Introduction

I would like for us to speak about another pressing issue: the issue of debt, the question of the economic situation in Africa. It is an important condition of our survival, as much as peace. […] We think that debt has to be seen from the perspective of its origins. Debt’s origins come from colonialism’s origins. Those who lend us money are those who colonized us. […] Debt is neo-colonialism, in which colonizers have transformed themselves into ‘technical assistants’. We should rather say ‘technical assassins’. […] We have been indebted for 50, 60 years and even longer. That means we have been forced to compromise our people for over 50 years. Under its current form, controlled and dominated by imperialism, debt is a skilfully managed reconquest of Africa, intended to subjugate its growth and development through foreign rules. Thus, each one of us becomes the financial slave, which is to say a true slave, of those who had been treacherous enough to put money in our countries with obligations for us to repay. (Sankara 2019[1987])

Chinese overseas lending has been infamously branded as ‘debt trap diplomacy’ (Chellaney 2017) and politically instrumentalised by the Trump administration and other hypocrites in the West. The latter have been quick to accuse China of leveraging its influence in Africa through loans, whilst they have usually remained dead silent when it comes to the complicity of Western capital in the systematic underdevelopment of the continent. There have since been commendable efforts to demystify the ‘debt trap’ narrative and to shed light (by means of more reliable data) on a topic that is complicated by the opacity pertaining to African debt exposure to China (see, for instance, Horn, Reinhart, and Trebesch 2019; Kratz, Feng, and Wright 2019; Bräutigam, Huang, and Acker 2020). Bräutigam (2020a) has convincingly critiqued the rise of the debt trap ‘meme’, which has been employed to delegitimise Chinese involvements in Africa, quite frequently on the basis of false figures and alleged asset seizures. Meanwhile, there is an entire canon of reports, commentaries and scattered peer-reviewed literature that has engaged in ‘Debunking the myth of “debt-trap diplomacy”’ (Jones and Hameiri 2020), revealing the ‘Realities of Chinese development finance’ (Singh 2020) and conveying ‘The truth about Africa’s “debt problem” with China’ (Kazeem 2020).

Whilst acknowledging the ‘fact-finding’ advances made and the discursive corrective developed by scholars engaged in countering the ‘debt trap’ narrative, this article calls for a critical engagement with structural causes for the recurrence of Africa’s debt issue. It is argued that locking African and other peripheral economies into periodic cycles of debt financing, debt distress and structural adjustment is a tendency inherent to global capitalism. This article first points to epistemological differences that characterise the debt debate in China–Africa studies. Subsequently, it is argued that debt has been a prime technology of capitalist power that has been systematically used to extract African surplus. The next section problematises how neoliberal institutions, policies and development paradigms have fostered recurrent debt cycles and suggests avenues for a critical research agenda on Africa’s indebtedness. The article concludes that a ‘united front against debt’ needs to question the very fundamentals of global capital accumulation – in theory and in political practice.

China–Africa studies and the debt issue

The debt debate in China–Africa studies has exposed widespread ‘fake news’ aimed at stirring up anti-Chinese sentiments. More reliable data on African debt owed to China has helped immensely to put Chinese lending into relation to other sources of debt finance. After all, Chinese lenders ‘only’ owned 22% of external debt of African low-income countries in 2018, with sovereign debt portfolios and the Chinese shares in them varying significantly across the continent (Bräutigam, Huang, and Acker 2020). By implication, it has become clear that political and economic contexts and modes of governance matter greatly and that the extent of debt exposure has been dependent not least on the providence (or lack thereof) of African decision makers (see DeBoom 2020). There is evidence that in some countries currently in debt distress, such as Kenya and Zambia, political elites have engaged in reckless borrowing to secure re-election and/or serve vested interests (Taylor 2020; Zajontz 2020).

