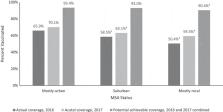

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends that adolescents routinely receive tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap), meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY), and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine ( 1 ) at age 11–12 years. ACIP also recommends catch-up vaccination with hepatitis B vaccine, measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, and varicella vaccine for adolescents who are not up to date with childhood vaccinations. ACIP recommends a booster dose of MenACWY at age 16 years ( 1 ). In December 2016, ACIP updated HPV vaccine recommendations to include a 2-dose schedule for immunocompetent adolescents initiating the vaccination series before their 15th birthday ( 2 ). To estimate adolescent vaccination coverage in the United States, CDC analyzed data from the 2016 National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen) for 20,475 adolescents aged 13–17 years.* During 2015–2016, coverage increased for ≥1 dose of Tdap (from 86.4% to 88.0%) and for each HPV vaccine dose (from 56.1% to 60.4% for ≥1 dose). Among adolescents aged 17 years, coverage with ≥2 doses of MenACWY increased from 33.3% to 39.1%. In 2016, 43.4% of adolescents (49.5% of females; 37.5% of males) were up to date with the HPV vaccination series, applying the updated HPV vaccine recommendations retrospectively. † Coverage with ≥1 HPV vaccine dose varied by metropolitan statistical area (MSA) status and was lowest (50.4%) among adolescents living in non-MSA areas and highest (65.9%) among those living in MSA central cities. § Adolescent vaccination coverage continues to improve overall; however, substantial opportunities exist to further increase HPV-associated cancer prevention. NIS-Teen is an annual survey that collects data on vaccines received by adolescents aged 13–17 years in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, selected local areas, and territories. ¶ NIS-Teen is conducted among parents and guardians of eligible adolescents identified using a random-digit–dialed sample of landline and cellular telephone numbers.** Parents and guardians are interviewed for information on the sociodemographic characteristics of the adolescent and household, and contact information for the child’s vaccination providers. If more than one age-eligible adolescent lives in the household, one adolescent is randomly selected for participation. With parental/guardian consent, health care providers identified during the interview are mailed a questionnaire requesting the vaccination history from the adolescent’s medical record. †† This report presents vaccination coverage estimates for 20,475 adolescents (9,661 females and 10,814 males) aged 13–17 years with adequate provider data. §§ NIS-Teen methodology, including methods for weighting and synthesizing provider-reported vaccination histories, has been described (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/nis/downloads/NIS-PUF15-DUG.pdf). T-tests were used for statistical comparison of weighted data to account for the complex survey design. Weighted linear regression by survey year was used to estimate annual percentage point increases. Differences were considered statistically significant for p-values 10 might not be reliable. § Includes percentages receiving Tdap vaccine at age ≥10 years. ¶ Statistically significant difference (p 10 might not be reliable. ** Includes percentages receiving Tdap vaccine at age ≥10 years. †† Includes percentages receiving MenACWY and meningococcal-unknown type vaccine. §§ Statistically significant difference (p 10 might not be reliable. ¶ ≥1 dose Tdap vaccine at age ≥10 years. ** ≥1 dose of MenACWY or meningococcal-unknown type vaccine. †† HPV vaccine, nine-valent (9vHPV), quadrivalent (4vHPV), or bivalent (2vHPV). For ≥1-, ≥2-, and ≥3-dose measures, percentages are reported among females and males combined (n = 20,475) and for females only (n = 9,661) and males only (n = 10,814). §§ HPV UTD includes those with ≥3 doses, and those with 2 doses when the first HPV vaccine dose was initiated before age 15 years and time between the first and second dose was at least 5 months minus 4 days. ¶¶ Statistically significant (p<0.05) percentage point increase from 2015. *** Statistically significant (p<0.05) percentage point decrease from 2015. ††† Range excludes selected local areas and territories. FIGURE 2 Estimated vaccination coverage* of ≥1 dose of human papillomavirus vaccine † among female adolescents aged 13–17 years § , ¶ —National Immunization Survey–Teen, United States, 2016 Abbreviation: DC = District of Columbia. * National coverage = 65%. † The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends nine-valent, quadrivalent, or bivalent HPV vaccine for females. § Sample size = 9,661. ¶ Includes female adolescents born during January 1998–February 2004. The figure above is a map of the United States showing estimated vaccination coverage of ≥1 dose of human papillomavirus vaccine among female adolescents aged 13–17 years by state during 2016, based on data from the National Immunization Survey–Teen. FIGURE 3 Estimated vaccination coverage* of ≥1 dose of human papillomavirus vaccine † among male adolescents aged 13–17 years § , ¶ — National Immunization Survey–Teen, United States, 2016 