companies, such as the China Tobacco Company, came in to support the production of the tobacco to meet their annual demand (personal interview, GM, 19 July 2016). Contract farming is more prevalent in traditional cash crops such as tobacco, sugarcane (as outgrowers), soya beans, cotton (in some parts of the country from 2008), and rarely in livestock and food crops, following the liberalisation of the economy, mainly the removal of local commodity marketing restrictions. Moyo et al. (2014) observed that the ‘re-insertion of capital’ re-oriented agricultural production towards external dictates. Pre-2000, bank credit was targeted at these crops but also included coffee and livestock farming. In earlier efforts, immediately into independence, the Agricultural Finance Corporation expanded the extension of loans to the peasantry but defaults and auctioning of property were rife (Chimedza 1994).

Our case study shows that farmers tend to exit contract farming once they are able to self-finance, as part of their resistance to unstable prices. Smallholder farmers complain about how the contracts bestow decision-making powers on production and marketing to the merchants. Smallholder farmers also resist their conversion into ‘disguised workers’ for the merchants and ‘disguised landowners’ as they tend to lose control of land-use decision making during the life of the contracts (interview, SM, 27 July 2016). Moreover, the contracts tend to shift all the risk in weather uncertainty to the smallholder farmer, such that failure to meet repayment obligations due to low productivity in drought years has led to some farmers fleeing into neighbouring countries to avoid loss of property, including cattle, as contracting merchants seek to enforce the agreements.

Given that access to credit and contract farming among the interviewed households in Hwedza was low in 2015, farmers relied on off-farm income to finance crop and livestock production, with 8% relying on building and 4% on vending of clothes. Overall, these sources of income have low percentage contributions to the total farming requirements across the farming types, indicating that the farmers have other sources of funding as shall be revealed below. Despite reliberalisation of the economy, dollarisation and an introduction of multi-currency from 2009 (Moyo et al. 2014), no overall improvement in access to credit was achieved by rural farmers in Hwedza District, across the settlement types. As a result, rural farmers are engaged in various off-farm and non-agricultural activities and petty commodity trading to augment agricultural production.

Across settlement types and agro-ecological regions, farmers engaged in increasingly diversified activities to earn income for investment in farming and for social reproduction. Figure 1 shows that households were mostly engaged in the construction business (bricklaying, building and thatching) in 2015. Some households are also involved in vending of clothes and motor mechanics among other activities. The highest-earning off-farm activity recorded by the study was the transport business, an average of US$3180.00 per annum compared with bricklaying – US$950.79, building – US$1616.11, woodcarving – US$1026.67, small tuck-shops – US$1050.00 and operating retail shops – US$2675. Households relying on off-farm activities are therefore better positioned to finance crop and livestock production as they are more capable of accessing the requisite farming inputs.

Notwithstanding the viability of contract tobacco farming (Masvongo, Mutambara, and Zvinavashe 2013; Sachikonye 2016), Zimbabwe's reconfigured agrarian sector is highly dependent on reinvestment and personal savings for financing. Overall, in 2015, 52.6% of the households in Hwedza District relied on proceeds from agricultural sales to fund agricultural activities, 26.3% used personal savings and 10.5% relied on diaspora remittances. Across the settlement types, 68.1% of the inputs were secured from local agro-dealers and 6.9% from CA agro-dealers, indicating the prevalence of cash sales and reinforcing the reliance on agricultural sales proceeds, given the limited banking facilities and access to credit in rural Zimbabwe.

Sources of funding, by settlement types, 2015. Source: Author, compiled from Hwedza District survey data, 2015.

Sources of funding are differentiated across the settlement types. For instance, 80% of A1 and ORA used proceeds from agricultural sales, with 71.4% of the SSCF and 100% of the A2 farmers relying on the same source (Figure 2). At least 61.5% of the households in the CA relied on personal savings compared with 23.1% relying on diaspora remittances. Compared with the other types of settlement, CA did not receive any income from the sale of proceeds due to low agricultural output, dominance of auto-consumption and exclusion from participation in the commodity chains. That CA mainly relied on personal savings (61.5%) is indicative of dependence of the households on petty commodity production outside agricultural activities.

