Introduction

Historically, medicine has been an endeavor in which the physician spends tens of thousands of hours learning an intricate trade and after completion of training goes into practice to heal. Most physicians committed to the ideal of lifelong learning continue to adapt and grow their skills. Few, however, are formally taught how to critically appraise the care they provide or how to systematically approach improving care. Quality improvement (QI) has become a key part of the discussion about transforming health care [1]. Educational accrediting bodies, such as the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education and the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, require teaching of QI and patient safety [2, 3]. Thus, a concurrent growth has occurred in the use of QI methods for improving care across a wide spectrum of practice settings, specialties, and illnesses [4].

This review discusses the current state of QI as it relates to cardiovascular (CV) imaging. The topics include an overview of QI methods, options for learning and teaching QI methods, examples of successful and unsuccessful QI projects in CV imaging, and the barriers to and rewards of working on QI.

QI Methods

One of the traditional places to begin the story of how QI was embraced by the modern world is with W. Edwards Deming. Deming helped popularize methods of statistical process control and continuous improvement [5]. Statistical process control refers to the use of statistics to monitor a process and limit variation from the desired result. Examples of statistical process control in medicine include measuring door-to-balloon time, 30-day readmissions after heart failure, and the rate of rarely appropriate cardiac imaging.

Continuous improvement describes the process of conducting cyclical interventions to achieve gradual improvements: plan a change by observing a process, do that change, study the effect of the change, and have the organization act on the change (PDSA). By continually performing PDSA cycles, an organization can improve the process under study. With door-to-balloon time as an example, an organization seeking to improve could reorganize its call schedules, then allow emergency medical services to activate the catheterization laboratory, bypassing the emergency department for ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients while studying the effect on door-to-balloon times with each change.

These concepts form the core of commonly applied contemporary QI approaches such as Lean, Six Sigma, and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Model for Improvement. Some of these approaches have come to medicine from manufacturing industries; both revolve around complex processes that generate inefficiency and variation. Each approach has its own strengths; some are better suited for specific challenges in medicine than others.

Lean is a production philosophy focused on eliminating waste, which might include unnecessary steps, redundant processes, or delays [6, 7]. Take the process of admitting a patient from the emergency department as an example of how Lean might be useful. This seemingly simple task typically involves multiple physicians, nurses, custodial staff, transportation staff, and nursing/patient assistants. It will span multiple floors, if not buildings. Effective communication needs to occur in a timely fashion on multiple levels. Mapping that process out often reveals wasteful steps that could be eliminated to increase efficiency.

Six Sigma refers to organizations setting a goal of having minimal defects in their manufacturing processes; six standard deviations (sigma) refers to having fewer than 3.4 defects per million, or 99.99966% success [8, 9]. To achieve this, Six Sigma endorses a cycle of define, measure, analyze, improve, and control (DMAIC). In medicine, it may seem that few processes are consistent enough to consider achieving Six Sigma reliability; however, avoiding allergic reactions, assigning laboratory results to the correct patient, and dispensing pharmaceuticals are all appropriate targets for exceptional reliability.

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement was founded in 1991 by leaders seeking to rebuild a health care system with minimal waste, delay, injustice, and harm. The organization promotes its own approach to QI called the Model for Improvement [10–12]. Built on Deming’s principles, this model asks users to establish a goal, define success, and plan changes that are implemented with use of PDSA cycles.

QI Teaching

Many options exist for teaching QI to health care professionals. As previously noted, both medical students and residents/fellows are expected to receive some type of QI education during their training. The form of that training is highly variable, ranging from low-impact didactics through intensive, applied QI experiences. Various curricula are published in the medical educational literature; in general, the efforts are successful but require close attention to a multitude of environmental factors [13–16].

