Introduction

Fighting has long been used to settle disagreements. Advancement across civilisations and multilateral efforts to end conflict such as adherence to the Westphalian Principle and the creation of the United Nations have largely failed to end wars (Al-Khasimi 2016). Technological developments beginning with the industrial revolution as well as advances in the development of weapons of warfare have contributed to the increased intensity, prevalence and duration of conflict (Kissinger 2014, 331). The development and mass adoption of information and communications technologies (ICT), especially social media, have further helped to boost and spread a new brand of conflict perpetrated by non-state actors and which is mostly based on religious ideology (Nye 2011). The world is currently in the throes of raging insurgencies fuelled by a combination of imperialism, climate change, religious extremism and social media.

The Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria has found a base in the North East region. This terrorist network has shown resilience despite efforts of the Nigerian government to defeat it (Thurston 2016). Depressingly, it has become a transnational problem which has so far defied the military interventions of governments of countries in the Savannah and Sahel regions of Africa. Chad, Niger, Cameroon and Nigeria have combined resources as well as strategy but have been unable to seriously damage, let alone defeat, the terrorist group (Mahmood and Ani 2018).

The attacks of the terrorists have led to a huge number of internally displaced persons (IDPs), people who have abandoned their homes in remote places that fall under the terrorists’ rule and fled to the safety of areas under the total control of government forces. According to the UN Refugee Agency UNHCR (2020), the Boko Haram insurgency has displaced about 2.7 million persons in the north-eastern part of the country. At the height of its power, Boko Haram was in control of 17 local governments across the North East states of Borno, Yobe and Adamawa (Human Rights Watch 2016). The intense fighting, which results from attacks and counterattacks between the government forces and the insurgents, has stunted development in these constituencies.

About 40,000 people have been killed, including insurgents, members of security forces and civilians, especially in these states, while many more have been kidnapped for ransom or forcefully recruited (Campbell and Harwood 2018). Business activities have taken severe hits while elections and elected political leaders have largely abandoned their constituencies. According to the World Bank (2019, 15), about US$9.2 billion in infrastructure damage and US$8.3 billion in output losses have been recorded in the region from the bombings, raids and razing of communities. Questions arise: what is the fate of these constituents who have been displaced by the conflict? To what extent have they been politically represented, given the ongoing conflict? Have elections been conducted in these constituencies? Do elected representatives from these constituencies engage in consultations with displaced persons?

This briefing will examine the conduct of elections in areas affected by the Boko Haram insurgency and appraise the political representation of these constituencies through the lens of constituency consultation. This paper is the first to analyse the conduct of elections, constituency consultation and political representation in a conflict environment as regards the Boko Haram insurgency. It unravels the links among conflict, consultation, conduct of election and political representation in the areas witnessing intense terrorist activities. The rest of the paper is organised as follows: the first section delves into the Boko Haram insurgency. This is followed by discussions on the concept of political representation and importance of constituency delimitation. The next section highlights the conduct of elections and constituency consultations and estimates how they are affected by terrorist activities. The briefing concludes with suggestions on improving political participation and representation in conflict zones.

Rise of Boko Haram

In 2009, Nigerians were shocked by the news of the conflict in Maiduguri, a cosmopolitan city on the north-eastern edge of Nigeria. Security forces battled with an Islamist extremist group, Boko Haram, for days. The scale of casualties of the conflict was the real shock. Over 700 of the insurgents were killed in combat (Campbell and Harwood 2018). The leader of the group, Mohammed Yusuf, was captured but died in police custody, and the group went underground (Smith and Associated Press 2009). This marked the birth of Islamic terrorism in contemporary Nigeria.