Overall, agricultural funding is being driven by reinvestment of agricultural sales proceeds and personal savings, differentially among the small commercial farmers. This confirms the predominance of ‘accumulation from below’ and an increased role for ‘national capital’ as opposed to international monopoly capital accessed through contract farming. This is an important revelation in that it brings to the fore new possibilities for Zimbabwe's agrarian transition, driven by smallholder and medium-scale farmers.

Land and input use: crops and livestock

The FTLRP distributed better-quality land in more productive agro-ecological regions of the country to otherwise land-short peasants, thus allowing them to expand production (Moyo and Nyoni 2013). This has triggered social differentiation and new class formation across the countryside and inevitably accumulation from below, leading to consolidation of farm lands by an emergent capitalist farming class who have expanded their operations. In Zimbabwe, expansion has been enabled through land leases and rentals (Shonhe 2018). This has led to the emergence of a semi-proletariat or an agrarian underclass socially reproducing itself from wage labour, petty commodity trade and peasant farming in the countryside.

A critical variable in measuring agricultural productivity is land utilisation, beyond the total land accessible to the farmers. To illustrate the point, whereas surveyed households had access to a total of 7331.15 ha of land, an average of 34.26 ha per household, and 7077 ha (96.53%) being arable, representing an average of 33 ha per household, only 9.36% of the land was under crop, with an average of 3.2 ha per household in 2015 (Table 1). Disaggregating the survey data for the middle farmers shows that, notwithstanding SSCF having access to the highest-average arable area of 93.1 ha compared with 48.6 ha for the A2, the average cropped areas stood at 3.5 ha and 7.6 ha respectively.

| Model | No. | Total area per sector | Total area available | Arable land | Average arable land | Total cropped area | Average cropped area | Irrigated area | Average irrigated area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 46 | 348.2 | 7.6 | 263.5 | 5.7 | 84.7 | 1.8 | 0 | 0 |

| % of arable | 4.7 | 75.67 | 32.1 | ||||||

| SSCF | 51 | 4924 | 96.5 | 4747 | 93.1 | 177 | 3.5 | 0 | 0 |

| % of arable | 67.17 | 96.41 | 3.73 | ||||||

| A2 | 26 | 1462.5 | 56.3 | 1264 | 48.6 | 198.5 | 7.6 | 4.5 | 0.17 |

| % of arable | 19.9 | 86.4 | 15.7 | 2.3 | |||||

| ORA | 45 | 428.2 | 9.5 | 371.4 | 8.3 | 56.8 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 |

| % of arable | 5.80 | 86.7 | 15.3 | ||||||

| CA | 46 | 168.25 | 3.7 | 85.85 | 1.9 | 80.3 | 1.7 | 6.5 | 0.14 |

| % of arable | 2.3 | 93.54 | 93.54 | 8.56 | |||||

| Total | 230 | 7331.15 | 34.26 | 7077 | 33 | 686.38 | 3.2 | 13.31 | |

| % of arable | 100 | 96.53 | 9.69 | 1.94 |

Source: Author, Hwedza District survey data, 2015.

Note: Area is in hectares.

Similarly, for smallholder farmers, whereas the A1, ORA and the CA farmers had access to an average of 7.6 ha, 9.5 ha and 3.7 ha of total arable land, respectively, the cropped areas stood at an average of 1.8 ha, 1.3 ha and 1.7 ha respectively. In comparative terms, the communal areas had the highest land utilisation levels of 93.54% of the arable land, compared with the A1 – 32.1%, A2 – 15.7%, ORA – 15.3% and the SSCF – 3.73%. While disproportionate land shortage in the CA and poor climatic conditions in the SSCF (situated in NRIII and NRIV) are material to land utilisation for crop production, this latter is negatively correlated with land access.

Moreover, access to irrigation infrastructure is not uniform across the settlement types. Among the surveyed households, irrigation infrastructure was found in A2 and CA only. A2 farms had a total of 4.5 ha and an average of 0.17 ha per household under irrigation compared with CA's total of 6.5 ha, an average of 0.14 ha of irrigated lands per household. Agricultural production trends are therefore a function of the cropped land and access to irrigation infrastructure, while the FTLRP increased access to land by households, increases in the cropped land are a function of access to capital, including cattle and farming equipment.

