Introduction

Fractional flow reserve (FFR)-guided percutaneous coronary intervention has been shown to identify coronary stenosis that will benefit from early revascularization (intermediate coronary stenosis with positive FFR) and safely defer revascularization for intermediate coronary stenosis with negative FFR [1–3]. Despite the extensive evidence for FFR in guiding revascularization therapy in coronary artery disease, the utility of FFR assessment before percutaneous coronary intervention is only 6.1% according to the National Cardiovascular Data Registry in the United States [4]. The reason for this is mostly due to the high cost (especially in multilesion and multivessel coronary artery stenosis) and laboriousness of the procedure and possible systemic adverse effects of adenosine administration, such as bradyarrhythmia, chest pain, or bronchospasm. Hence many studies have been conducted to look at the “drug-free” functional assessment of intermediate coronary artery lesions, such as the resting time-averaged distal coronary pressure (Pd) to mean aortic pressure (Pa) ratio, the instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR), and contrast FFR [5–9].

The RXi™ system (ACIST Medical Systems, Eden Prairie, MN, United States) is a new FFR technology that uses an ultrathin monorail microcatheter (Navvus®) with an optical pressure sensor located close to the distal catheter tip. Navvus® microcatheter assessments of lesions in vessels of at least 2.5-mm diameter were comparable to those obtained with a pressure wire (Certus™ versions 6, 7, or 8; St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, United States) [10]. The potential advantages of the use of a monorail pressure microcatheter over a standard pressure wire include less signal drift, the ability to use coronary guidewire appropriate for the patient’s anatomy with better torque and navigability, the ability to move the sensor up and down the artery to determine the site of change in pressure gradient without losing wire position, and the ability to perform percutaneous coronary intervention if needed. In the ACCESS-NZ trial, it was also noted that resting Pd/Pa measured with use of a Navvus® microcatheter has a predictive value for adenosine-stressed FFR measured with use of a pressure wire: Pd/Pa of more than 0.97 will always correspond to a normal FFR (>0.80) and Pd/Pa of less than 0.90 will always correspond to an abnormal FFR (≤0.80). Studies on the predictive value of “drug-free” functional assessment of intermediate coronary artery stenosis, such as by resting Pd/Pa, contrast FFR, and iFR, have been done with the conventional pressure wire [5–9]. However, the predictive value of resting Pd/Pa for hyperemic FFR assessed with use of the monorail pressure microcatheter in real-world practice is unknown.

Materials and Methods

We prospectively enrolled 116 consecutive patients undergoing coronary angiogram and FFR assessment with use of a monorail pressure microcatheter during routine clinical practice at Sarawak Heart Centre from March 2016 to December 2017. We excluded patients with contraindications to adenosine (e.g., asthma, severe chronic obstructive lung disease, heart rate less than 50 beats per minute, systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg) and studies on infarct-related arteries. A total of 191 FFR data sets were obtained. Thirty-four lesions were excluded from the analysis either because of no hyperemic FFR (abnormal resting Pd/Pa, n=31) or incomplete data (n=3). After exclusions, 157 FFR data sets from 103 patients were included in the analysis. This study was approved by the Medical Research and Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health, Malaysia (NMRR-16-2007-32023).

Invasive coronary angiography was performed by the standard technique via a radial or femoral approach with a 5-French diagnostic catheter followed by a 6-French guiding catheter. At least four views of the left coronary system and two views of the right coronary system were acquired. Intermediate coronary artery stenosis was defined as diameter stenosis of 30–80% by visual estimation by experienced interventional cardiologists. Coronary angiograms were analyzed with Syngo QCA (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany).

