Introduction

Following amendments to the Electronic and Postal Communications Act, Cap. 306 of 2021 (Government of Tanzania 2021), the government of Tanzania introduced a levy on airtime which came into operation in July 2021. ‘Airtime’ was not defined in the regulation, but the levy is explained as being applicable to the purchase of mobile phone data by subscribers and is applied at the point of purchase of the data voucher. It was called a ‘solidarity tax’ by the finance minister and came into effect on 15 July 2021. This has increased the costs of mobile transactions by raising a levy on mobile money transactions. The term solidarity tax was used because the Tanzanian government planned to use the revenue collected for the construction of unfinished government projects and improvements to social services, hospitals, roads and the construction of about 300 classrooms.

A ‘solidarity tax’ is not an unknown phenomenon, and has been deployed by several countries at various times. Portugal, South Korea, Chile, Austria and France have at different times introduced a solidarity tax to reduce inequality, while Czechoslovakia introduced such a tax to finance recovery from the effects of World War I. Germany introduced a similar tax in 1991 to provide capital for the costs of reunification. In Africa, countries have introduced or reintroduced solidarity taxes to regulate the impact of Covid-19. Nigeria and Kenya did this in 2020, but in the latter case there was an outcry because of the misappropriation of the revenues, and the taxes were seen to be overextended and oppressive (Waris 2021).

According to the United Nations (n.d.), about 42% of the population in Sub-Saharan Africa are living below the poverty line. The Covid-19 pandemic made the situation worse by pushing about 70 million people back into poverty. This is an emergency, and strategies to redress it should not disproportionally affect the poor. Taxing mobile phone airtime and financial transactions increases the costs of the financial services used by the poor. Mobile money has increased financial inclusion and financial deepening and thus economists such as Ndulu (2019), a former governor of the Central Bank of Tanzania, favoured a focus on infrastructure and friendly tax regimes when he advised Uganda, in order to increase the usage of mobile financial services and fight poverty. This advice is applicable to Tanzania as well, because they are both developing countries with low levels of financial inclusion.

Levies on airtime and mobile transactions may undermine the gains from mobile financial services: increasing financial inclusion and reducing poverty (Adam and Ndulu 2016; Donovan 2012). Introducing taxes on mobile financial services is likely to reduce financial inclusion, inhibit the increase in the stock of financial assets or financial deepening, a term used by economists to describe the ability of financial institutions to mobilise financial resources for development (Nzotta and Okereke 2009). Limiting that ability increases poverty, on top of the Covid-19 effects on the economy that have pushed more people into extreme poverty.

