- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Vaccination Coverage with Selected Vaccines and Exemption Rates Among Children in Kindergarten — United States, 2018–19 School Year

research-article

Ranee Seither , MPH

1

,

,

Caitlin Loretan , MPH

1

,

2 ,

Kendra Driver , MSc

1

,

3 ,

Jenelle L. Mellerson , MPH

1

,

4 ,

Cynthia L. Knighton

1 ,

Carla L. Black , PhD

1

18 October 2019

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

State and local school vaccination requirements exist to ensure that students are

protected against vaccine-preventable diseases (

1

). This report summarizes data collected by state and local immunization programs*

on vaccination coverage among children in kindergarten in 49 states, exemptions for

kindergartners in 50 states, and provisional enrollment and grace period status for

kindergartners in 30 states. Nationally, vaccination coverage

†

was 94.9% for the state-required number of doses of diphtheria and tetanus toxoids,

and acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP); 94.7% for 2 doses of measles, mumps, and rubella

vaccine (MMR); and 94.8% for the state-required doses of varicella vaccine. Whereas

2.5% of kindergartners had an exemption from at least one vaccine,

§

2.8% of kindergartners were not up to date for MMR and did not have a vaccine exemption.

Nearly all states could achieve the recommended ≥95% MMR coverage if all nonexempt

kindergartners were vaccinated in accordance with local and state vaccination policies.

In accordance with state and local school entry requirements, parents and guardians

submit children’s vaccination records or exemption forms to schools, or schools obtain

records from state immunization information systems. Federally funded immunization

programs collaborate with departments of education, school nurses, and other school

personnel to assess vaccination coverage and exemption status of children enrolled

in public and private kindergartens and to report unweighted counts, aggregated by

school type, to CDC via a web-based questionnaire in the Secure Access Management

System.

¶

CDC uses these counts to produce state-level and national-level estimates of vaccination

coverage. During the 2018–19 school year, 49 states reported coverage for all state-required

vaccines among public school kindergartners; 48 states reported on private school

kindergartners.** All 50 states reported exemption data among public school kindergartners;

49 states reported on private school kindergartners. Overall national and median vaccination

coverage for the state-required number of doses of DTaP, MMR, and varicella vaccine

are reported. Coverage with hepatitis B and poliovirus vaccines, which are required

in most states but not included in this report, are available at SchoolVaxView (

2

). Thirty states reported data on kindergartners who, at the time of assessment, attended

school under a grace period (attendance without proof of complete vaccination or exemption

during a set interval) or provisional enrollment (school attendance while completing

a catch-up vaccination schedule). Coverage and exemptions from the U.S. territories

and affiliated jurisdictions are included in this report; however, national estimates,

medians, and summary measures include only U.S. states.

Vaccination coverage and exemption estimates were adjusted according to survey type

and response rates.

††

For the 2018–19 school year, CDC is reporting national-level estimates alongside the

state-level median estimates. The national estimates complement the medians by addressing

the limitation that the median estimates weight every state equally regardless of

population size. Reported estimates for the 2018–19 school year are based on 3,634,896

kindergartners surveyed for vaccination coverage, 3,643,598 for exemptions, and 2,813,482

for grace period and provisional enrollment among the 4,001,404 children reported

as enrolled in kindergarten by the 50 state immunization programs.

§§

Potentially achievable coverage with MMR, defined as the sum of the percentage of

children up to date with 2 doses of MMR and those with no documented vaccination exemption

but not up date, was calculated for each state. Nonexempt students include those provisionally

enrolled, in a grace period, or otherwise without documentation of vaccination. SAS

(version 9.4; SAS Institute) was used for all analyses.

Vaccination assessments varied by immunization program because of differences in states’

required vaccines and doses, vaccines assessed, methods, and data reported (Supplementary

Table 1, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/81811). Most states reported kindergartners

as up to date for a given vaccine if they had received all doses of that vaccine required

for school entry,

¶¶

except seven states*** that reported kindergartners as up to date for any given vaccine

only if they had received all doses of all vaccines required for school entry.

Nationally, 2-dose MMR coverage was 94.7% (range = 87.4% [Colorado] to ≥99.2% [Mississippi]).

Coverage of ≥95% was reported by 20 states and coverage of <90% by two (Table). DTaP

coverage was 94.9% (range = 88.8% [Idaho] to ≥99.2% [Mississippi]). Coverage of ≥95%

was reported by 21 states, and coverage of <90% by one. Varicella vaccine coverage

was 94.8% (range=86.5% [Colorado] to ≥99.2% [Mississippi]), with 20 states reporting

coverage ≥95%, and four reporting <90% coverage.