Anticoagulation (heparin 80–100 units per kilogram intra-arterially) was administered before engagement of the coronary arteries with the guiding catheter. The intracoronary use of nitroglycerin (100–200 μg) and the selection of the coronary wire were per the operators’ discretion. The method of preparation and measurement with the monorail pressure catheter was described in a previous study [10]. The resting Pd/Pa was calculated from at least five cardiac cycles. Hyperemia was induced by the intracoronary administration of adenosine at a dose of 30–100 μg for the right coronary artery (RCA) and 60–200 μg for the left coronary artery. Hyperemic FFR was taken as the lowest stable value of Pd/Pa during maximal hyperemia.

With hyperemic FFR as the reference, the primary end point of the study was to identify the resting Pd/Pa value that best predicts positive hyperemic FFR of 0.80 or less. Secondary end points were to assess the positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), sensitivity, and specificity of different resting Pd/Pa values in predicting positive hyperemic FFR of 0.80 or less.

Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for windows, version 20 (Armonk NY: IBM Corp). Descriptive statistics are reported as the number with the percentage or the mean with the standard deviation, whichever is appropriate. Categorical variables were analyzed by the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were analyzed by the independent Student t test. The receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve was used to analyze the predictive value of resting Pd/Pa for a abnormal hyperemic FFR result.

The prevalence of disease was estimated to be 30% on the basis of our local experience. Hence a sample size of 157 lesions (including 62 lesions with positive FFR) was sufficient to achieve a minimum power of 80% (actual power 80.7%) to detect a change in the sensitivity from 0.70 to 0.90 on the basis of a target significance level of 0.05 (actual P=0.048) and a minimum power of 80% (actual power 0.819) to detect a change in the specificity from 0.80 to 0.90 on the basis of a target significance level of 0.05 (actual P=0.040). The minimum sample size required was calculated with the software program PASS [11].

Results

The baseline characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. The age of the patients was 57±10 years, with a mean body mass index of 26.5 kg/m2. Thirty-six percent of the patients had diabetes mellitus and 37.9% had a history of myocardial infarction. Forty-six percent of the patients had Canadian Cardiovascular Society class I angina, and most of the patients had New York Heart Association class I disease (82.5%). The target vessels were the left main stem (LMS) coronary artery in 5.7% of patients, the left anterior descending (LAD) artery in 70.7% of patients, the left circumflex (LCX) artery in 8.9% of patients, and the RCA in 14.6% of patients. The volume of contrast medium used was 108.6±55 mL per procedure (Table 1).

Baseline Demographic and Angiographic Data.

| Demographic data (n=103) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 57.35 (10.35) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 88 (85.4) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 70.41 (14.32) |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 162.92 (8.35) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26.49 (4.97) |

| LVEF (%), mean (SD) | 55.51 (14.87) |

| Smoker, n (%) | |

| Never | 42 (40.8) |

| Former | 40 (38.8) |

| Current | 21 (20.4) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 69 (67.0) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 74 (71.8) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 36 (35.0) |

| Family history, n (%)* | 21 (20.4) |

| MI history, n (%) | 39 (37.9) |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 15 (14.6) |

| CVA, n (%) | 1 (1.0) |

| PVD, n (%) | 0 (0) |

| CKD, n (%) | 5 (4.9) |

| NYHA class, n (%) | |

| I | 85 (82.5) |

| II | 18 (17.5) |

| CCS class, n (%) | |

| Asymptomatic | 49 (47.6) |

| I | 47 (45.6) |

| II | 7 (6.8) |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 24 (23.3) |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 1 (1.0) |

| Sinus rhythm, n (%) | 102 (99.03) |

| Radial access, n (%) | 88 (85.4) |

| Contrast volume (mL), mean (SD) | 108.61 (55.26) |

| Fluoroscopy time (min), mean (SD) | 12.45 (7.14) |

| Coronary angiography data (n=157) | |

| Coronary artery, n (%) | |

| Left main stem coronary artery | 9 (5.7) |

| Left anterior descending artery | 111 (70.7) |

| Left circumflex artery | 14 (8.9) |

| Right coronary artery | 23 (14.6) |

| Lesion length (mm), n (%) | |

| <10 | 79 (50.3) |

| 10–19 | 62 (39.5) |

| ≥20 | 16 (10.2) |

| Diameter stenosis (%), n (%) | |

| 30–49 | 19 (12.1) |

| 50–69 | 98 (62.4) |

| 70–80 | 40 (25.5) |

BMI, Body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; SD, standard deviation.