There have been epistemological and (meta-)theoretical differences in analyses of debt in China–Africa relations. The literature can be broadly clustered with the help of Cox’s distinction between ‘problem-solving’ and ‘critical’ social science. On the one hand, scholars have focused on the commendable goal of ‘getting the numbers right’ and have provided largely descriptive accounts of Chinese lending in Africa (see, for instance, Bräutigam 2019; Jones and Hameiri 2020; Singh 2020; Brautigam and Acker 2021). This scholarship is ‘problem-solving’ in the sense that it ‘takes the world as it finds it, with prevailing social and power relationships and the institutions into which they are organized, as the given framework of action’ (Cox 1981, 128). Epistemologically, it stands in the tradition of what Cohen described as the ‘dominant version of IPE [international political economy] (we might even say the hegemonic version)’ that follows neo-positivist principles and empiricism and appeals to ‘objective observation and systematic testing’, shunning (at least explicit) engagement with normative issues (Cohen 2007, 198). Consequently, problem-solving research on debt in China–Africa studies has usually not questioned (and in many cases explicitly subscribed to) the hegemonic narrative that Africa depends on external finance for its economic development, particularly to close the ‘infrastructure investment gap’. In line with Cox’s argument that the goal of problem-solving theory is to ‘provide guidance to correct dysfunctions or specific problems that arise within this existing order’ (1995, 31–32), this research has remained largely unconcerned with the wider political economy of sovereign debt in Africa.

On the other hand, there have been contributions that can be labelled ‘critical’ in Coxian terms, as they have shown analytical concern ‘with how the existing order came into being and what the possibilities are for change in that order’ (Cox 1995, 32). Drawing on various strands of historical-materialist and post-colonial theory, such ‘critical’ scholarship has interpreted Chinese (and non-Chinese) lending in Africa against broader transformations in the global political economy (see Carmody 2020; Goodfellow 2020; Tarrósy 2020; Carmody, Taylor, and Zajontz 2021; Zajontz and Taylor 2021). Epistemologically, such research emanates from a less orthodox IPE tradition that ‘evince[s] a deeper interest in normative issues’ and is ‘less wedded to scientific method and more ambitious in its agenda’ (Cohen 2007, 198). In the remainder of this article, I argue that the current conjuncture, marked by growing debt levels and renewed rounds of austerity and privatisation, demands an ambitious and critical research agenda that problematises the function of debt in late capitalism and calls into question dominant development paradigms and policies that have sustained Africa’s financial dependency.

Debt as a technology to extract African surplus

Much of the discussion around African debt owed to China has been largely preoccupied with providing an evidence-based discursive corrective to the ‘debt trap narrative’ – doubtlessly a commendable endeavour. However, we must not risk reducing debt to its discourse. Just like capital, debt is a social relation marked by asymmetrical material relations and power differentials between debtor and lender. As Di Muzio and Robbins argue in Debt as power,

debt within capitalist modernity is a social technology of power […]. In capitalism, the prevailing logic is the logic of differential accumulation, and given that debt instruments far outweigh equity instruments, we can safely claim that interest-bearing debt is the primary way in which economic inequality is generated as more money is redistributed to creditors. (2016, 7)

This brief intervention cannot provide a comprehensive history of how Africa has been subjected to debt peonage. Some pointers must suffice: besides the abuse of millions of Africans in a globalised slave trade and the systematic exploitation of African resources and labour, debt was another mechanism to extract surplus from colonial territories. For instance, debt incurred by colonial administrations for infrastructure was largely recouped through colonial taxation, commonly in kind and/or by means of corvée labour (Rodney 2015 [1972], 154; Muzio and Robbins 2016, 51–55; Zajontz 2021, forthcoming). Financial dependence of colonies on the metropole further increased after the Second World War. After independence, most African governments struggled to repay inherited debt, whilst simultaneously signing new loans, not least from the World Bank, for ‘modernist’ national development projects, including large-scale infrastructure. Often additionally compromised by mismanagement and corruption, post-independence, debt-financed development policies did little to address what Shivji (2009, 59) calls the ‘structural disarticulation’ of peripheral economies, a ‘disarticulation between the structure of production and the structure of consumption. What is produced is not consumed and what is consumed is not produced.’

