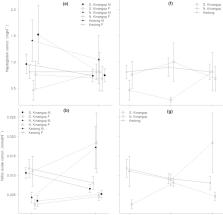

Introduction Influenza A virus, of the family Orthomyxoviridae, carries an RNA genome consisting of eight segments of negative-stranded RNA. This genome encodes one or two non-structural proteins and nine structural proteins, which, together with a host cell–derived lipid envelope, comprise the influenza virus particle. Influenza virus causes widespread morbidity and mortality among human populations worldwide: in the United States alone, an average of 41,400 deaths and 1.68 million hospitalizations [1] are attributed to influenza each year. In temperate regions like the United States, this impact is felt predominantly during the winter months; that is, epidemics recur with a highly predictable seasonal pattern. In northern latitudes, influenza viruses circulate from November to March, while in the southern hemisphere influenza occurs primarily from May to September [2]. Tropical regions, by contrast, experience influenza throughout the year, although increased incidence has been correlated with rainy seasons [2,3]. Despite extensive documentation of the seasonal cycles of influenza and curiosity as to their causes, little concrete data is available to indicate why influenza virus infections peak in the wintertime. Theories to explain the seasonal variation of influenza have therefore proliferated over the years (reviewed in [4]). Current hypotheses include fluctuations in host immune competence mediated by seasonal factors such as melatonin [5] and vitamin D [6] levels; seasonal changes in host behavior, such as school attendance, air travel [7], and indoor crowding during cold or rainy weather; and environmental factors, including temperature [8], relative humidity (RH), and the direction of air movement in the upper atmosphere [9]. In early studies using mouse-adapted strains of influenza virus, experiments performed in the winter months yielded a transmission rate of 58.2%; in contrast, a rate of only 34.1% was observed in the summer months [10]. While these data suggested that the seasonal influences acting on humans also affect laboratory mice, no mechanism to explain the observations was identified. Herein, we directly tested the hypotheses that ambient air temperature and RH impact the efficiency with which influenza virus is spread. As a mammalian animal model we used Hartley strain guinea pigs, which we have recently shown to be highly susceptible to infection with human influenza viruses [11]. Importantly, we also found that naïve guinea pigs readily become infected when exposed to inoculated guinea pigs, unlike mice, which do not efficiently transmit influenza virus [11]. Thus, by housing infected and naïve guinea pigs together in an environmental chamber, we were able to assess the efficiency of transmission under conditions of controlled RH and temperature. Our data show that both RH and temperature do indeed affect the frequency of influenza virus transmission among guinea pigs, although via apparently differing mechanisms. Results Twenty replicate experiments were performed in which all factors remained constant except for the RH and/or temperature inside the environmental chamber. Each experiment involved eight guinea pigs, and transmission under each set of conditions was assessed in duplicate. The arrangement of animals in the environmental chamber is illustrated in Figure 1. Virus contained in nasal wash samples collected on alternating days post-inoculation (p.i.) was titrated by plaque assay to determine the infection status of each animal. Serum samples were collected from each animal prior to infection and on day 17 p.i., and seroconversion was assessed by hemagglutination inhibition assay (results in Table S1). Figure 1 Arrangement of Infected and Exposed Guinea Pigs in Environmental Chamber In each experiment, eight animals were housed in a Caron 6030 environmental chamber. Each guinea pig was placed in its own cage, and two cages were positioned on each shelf. Naïve animals were placed behind infected animals, such that the direction of airflow was toward the naïve animals. The cages used were open to airflow through the top and one side, both of which were covered by wire mesh. Although infected and exposed guinea pigs were placed in pairs, air flowed freely between shelves, allowing transmission to occur from any infected to any naïve animal. In general, the behavior (level of activity, food and water consumption, symptoms of infection) of guinea pigs was not observed to change