*Family history refers to family history of premature cardiovascular disease (1st degree relative with either MI or stroke; <55yo if Male & <65yo if Female).

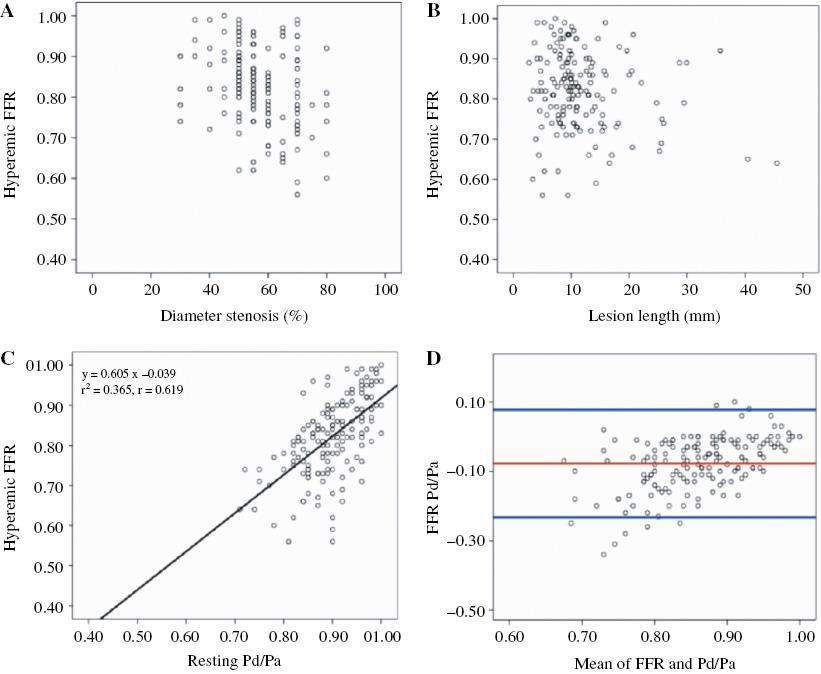

Of the 157 lesions studied, 62 were considered functionally abnormal on the basis of hyperemic FFR of 0.80 or less. The scatter plots for the percent diameter stenosis versus hyperemic FFR as well as lesion length versus hyperemic FFR showed a poor linear relationship (Figure 1A and B). With 50% or more percent diameter stenosis as the cutoff, 81 of 138 anatomically significant lesions (≥50% diameter stenosis; 58.7%) had hyperemic FFR greater than 0.80, and 5 of 19 anatomically insignificant lesions (<50% diameter stenosis; 26.3%) had hyperemic FFR of 0.80 or less (reverse mismatch). With 70% or more percent diameter stenosis as the cutoff, 37.5% of anatomically significant lesions (≥70% diameter stenosis) had hyperemic FFR greater than 0.80, and 31.6% of anatomically insignificant lesions (<70% diameter stenosis) had hyperemic FFR of 0.80 or less.

(A) Scatter plot of the percent diameter stenosis versus hyperemic fractional flow reserve (FFR) (r=−0.337, P<0.001). (B) Scatter plot of the lesion length versus hyperemic FFR (r=−0.159, P=0.046). (C) Scatter plot of the resting time-averaged distal coronary pressure to mean aortic pressure ratio (Pd/Pa) versus hyperemic FFR (r=0.619, P<0.001). (D) Bland-Altman plot demonstrating poor agreement between resting Pd/Pa and FFR.

