- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

The impact of hospital language on the rate of in-hospital harm. A retrospective cohort study of home care recipients in Ontario, Canada

Read this article at

Abstract

Background

Patients who live in minority language situations are generally more likely to experience poor health outcomes, including harmful events. The delivery of healthcare services in a language-concordant environment has been shown to mitigate the risk of poor health outcomes related to chronic disease management in primary care. However, data assessing the impact of language-concordance on the risk of in-hospital harm are lacking. We conducted a population-based study to determine whether admission to a language-discordant hospital is a risk factor for in-hospital harm.

Methods

We used linked administrative health records to establish a retrospective cohort of home care recipients (from 2007 to 2015) who were admitted to a hospital in Eastern or North-Eastern Ontario, Canada. Patient language (obtained from home care assessments) was coded as English (Anglophone group), French (Francophone group), or other (Allophone group); hospital language (English or bilingual) was obtained using language designation status according to the French Language Services Act. We identified in-hospital harmful events using the Hospital Harm Indicator developed by the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

Results

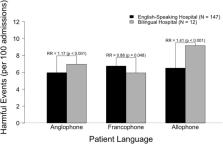

The proportion of hospitalizations with at least 1 harmful event was greater for Allophones (7.63%) than for Anglophones (6.29%, p < 0.001) and Francophones (6.15%, p < 0.001). Overall, Allophones admitted to hospitals required by law to provide services in both French and English ( bilingual hospitals) had the highest rate of harm (9.16%), while Francophones admitted to these same hospitals had the lowest rate of harm (5.93%). In the unadjusted analysis, Francophones were less likely to experience harm in bilingual hospitals than in hospitals that were not required by law to provide services in French ( English-speaking hospitals) (RR = 0.88, p = 0.048); the opposite was true for Anglophones and Allophones, who were more likely to experience harm in bilingual hospitals (RR = 1.17, p < 0.001 and RR = 1.41, p < 0.001, respectively). The risk of harm was not significant in the adjusted analysis.

Related collections

Most cited references20

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Providing High-Quality Care for Limited English Proficient Patients: The Importance of Language Concordance and Interpreter Use

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Language barriers and understanding of hospital discharge instructions.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found