While individual training institutions often create their own curricula suited to their local learners’ needs, formal training in Lean, Six Sigma, and the Model for Improvement is available as well. Lean and Six Sigma are sometimes combined in medicine, where learners of these parallel skill sets earn “belts” depending on the skills they have mastered and implemented at their facility. The belts are organized in a hierarchy where progressive achievement in QI accompanies a graded responsibility to teach skills to others. A yellow belt refers to someone who is aware of Lean/Six Sigma principles, conducted a small-scale QI project, and reported the results in a standardized format. A green belt is earned with the application of a wider set of skills and principles in accomplishing a larger-scale project. A black belt is earned by those who are working on QI in a full-time or nearly full-time position. After more than 2 years of black belt service, one can earn the title of Master Black Belt. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement offers its own comprehensive suite of educational materials for individuals or institutions, and sponsors educational meetings for professionals [17].

Other venues for formal training combine QI methods or focus on “teaching the teachers” to spread QI methods. Examples include “Practical Improvement Science in Health Care” and “Fixing Healthcare Delivery,” which are massive open online courses [18, 19]. The American Association of Medical Colleges has a certificate program called Teaching for Quality, and the Quality and Safety Educators Academy is an intensive workshop sponsored by the Society for Hospital Medicine [20, 21].

QI Projects in CV Imaging

The processes of ordering, performing, interpreting, and reporting on CV imaging tests provide ample opportunity for QI activities. Using the six domains of health care quality from the Institute of Medicine, we can define and provide examples of how QI can be applied in the world of CV imaging (Figure 1). Study and implementation of appropriate use criteria is an obvious example relating to efficiency. Despite ample training during fellowship, many studies have documented substantial variability between readers in CV image interpretation, an opportunity to increase effectiveness. Radiation reduction techniques for CV imaging have been a key element in recent discussions about patient safety. The American College of Cardiology endorsed a similar “Dimensions of Care” in describing how quality in CV imaging can be enhanced through a methodical approach to each step of the imaging process from order entry through to final reporting [22].

The Six Domains of Healthcare Quality and Examples of How They Apply to Cardiovascular Imaging.

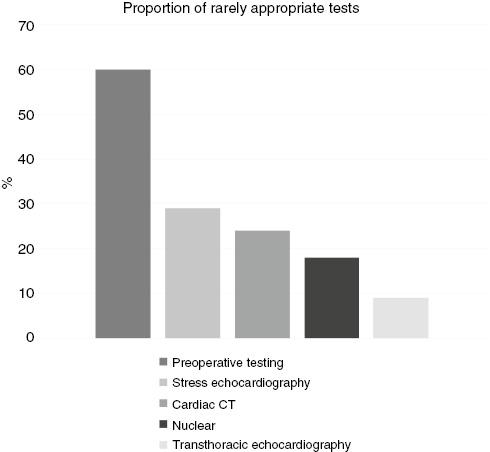

Appropriate use criteria were first published by the American College of Cardiology in 2005, and they provided some standard definitions for low-value care. Since then, physicians have been developing strategies to implement them into practice. Despite such efforts, substantial gaps remain [23–26] (Figure 2). Numerous interventions using educational techniques, redesign of order entry systems, and audit and feedback processes have been reported [27–29]. A systematic review of QI interventions aimed at reducing inappropriate imaging found that audit and feedback was the most effective technique adopted [30].

Variability is manifest in several domains related to CV imaging. Some targets for improvement include reducing variation between two people reading the same study (interobserver variation), reducing variation when the same person reads a study twice (intraobserver variation), and increasing the accuracy of measurements in comparison with an external reference. Interobserver variation decreases with well-designed educational interventions. One echocardiography laboratory implemented a case-based didactic conference and observed a 40% relative reduction in variation of left ventricular ejection fraction assessment (±14 to ±8.4%, P=0.007) [31]. Another laboratory adopted a “QI bundle” to reduce variation of image acquisition by technologists and successfully improved image quality for both intracardiac and extracardiac structures [32]. A similar project incorporated education and audit and feedback, targeting both physicians and technologists to successfully increase correlation between echocardiography-derived and catheterization-confirmed hemodynamic measurements [33].