Instead of creating room for autocentric development, excessive borrowing throughout the 1960s and 1970s exacerbated Africa’s dependence on the West. This was drastically aggravated by the second oil shock in 1979, when servicing dollar-denominated debt became increasingly costly. As Bracking and Harrison (2003, 6) argue, ‘[t]he majority of the newly independent states had been effectively delivered into twenty years of indentured labour. From that point access to finance became a key policing mechanism of African populations.’ In the name of macro-economic stability and fiscal discipline, public goods, assets and services were commodified, state functions and service provision trimmed and social cohesion further curtailed through SAPs. Crucially, ‘adjustment programmes have deepened the dependence of implementing countries not only on imports but also on international creditors’, with Africa’s debt figures rising throughout the 1990s despite draconic neoliberal reforms (Akokpari 2001, 41, 42). Between the early 1980s and the mid 2010s, developing countries transferred over US$4 trillion in interest payments alone to creditors in the global North (Roos 2019, 2).

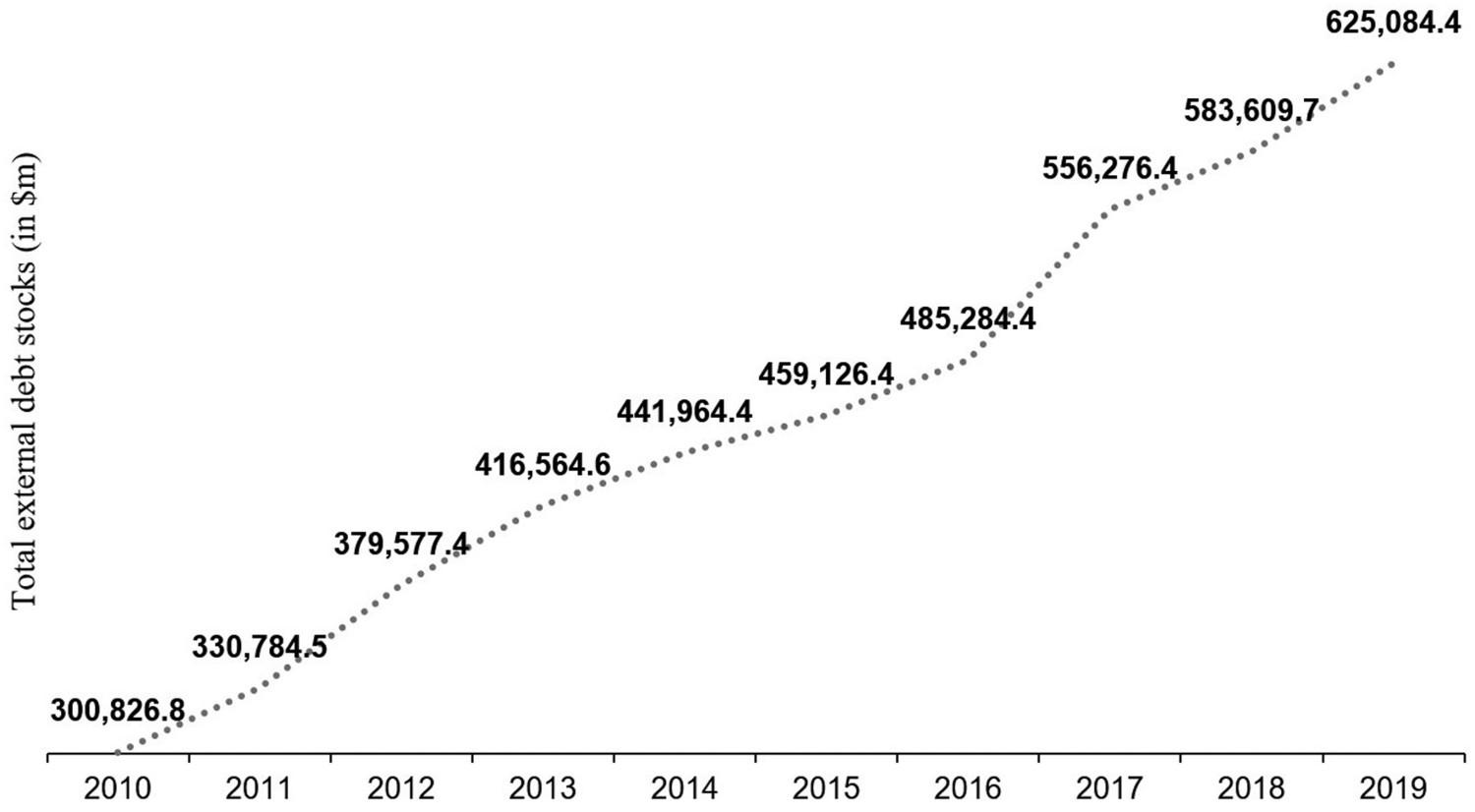

After highly indebted African states had seen significant debt write-offs under multilateral debt relief initiatives in the 2000s, it did not take long for the next debt cycle to commence. Riding on the growth wave of the commodities super cycle, African governments, now with relatively clean balance sheets, rushed onto global capital markets, and increasingly to Chinese policy banks, to sign bonds, loans and export credits, many of which related to ‘Africa’s re-enchantment with big infrastructure’ (Nugent 2018). Africa was said to be ‘rising’, and governments experimented again with debt-financed development policies. Over the 2010s, Sub-Saharan Africa’s external debt doubled (see Figure 1), whilst the region’s gross national income only grew by 15.8% between 2011 and 2019 (World Bank 2020).

The external debt of Sub-Saharan Africa (excluding high-income countries). Data source: World Bank (2020).