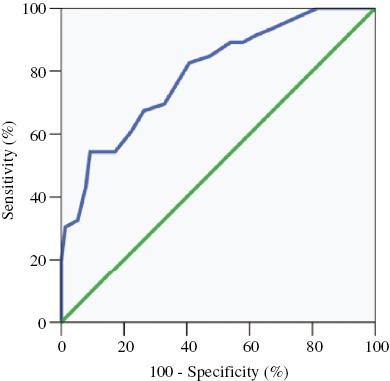

Pearson correlation analysis and the Bland-Altman plot showed poor agreement between resting Pd/Pa and hyperemic FFR (r=0.619, P<0.001) (Figure 1C and D). The agreement was more scattered with lower resting Pd/Pa and FFR (Figure 1C). The ROC curve had an area under the curve of 0.800 (95% confidence interval 0.732–0.868, P<0.001) for resting Pd/Pa to predict positive FFR (≤0.80) (Figure 2). Resting Pd/Pa of less than 0.85 had the greatest diagnostic accuracy at 74.5%. The coordinates of the ROC curve showed that certain resting Pd/Pa cutoffs had diagnostic performance that may preclude the use of hyperemic FFR (Table 2).

Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve for Resting Time-Averaged Distal Coronary Pressure to Mean Aortic Pressure Ratio with Fractional Flow Reserve of 0.80 or Less as the Reference.

The area under the curve is 0.800 (95% confidence interval 0.732–0.868, P<0.001).

Criterion Values and the Coordinates of the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve.

| Criterion | PPV (%) | Specificity (%) | NPV (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Diagnostic accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.81 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 65.1 | 17.7 | 67.5 |

| ≤0.82 | 94.1 | 98.9 | 67.1 | 25.8 | 70.1 |

| ≤0.83 | 81.0 | 95.8 | 66.9 | 27.4 | 68.8 |

| ≤0.84 | 75.9 | 92.6 | 68.6 | 35.5 | 70.1 |

| ≤0.85 | 78.9 | 91.6 | 73.1 | 48.4 | 74.5 |

| ≤0.86 | 68.2 | 85.3 | 71.7 | 48.4 | 70.7 |

| ≤0.87 | 65.4 | 81.1 | 73.3 | 54.8 | 70.7 |

| ≤0.88 | 65.0 | 77.9 | 76.3 | 62.9 | 72.0 |

| ≤0.89 | 61.1 | 70.5 | 78.8 | 71.0 | 70.7 |

| ≤0.90 | 58.1 | 62.1 | 83.1 | 80.6 | 69.4 |

| ≤0.91 | 55.9 | 56.8 | 84.4 | 83.9 | 67.5 |

| ≤0.92 | 54.4 | 50.5 | 88.9 | 90.3 | 66.2 |

| ≤0.93 | 52.8 | 42.1 | 89.8 | 91.9 | 64.3 |

| ≤0.94 | 50.4 | 40.0 | 90.5 | 93.5 | 61.1 |

| ≤0.95 | 49.6 | 36.8 | 92.1 | 95.2 | 60.0 |

| ≤0.96 | 46.6 | 25.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 54.8 |

| ≤0.97 | 44.6 | 18.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 51.0 |

| ≤0.98 | 41.6 | 8.4 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 44.6 |

| ≤0.99 | 40.5 | 4.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 42.0 |

NPV, Negative predictive value; PPV positive predictive value.

The resting Pd/Pa was 0.96 or less in 133 of 157 lesions (84.7%). Pd/Pa of 0.96 or less had a sensitivity of 100%, NPV of 100%, specificity of 25.3%, and PPV of 46.6% in predicting abnormal FFR. Subgroup analysis for the diagnostic accuracy showed consistent results regardless of the vessels studied (LMS coronary artery/LAD artery or LCX artery/RCA), the location of lesions (proximal or mid/distal), and the severity of stenosis (<50% or ≥50%) (Table 3).