The Boko Haram insurgency since then has become intractable and attained international notoriety. The group announced itself on the global stage when it bombed the United Nations building in Abuja, killing both local and international staff (Campbell 2011). This drew swift global condemnation. The insurgents also targeted police and military formations and other soft targets including houses of worship, schools and markets. The terrorists made gains while government security forces retreated, succumbing sometimes to the superior firepower of the insurgents whom the military seemed to have underestimated (Adibe 2016). The military gave excuses for its inability to deal with the escalating threat of the terrorists. The performance of the political leaders was no better. They peddled conspiracy theories about the origin and intentions of the insurgents, blaming a cabal of northern elites who were bent on truncating the President Jonathan administration (Adibe 2016). A low point was the kidnapping of over 270 girls (the exact number remains unknown) from a school in Chibok, a remote part of Borno state (Blanchard and Husted 2019). The girls, who were preparing to write final secondary school exams, were abducted by the terrorists who made demands before their release, and many remain in captivity (The Telegraph 2016). The administrator of the government at the time disputed the claims of the kidnapping while blaming the media and foreign interlopers who were trying to discredit his government as the elections were approaching.

In late 2010, as the April 2011 general elections approached, the insurgents stepped up their attacks, targeting churches, mosques and schools. The terrorists were determined to halt the elections, with the aim of forming a caliphate in the North East. They also continued their attacks after the elections, targeting military/police formations including police headquarters and an elite military training school in Kaduna state.

Local politics and origin of Boko Haram

The insurgents, some argue, metamorphosed from a collection of religious extremists into full-fledged terrorists due to mishandling of local grievances by the Borno state government (Aziken 2016). For example, it is alleged that the group was provoked by the security forces after about 17 of their members were killed while taking part in a funeral procession in 2009. The complacency of the government, which failed to condemn the killings, apologise or conduct an inquiry, is said to be what fuelled the anger of the sect. It also alleged that Senator Alli Modo Sheriff once used the services of the sect between 2003 and 2004 to unseat a former governor, Mala Kachalla, on whose Sharia implantation council, Mohammed Yusuf, the leader of the Boko Haram sect, once served but from which he had resigned in disgust because he felt its recommendations were not sufficiently far reaching (Perouse de Montclos 2014; Thurston 2016). In a bid to achieve his aim, Sheriff was believed to have armed a group of political thugs in Maiduguri. This group gained the local nickname of Ecomog (not to be confused with the eponymous ECOWAS Monitoring Group), and, with Yusuf, followed Sheriff’s instructions, for example intimidating political opponents. After becoming governor, Sheriff, according to proponents of this camp, reneged on his promises to the group (such as implementing strict Sharia law in the state, a move already embraced warmly by many northern states) which made Yusuf accuse the Sheriff government of corruption. In response to these accusations, Yusuf's disciple Foji Foi was made a commissioner of religious affairs, and Sheriff later resigned (Ajakaye 2014, Thurston 2016).

A day after the killing of 17 of his members, the leader of the sect, Yusuf, granted an interview in which he threatened to retaliate while promising a Jihad. The governor of the state at the time, Senator Sheriff – against the wise counsel of a former attorney general of Borno state – ignored the sect (Aziken 2016), who then carried out their threat of retaliation, feeling they had been betrayed. Since then, the North East has known no peace.

The concept of political representation

The doctrine of accountable government derives from the assumption that elected representatives are responsible to the people they govern and must put the interests of the people above their personal interests, and this could arise out of a sense of moral responsibility as elected representatives feel duty bound to be responsible to their constituents (Fukuyama 2014). The contemporary debate on political representation is shaped by the work of Pitkin (1967) and Mansbridge (2003, 2009), who identified four distinct forms: formalistic, symbolic, descriptive and substantive political representation. What these forms of representation have in common is that the representative draws their legitimacy from a formal procedure through which they are selected, such as by an election. Elections, therefore, serve as a whip used by the electorate to compel accountability. Pitkin emphasises that these forms of political representation must be understood within the context in which they are being exercised.

Pitkin’s (1967) formalistic and substantive concepts of representation are apt for the objectives of this paper. In formalistic representation, the representative gains authorisation to represent constituents through a formal process such as elections. The representative is therefore an agent acting on behalf of the constituency he represents. Although there is no formal method of evaluating how well a representative performs, there is a formal process of accountability that constituents can use to reward or punish the perceived performance of the representative. A representative who performs well in the eyes of the constituents may be rewarded with re-election while a bad performer will be punished through either elections or a recall process. Under substantive representation, the representative is expected to advance the interest of the constituents he represents at all times and his representative performance is assessed based on what he has been able to achieve for his constituency.

