Introduction

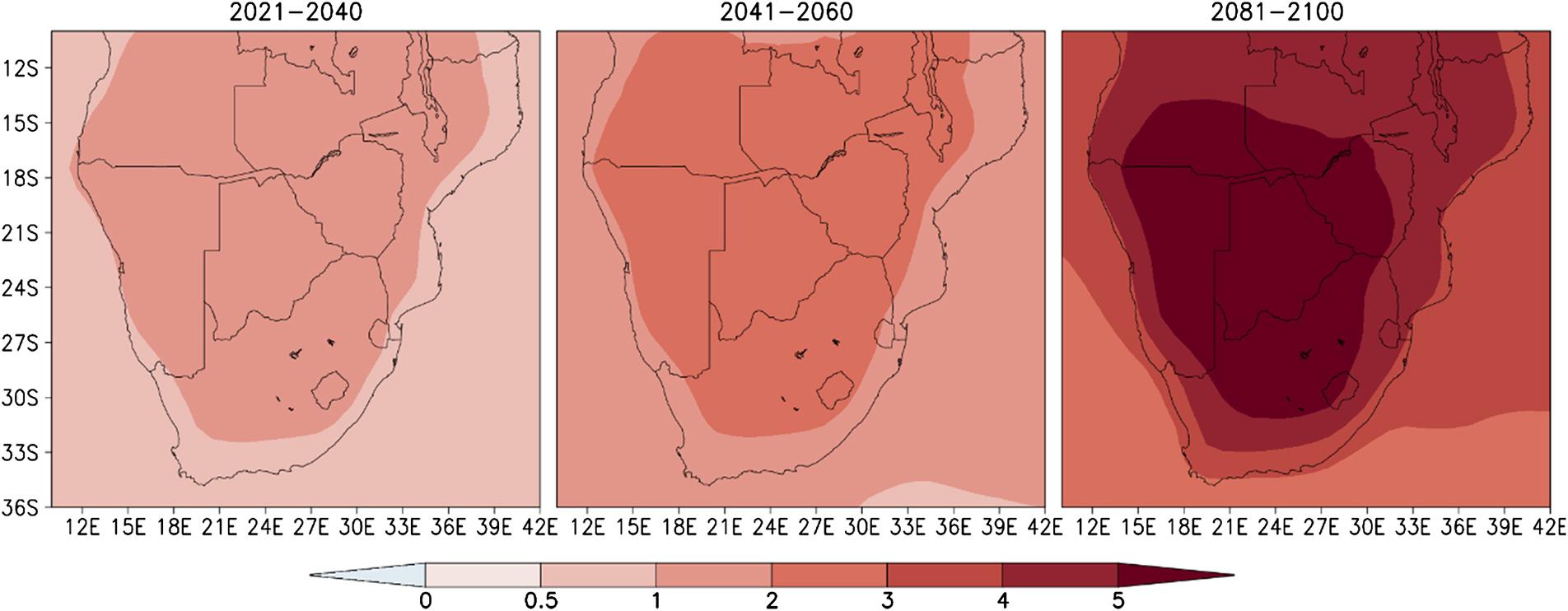

Africa is generally regarded as the continent most vulnerable to climate change, for two reasons. The first relates to the strong climate change signal in Africa, which is impacting on a climate system that is already warm and highly variable, and the second relates to the low adaptive capacity of the region.(1) Southern Africa in particular, has been identified as a climate change hotspot in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C.(2) This region is naturally warm and dry, with highly variable rainfall. Under low mitigation climate change futures, the region is projected to become drastically warmer (Figure 1), and likely also drier, with an even more variable rainfall.(3,4) When warm and dry regions become warmer and drier the options for adaptation are limited, in fact, there may be limits to adaptation.(1)

: Projected change in average annual temperature as per the ensemble average of 30 different Coupled Global Climate Models (CGCMs) that contributed to the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase Six and Assessment Report Six of the IPCC, for the periods 2021-2040 (near-future), 2041-2060 (mid-future) and 2081-2100 (far-futrure), relative to the baseline period 1979-2014, under the low-mitigation scenario SSP5-8.5 (Shared Socio Economic Pathway 5-8.5).

The projected climate change signal described above can already be detected in observations. Temperatures in the interior regions of southern Africa have been rising at about twice the global rate of warming over the last five decades,(3) and negative trends in rainfall have been detected in both the summer and winter rainfall regions.(5) It is also not only average temperatures that are rising, extreme temperature events such as the number of hot days, high fire-danger days and heat waves are already occurring more frequently,(6) and further drastic increases are projected under low-mitigation futures.(3,7)

In the eastern parts of southern Africa, climate change is additionally causing increases in a very different type of risk. Increase in heavy rainfall events and associated flooding can already be observed,(5) and further increases are projected for as long as the climate system continues to warm.(1)

Challenges - Climate change health impacts for the African region

It is against this background that a number of ‘climate impact drivers’, for example floods, droughts and heat waves, already impact on human health in the sub-Saharan region. That is, climate hazards are already adding to a number of health outcomes, and may further aggravate health systems and health in a changing climate. The impacts of recent multi-year droughts in South Africa, namely the 2015-2017 ‘day-zero’ drought in the Western Cape (8) and the current multi-year drought in the Eastern Cape (9) on health are already notable.(10) Due to climate change that has occurred to date, the likelihood of multi-year droughts in the Western Cape is estimated to be about three times greater than it is supposed to be.(11) A formal attribution study has not yet been undertaken for the Eastern Cape drought.