with the ambient relative humidity. Likewise, animals housed at 5 °C behaved in a similar manner to those housed at 20 °C. Guinea pigs kept at 30 °C consumed more water than those housed under cooler conditions, and appeared lethargic. Consistent with our previous observations [11], influenza virus–infected guinea pigs did not display detectable symptoms of disease (e.g., weight loss, fever, sneezing, coughing) during the experiments described. Transmission Efficiency Is Dependent on Relative Humidity The results of transmission experiments performed at 20 °C and five different RHs (20%, 35%, 50%, 65%, and 80%) indicated that the efficiency of aerosol spread of influenza virus varied with RH. Transmission was highly efficient (occurred to three or four of four exposed guinea pigs) at low RH values of 20% or 35%. At an intermediate RH of 50%, however, only one of four naïve animals contracted infection. Three of four exposed guinea pigs were infected at 65% RH, while no transmission was observed at a high RH of 80% (Figure 2). Where transmission was observed, the kinetics with which infection was detected in each exposed animal varied between and within experiments. To an extent, we believe this variation is due to the stochastic nature of infection. However, while most infection events were the product of primary transmission from an inoculated animal, others could be the result of secondary transmission from a previously infected, exposed guinea pig. With the exception of the lack of transmission at 80% RH, the observed relationship between transmission and RH is similar to that between influenza virus stability in an aerosol and RH [12], suggesting that at 20 °C the sensitivity of transmission to humidity is due largely to virus stability. Figure 2 Transmission of Influenza Virus from Guinea Pig to Guinea Pig Is Dependent on Relative Humidity Titers of influenza virus in nasal wash samples are plotted as a function of day p.i. Overall transmission rate and the RH and temperature conditions of each experiment are stated underneath the graph. Titers from intranasally inoculated guinea pigs are represented as dashed lines; titers from exposed guinea pigs are shown with solid lines. Virus titrations were performed by plaque assay on Madin Darby canine kidney cells. Transmission Efficiency Is Inversely Correlated with Temperature To test whether cold temperatures would increase transmission, the ambient temperature in the chamber was lowered to 5 °C and experiments were performed at 35%–80% RH. Overall, transmission was more efficient at 5 °C: 75%–100% transmission occurred at 35% and 50% RH, and 50% transmission was observed at 65% and 80% RH (Figure 3A–3H). The statistical significance of differences in transmission rates at 5 °C compared to 20 °C was assessed using the Fisher's exact test. While at 35% and 65% RH the difference was not found to be significant, at both 50% and 80% RH, transmissibility at 5 °C was found to be greater than that at 20 °C (p 20 °C) and either intermediate (50%) or high (80%) RHs. Materials and Methods Virus. Influenza A/Panama/2007/99 virus (Pan/99; H3N2) was kindly supplied by Adolfo García-Sastre and was propagated in Madin Darby canine kidney cells. Animals. Female Hartley strain guinea pigs weighing 300–350 g were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. Animals were allowed free access to food and water and kept on a 12-h light/dark cycle. Guinea pigs were anesthetized for the collection of blood and of nasal wash samples, using a mixture of ketamine (30 mg/kg) and xylazine (2 mg/kg), administered intramuscularly. All procedures were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Used Committee guidelines. During guinea pig transmission experiments, strict measures were followed to prevent aberrant cross-contamination between cages: sentinel animals were handled before inoculated animals, gloves were changed between cages, and work surfaces were sanitized between guinea pigs. Transmission experiments. The term “aerosol” is used herein to describe respiratory droplets of all sizes. The term “droplet nuclei” is used to refer to droplets that remain airborne (typically less than 5 μm in diameter). Each transmission experiment involved eight guinea pigs. On day 0, four of the eight guinea pigs were inoculated intranasally with 103 PFU of influenza A/Panama/2007/99 virus (150 μl per nostril in phosphate buffered saline [PBS] supplemented with 0.3% bovine serum albumin [BSA]) and housed in a separate