Importance of constituency delimitation

The Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), Nigeria’s electoral umpire, is mandated to carry out delimitation of constituencies at intervals of not less than 10 years. According to Ozoh (2012, 22), one of the reasons for delimitation is to look after ‘population dynamics and geographical considerations to ensure effective and efficient representation of constituents and for the ease of conduct of elections’. This exercise is mandated by the constitution under section 73 as amended. In Nigeria the last delimitation exercise was conducted in 1996 and it was based on the 1991 census (Ozoh 2012). The laws enabling constituencies’ delimitation made provision for 109 senate seats, 360 Federal House of Representative seats and no constituency overlaps across multiple states, but the national assembly approves new constituencies that arise out of a delimitation exercise.

However, there are several challenges that affect delimitation exercises in Nigeria. Population size, geographical contiguity, historical, cultural and ethnical affinity, and physical and natural features are normal metrics used in guiding delimitation as mandated by the constitution. Getting this mix right is a tall order. Nevertheless, there are globally accepted guiding principles that should be employed, including impartiality of the authority conducting the exercise, equality of constituents, representativeness, non-discrimination, transparency and openness, legitimacy and inclusivity (Handley 2007). Overlapping of these principles, due to challenges, could create a problem with unacceptability. Indeed, the lack of legitimacy of most electoral contests derives from poor delimitation processes, which tends to accentuate mutual suspicion and ethnic rivalry. Poor delimitation leads to ineffective representation, as elected representatives who are seen as illegitimate feel no pressure to be accountable to electorates who consider them illegitimate.

Election and constituency consultations in Boko Haram strongholds

The Boko Haram insurgency has affected mainly three states – Borno, Yobe and Adamawa. Borno is the most affected and it is where the terrorist organisation started. Yobe, which is adjacent to Borno, has also witnessed intense fighting, while Adamawa, which is to the south of Borno and which borders Cameroon, has seen intense fighting too.

These states, along with others in the North East and beyond, host displaced persons in camps. Several IDP camps dot these states, and some camps have come under attack by terrorists (Mbiyozo 2017). The government struggles to protect and provide the necessary humanitarian assistance to displaced persons even with the assistance of numerous humanitarian organisations that have occupied the North East. For more than a decade since the insurgency started, no local government elections have been conducted in Borno state. In fact, the first local government elections were conducted in November 2020, 13 years after the previous elections, in which about 5000 IDPs voted. The local governments were managed by appointed caretaker committees. Boko Haram has always threatened to attack electorates and polling centres if elections were conducted (Bloomberg 2015). However, federally conducted elections have been held in these states including in IDP camps.1 Prior to the 2019 general elections, the INEC released its regulations for voting by IDPs. The opposition parties impugned the credibility of the exercise, describing the IDPs as vote-rigging centres.

A key challenge for political representation in these areas is that people from different constituencies have been bundled into these camps. Many of these camps are far from the constituencies that were originally home to many of the displaced persons, and due to the prevailing security situation they have all been kept in camps in safe areas. This situation therefore raises many questions: who represents these camps? Is it the representatives in whose constituencies these camps are located? What happens to the representatives whose constituencies have been sacked, and hence cannot hold consultations? What happens to the constituency projects that have been budgeted for but cannot be carried out, due to the security situation?

The IDP camps, it will be assumed, are a good place for consultation since the displaced persons are all located in one place. The question is, then, who represents these ‘displaced constituents’? Should the representatives from conflict-affected constituencies co-represent constituents in displaced camps? In this case, there would be multiple and overlapping representatives. Worse for representation for these conflict-affected areas is the fact that many of the elected representatives from these areas have stayed away from their constituents due to insecurity. For example, some federal lawmakers have not visited their constituency for years for fear of being killed or kidnapped by Boko Haram.