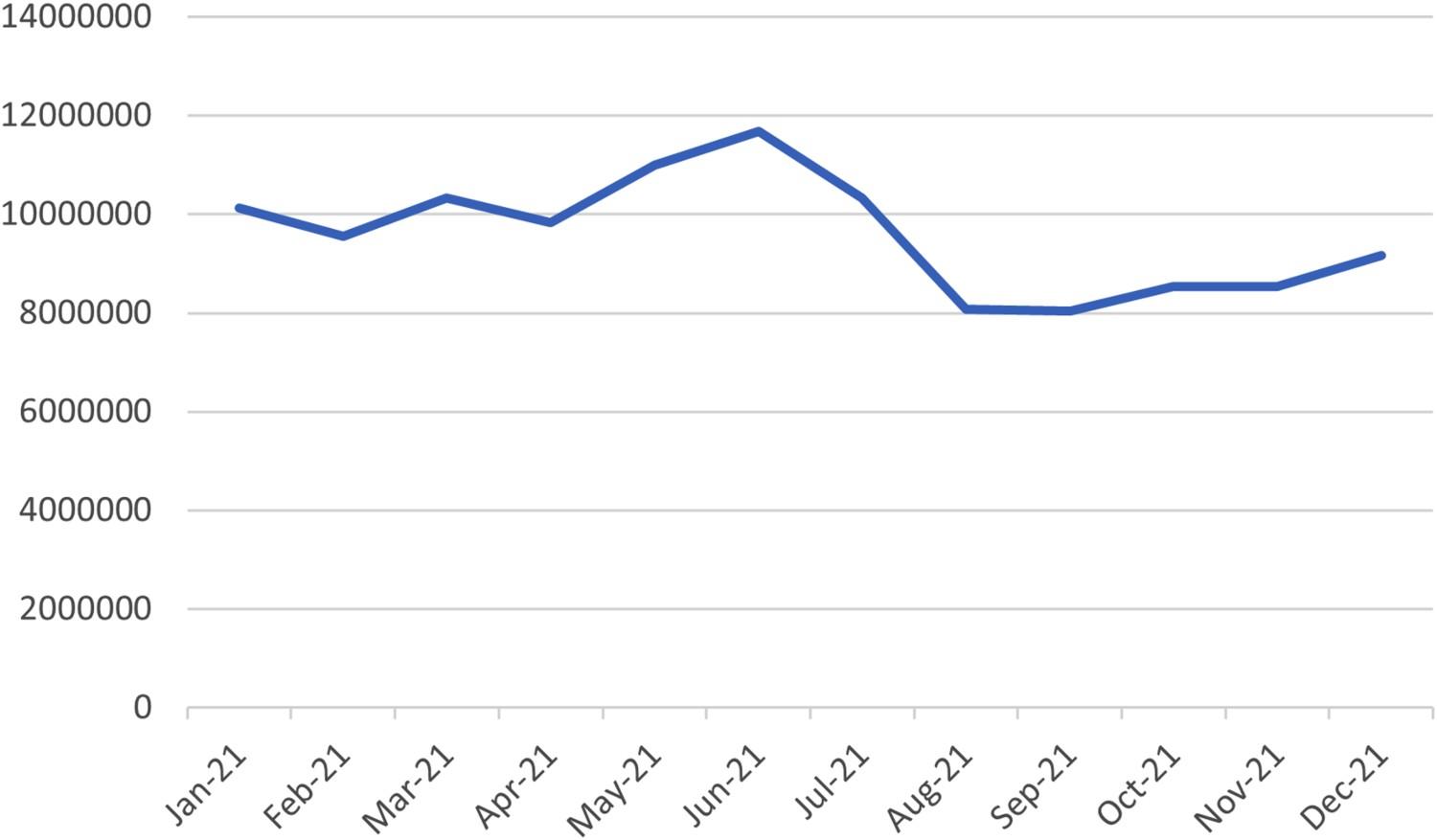

The solidarity tax is separate from other charges that the government levies on telecommunication services. The revenue that government gets from mobile money fell after the introduction of the solidarity tax. The Global System for Mobile Communications Association (GSMA), in its 2021 impact analysis report on Tanzania’s mobile money levy, found a decline in total revenue from mobile money immediately after the introduction of the solidarity levy, proving that financial inclusion has been affected (GSMA 2021). Financial and insurance activities contribute 3% to Tanzania’s gross domestic product (GDP), which means that any negative disturbance to it affects financial inclusion. Figure 1 shows that the revenue from mobile money increases after the adjustments made in August after complaints were made, but this is unfair, because consumers have fewer options when it comes to the means of sending and receiving money conveniently.

Reasons given for the new tax

President Samia Suluhu and the minister of finance explained in July 2021 that the solidarity levies are intended to help fund improvements for social services. On 19 July, Ummy Mwalimu, then minister of state in the President’s Office – Regional Authorities and Local Government, said that the revenue from the levy will be used to construct 10,000 classrooms, 4500 dispensaries and 570 health centres. Elsewhere such a tax has been introduced as a result of a crisis event, such as sudden population growth or an unexpected economic crisis, but in this case there was no such event. The enrolment of students is predictable, so remarking on the lack of classrooms suggests a lack of planning rather than a sudden emergency. The effects of Covid-19 have impacted on tourism, and prices of agricultural inputs have risen in Tanzania. But the inadequacy of classrooms has not been caused by Covid-19. In any case, Tanzania received a loan of US$567.25 million from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 2021 to help mitigate the emergency costs of health and the impact of the pandemic (IMF 2021).