Africa will, among other regions of the world, be impacted by climate change in terms of heat-related mortality.(12) For sub-Saharan Africa, warming is projected to cause the spread of vector borne diseases in areas such as southern and eastern Africa, with risks of malaria and dengue also projected to rise. Additional burden on an already taxed health care system have already emerged because of the Covid pandemic.(12)

Millions of people in southern Africa live exposed to the impacts of climate variability and change, including subsistence farmers who depend on rain fed crops and pastures, and communities that live in informal settlements, where housing cannot usually protect against everyday vagaries of the weather not least for extremes such as heat waves, severe storms and flooding.(13) The impacts of rising temperatures, in particular heat waves and oppressive temperatures impacting on human comfort, health and mortality are a major source of concern.(1,3,14) Already in the next 10 years, heat waves of unprecedented intensity are highly likely to occur in the southern African region, posing life-threatening conditions, particularly for elderly people living in informal housing without easy access to cool water. It is thus imperative that heat-health vulnerabilities in southern Africa are quantified and well understood,(15) so that adaptation options are developed for highly vulnerable groups such as the elderly, pregnant women and outdoor workers.

How do we then intervene across scales to best manage and ‘live’ and adapt to such challenges? Areas where one can make adaptation and other interventions are in the policy and local health arenas.

Opportunities - Climate change policies and guidelines/plans in South Africa

South Africa is a signatory to the 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which aims to address greenhouse gas emissions mitigation and adaptation to climate change, as well as finance support for climate change mitigation and adaptation. In line with the Agreement's requirements, South Africa submitted a Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the UNFCC in 2015, and began a process to update its NDC including public consultation in 2021. The NDC speaks to the mitigation targets that the country is striving towards in light of other key policies and priorities.(16)

In terms of national legislation and policy, the constitution of South Africa section 24 enshrines environmental rights, including the right to an environment that protects human health and well-being. South Africa's highest piece of legislation pertaining to climate change is the Climate Change Bill (Bill Number B9-2022).(17) The bill sets out to enable the development of an effective climate change response to a low-carbon and climate-resilient economy and society for South Africa in the context of sustainable development. The Bill followed numerous stakeholder engagements and research such as the Long-Term Adaptation Scenarios on climate change, and considers both mitigation and adaptation. The Bill places a legal obligation on every organ of state to coordinate and harmonise policies, plans, programmes, strategies and decision-making processes relating to climate change, including the establishment of adaptation objectives for the country that aim to establish specific targets.

Prior to the Climate Change Bill, in 2011, the National Climate Change Response White Paper (18) presented the South African government's vision for an effective climate response and the long-term just transition to a climate-resilient and lower-carbon economy and society. Since then, and in line with the move towards implementing the Climate Change Bill, additional plans were developed. For example, the Integrated Resource Plan (19) (DME, 2019) lays out a pathway for a major shift in electricity policy away from coal towards renewable energy sources. Specific to health, the National Climate Change and Health Adaptation Plan 2014–2019 (20) (NDOH, 2014) provided a board framework for health sector action towards adapting to climate change. A second National Climate Change and Health Adaptation Plan 2020–2024 has also been prepared and is awaiting ministerial signature. More recently, in 2022, South Africa published the National Heat Health Action Guidelines, which is a guide to extreme heat planning in South Africa for the human health sector (21) (NDOH, 2022). The guidelines speak to the need for Heat Health Action Plans, led by the health sector but across all sectors, to prepare and prevent adverse heat-health impacts among communities.

In May 2022, the South African President accepted the Just Transition Framework prepared by the Presidential Climate Commission.(22) The framework is a planning tool that provides actions that government and its social and other partners will take to achieve a just transition, with outcomes planned for the short and long-term. The Intergovernmental Committee on Climate Change will be a key partner in rolling out this framework.

Importantly, climate change guidelines and plans also exist at provincial level such as the Western Cape Climate Change Response Implementation Framework and the Gauteng Overarching Climate Change Research Strategy and Action Plan. Climate change mitigation and adaptation will also be included in the Integrated Development Plans at district and local municipality levels. The ‘Let's Respond’ initiative (23) (DFFE, 2022) by the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment, the South African Local Government Association and the Department of Cooperative Governance is an integrative toolkit for empowering municipalities to integrate climate change risks and opportunities into planning.

Several national databases for climate change exist to assist with monitoring and evaluation of science, activities and policy/guidelines:

- •

South African Risk and Vulnerability Atlas: https://sarva.saeon.ac.za/

- •

South African National Climate Information System. South African Climate Action Tracker: (https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/south-africa/)

- •

A useful guide to South African climate change policy, guidelines and other relevant documents is available online: https://libguides.lib.uct.ac.za/c.php?g=194637& p=1315979.

- •

The National Climate Change Information System: https://ccis.environment.gov.za/#/.

Conclusion

In southern Africa several significant policy decisions such as the second National Climate Change and Health Adaptation Plan, National Heat Health Action Guidelines and the Just Transition Framework have been proposed and discussed at the highest levels of government. The Climate Change Bill was introduced into parliament in February 2022. However, ensuring that actions from the science and various assessments are used and actioned upon on the ‘ground’ remains a challenge. Recent assessments of various health practitioners and their use of climate information to assist in health risk show in some cases that such issues are not central or are not even being actively considered.(24) While practitioners are increasingly becoming aware of climate change and its impact on health, they have indicated that other pressing challenges, such as service delivery are now taking up the central role of various actions. Thus, the system links to integrating climate risk reduction and other governance functions remain a challenge.