Africa’s most recent debt cycle has been characterised by a diversification of creditors and the rise of China to become the world’s largest capital exporter. With China having embraced capitalism, though with Chinese characteristics (see Taylor and Zajontz 2020), Chinese – just like Western – lending serves the accumulation of interest-bearing capital and, thus, the ‘expatriation of African surplus’ (Rodney 2015 [1972], 138) in the form of debt service. As Harvey (and before him Hilferding, Luxemburg, Bukharin, etc.) has shown, debt is essential for the survival of capitalism and integral to ‘spatio-temporal fixes’, i.e. the tendency of capital towards geographical expansion and temporal deferral (by means of debt financing) to counter overaccumulation crises (Harvey 2003, 115). As we have argued elsewhere, the increase in Chinese lending over the last two decades is a response to chronic overaccumulation within the Chinese economy (Taylor and Zajontz 2020; Zajontz 2020; Carmody, Taylor, and Zajontz 2021). Very much compatible with global calls to close Africa’s ‘infrastructure funding gap’, Chinese policy banks have been eager to finance all kinds of infrastructure (Goodfellow 2020; Zajontz and Taylor 2021).

States like Angola, Cameroon, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Republic of Congo and Zambia have since struggled to service their external debts, both Chinese and non-Chinese in origin (Bräutigam, Huang, and Acker 2020), whilst doubts about the economic viability of some Chinese-funded infrastructure projects have arisen (Tarrósy 2020; Taylor 2020). Indeed, Chinese lenders have, thus far and in light of the pandemic, been lenient by agreeing to reschedule debt and selectively and media-effectively forgiving matured, zero-interest debt (Kratz, Mingey, and D’Alelio 2020; Bräutigam 2020b). However, Africa cannot expect blanket debt forgiveness from Beijing, since China’s current spatio-temporal fixes rely on surplus creation that is temporally deferred in loan-debt investments. Although Chinese (state) capital is relatively ‘patient’ (see Kaplan 2021), it needs to see returns eventually. Otherwise, the ‘fix’ becomes increasingly fragile. Chinese lenders thus use a host of collateral arrangements, sovereign guarantees and confidentiality clauses to maximise chances of repayment (Gelpern et al. 2021). As ongoing negotiations about restructuring African debt show, Chinese and non-Chinese creditors jealously monitor whether debt relief granted by one lender is used by African governments to pay back another lender, with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) ensuring debtor compliance for the post-pandemic ‘payback period’.