Alternatives to the solidarity tax

Raising revenue on existing taxes

The tax-to-GDP ratio is a gauge that measures tax revenue relative to the size of the economy as measured by GDP. It provides one mechanism that influences the direction of tax policy (Kagan 2021). When the tax-to-GDP ratio is higher, this may indicate more effective government collection of revenue. The IMF has recommended that developing countries should have a tax-to-GDP ratio of at least 15%, which is assumed to be enough for a country to finance its basic activities. Tanzanian’s tax-to-GDP ratio is 14%, which means that Tanzania collects less revenue relative to the size of its economy. This calls not for another tax base to be established, but rather for improvement of the existing tax bases in order to increase the revenue collected. A study commissioned by ActionAid Tanzania (2021) showed losses of US$7.8 billion a year as a result of the failure to collect tax revenue from the informal economy, inefficiencies at the local government level, failure of public authorities to issue electronic receipts, inadequate tax compliance, non-payments of tax arrears, unresolved tax appeals, unresolved tax objections, harmful tax incentives and illicit financial flows. The study recommended reviewing tax treaties, stopping harmful incentives, addressing non-compliance and non-payment and improving revenue generation at the local government level. If the recommendations of studies on tax collection had all been implemented, the study considered it likely that the tax-to-GDP ratio would have risen to 28.5% (ActionAid 2021).

Polus and Tycholiz (2019) showed that oil and gas corporations regularly avoid meeting their tax obligations. This is, among other things, because of the asymmetric information and power relations between the government and the corporations. In their article, the authors observed that in 2017 the profit of three larger oil and gas corporations in Tanzania was three times greater than the country’s GDP of 2017/18 (Polus and Tycholiz 2019).

Financial inclusion

Financial services are essential in eradicating poverty. One definition of poverty is a lack of access by poor people to the instruments and means that they need to improve their lives. It is not just a lack of money (Donovan 2012). Mobile financial services have increased financial inclusion and reduced poverty (Adam and Ndulu 2016; Donovan 2012). Mobile financial services are increasing in Tanzania. The majority of people who could not access the commercial banks which dominate the financial system benefit from financial services for saving money, issuing loans and insurance that are offered by mobile money services. Mobile money has increased a trend towards a cashless society as the number of people who are using mobile money do so to pay for goods and services. The increasing number of people who have subscribed to mobile money services has made innovative mechanisms for payments – such as scanning QR codes to make government payments and other services – more popular, and thus the transactions have increased in tandem with the increase in active users. As detailed in Table 1, in January 2013 the number of mobile money subscribers was 27.4 million with 8.1 million of these as total active users; the number increased to 108.7 million and 33.1 million respectively in December 2021. The total value number of mobile payments also increased from TSh1.97 trillion in 2013 to TSh9.2 trillion in December 2021.

Numbers of mobile money subscribers and active mobile money users in 2013 and 2021.

| Mobile money subscribers | Active mobile money users | |

|---|---|---|

| January 2013 | 27,430,274 | 8,078,452 |

| December 2013 | 31,830,289 | 11,016,757 |

| January 2021 | 109,148,106 | 30,987,198 |

| December 2021 | 108,681,990 | 33,142,118 |

Source: Bank of Tanzania n.d.

Financial inclusion increased after the introduction of the mobile money services but had to be incentivised with an environment to increase the number of people with financial access. The cost of sending and receiving money was one of the incentives, but the solidarity tax then increased the costs of sending and receiving money. These costs thus reduced usage: Vodacom in Tanzania in February 2022 noted that financial transactions have decreased by 24.8% since the implementation of the solidarity tax. The reported decline was in the last quarter of 2021 (Jamii Forums 2022).

The solidarity tax is specific to mobile money users and thus GSMA (2021) recommended that, to ensure fair competition, the tax should be charged on all financial services including over-the-counter cash transactions.