Abbreviation: DC = District of Columbia. *National coverage = 56%. † The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends nine-valent or quadrivalent HPV vaccine for males. § Sample size = 10,814. ¶ Includes male adolescents born during January 1998–February 2004. The figure above is a map of the United States showing estimated vaccination coverage of ≥1 dose of human papillomavirus vaccine among male adolescents aged 13–17 years, by state during 2016, based on data from the National Immunization Survey–Teen. Discussion In 2016, adolescent vaccination coverage in the United States was sustained and continued to improve in several areas: compared with 2015, coverage with Tdap, ≥2 doses of varicella vaccine, ≥2 doses of MenACWY, and each dose of HPV vaccine increased. Since HPV vaccine was introduced for females in 2006 and for males in 2011, coverage has increased gradually among females and more rapidly among males. During 2015–2016, increases in coverage with each HPV dose, ranging from 3.4 to 6.2 percentage points occurred among males, whereas only a 2.8 percentage point increase in ≥2-dose HPV coverage occurred among females. Coverage with ≥1-dose HPV vaccine among males continues to approach that among females, particularly for adolescents aged 13 years, suggesting that HPV vaccination of both female and male adolescents has been integrated into vaccination practices. Although HPV vaccination initiation (receipt of ≥1 HPV vaccine dose) continues to increase, coverage remains 22–28 percentage points lower than those for Tdap and ≥1-dose MenACWY. These gaps indicate substantial opportunity for improving HPV vaccination practices. Disparities in adolescent vaccination coverage were found by MSA status: HPV vaccination initiation among adolescents living outside MSA central cities was 16 percentage points lower than among those living in MSA central cities. Although adolescents living in non-MSA areas had substantially lower HPV and MenACWY vaccination coverage compared with those living in MSA central cities, Tdap coverage in these groups was similar. Reasons for these disparities are not well understood. Potential contributing factors might include differences in parental acceptance of certain vaccines and provider participation in, and adolescents’ eligibility for, the Vaccines for Children program.*** The disproportionately lower number of pediatric primary care providers found in non-MSA areas than in MSA central city areas ( 4 , 5 ) might partially explain this difference in vaccination coverage, because nonpediatric providers might be less familiar with adolescent vaccination recommendations. Because Tdap coverage is substantially higher than ≥1-dose HPV coverage, even in non-MSA areas, lack of access to any vaccination services is unlikely the underlying cause of lower HPV vaccine initiation. A better understanding of reasons for variations in HPV vaccine initiation by MSA status is needed to identify appropriate, targeted strategies to improve HPV vaccination coverage. CDC has published a series of reports in an effort to better understand health disparities between rural and urban areas (https://www.cdc.gov/ruralhealth/caseforruralhealth.html). Variation in adolescent vaccination coverage among state and local areas might reflect differences in adolescent health care delivery, the prevalence of factors associated with lower vaccination coverage, and immunization program emphasis on, and effectiveness of, adolescent vaccination activities. Immunization programs in several state and local jurisdictions (e.g., Alaska, Maryland, Nevada, New York, and New York City), although not necessarily having the highest HPV vaccination coverage in the nation, have experienced annual increases in coverage that exceed the national average over a 4-year period. Activities contributing to this success, as reported by these immunization programs, include enhancing provider education, assessing vaccination coverage levels in health care provider offices and providing feedback to the practices, conducting media campaigns, engaging community partners, and experiencing a “spillover” effect from middle school vaccination requirements for Tdap and MenACWY vaccines. At the end of 2016, the recommended HPV vaccination schedule was changed from a 3-dose to a 2-dose series for immunocompetent adolescents initiating the series before their 15th birthday. Three doses are recommended for persons initiating the series at ages 15 through 26 years and for immunocompromised persons ( 2 ). The recommendation allows for 1 fewer dose and one fewer visit to a health care provider, which might encourage providers to promote, and parents to accept, vaccination at the recommended age of 11–12 years. Although it is too early to assess the direct impact of the revised recommendation on vaccination practices, when applied retrospectively, the HPV up-to-date coverage was 6.3 percentage points higher than the ≥3-dose HPV coverage. Each year in the United States, an estimated 31,500 newly diagnosed cancers in men and women are attributable to HPV; approximately 90% of these could be prevented by receipt of the nine-valent HPV vaccine (https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm). Although it is too early to observe the impact of HPV vaccination on HPV-associated cancers, impact on infection with HPV