Subgroup Analysis Results for Time-Averaged Distal Coronary Pressure to Mean Aortic Pressure Ratio of 0.96 or Less.

| Diseased vessel | Lesion location | Diameter stenosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMS/LAD (n=120) | RCA/LCX (n=37) | Proximal (n=73) | Mid/distal (n=84) | <50% (n=109) | ≥50% (n=48) | |

| PPV | 53.2% | 13.6% | 41.5% | 51.5% | 38.3% | 66.7% |

| Specificity | 14.8% | 44.1% | 17.4% | 32.7% | 20.5% | 40.9% |

| NPV | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| Sensitivity | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

LAD, Left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; LMS, left main stem coronary artery; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; RCA, right coronary artery.

The resting Pd/Pa was 0.82 or less in 17 of 157 lesions (10.8%). Pd/Pa of 0.82 or less had a specificity of 98.9%, PPV of 94.1%, NPV of 67.1%, and sensitivity of 25.8% in predicting abnormal FFR. Subgroup analysis for the diagnostic accuracy showed consistent results regardless of the vessels studied (LMS coronary artery/LAD artery or LCX artery/RCA), the location of lesions (proximal or mid/distal), and the severity of stenosis (<50% or ≥50%) (Table 4).

Subgroup Analysis Results for Time-Averaged Distal Coronary Pressure to Mean Aortic Pressure Ratio of (Pd/Pa) of 0.82 or Less.

| Diseased vessel | Lesion location | Diameter stenosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMS/LAD (n=120) | RCA/LCX (n=37) | Proximal (n=73) | Mid/distal (n=84) | <50% (n=109) | ≥50% (n=48) | |

| PPV | 94.1% | –* | 100% | 90.0% | 90.0% | 100.0% |

| Specificity | 98.4% | 100% | 100% | 98.0% | 98.6% | 100.0% |

| NPV | 58.3% | 91.9% | 69.7% | 64.9% | 72.7% | 53.7% |

| Sensitivity | 27.1 | –* | 25.9% | 25.7% | 25.0% | 26.9% |

LAD, Left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; LMS, left main stem coronary artery; RCA, right coronary artery.

*No Pd/Pa of 0.82 or less.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the predictive value of resting Pd/Pa for hyperemic FFR assessed with use of a monorail pressure microcatheter in real-world practice. The main finding of this study showed that there was a poor agreement between resting Pd/Pa and hyperemic FFR assessed with use of the microcatheter. The correlation was lower than in other studies using a conventional pressure wire [5, 8, 12, 13]. Because of the poor agreement between resting Pd/Pa and hyperemic FFR, the utility of microcatheters in other methods of “drug-free” functional assessment of intermediate lesions, such as contrast FFR, iFR, and the resting full-cycle ratio, should to be regarded with caution.

However, careful examination of the resting Pd/Pa coordinates of the ROC curve identified certain resting Pd/Pa values that could reliably preclude the need for hyperemic FFR. We found that resting Pd/Pa of 0.96 or greater will invariably correspond to a normal hyperemic FFR, and resting Pd/Pa of less than 0.82 will have high specificity (98.7%) and PPV (93.3%) to predict abnormal FFR. By applying the results of these findings to our cohort of patients retrospectively, we were able to preclude the need for hyperemic FFR in 40 of 157 lesions (25.4%). In other words, a quarter of the functional assessment for intermediate lesions could be done reliably without the use of intracoronary administration of adenosine. The high accuracy of resting Pd/Pa of 0.96 or greater to predict a normal hyperemic FFR was consistent regardless of the vessel studied, the location of the lesion (proximal vs. distal), and the severity of stenosis. In comparison, it was reported that for proximal stenosis in the large coronary arteries (LMS coronary artery and proximal portion of the LAD artery), contrast FFR and iFR were discordant with FFR in up to 20 and 30% of patients, respectively [14].