Estimating the impact of Boko Haram insurgency on elections, constituency consultation and representation in affected states

Given the lack of data on constituency consultations, especially in Borno, Yobe and Adamawa states, this paper uses Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) to determine elected representatives’ ability to meet with their constituents. ACLED is a crisis mapping project that provides information on current conflict and disorder patterns. We compare the ACLED data with representation in a region that is not witnessing ongoing wide-scale conflict, for example in South West region.

Although other regions such as South East and South-South are not enduring as much conflict as the North East, activities by the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) group have startled politicians who have been branded as traitors for exercising their freedom in these areas, while in South-South region, the legacy of militancy and widespread kidnapping is assumed to affect constituency consultation. IPOB is making secessionist demands and has engaged in kidnappings, assassinations and jail breaks.

The North West region is enduring industrial-scale armed banditry, while the North Central region is in the throes of frequent kidnappings, recurring communal clashes and herdsmen/farmer clashes. It is assumed that elected representatives will stay away from constituencies experiencing intense Boko Haram attacks or with a high probability of being attacked. Attacks on elected representatives or political institutions such as local government secretariats, police posts and military units heighten anxiety among elected representatives, who as a result stay away from their constituencies.

Also, we assume that elected representatives in non-conflict areas visit their constituencies and spend significant time with their constituents (Mezey 2011) during the annual recess and end-of-year recesses as well as during religious holidays, which provide opportunities for them to interact with their constituents.2

In the 10 years up to the end of 2019, the Boko Haram insurgency claimed over 40,000 lives, although the intensity of the insurgency reached its peak when the terrorists occupied several local governments in Borno, Yobe and Adamawa states. Since then, there has been a reversal of the gains made by the terrorists, although they still engage in deadly attacks in which they temporarily sack villages and at times entire local governments before being pushed out of the occupied territory by the armed forces.

ACLED data show that security deteriorated significantly between 2014 and 2015, towards the end of the electoral cycle. As the 2015 elections approached, and with many apprehensive over the ability of the government to conduct peaceful, free and fair elections, Boko Haram, in a bid to discredit the election, intensified attacks, which made 2015 the worst year in terms of fatalities.

Constituency consultation

Table 1, along with our assumptions, shows that in the five years between 2015 and 2019 there were a total of 57 weeks of recess that representatives could have used to engage in consultations with their constituents. The annual recess, which is longer, amounts to 37 weeks in the five years under review, while the Christmas break periods came to 20 weeks in total.

Federal parliamentary recesses between 2015 and 2019.

| Year | Annual recess (weeks) | End of year recess (weeks) | Total recess (annual and end of year in weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| 2018 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| 2017 | 8 | 3 | 11 |

| 2016 | 8 | 4 | 12 |

| 2015 | 9 | 3 | 12 |

| Total | 37 | 20 | 57 |

Source: Authors’ calculations from National Assembly data.

In a region not witnessing large-scale armed conflict, elected representatives are expected to spend a ‘significant’ part of the 57 weeks engaging in meaningful discourse with their constituents, if our assumptions hold. Thus, in a region like South West, an elected representative will most certainly spend a significant part of their recess in their constituencies engaging in town hall meetings and receiving interest groups and individual guests at their constituency offices and country homes.

