Introduction

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is defined as an increase in cardiac mass with or without an accompanying increase in left ventricular wall thickness (LVWT) [1]. With the exception of highly trained athletes [2], LVH usually reflects pathologic adaptation to chronic pressure (concentric LVH) or volume (eccentric LVH) loading on the left ventricle. Although the prevalence of LVH varies according to the population studied and is significantly associated with age, sex, ethnicity, and comorbidities [3–5], contemporary data suggest an overall prevalence of 7% in a high-risk population [6].

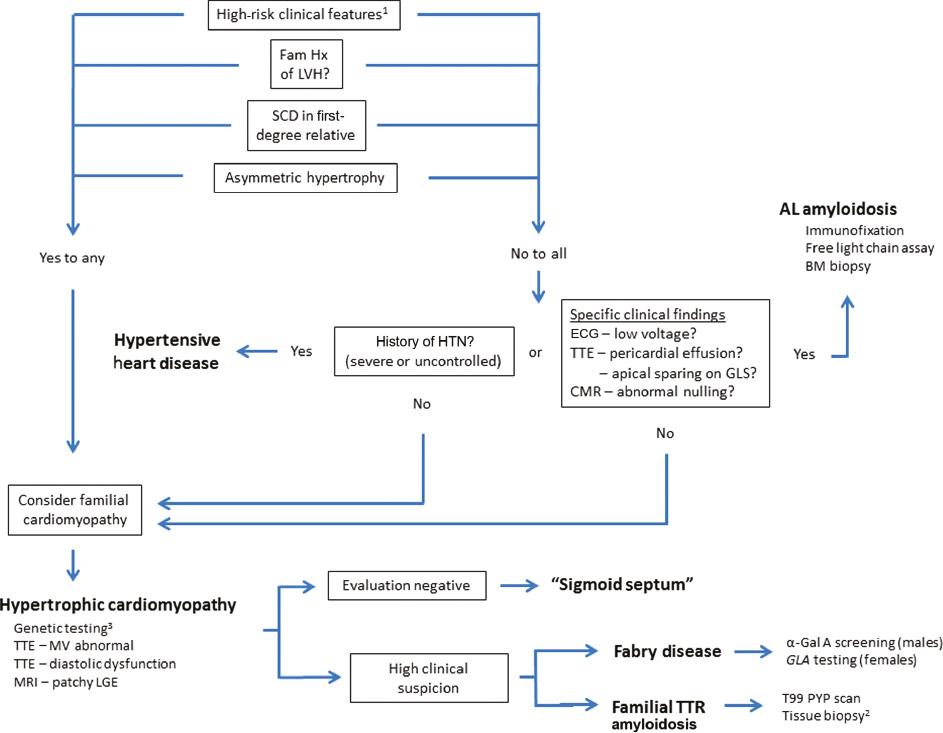

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is the most commonly used imaging modality for screening patients with suspected cardiovascular disease because of widespread availability, relatively low cost, and safety [7]. Not infrequently, LVH is identified in patients without conventional risk factors (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, degenerative heart valve disease, etc.) and poses a unique diagnostic dilemma. Multimodality imaging, including cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography, and nuclear imaging techniques, is increasingly used to further characterize cardiac structure and function and help distinguish different cardiac disorders. This article focuses on the differential diagnosis of concentric LVH with an emphasis on multimodality imaging. A diagnostic algorithm is proposed to help streamline the clinical evaluation of these patients (Figure 1).

Diagnostic Approach to Incidental Left Ventricular Hypertrophy (LVH) on Noninvasive Cardiac Imaging.

Evaluation of the patient begins with the careful taking of the clinical history and a search for “red flags,” which may include recurrent and unexplained syncope, history of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, absence of hypertension, and a family history of sudden cardiac death (SCD; first-degree family member or multiple second-degree family members) or cardiomyopathy (specifically cardiac hypertrophy). When cardiac hypertrophy is incidentally identified on echocardiography, clues to a pathologic diagnosis include asymmetric hypertrophy (particularly the ventricular septum or cardiac apex), markedly reduced mitral annular tissue Doppler velocities, abnormal global longitudinal strain (GLS), and pericardial effusion. In contrast, symmetric hypertrophy and a history of severe or uncontrolled hypertension would strongly support a diagnosis of hypertensive heart disease. Specific clinical findings that suggest amyloid light chain (AL) cardiac amyloidosis include low voltage on electrocardiogram (ECG), abnormal GLS with apical sparing and a pericardial effusion on transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), and abnormal nulling on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Sigmoid septum is frequently a diagnosis of exclusion and may require a comprehensive workup (ambulatory ECG monitoring, cardiac MRI, exercise treadmill testing, and genetic screening) to exclude sarcomere mutation-mediated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A search for less common causes (Fabry disease, transthyretin [TTR] amyloidosis, Noonan syndrome) is often based on the index of clinical suspicion, coexistent clinical findings, and/or suspicious family history. 1Syncope, personal history of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; 2tissue biopsy (fat aspirate), endomyocardial biopsy; 3negative genetic test result does not exclude the diagnosis; BM, bone marrow; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; α-Gal A, α-galactosidase A; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; MV, mitral valve; T99 PYP, technetium-99m pyrophosphate.