In the ACCESS-NZ trial, it was observed that resting Pd/Pa of more than 0.97 will invariably correspond to a normal hyperemic FFR (>0.80) and Pd/Pa of less than 0.90 will always correspond to an abnormal hyperemic FFR (≤0.80). Our study found a similar cutoff for resting Pd/Pa (≥0.96) to predict normal hyperemic FFR, but a lower cutoff for resting Pd/Pa (≤0.82) to predict abnormal hyperemic FFR. One possible explanation for the disparity of the lower cutoff value is the difference in the study population: our patients represent real-world practice in which one-third of them had some degree of microvascular dysfunction (37.9% had a history of myocardial infarction and 36% had diabetes mellitus). Microvascular bed dysfunction can lead to resistance or unresponsiveness to intracoronary adenosine, resulting in a lower cutoff value for resting Pd/Pa to predict abnormal hyperemic FFR.

Previous studies looking at the predictive value of resting Pd/Pa assessed with a conventional pressure wire found different cutoffs of more than 0.95 and 0.88 or less [8]. We postulate that such a difference could be due to the profile of the microcatheter (0.022 in.), whereby the addition of the microcatheter would have a greater effect on flow across the stenosis, leading to lower resting Pd/Pa and FFR compared with the conventional pressure wire (0.014 in.). The difference in FFR between microcatheter and pressure wire measurement was reported to be as much as −0.04 [15]. However, the clinical impact of this difference appears to be minimal in most cases [16].

Our findings have a few clinical implications. First, we found poor agreement between resting Pd/Pa and hyperemic FFR assessed with use of the microcatheter. Hence other “drug-free” functional assessments using a monorail microcatheter have to be interpreted with caution. Second, certain resting Pd/Pa values may preclude the need for adenosine FFR assessment: resting Pd/Pa of 0.96 or greater will invariably correspond to a normal FFR and resting Pd/Pa of 0.82 or less has a high specificity and PPV for abnormal FFR. These findings could potentially result in a quarter of functional assessments for intermediate lesions reliably being done with use of resting Pd/Pa alone. The advantages of the predictive value of resting Pd/Pa over other “drug-free” functional assessments of intermediate coronary artery stenoses, such as contrast FFR and iFR, include less contrast medium use, less time required, fewer systemic adverse effects of adenosine administration, and greater cost-effectiveness. Besides, the current monorail pressure microcatheter system does not support measurement of iFR. This finding will be useful for operators measuring FFR using a monorail pressure microcatheter, especially for resting Pd/Pa of 0.96 or greater.

Our study has several limitations. First, most (90.4%, 142 of 157 lesions) of the intermediate coronary artery stenoses in this study had percent diameter stenosis of 40–70%. A smaller proportion, 5.7% (7 of 122 lesions), had percent diameter stenosis of 30–39%, and 6.5% (8 of 122 lesions) had percent diameter stenosis of 71–80%. Hence the predictive value of the extreme ends of these coronary artery stenoses has to be interpreted with caution. Second, we used intracoronary administration of adenosine rather than intravenous administration of adenosine. This is because intravenous administration of adenosine is more expensive and more time-consuming in our hospital setting. Nevertheless, intracoronary administration and intravenous administration of adenosine yield similar FFR values and show comparable long-term prognostic utility in the deferred population [17]. Thirdly, our study did not assess coronary arteries with reference vessel diameter of less than 2.5 mm. This was because the monorail pressure microcatheter is not validated for coronary artery vessels of diameter less than 2.5 mm. Lastly, even though our study showed that certain resting Pd/Pa values could reliably preclude the need for adenosine FFR, clinical outcome studies are required to explore whether these resting Pd/Pa values might obviate the need for hyperemic FFR in selected patients, similarly to the DEFINE FLAIR and iFR-SWEDEHEART studies [18, 19].

Conclusion

Resting Pd/Pa showed poor agreement with hyperemic FFR assessed with use of a monorail pressure microcatheter. However, resting Pd/Pa of 0.96 or greater had excellent sensitivity and NPV to predict normal hyperemic FFR, and resting Pd/Pa of 0.82 or less had excellent specificity and PPV to predict abnormal hyperemic FFR.