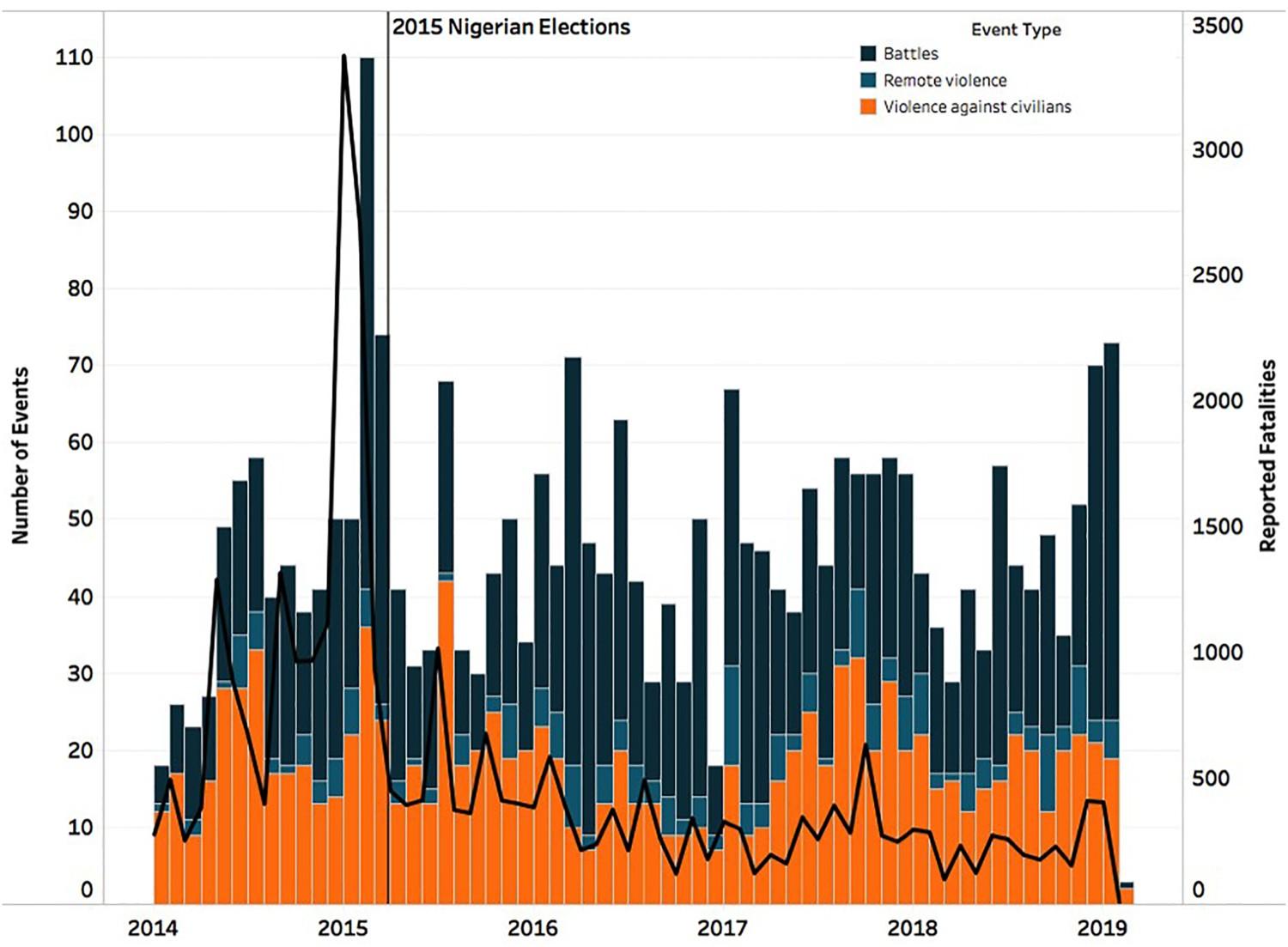

Figure 1 sets out a record of the numbers and types of events – battles, remote violence and violence against citizens – that took place between 2014 and the end of February 2019. In Boko Haram-affected states, the terrorist group carried out 2800 attacks over this period, resulting in over 31,000 fatalities, making Boko Haram one of the world’s deadliest armed groups (ACLED 2019). Indeed, reports have indicated that palaces of traditional rulers (district heads), police posts, military outposts and homes of prominent politicians have been attacked in the past by Boko Haram. The convoys of incumbent governors have also been attacked in the past by the insurgents (TheCable 2019). This level of attacks means that politicians cannot visit their hometowns or constituencies to hold consultations. This is also confirmed by the many constituency projects that have not been carried out, which contractors and representatives have blamed on insecurity (Elumoye and Olugbode 2019). However, the question is: what level of consultation took place between the representative and their constituents before such projects were agreed on? Given that Boko Haram was at its peak, as it occupied several local governments in Borno, it is safe to assume that consultation did not take place, thereby weakening effective representation.

Violent events and reported fatalities associated with Boko Haram, by type of event (1 January 2014–2 February 2019).

Source: ACLED (2019).