The tax on mobile transactions and airtime has increased the costs of transactions, and it is charged on top of the value-added tax (VAT) at 18% that government takes. Table 2 shows the fee (VAT inclusive), and the government levy that is charged now. If you take the fee plus the government levy, you get the amount that the mobile money customer pays in transactions. I have taken Vodacom fees as an example because it is the leading telecommunications company in Tanzania. While there are six companies that offer mobile money services, M-Pesa (Vodacom’s mobile money service) has 40% of the market share of mobile money (TCRA 2021). Taking the VAT and the levies on mobile transactions, it becomes clear that the government takes more than the network companies get in transactions, especially from transactions over the threshold of TSh20,000, where the percentage of government levy to total cost of the transaction is greater than 50%.

The costs of mobile transactions (in TSh).

| For sums in the range of | Fee to send sum to Vodacom | Fee to send sum to other networks | Fee to withdraw sum | Fee to send sum to bank | Government levy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200–499 | 15 | 15 | 80 | 100 | 0 |

| 500–999 | 15 | 15 | 175 | 100 | 0 |

| 1000–1999 | 30 | 35 | 350 | 200 | 10 |

| 2000–2999 | 30 | 45 | 400 | 200 | 11 |

| 3000–3999 | 50 | 68 | 600 | 200 | 19 |

| 4000–4999 | 60 | 81 | 650 | 400 | 39 |

| 5000–6999 | 130 | 180 | 950 | 800 | 70 |

| 7000–9999 | 150 | 180 | 1000 | 800 | 88 |

| 10,000–14,999 | 350 | 495 | 1450 | 1200 | 224 |

| 15,000–19,999 | 360 | 495 | 1450 | 1200 | 427 |

| 20,000–29,999 | 380 | 540 | 1850 | 1800 | 672 |

| 30,000–39,999 | 400 | 612 | 1850 | 2400 | 770 |

| 40,000–49,999 | 410 | 675 | 2350 | 2400 | 1050 |

| 50,000–99,999 | 720 | 1125 | 2700 | 2800 | 1435 |

| 100,000–99,999 | 1000 | 1440 | 3650 | 3600 | 1771 |

| 200,000–299,999 | 1200 | 1710 | 5300 | 5000 | 2058 |

| 300,000–399,999 | 1500 | 2070 | 6500 | 6000 | 2450 |

| 400,000–499,999 | 1500 | 2250 | 7000 | 6000 | 2870 |

| 500,000–599,999 | 2200 | 2880 | 7500 | 8000 | 3640 |

| 600,000–699,999 | 3300 | 3870 | 8000 | 8000 | 4480 |

| 700,000–799,999 | 3300 | 3870 | 8000 | 8000 | 4970 |

| 800,000–899,999 | 3500 | 3870 | 8000 | 9000 | 5264 |

| 900,000–1,000,000 | 3500 | 5400 | 8000 | 9000 | 6230 |

| 1,000,001–3,000,000 | 5000 | 5400 | 8000 | 11,100 | 6580 |

| 3,000,001–10,000,000 | 5000 | 5400 | 10,000 | 11,100 | 7000 |

Source: Mobile money agent (M-Pesa tariffs are displayed in mobile money booths).1

Note: All these fees and the levy include the government’s VAT at 18%.

A Robin Hood tax?

Waris (2021) has called solidarity taxes charged to rich people a ‘Robin Hood’ tax in the sense of taking from the rich and redistributing to the poor. In Tanzania, the taxes are charged on all users of mobile financial services and phone services, although most of the users could not afford to use the services offered at established financial institutions: these are people who are poor or at risk of being pushed back to extreme poverty from the impact of Covid-19. The lowest threshold for transactions – the lowest amount that can be sent from one network to another or withdrawn – is TSh50 (US$0.02) for Ezy Pesa, TSh100 (US$0.04) for Halopesa, Tigo Pesa, T-Pesa and Airtel Money, while M-Pesa sets its lowest amount at TSh200 (US$0.08): a customer cannot transact less than the lowest amount indicated, and in fact the lowest amount is so low as not to be practically useful – for example, TSh200 can buy one lollipop. The solidarity tax affects the people who were not able to benefit from the financial services offered by the established financial institutions such as commercial banks which dominate the financial market (Agénor and Montiel 2008).