Agricultural production in the pre- and post-independent period reflected land ownership inequities where the smallholders had access to poor lands in low rainfall areas and were slow in adopting green revolution inputs (Weiner 1988). The introduction of government subsidies to CA farmers in the 1980s, in the form of free handouts of seed and fertilisers, resulted in a boom in maize production from 1980 to 1984 (Masst, 1996; Weiner 1988) and a threefold hike in cotton production between 1977–80 and 1988–91 (Masst 1996). However, the average productivity in maize remained higher among LSCFs (4726 kg/ha) compared with 695 kg/ha for the African smallholders.

The FTLRP of 2000 reconfigured agrarian relations in a significant way. Although Zimbabwe produces over 20 major and minor crops for food and cash purposes (Moyo et al. 2009), evidence from Hwedza District shows that there are five major crops (maize, sugar beans, tobacco, groundnuts and tomatoes) produced by most households, across agro-ecological regions and settlement types. Using the two key crops, maize and tobacco, the study revealed that agricultural production patterns in Hwedza District are based on settlement type and class. The poor farmers produce food crops more for auto-consumption while the richer target profit-making. For instance, in the 2014–15 farming season, 77.4% of the households across the settlement types and agro-ecological regions produced maize for their own consumption in 2015, while 13.9% produced for profitability purposes and 6.2% did not grow maize. Within the CA, 97.9% of the surveyed households confirmed growing maize for consumption while 2.1% grew the crop for sale. In the SSCF, 84.6% of the households, 82.9% in A1 and 71.8% in ORA grew maize for consumption, while 55.2% of the A2 households grew for sale, with 31% of the households growing the crop for their own consumption.

The 2014–15 maize production figures show differentiated production levels among farmers. CA households are equally divided into four groups, producing less than 250 kg, 501–750 kg, 751–1000 kg and 2501–5000 kg of maize per annum. Of the A1 households, 33.3% produced between 751 and 2500 kg of maize per annum, compared with 75% of the SSCF which produced between 1001 and 2500 kg, 55% of the A2 over 5000 kg, and two groups comprising 37.5% each of the ORA, one producing 751–1000 kg and the other 2501–5000 kg.

The lowest annual tobacco yield per household of less than 250 kg was recorded in the SSCF, falling under NRIII and IV and subject to poor rainfall patterns and therefore at times low crop yields. At least 50% of the A2 households produced between 1001 and 2500 kg, while 25% of the households produced over 5000 kg of tobacco. A2 outperformed all other farm types in total yield per household while no CA households produced more than 1000 kg of tobacco in 2015. All in all, agricultural production is differentiated across the settlement types for both maize and tobacco crops for varied reasons; however, the A2 farmers are performing better than the others.

The use of agricultural inputs such as seeds, fertilisers and chemicals is heterogeneous but aligned to the settlement types established in the pre- and post-independence periods. The use of retained seed in 2015 was more prominent among the A1 households at 24%, compared with the SSCF at 19%, A2 at 16%, ORA at 13% and CA at 11% (Table 2). The retained seeds common in the ORA farms were deemed to perform as well as the certified seeds even though they do not go through the chemical treatment processes. Regarding the use of certified seed and fertilisers, the SSCF have the highest levels of 98% and 100%, while the CA have the lowest levels of 60% and 85%, respectively. The use of fertilisers and chemicals for the newly settled farmers (A1 and A2) was above 81% and 91% respectively. The impact of certified seed and fertilisers on productivity for both food and cash crops was therefore generally high. In some cases, some households used a combination of certified and retained seed, due to limited access to certified seed consequent to the high input prices.