Elections

With the frequency of attacks, especially close to elections, and with thousands of people dead, it is clear that holding elections in an atmosphere of instability will be fraught with challenges. Indeed, elections had to be postponed by six weeks in 2015 due to the deteriorating security situation in the North East, which added further tension to the fragile political situation. Many feared that the delay was an attempt to interfere in the coming presidential election using the cover of deteriorating security situation in the North East as a result of Boko Haram activities (Blanchard 2015).

Voting in a conflict zone comes with challenges of legitimacy and to the credibility of the electoral process. In February 2015, there were an estimated 1.2 million IDPs in this region and parts of the North Central region. The INEC was only able to conduct elections in IDP camps in Borno, Adamawa and Yobe states, and only areas under government control were mobilised to vote (Rushing 2015). Voting by IDPs in Borno state took place in designated camps, and this policy excluded other displaced persons who were living not in camps but with compassionate families that took them in. Many lost their voter’s card when fleeing from Boko Haram attacks and thus were not allowed to vote in IDP camps. Those who fled due to rising insecurity and fear of imminent attacks were ignored by the INEC, while those who fled direct attacks and were dwelling in camps were allowed to vote. This discrimination by the electoral umpire disenfranchised a large number of people who were qualified to vote but were excluded because they did not reside in IDP camps. Many had thought that, given the prevailing security situation in the affected states, the INEC would make allowances for those who had their voter’s card and their name in the voter’s register, but they were ignored.

Weeks before the election, the INEC released guidelines for election procedures in IDP camps in December 2019. Although the framework on voting in IDPs was created for 15 states, the focus was mostly on the Boko Haram-affected states. According to the guidelines, intra-state IDPs would participate in all election categories when and where applicable, while inter-state IDPs would participate in presidential elections, in order to dispel suspicion over transmission of results across state borders and constituency boundaries (Commonwealth 2019). According to estimates, over 400,000 IDPs living in camps in Borno state were expected to vote in the 2019 general elections in 10 special voting centres. Figure 2 highlights the number of persons displaced in 2018 due to conflict and violence, which shows the burden of conducting elections for IDPs in conflict areas.

New displacements, 2018 (conflict and violence).

Source: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC 2019, 6, Figure 5).

Representation

The question is whether there can there be meaningful representation in the absence of consultation. Given the large number of IDPs in Boko Haram-affected states, it is important to understand how well they are being represented. According to Cordenillo and Gardes,

political representation goes beyond the act of voting in elections; they also embody the freedom of citizens to express their opinions and to mobilise to influence policy. Without citizens’ participation, and the rights, freedom and means to participate, the principle of popular control over government cannot begin to be realised. Without representation, public institutions that are socially representative of citizens cannot be developed. (Cordenillo and Gardes 2014, 5)

Conclusion

In the last 10 years the Boko Haram insurgency has affected all facets of life in the studied region. Thousands of lives have been lost, property has been destroyed and many people displaced. This paper has shone a spotlight on the activities of the terrorists as regards the disruption of the normal workings of participatory democracy. Thousands of displaced persons have been disenfranchised of their vote, while representatives have not been able to conduct consultations and render effective representation.

From our calculation, several weeks that could have been used by representatives to engage in consultation with constituents have been lost. What can be done? In the absence of properly identified constituencies, in the case of IDP camps, the political authorities should design legislation to make a special case for representation of IDPs with constituents from diverse constituencies. Such legislation should make the case for overlapping representation, whereby representatives can co-represent constituents from overlapping jurisdictions. This will allow for proper consultation, in the sense that constituents can easily know who represents them. Although nothing in the law says that this cannot be done, it is important for things to be institutionalised so that no representative can shirk their responsibility and feign ignorance of who their true constituents are and where they may be located. It is important for people to have effective representation, as the absence of it can delegitimise the democratic process and hence reinforce grievances such as those that gave rise to the Boko Haram insurgency in the first place. An engaged representative helps to improve the perception of democracy in the minds of the constituents. In contested elections, accountability – as reflected in effective consultation and representation – reinforces participatory democracy by giving voice to constituents in policymaking through their representatives.