room from the remaining animals. At 24 h p.i., each of the eight guinea pigs was placed in a “transmission cage”, a standard rat cage (Ancare R20 series) with an open wire top, which has been modified by replacing one side panel with a wire grid. The transmission cages were then placed into the environmental chamber (Caron model 6030) with two cages per shelf, such that the wire grids opposed each other (Figure 1). In this arrangement, the guinea pigs cannot come into physical contact with each other. Each infected animal was paired on a shelf with a naïve animal. The guinea pigs were housed in this way for 7 d, after which they were removed from the chamber and separated. On day 2 p.i. (day 1 post-exposure) and every second day thereafter up to day 12 p.i., nasal wash samples were collected from anesthetized guinea pigs by instilling 1 ml of PBS-BSA into the nostrils and collecting the wash in a Petri dish. Titers in nasal wash samples were determined by plaque assay of 10-fold serial dilutions on Madin Darby canine kidney cells. Serum samples were collected from each animal prior to infection and on day 17 post-infection, and seroconversion was assessed by hemagglutination inhibition assay. All transmission experiments reported herein were performed between September 2006 and April 2007. Analysis of expression levels of mediators of innate immunity. Guinea pigs were inoculated with 103 PFU of Pan/99 virus intranasally and immediately housed under the appropriate conditions (5 °C or 20 °C and 35% RH). At days 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7 post-infection, three guinea pigs were killed and their nasal turbinates removed. Tissues were placed immediately in RNAlater reagent (Qiagen), and stored at 4 °C for 1 to 5 d. RNA was extracted from equivalent masses of tissue using the RNAeasy Protect Mini kit (Qiagen) and subjected to DNAse treatment (Qiagen). One microgram of RNA was subjected to reverse transcription using MMLV reverse transcriptase (Roche). One microlitre of the resultant product was used as the template in a SYBR green (Invitrogen) real-time PCR assay (Roche Light Cycler 480) with Ampli-taq Gold polymerase (Perkin-Elmer). Primers used were as follows: β-actin f AAACTGGAACGGTGAAGGTG; β-actin r CTTCCTCTGTGGAGGAGTGG; Mx1 f CATCCCYTTGrTCATCCAGT; Mx1 r CATCCCyTTGRTCATCCAGT; MDA-5 f GAGCCAGAGCTGATGARAGC; MDA-5 r TCTTATGWGCATACTCCTCTGG; IL-1β f GAAGAAGAGCCCATCGTCTG; IL-1β r CATGGGTCAGACAACACCAG; RANTES f GCAATGCTAGCAGCTTCTCC; RANTES r TTGCCTTGAAAGATGTGCTG; TLR3 f TAACCACGCACTCTGTTTGC; TLR3 r ACAGTATTGCGGGATCCAAG; TNFα f TTCCGGGCAGATCTACTTTG; TNFα r TGAACCAGGAGAAGGTGAGG; MCP-1 f ATTGCCAAACTGGACCAGAG; MCP-1 r CTACGGTTCTTGGGGTCTTG; MCP-3 f TCATTGCAGTCCTTCTGTGC; MCP-3 r TAGTCTCTGCACCCGAATCC; IFNγ f GACCTGAGCAAGACCCTGAG; IFNγ r TGGCTCAGAATGCAGAGATG; STAT1 f AAGGGGCCATCACATTCAC; STAT1 r GCTTCCTTTGGCCTGGAG; TBK1 f CAAGAAACTyTGCCwCAGAAA; TBK1 r AGGCCACCATCCAykGTTA; IRF5 f CAAACCCCGaGAGAAGAAG; IRF5 r CTGCTGGGACtGCCAGA; IRF7 f TGCAAGGTGTACTGGGAGGT; IRF7 r TCACCAGGATCAGGGTCTTC (where R = A or G, Y = C or T, W = A or T, K = T or G). Primer sequences were based either on guinea pig mRNA sequences available in GenBank (MCP1, MCP3, IL-1b, IFNγ, RANTES, TLR3, TNFα, and β-actin), or on the consensus sequence of all species available in GenBank (Mx1, MDA-5, IRF5, IRF7, STAT1, and TBK1). Sequencing of each PCR product indicated that all primer pairs were specific for the expected transcript. Reactions were performed in duplicate and normalized by dividing the mean value of the cycle threshold (Ct) of β-actin expressed as an exponent of 2 (2Ct) by the mean value of 2Ct for the target gene. The fold-induction over the mock-infected was then calculated by dividing the normalized value by the normalized mock value. Data is represented in Figure 5 as the mean of three like samples (nasal turbinates harvested on the same day p.i. from three guinea pigs) ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software. Supporting Information Table S1 Seroconversion of Inoculated and Exposed Guinea Pigs Results of hemagglutination inhibition tests for each transmission experiment are shown. (58 KB DOC) Click here for additional data file. Accession Numbers The GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/index.html) accession numbers of guinea pig genes used for primer design are as follows: β-actin (AF508792.1); IFNγ (AY151287.1); IL-1β (AF119622); MCP-1 (L04985); MCP-3 (AB014340); RANTES (CPU77037); TLR3 (DQ415679.1); and TNFα (CPU77036).