| Model | Use retained seed | Total | Use certified seed | Total | Use fertilisers | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||

| A1 | No. | 11 | 35 | 46 | 40 | 6 | 46 | 43 | 3 | 46 |

| % | 24 | 76 | 100 | 87 | 13 | 100 | 94 | 7 | 100 | |

| SSCF | No. | 10 | 43 | 53 | 52 | 1 | 53 | 53 | 0 | 53 |

| % | 19 | 81 | 100 | 98 | 2 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | |

| A2 | No. | 5 | 27 | 32 | 26 | 6 | 32 | 29 | 3 | 32 |

| % | 16 | 84 | 100 | 81 | 19 | 100 | 91 | 9 | 100 | |

| ORA | No. | 6 | 40 | 46 | 35 | 11 | 46 | 45 | 1 | 46 |

| % | 13 | 87 | 100 | 76 | 24 | 100 | 98 | 2 | 100 | |

| CA | No. | 6 | 47 | 53 | 32 | 21 | 53 | 45 | 8 | 53 |

| % | 11 | 89 | 100 | 60 | 40 | 100 | 85 | 15 | 100 | |

| Total | No. | 38 | 192 | 230 | 185 | 45 | 230 | 215 | 15 | 230 |

| % | 17 | 84 | 100 | 80 | 20 | 100 | 94 | 7 | 100 |

Source: Author, Hwedza District survey data, 2015.

The government support programme is the main source of inputs and accounted for 33.3% of the households who accessed seed in CA, 24% for A1, 11.8% in ORA, 9.5% in A2 and 7.4% in SSCF. Whereas government offered support for 16.2% of food crop production in 2015, no government support went towards cash crop production during the same year. All in all, 7.4% of the households growing tobacco relied on contract farming as a source of basal fertilisers. Most of the households relied on their own resources, mainly from the sale of agricultural produce, and bought their inputs from local traders on a cash basis. Overall, the CA received the highest level of government support in 2015, at 17.5%, mainly for food crops.