Challenging the drivers behind Africa’s debt

Africa’s current debt cycle has been fuelled by ‘infrastructure-led development’, which is promoted by a ‘global growth coalition’ that advocates ‘financing and financializing infrastructure’ to get African ‘territories right’ for their seamless integration into global markets (Schindler and Miguel Kanai 2021, 45; see Zajontz and Taylor 2021). Since the 2000s, international financial institutions (IFIs), the African Union, donors, neoliberal consultancies, investment banks, powerful states (including China and the US), and African governments, have, in a mantra-like manner, reiterated Africa’s need for foreign finance to close the continent’s ‘infrastructure funding gap’. Goodfellow argues that ‘[f]inancial flows into Africa are being reoriented through the pervasive discourse of the “infrastructure gap”' (2020, 256), without much ‘questioning of who experiences it as a gap, by what standards it is determined and what influence it exerts on financial actors and policymakers’ (2020, 259). Much research in China–Africa studies has subscribed to this discourse and the paradigm of infrastructure-led development whereby Chinese (state) capital is considered a welcome ‘gap filler’. Yet unsustainable debt levels in several African countries demand critical analyses of hegemonic development paradigms and policies that have kept Africa dependent on foreign finance.

Undeniably, Africa requires regionally coordinated infrastructure development, including integrated networks of transport, energy and information technology, to transcend the mentioned ‘structural disarticulation’ of her economies. However, economic infrastructure does not automatically bring about structural transformation. It must be integrated with developmentalist policies aimed at (green) industrialisation, the protection of strategic productive sectors from extra-continental competition, and increasing public revenues. By and large, Africa’s recent debt-financed infrastructure boom has not been accompanied by such policies, as they are incompatible with neoliberal dogma. It is contradictory and cynical, yet at the same time systemic, that donors and IFIs, which yet again discipline unsustainable African debt, have, for decades, curtailed states’ capacities to raise capital internally. This was done by tying loans and grants to the creation of slim-regulation and low-taxation environments (supposedly a precondition for foreign direct investment) and to free trade policies, including external tariff cuts that damaged local industries. Chinese investors have since joined in the demands for tax holidays and free trade (Zajontz 2022, forthcoming), whilst prescribed liberalisations of capital markets have fostered capital flight from Africa (Hermes and Lensink 2015). Not least as a result of such policies, African public budgets have remained chronically underfunded, with new cycles of debt accumulation being a logical consequence.

As some African countries now face debt distress and renewed externally enforced austerity, further scholarship should critically assess the distribution of social and economic costs (and wins) that Africa’s external debts incur. Although sovereign debt service is often treated as a purely economic matter, it is highly political and marked by ‘distributional conflicts […] [that] feed into protracted power struggles between different social groups over who is to shoulder the burden of adjustment for the crisis’ (Roos 2019, 10). Long before the onset of the pandemic, unsustainable debt has caused non-payments of state employees as well as cuts in public service provision in Zambia (Zajontz 2020). In December 2020, the Kenyan government had to terminate tax reliefs aimed at cushioning the effects of the pandemic because of debt distress. Debt servicing costs have become the single largest budgetary item, surpassing the expenses for development projects and for the 47 counties by 86% between July 2020 and February 2021 (Munda 2021). The human costs of indebtedness are real.

Research should also be directed towards historically specific forms of ‘accumulation by dispossession’ (Harvey 2003, 137) that arise in the current debt cycle. Some scholars have embraced privatisation as a viable solution for debt-distressed African countries, with leading China–Africa experts advocating public–private partnerships (PPPs) and private equity investment in African infrastructure. Making reference to fiscal room created by the privatisation of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port or a Congolese highway, Bräutigam (2020b) argues that ‘we should be encouraging more of them. Equity investments are a smart way for countries to finance the operation of badly needed infrastructure, while also helping repay loans.’ Alden and Jiang (2019, 648) suggest that a shift from traditional loan financing to private equity investment ‘may help alleviate the dilemma posed by the combination of the need for infrastructure development and deepening debt difficulties’.