Nonpathologic LVH

Athlete’s Heart

In contrast to pathologic cardiac remodeling in response to increased afterload, physiologic remodeling may occur in highly trained athletes, particularly those competing in high-endurance sports such as rowing, cycling, and cross-country skiing. Athletic remodeling is nonspecific and characterized by increased LVWT (usually ≤12 mm), increased left ventricular mass, and increased left atrial volume [2, 8, 9]. Importantly, diastolic function and global longitudinal strain (GLS) are often normal (or supranormal) [10, 11]. Occasionally, late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) is identified on cardiac MRI in older athletes and is hypothesized to reflect a dose-response relationship from lifetime exposure to exercise [12]. This unique constellation of imaging findings (LVH with normal diastolic function, normal GLS, and paucity of LGE) in addition to a history of participation in a sport associated with a predominant alteration in LVWT (e.g., weight lifting, wrestling, shot put, and other isometric “power” exercises) [8] helps to distinguish athlete’s heart from other pathologic causes of LVH. A period of “detraining” and observing for regression of LVH may be necessary in the rare instance of severe LVH (LVWT >15 mm), particularly among black athletes [13].

Pathologic LVH

Hypertensive Heart Disease

Arterial hypertension remains the leading cause of preventable death worldwide and is present in up to 31% of the world’s adult population [14]. The cardiac manifestations of chronically increased left ventricular afterload include a spectrum of adaptation that ranges from left ventricular “remodeling” (characterized by an increase in relative wall thickness but preserved left ventricular mass) to concentric LVH (pathologic increase in both relative wall thickness and left ventricular mass). Identification of LVH among patients with hypertensive heart disease (HHD) is important given the adverse prognostic implications of this associated finding.

HHD is often associated with increased voltage in the precordial leads on electrocardiogram (ECG) and reflects an increase in left ventricular mass. Echocardiographic findings include increased LVWT (>12 mm), usually preserved left ventricular dimension/volume, left atrial enlargement, abnormal indices of diastolic function, and premature or advanced degenerative valve disease [15]. It is important to emphasize none of these imaging findings are specific to HHD.

Recently, asymmetric HHD has been described with a phenotype of LVH (including LVWT >15 mm) that may be indistinguishable from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) [16]. More advanced imaging techniques, such as speckle-tracking echocardiography for assessment of GLS, along with cardiac MRI for late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) and native T1 mapping, may provide clues to the presence of myocardial fibrosis [17–19], even before the development of LVH. Perhaps the most important role for GLS and LGE is the potential to distinguish HHD from other causes of LVH, notably HCM [20–23], that have differing natural history and therapeutic implications. Figures 2 and 3 summarize the GLS and LGE patterns, respectively, in different cardiac diseases.

Global Longitudinal Strain Patterns in Myocardial Disease.

Global longitudinal strain in hypertensive heart disease may show a nonspecific decrease in strain values in the setting of symmetric and concentric LV hypertrophy whereas, other myocardial diseases often reveal a characteristic strain pattern. In cardiac amyloidosis, there is often a global decrease in longitudinal strain values most notable in the basal and mid ventricular segments and relative preservation at the LV apex. Longitudinal strain values in HCM are characteristically lowest among myocardial segments with maximal hypertrophy. Longitudinal strain values in Fabry Disease are often decreased in a nonspecific pattern although some authors have identified a predilection for the posterolateral wall in small retrospective studies. HCM, Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Late Gadolinium Enhancement Patterns in Myocardial Disease.

Characteristic abnormal late gadolinium enhancement patterns in HCM include “midmyocardial” and “patchy diffuse”. Involvement of the RV insertion sites has also been described in HCM patients but is also occasionally seen in patients without evidence of myocardial disease. “Subendocardial” patterns of late gadolinium enhancement are characteristic of ischemic heart disease. HCM, Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; RV, right ventricular.