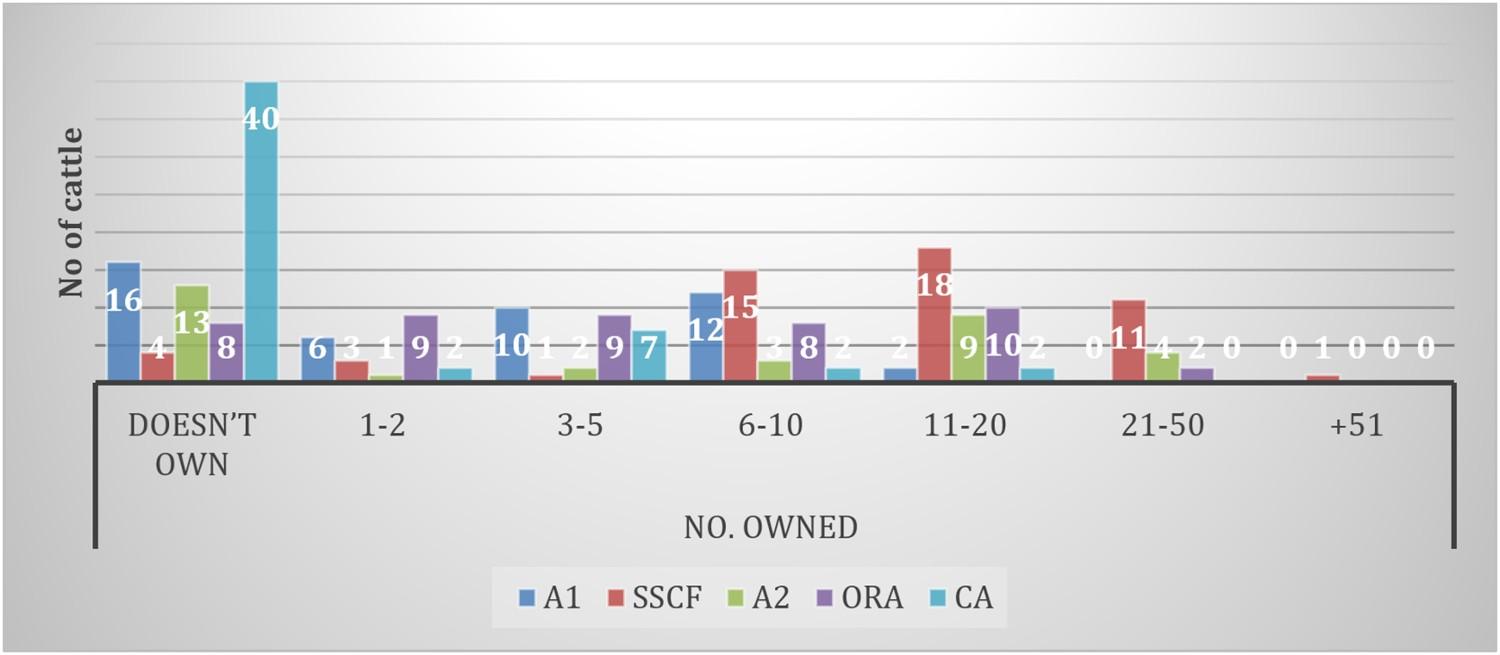

Cattle ownership is a critical factor for agricultural production and capital accumulation for rural farmers, and for shaping social differentiation. However, empirical evidence from Hwedza District shows that in 2015, 35.2% of the households interviewed across settlement types and agro-ecological regions did not own cattle. At 40%, CA farmers constituted the highest percentage of families with no cattle holdings, while some A2 farmers (13%) and ORA farmers (8%) also held no cattle stock (Figure 3). The biggest number and percentage of households owning cattle was the SSCF at 94.3%, compared with the lowest of 24.5%, in the CA.

Livestock production by settlement models, 2015. Source: Author, Hwedza District survey data, 2015.

Overall, 17.8% had between 11 and 20 cattle, 17.4% owned between 6 and 10 cattle and 7.4% owned between 21 and 50 cattle. The highest category of cattle ownership in CA was between 3 and 5 cattle across seven households, representing 13.2% of the CA households interviewed. While the ownership of cattle was differentiated, the medium-scale farmers (SSCF and A2) owned more cattle compared with smallholder farmers (CA, ORA and A1) due to differences in land sizes and location in terms of agro-ecological regions, with the SSCF and A2 being more ideal for livestock farming owing to bigger land sizes available. As Table 1 shows, this seems to give an added advantage for farmers in SSCF and A2 as they can till bigger land sizes, notwithstanding that these farmers tend to have greater reliance on tractor power for tillage.

Crop and livestock marketing channels

The reconfigured agrarian structures created new marketing patterns for food and cash crops. Prior to the FTLRP, the liberalisation of agricultural markets drastically reduced the accessibility of government marketing boards, research and extension services by 1995 (Moyo 2000). The liberalisation of agricultural commodity markets also resulted in the removal of pre- and post-harvest commodity price announcements which had the effect of guaranteeing a minimum price, thereby enabling planning by the farmers. Furthermore, the privatisation of the marketing boards resulted in the creation of intermediary traders in agricultural commodity marketing, which tended to undermine agricultural viability.

While the immediate post-independence period benefited from improved marketing services associated with the construction of roads, introduction of trucks for transport services and the construction of Grain Marketing Board (GMB) depots (Masst 1996), the post-FTLRP experience was the complete opposite owing to the breakdown of infrastructural support for the farmers. Nonetheless, the reliance on specified markets differed along settlement types and crop types over the period studied. The marketing of maize changed in all the settlement types. Overall, dependence on the local/village market dropped from 42.3% in 2013 to 28.6% in 2015. This was the result of, first, market liberalisation introduced by the Government of National Unity and, second, the reversal of the collapsed market situation that ensured greater market participation by the rural farmers. Similarly, the reliance on the nearest urban areas for marketing increased from 7.7% in 2013 to 20% in 2014 but dropped to 14.3% in 2015.

The use of the state marketing boards slightly increased from 34.6% in 2013 to 35.7% in 2015, while on-farm sales to intermediary traders increased from 3.8% in 2013 to 14.3% in 2015. Reliance on local/village markets increased from 75% in 2013 to 80% in 2014 but reverted to 75% in 2015 for the SSCF. The use of the state marketing board dropped from 55.6% in 2013 to 22.2% in 2015 for A2, while that for the SSCF dropped from 25% to 0% in 2015. The 2015 grain output marketing data show that there was greater reliance on the state marketing board by the ORA at 62.5% and by the CA at 80%.