Such optimistic views conceal the fact that privatisation has been a ‘key facet of debt being mobilized as a technology of the powerful in our times’ (Muzio and Robbins 2016, 35). Hildyard (2016) demonstrates how PPPs in the global South have served as means for ‘financial extraction’ for foreign investors. This is not to say that PPPs are an ‘evil’ instrument per se. A lot depends on the capacity of African governments to negotiate beneficial terms. The protracted negotiations between a Chinese consortium and the shareholding governments of the Tanzania–Zambia Railway Authority (TAZARA) have, for instance, shown a great degree of strategic learning amongst African governments in negotiating PPPs (Zajontz 2022, forthcoming). Nonetheless, the agency and strategic scope of African state actors are constrained by mounting debt and its inherently asymmetrical structure.

Towards ‘a united front against debt’2?

Staden, Alden, and Wu (2020, 119) suggest that one way of countering power imbalances vis-à-vis external powers could be ‘agency through compliance/non-compliance’ whereby ‘Africans [are] strategically not fulfilling the terms of agreements to which they ostensibly assented.’ In 1987, Sankara tried to organise such agency through non-compliance:

Debt cannot be repaid, first because if we don’t repay, lenders will not die. That is for sure. But if we repay, we are going to die. That is also for sure. Those who led us to indebtedness gambled as if in a casino. As long as they had gains, there was no debate. But now that they suffer losses, they demand repayment. And we talk about crisis. […] We cannot repay because we don’t have any means to do so. (Sankara 2019 [1987])

As Roos documents in Why not default?, whilst very common in earlier times, sovereign defaults have become much less frequent since the 1980s due to ‘three enforcement mechanisms of debtor compliance’. First, highly indebted countries face the structural power of an ‘international creditors’ cartel’ that enforces market discipline by withholding further credit and/or attesting to countries’ credit unworthiness, thereby making further borrowing prohibitively expensive (Roos 2019, 11). Zambia felt this structural power when deteriorating ratings by the ‘big three’ agencies made it increasingly difficult for Lusaka to stay liquid, and investors in a maturing Eurobond rejected rescheduling. Also, the China Exim Bank declined further funding for Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway, a project that depends for its feasibility on a rail link to Uganda (Carmody, Taylor, and Zajontz 2021).

Second, international lenders of last resort employ conditional loans and ‘rescue packages’, which ‘keep the debtor solvent while simultaneously freeing up resources for foreign debt servicing’ (Roos 2019, 11). The IMF is yet again involved in ‘debt diplomacy’ in several African capitals – this time mediating divergent interests of a much more diverse set of creditors (Chinese and non-Chinese, public and private, bilateral and multilateral). Third, ‘fiscally orthodox elites’ play a crucial ‘bridging role’ by complying with austerity requests in order to recover creditworthiness, often at the price of societal needs (Roos 2019, 11). Vera Daves, finance minister of Angola, the African country that has signed the most loans from China and whose debt-to-GDP (gross domestic product) ratio surpassed 130% by the end of 2020, outlined her government’s priorities amidst the pandemic: ‘Our priority is to survive, save as many lives as possible, and prevent the healthcare system from collapsing. Then we want to reach a bearable debt level’ (quoted in Pelz 2020; emphasis added). Austerity – prescribed by the IMF and lenders but implemented by African officials – will be the renewed order of the day.

Reminiscent of George Ayittey’s call for ‘African solutions to African problems’, Ghana’s finance minister Ken Ofori-Atta recently called for debt relief from China and wrote in the Financial Times that Africa’s renewed debt crunch demanded

a tectonic shift of the global financial architecture. That requires ambitious reforms to address fundamental inequities in the global financial system. […] African nations cannot wait for others to act. We must take the lead by establishing a secretariat to co-ordinate the varied interest groups and centres of power to propose a restructuring of the global financial architecture. […] Africa is not asking for charity. It is asking for equity. (2020)