The immediate impact on transactions and excise duty

After the introduction of the government levy on transactions, people became discouraged and the volume of transactions decreased: from June to August 2021 there was a decrease of 41% on average, but from August to December it fell by 14% as a result of the adjustments that were effected after the complaints of people, resulting in the government reducing the tax by 31%. The effects of the change are visible in the transactions and on excise duty on money transfers, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The costs for sending and receiving money are given by every mobile company in Tanzania, and the money agents display the fliers showing the costs. The documented government levy was adjusted on 31 August 2021 after the president ordered that the levy on transactions be minimised: this was gazetted on 1 September 2021. Table 3 shows the government levy before and after the changes, and Figure 2 shows the trends of total monies transacted from January 2021 to December 2021.

Trends in total value of transactions, January to December 2021 (in TSh millions). Source: Bank of Tanzania n.d.

Excise duty on money transfers (in TSh millions, June to September 2021). Source: Tanzania Revenue Authority (2022).

Evolution of government taxes on money transfers in 2021.

| Amount in Tanzanian Shillings | July–August 2021 | Adjusted in September 2021 | Adjustment in TSh | Adjustment in % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100–999 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1000–1999 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 45 |

| 2000–2999 | 16 | 11 | 5 | 42 |

| 3000–3999 | 27 | 19 | 8 | 44 |

| 4000–4999 | 56 | 39 | 17 | 43 |

| 5000–6999 | 100 | 70 | 30 | 42 |

| 7000–9999 | 125 | 88 | 37 | 43 |

| 10,000–14,999 | 320 | 224 | 96 | 43 |

| 15,000–19,999 | 610 | 427 | 183 | 43 |

| 20,000–29,999 | 960 | 672 | 288 | 43 |

| 30,000–39,999 | 1100 | 770 | 330 | 43 |

| 40,000–49,999 | 1500 | 1050 | 450 | 43 |

| 50,000–99,999 | 2050 | 1435 | 615 | 43 |

| 100,000–99,999 | 2530 | 1771 | 759 | 43 |

| 200,000–299,999 | 2940 | 2058 | 882 | 43 |

| 300,000–399,999 | 3500 | 2450 | 1050 | 43 |

| 400,000–499,999 | 4100 | 2870 | 1230 | 43 |

| 500,000–599,999 | 5200 | 3640 | 1560 | 43 |

| 600,000–699,999 | 6400 | 4480 | 1920 | 43 |

| 700,000–799,999 | 7100 | 4970 | 2130 | 43 |

| 800,000–899,999 | 7520 | 5264 | 2256 | 43 |

| 900,000–1,000,000 | 8900 | 6230 | 2670 | 43 |

| 1,000,001–3,000,000 | 9400 | 6580 | 2820 | 43 |

| 3,000,001–10,000,000 | 10,000 | 7000 | 3000 | 43 |

Source: Data recorded by author.2

Excise duty on money transfers is paid by the banks, financial institutions and telecommunications service providers. It became effective on 1 July 2014, and they are required to pay 10% to the Tanzania Revenue Authority. Figure 3 shows that the excise duty on money transfers has also decreased comparing June 2021 to the subsequent months.

The transaction levy on mobile money for sending and withdrawing is TSh24,495.4 million for August and TSh39,913.7 million for September 2021. This means that the excise duty paid by the telecommunication companies has decreased as a result of the decrease in mobile transactions, but that the big burden is borne by the people who make the transactions.

Conclusion

A solidarity tax has often been applied in countries with a high tax-to-GDP ratio, during emergencies, and is seen as a Robin Hood tax providing an opportunity to take from the rich to help the poor. It has been found to be different in Tanzania, where the tax-to-GDP ratio is below the recommended level, where the informal sector and the poor have been disproportionately impacted, and excise duty on money transfers has been reduced by 9% in July 2021, 11% in August 2021 and after the adjustment of the transaction levy the excise duty has shown to increase by 8%.

The government said that the solidarity tax was necessary to meet the cost of social spending, but I have suggested that the state could more effectively have met spending needs by improving the tax system, which would also improve the tax-to-GDP ratio. There is certainly a need to improve the tax regime in the oil and gas sector. People who lacked access to financial services from commercial banks have been accessing mobile financial services, improving their limited financial inclusion, but this has been negatively affected by the solidarity tax.