The Zimbabwean market consumes all the maize produced annually. All in all, A2, SSCF and A1 farms are more integrated into the commodity markets compared with the ORA and the CA, in such a way that newly resettled farmers and the SSCF tended to avoid the GMB compared with the ORA and the CA. The changes in marketing trends were a response to the economic conditions in the country, reflecting the level of participation of the different types of farmers in the outputs markets. The GMB has lost its monopoly over the marketing of grain foods, mainly because of its history of failure to pay farmers for delivered grains, either in time or, as in some cases, ever.

In Hwedza District 66.7% of tobacco output was sold through the auction floors and the balance through contracting merchants for the marketing year 2013–14. More A1 farmers grew tobacco under contract farming compared with the other settlement types. Whereas 35.2% of all the interviewed households sold under contract farming, national data for 2015 show that 77% of the crop was marketed through contract farming with 22 merchants purchasing 152.3 million kg out of a total of 198.95 million kg (TIMB 2015).

However, both markets are integrated into the global commodity circuits as most of the tobacco is sold to international traders, through TianZe, British American Tobacco and Alliance One International, and through the Mashonaland Tobacco Company (personal interview, AM, 3 July 2016; Sachikonye 2016; Scoones et al. 2017). Over 95% of the tobacco is exported after semi-processing, mainly to China, where 52% was shipped in 2015, up from 43% in 2014. The EU and Africa imported 17% of the crop each. The survey also revealed the prevalence of sales through makoronyera (dealers) which Sakata (2016) identified as a form of resistance to unfair pricing and exploitation by global capital by the farmers. In the main, BAT exported to its sister companies in South Africa where cigarette manufacturing is carried out, even though the company has capacity to manufacture cigarettes in Zimbabwe (personal interview, MN, 14 July 2016, Harare). Our observations also revealed that BAT South Africa exports some cigarette brands back into Zimbabwe.

The sale of cattle and other livestock such as pigs is highly limited in Upper Hwedza District where households are more involved in crop production owing to the favourable climatic conditions. However, animal husbandry is a worthy enterprise in Zviyambe where 40.1% hold a minimum of 10 cattle per household. Zimbabwe's NRIV is generally suitable for livestock farming and, as a result, Zviyambe thrives in this sector. The marketing channels are both local and national. As a farmer in Zviyambe noted:

We have local buyers to whom we sell our cattle whenever we need to raise funds for our children's school fees, farming inputs and any other household needs. The buyers either resell to local butcheries, schools and to urban abattoirs. (Personal interview, MM, 7 May 2016)

The cattle and pig sales by A2 farmers are mainly to finance crop farming inputs purchases. The proceeds from cattle and pig sales are also applied towards the social reproduction for rural households and for capital accumulation in the form of farm infrastructure and farming assets and equipment. In the main, cattle are held as a store of value for the farmers (Sakata 2016) as farmers are disdainful of opening bank accounts.

Accumulation from below?

This study sought to answer the question: how have the reconfigured agrarian relations altered or maintained agricultural financing, production and marketing patterns in post-2000 Zimbabwe? This article revealed that there is limited access to bank credit with farmers facing a wide range of challenges in securing bank finance. As a result, smallholder farmers across the settlement types resort to contract farming in Hwedza District, this now representing 11.7% of agricultural financing, mainly for tobacco farming. Tobacco contract financing linked to domestic capital and international capital now predominates, as banks avert credit risk associated with unsecured funding owing to weak collateral security and prefer to advance money to big corporates who lend on to farmers.

However, contract farming does not fully account for the financing of agricultural production in Zimbabwe's countryside, particularly in the post-2008 period. On the contrary, smallholder farmers also self-finance using sales of agricultural produce, personal savings from non-farm income and diaspora remittances, which constitute 89.3% of funding overall. Farmers who perform better in one season are likely to perform better in the following seasons as the cropping and livestock proceeds are generally reinvested. Contract farming is also applied as a start-up facility, quickly exited as soon as farmers have secured agrarian surplus which is reinvested in the following seasons. The reliance on contract farming and proceeds from agricultural sales and diminished state capacity which curtails patronage-linked support has resulted in the development of a new breed of independent smallholder farmers whose links to the ruling elite are limited. These farmers are equally de-linked from the opposition forces or urban-based social movements. However, the extent to which self-finance can complete an ongoing agrarian transition remains to be fully investigated.