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

HCM is one of the most common causes of pathologic LVH, with an estimated prevalence as high as 1 in 200 [22]. A number of autosomal dominant mutations have been identified involving the cardiac sarcomere contractile unit with resultant cardiac myocyte hypertrophy and disarray, severe LVH (LVWT >15 mm) most often with asymmetric septal hypertrophy, and myocardial fibrosis and increased risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD). A correct and timely diagnosis of HCM is critical to risk stratification for SCD, selection of appropriate treatment options (medical therapy, septal reduction, and internal cardiac defibrillator), and family screening.

On TTE, HCM is often characterized by abnormal mechanics of myocardial relaxation, including mitral inflow Doppler E/A ratio less than 1 and reduced mitral annular myocardial tissue Doppler velocities (e’ frequently <6 cm/s), in addition to abnormal GLS (most often at the basal ventricular septum). These findings can help differentiate HCM from physiologic remodeling in athlete’s heart. The presence of an elongated anterior mitral leaflet, systolic anterior motion of the mitral apparatus, and dynamic left ventricular obstruction further supports a diagnosis of HCM, although these findings are not specific. Different phenotypes of cardiac hypertrophy are now well recognized (Figure 4), including sigmoid septal hypertrophy, neutral septal hypertrophy, “reverse curve” septal morphology, and apical variant and hypertrophy primarily involving the inferoseptum or posterolateral wall. Elevated right ventricular systolic pressure is common; however, the presence of a pericardial effusion is atypical and may be a subtle clue to an infiltrative myocardial disease (i.e., cardiac amyloidosis). LGE on cardiac MRI is identified in up to 80% of HCM patients and frequently involves the midwall and right ventricular insertion points along the ventricular septum [23]. In contrast, isolated LGE at the site of right ventricular insertion is not specific and may be seen in individuals with or without pathologic hypertrophy. Native T1 and potentially T2 mapping is an emerging cardiac MRI technique that, in the absence of LGE, may help distinguish HCM from HHD, including genotype-positive/phenotype-negative individuals, by identifying diffuse abnormalities of the myocardium (e.g., as a consequence of sarcomere mutation) [24].

The clinical history is an important adjunct to multimodality imaging in HCM. A family history of unexplained SCD and/or the identification of other family members with LVH can help refine the clinical diagnosis. Postprandial as well as heat-related exacerbation of exertional symptoms [25] is a relatively specific finding in patients with HCM, and recurrent syncope may be an ominous clinical sign of ventricular arrhythmia and the need for expedited management (internal cardiac defibrillator therapy).

Focal Septal Hypertrophy (Sigmoid Septum)

Structural changes of the heart, resulting from either physiologic (aging) or pathologic (increased afterload) mechanisms, can lead to focal septal hypertrophy (FSH), narrowing of the left ventricular outflow tract, and occasionally systolic anterior motion with dynamic left ventricular obstruction [26–28]. This constellation of findings may closely resemble HCM on TTE. Most published data predate the widespread adoption of genetic testing, and it remains unclear whether FSH represents a relatively benign age-related finding or a forme fruste manifestation of HCM [29]. Occasionally, narrowing of the left ventricular outflow tract and dynamic obstruction is observed among patients with normal ventricular wall thickness and has been attributed to hyperacute “aortoventricular” angulation (Figure 5A, arrow). This latter anatomic variant has been termed “sigmoid septum” because of the sigmoid-shaped course of blood flow during ejection into the aorta [30].

Sigmoid Septal Hypertrophy.

Focal septal hypertrophy with sigmoid shaped basal ventricular septum (arrow) is demonstrated on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (panel A) and transthoracic echocardiogram in the apical long axis view (panel B). AoV, Aortic valve; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle.

FSH manifesting itself with dynamic left ventricular obstruction poses one of the most challenging clinical conundrums. The diagnostic approach begins with the history and clarifying the age of onset, identifying comorbidities (hypertension), and exploring the family history for cardiomyopathy or unexplained death. Conceptually, HCM would be expected to manifest more ECG voltage abnormalities than FSH, although this has not been rigorously evaluated. Attempts to distinguish between FSH and HCM with echocardiography have identified statistically significant differences in mitral annular tissue Doppler velocities, lower in patients with HCM, although the large overlap between groups diminishes the specificity of this finding in the individual patient [31, 32]. GLS may show abnormal systolic velocities at the hypertrophied septum, whereas cardiac MRI findings supportive of FSH include discrete septal hypertrophy (involving one or two myocardial segments), maximal wall thickness less than 15 mm, and absence of LGE. It is important to emphasize, however, that LVH in HCM can also be highly variable, with up to 12% of patients having focal left ventricular hypertrophy (two or fewer segments) [33]. Genetic testing and ambulatory ECG monitoring may be helpful in cases of diagnostic uncertainty; however, these patients are often managed similarly to patients with HCM, including risk stratification, routine family screening, and septal reduction for refractory exertional symptoms.