types targeted by the vaccine and other endpoints have been reported ( 6 – 8 ). Data from the 2007–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys indicate that, compared with 2003–2006 (before HPV vaccine introduction), prevalence of HPV types targeted by the quadrivalent HPV vaccine ††† in cervicovaginal specimens had decreased 56% (from 11.5% to 5.0%) among females aged 14–19 years ( 6 ). By 2011–2014, prevalence had declined 71% (from 11.5% to 3.3%) among females aged 14–19 years and 61% (from 18.5% to 7.2%) among females aged 20–24 years ( 7 ). Evidence of vaccine impact among males also exists ( 8 ). The findings in this report are subject to at least five limitations. First, the overall household response rate was 32.7% (55.5% for the landline and 29.5% for the cell phone samples), and only 53.9% of landline-completed and 47.4% of cell phone–completed interviews had adequate provider data. Second, bias in estimates might remain even after adjustment for household and provider nonresponse and phoneless households. ¶¶¶ Weights have been adjusted for the increasing number of cell phone–only households over time. Nonresponse bias might change, which could affect comparisons of estimates between survey years. Third, estimates stratified by state/local area might be unreliable because of small sample sizes. Fourth, multiple statistical tests were conducted, and a small number might be significant because of chance alone. Finally, ≥2-dose MenACWY coverage likely underestimates the proportion of adolescents who receive ≥2 MenACWY doses. Adolescents might receive a booster dose of MenACWY after age 17 years ( 1 ); because NIS-Teen includes adolescents aged 13–17 years, receipt of MenACWY at age ≥18 years cannot be captured in coverage estimates. Adolescent vaccination coverage can be increased, and the gap between HPV vaccination coverage and coverage with Tdap and ≥1-dose MenACWY can be closed with increased implementation of effective strategies. Providers should use every visit to review vaccination histories, provide strong clinical recommendations for HPV and other recommended vaccines, and implement systems to eliminate or minimize missed opportunities (e.g., standing orders, provider reminders, patient reminder or recall, and use of immunization information systems) (https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/vaccination). Resources for clinicians to facilitate effective communication with parents and adolescents regarding HPV and other recommended vaccines are available at https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/index.html. Provider-based performance measurement could also facilitate increased adolescent vaccination coverage, including the Assessment, Feedback, Incentives, and eXchange program implemented by state and local immunization programs with individual providers (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/afix/index.html), and the 2018 updated Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set composite measure for health plans, assessing receipt of Tdap, MenACWY, and HPV vaccines by age 13 years (http://www.ncqa.org/hedis-quality-measurement/hedis-measures/hedis-2018). Protection against vaccine-preventable diseases will be increased if clinicians consistently recommend and simultaneously administer Tdap, MenACWY, and HPV vaccines at age 11–12 years. Summary What is already known about this topic? To protect against vaccine-preventable diseases, including human papillomavirus (HPV)–associated cancers, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, and meningococcal disease, routine immunization of adolescents aged 11–12 years is recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Since HPV vaccine introduction in 2006 for females and 2011 for males, coverage has increased gradually for females and more rapidly for males, although coverage has not reached the tetanus, diphtheria and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) and quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY) coverage. What is added by this report? In December 2016, ACIP updated HPV vaccination recommendations to include a 2-dose schedule for immunocompetent adolescents initiating the vaccine series before their 15th birthday; 3 doses are recommended for persons who initiate the series at age 15–26 years and for immunocompromised persons. A new HPV up-to-date measure was added to the 2016 National Immunization Survey–Teen to account for the revised HPV vaccination schedule. HPV up-to-date estimates were 49.5% for females and 37.5% for males and 6.0–6.5 percentage points higher than ≥3-dose adolescent HPV coverage. HPV up-to-date vaccination coverage was 15 percentage points lower among adolescents living in nonmetropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) than among adolescents living in MSA central cities. What are the implications for public health care? Adolescent vaccination coverage continues to improve, but opportunity remains to increase HPV-associated cancer prevention. A better understanding of reasons for differences in HPV vaccination by MSA status might identify appropriate strategies to improve coverage. Protection against vaccine-preventable diseases will be increased if clinicians consistently recommend and simultaneously administer Tdap, MenACWY, and HPV vaccines at age 11–12 years.