Regarding government support for agricultural production, this has tended to favour the smallholder farmers in the CA, ORA and A1, targeting maize production as part of the government's welfarist and food security targets, but such support remains very low (11.1%). Crop and livestock production patterns reflect reliance on sales from proceeds from the previous seasons, save for the CA where personal savings from non-farm activities predominate, indicating the prevalence of the semi-proletarianised labour and petty commodity trading and limited commoditisation of the CA. Moreover, an independent middle farmer class is emerging with minimal ties to the state and capital with significant political ramifications. With limited patronage networking, an emerging middle farmer class can potentially begin to drive voting patterns and achieve political change based on its financial and social positioning in rural Zimbabwe. Moreover, the shifting power relations emanating from changes in class dynamics linked to tobacco farming across settlement types may begin to secure these farmers a voice in land management, and the input and output markets if they can organise from below.

Nonetheless, increased reliance on proceeds of agricultural produce sales indicates increased commodification of the farmers within the local markets and the prevalence of accumulation from below. The high prevalence of localised marketing of agricultural produce indicates the slow recovery of the agricultural output markets, especially for maize. The tobacco output market remains solid in both the auction floor and contract farming and proceeds thereof are driving agricultural production for the rural farmers in Zimbabwe. The sale of livestock is an important source of income for crop production and social reproduction for the middle-scale farmers (SSCF and A2) who own larger sizes of herds of cattle.

The over-reliance on own proceeds by farmers discounts the possibility of international capital-led and state-led accumulation trajectory and agrarian transition in rural Zimbabwe. This is contrary to Bernstein's (1996/1997) view that the agrarian question of capital has disappeared. Instead the home market is on the revival and is being driven by reinvestment of agrarian surplus. Moreover, the increased use of off-farm income indicates broadening strategies connected to firming up peasant agency. Faced with uncertain prices for agricultural commodities and unfair contract farming arrangements, farmers resist this by way of diversifying into petty commodity trading and agricultural self-financing. Land utilisation is very low across the settlement types. Differentiated access to capital rather than climatic variations and politics drives agricultural production and accumulation in rural Zimbabwe. While the full dynamism of command agricultural production is still to reveal itself, a new dynamic is in the offing which may further propel the reconfiguration of agrarian relations in Zimbabwe. This government-mediated contract farming is boosting the production of food crops which feeds into the home market, ensures food sovereignty, reverses the extroverted nature of the economy and therefore can potentially ignite a reindustrialisation path for Zimbabwe.

Conclusions

The effects of capital flight experienced from 2000 to 2008 continue to impact negatively on funding options for farmers despite the re-insertion of capital from 2009. While contract farming is increasingly dominating, its scale remains low and in some cases exaggerated, taking into account the total financial requirements for agricultural revival. Smallholders resort to self-financing using agricultural sales proceeds, yet its potential for sustainably driving agricultural development to its full potential remains largely understudied. Equally, the implications for an agrarian transition as theorised by Byres (2016), and revealed by Oya (2013) elsewhere, have not been explored for Zimbabwe. Evidence from Hwedza District presents this opportunity (Shonhe, forthcoming).

However, it remains important to investigate further how far the peasantry is inserted into the global commodity chains through increasing contract farming in Zimbabwe. The differentiated funding, production and marketing patterns within and across the agrarian structure do not entirely follow the settlement types identified and classified here. The unravelling capital accumulation trajectory requires re-thinking (Ibid.). The political implications of the changing production and marketing patterns, mode of accumulation and the resulting class formation and social relations are far-reaching, yet they are barely comprehended by some social movements advocating an egalitarian society and political formations contesting for power. This limited understanding and infusion of the agrarian question into contemporary struggles has revised and narrowed the definition of the national question to a point of becoming hollow.