Cardiac Amyloid

Cardiac amyloidosis is an infiltrative cardiomyopathy, with LVH developing as a consequence of protein deposition within the extracellular matrix of the heart. Various amyloidogenic proteins have been reported; however, the most frequently encountered subtypes causing cardiomyopathy in clinical practice are amyloid light chain (AL) amyloidosis and transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR).

Clinical manifestations and natural history differ by subtype, with earlier cardiac involvement and severer LVH in AL amyloidosis. ECG will often paradoxically show low voltage (particularly with AL cardiac amyloidosis); however, this finding is neither sensitive nor specific, with some amyloid patients demonstrating normal or increased voltage [34, 35]. TTE has a primary role in disease screening, and the diagnosis can often be inferred on the basis of noninvasive imaging. A pericardial effusion is typical, and diffuse thickening of the heart valves may also be present. The GLS pattern in AL amyloidosis is unique, with severely reduced velocities at the base and preserved left ventricular apical velocities (Figure 2). Cardiac MRI may reveal diffuse hyperenhancement with gadolinium administration as well as “abnormal nulling” on inversion recovery sequences (Video 1). The cardiac manifestations of ATTR may be overt with severe LVH or subclinical with an insidious course indistinguishable from heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. More recently, technetium-99m pyrophosphate scanning has reemerged as a sensitive and specific imaging modality for identifying cardiac involvement in ATTR [36].

Differentiation of the amyloid subtypes is important because of different treatment strategies, including chemotherapy and stem-cell transplant for the clonal plasma cell dyscrasia underlying AL amyloidosis and liver transplant for ATTR amyloidosis. Newer investigational therapies (protein-stabilizing molecules) may revolutionize the treatment and prognosis of patients with ATTR [37].

Miscellaneous Disorders

Fabry disease (FD) is an X-linked recessive lysosomal storage disorder due to insufficient activity of the GLA-encoded enzyme α-galactosidase A. Affected males frequently manifest “classic” FD characterized by progressive renal dysfunction, hypohidrosis, actinic keratosis (trunk, groin), acral paresthesias of the extremities, ischemic stroke, and severe cardiac hypertrophy. Hemizygous females may present with limited organ involvement, including isolated cardiac hypertrophy. FD typically presents with symmetric hypertrophy of both the left ventricle and the right ventricle; however, the cardiac manifestations on TTE may be indistinguishable from HCM, including asymmetric septal hypertrophy, dynamic left ventricular obstruction, and occasionally apical pouch. However, cardiac MRI may prove a useful diagnostic adjunct in this population as the elevated glycosphingolipid levels within myocardial tissue result in characteristically low native T1 values. Prompt diagnosis of FD is critical because of the availability of disease-specific therapy (recombinant α-galactosidase A replacement and more recently migalastat, an oral pharmacological chaperone of α-galactosidase A) and the need for extended family screening. The diagnostic workup includes detection of reduced α-galactosidase A activity in suspected male patients and is confirmed by GLA genetic testing. Women may have normal α-galactosidase A levels (hemizygous carriers), and some experts advocate GLA testing in lieu of enzyme screening. A histologic diagnosis should be suspected by the presence of prominent vacuolization of the cardiac myocytes, and may be confirmed by identification of myelinoid inclusions on electron microscopy. Unfortunately, FD continues to be underdiagnosed because of a combination of variable presentation and unfamiliarity by clinicians.

Noonan syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant disorder with a reported prevalence of approximately 1 in 2500 [38]. The diagnosis is usually made in infancy or childhood, and the clinical findings include distinctive facial features (notably hypertelorism), developmental delay, short stature, renal abnormalities, and congenital heart disease. Pulmonary stenosis with or without a dysplastic pulmonary valve is the most frequent finding; however, cardiac hypertrophy is common (up to 20% of affected individuals) and may be accompanied by dynamic left ventricular obstruction [39].

Conclusion

LVH is a common, albeit nonspecific, manifestation of multiple cardiac disorders. Prompt recognition of the underlying diagnosis has important prognostic and therapeutic implications. Integrating the various, and often subtle, findings on clinical examination and multimodality imaging is essential to distinguishing the different causes, and a methodical approach can help streamline the diagnostic evaluation of these patients.