Radiation exposure is a persistent concern with CV imaging because of the low, but nonzero, risk of future malignancy. CV imaging that involves radiation exposure should be performed under the principle of “as low as reasonably achievable” (ALARA). With nuclear cardiac imaging, several strategies can be applied to reduce the radiation dose. One of the most effective is referred to as stress-first or stress-only perfusion imaging. With this strategy, the stress portion of a myocardial perfusion test is performed first, and if the images show no defects, rest imaging can be avoided. A recent implementation of this strategy demonstrated an 80% reduction in median radiation dose (14.1 mSv vs. 2.8 mSv, P<0.0001) [34]. This approach has been widely adopted in Europe (84.4% stress-first studies) and elsewhere around the globe; however, North America lags substantially, with only 7.7% of myocardial perfusion studies being done as stress-first studies [35].

Path to Improving CV Imaging

Gaps in care are highly variable across practice settings. One facility may have substantial challenges with rarely appropriate testing, while another’s primary issue may be completing reports in a timely fashion. A single group of physicians with similar practice habits may struggle with promoting quality at different facilities depending on the available resources and appetite for change at each. We do not think there is an ideal practice for solving CV imaging quality problems because the solutions may be diverse depending on the variables involved, such as the ordering clinicians, furnishing clinicians, technologists, available equipment and software, workflows, reporting mechanisms, and clinical demands. In our opinion, the best path forward is one where all physicians are attuned to improving the care they deliver and are willing to collaborate in multidisciplinary, physician-led teams to tackle multiple issues simultaneously and on the basis of some determination of the relative priority of the issues (Figure 3).

One ideal to strive for is identifying a physician who is responsible for improving quality and also has decision-making authority to facilitate necessary changes.

Barriers to Conducting QI

Conducting QI is challenging; while many barriers are intuitive, they have also been formally studied and described in the medical literature [36]. The first step to improvement is recognizing that there is a problem. Not so long ago, central line– and urinary catheter–related infections were often considered an unfortunate complication but an acceptable risk. Once payers began refusing to reimburse facilities for any care related to such complications, minimizing these infections became a top priority. This example reinforces the importance of having incentives aligned with quality and safety initiatives. Incentives need to be provided for the staff working on QI projects, who are often doing so in addition to their busy clinical duties. An often-overlooked issue is developing a system for consistent collection of meaningful data, without which a QI project cannot demonstrate effectiveness. Fortunately, many hospitals, clinics, and medical centers have developed teams of professionals who either directly conduct QI or provide assistance to motivated teams who want to improve their local care environments.

Rewards of Conducting QI

Despite these barriers, QI is feasible to undertake in essentially all CV imaging environments and it is associated with several potential rewards. First and foremost, of course, are the direct and indirect benefits to patients: timeliness of care, safety, and accuracy of findings. For the individual physician or nurse, participation in QI provides a sense of meaning and accomplishment that augments the satisfaction of providing good patient care. Institutions often develop programs to provide recognition for high achievement in QI that sometimes includes financial rewards. The Choosing Wisely campaign, which encourages patients and physicians to ask questions about low-value care, sponsors the Choosing Wisely Champions program [37]. Through this program, individual physician specialty societies are invited to conduct competitions to recognize QI teams in their area of expertise. Both the American Society of Echocardiography and the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology have such competitions. The Florida Chapter of the American College of Cardiology celebrates QI through submissions from members about their local QI initiatives [38].

Take-Home Points

QI came to health care from the industrial sector with the goals of reducing waste and unwanted variation in care delivery processes. Over the past few decades, QI has been integrated into most health care facilities and is an educational mandate for all physician trainees. Numerous examples of how QI projects have enhanced CV imaging have been published. Despite many barriers, QI is a rewarding endeavor.