TABLE

Estimated* vaccination coverage

†

for measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine (MMR), diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and

acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP), and varicella vaccine, grace period or provisional

enrollment,

§

and any exemption

¶

among children enrolled in kindergarten, by immunization program — United States,

territories, and associated states, 2018–19 school year

Immunization program

Kindergarten population**

No. (%) surveyed††

MMR,

2 doses (%)§§

DTaP,

5 doses (%)¶¶

Varicella, 2 doses (%)***

Grace period or provisional enrollment (%)

Any exemption (%)

Percentage point change in any exemption from 2017 to 2018

National estimate†††

4,001,404

3,634,896

94.7

94.9

94.8

2.0

2.5

0.2

Median†††

Not applicable

Not applicable

94.2

94.6

94.3

1.8

2.6

0.4

State

Alabama§§§,¶¶¶

77,739

77,739 (100.0)

≥90.6

≥90.6

≥90.6

NP

0.8

−0.1

Alaska¶¶¶,****

10,316

8,702 (84.4)

NR

NR

NR

NR

7.1

0.1

Arizona§§§,††††

79,981

79,981 (100.0)

92.9

92.7

95.6

NR

6.0

0.2

Arkansas§§§§

39,257

37,466 (95.4)

94.2

93.4

93.8

4.5

1.8

0.1

California¶¶¶,††††,§§§§

568,947

555,735 (97.7)

96.5

96.0

97.9

1.7

0.6

−0.1

Colorado§§§,¶¶¶¶

64,191

64,191 (100.0)

87.4

90.3

86.5

0.6

4.9

0.2

Connecticut§§§,¶¶¶

38,230

38,230 (100.0)

95.9

96.1

95.7

NP

2.7

0.4

Delaware¶¶¶

10,798

1,021 (9.5)

97.8

97.8

97.6

NR

1.2

−0.2

District of Columbia****

NA

NA

NR

NR

NR

NR

NR

NA

Florida§§§,¶¶¶,*****

224,641

224,641 (100.0)

≥93.8

≥93.8

≥93.8

2.9

3.2

0.3

Georgia§§§,¶¶¶

131,275

131,275 (100.0)

≥93.6

≥93.6

≥93.6

0.2

2.5

−0.2

Hawaii¶¶¶

16,051

1,081 (6.6)

91.5

92.4

94.0

1.3

4.4

1.3

Idaho

22,995

22,769 (99.0)

89.5

88.8

88.3

2.2

7.7

0.6

Illinois§§§,¶¶¶¶

143,876

143,876 (100.0)

94.7

94.7

94.4

1.1

1.8

0.2

Indiana¶¶¶

82,324

79,350 (96.4)

91.2

94.4

93.5

NR

1.3

0.4

Iowa§§§,¶¶¶

40,624

40,624 (100.0)

≥93.3

≥93.3

≥93.3

3.0

2.4

0.4

Kansas¶¶¶,§§§§,†††††

37,838

8,744 (23.1)

90.8

91.0

89.2

NR

2.1

0.4

Kentucky¶¶¶,§§§§,*****

55,587

55,024 (99.0)

93.4

94.1

92.8

NR

1.4

0.0

Louisiana§§§

56,203

56,203 (100.0)

95.5

97.7

95.4

NA

1.2

0.1

Maine

13,419

12,875 (95.9)

93.8

94.5

95.9

NR

6.2

0.9

Maryland¶¶¶,§§§§

71,431

71,423 (100.0)

97.4

97.7

97.1

NR

1.5

0.1

Massachusetts§§§,¶¶¶,§§§§

65,279

65,279 (100.0)

96.9

97.1

96.5

NP

1.4

0.1

Michigan§§§

118,632

118,632 (100.0)

94.6

94.8

94.3

0.6

4.5

0.3

Minnesota¶¶¶¶,*****

70,085

68,779 (98.1)

92.6

92.5

92.0

NR

3.7

0.2

Mississippi§§§,¶¶¶,††††

37,775

37,775 (100.0)

≥99.2

≥99.2

≥99.2

0.6

0.1

0.0

Missouri§§§,¶¶¶¶

72,687

72,687 (100.0)

94.8

94.8

94.5

NR

2.7

0.4

Montana§§§,¶¶¶

12,480

12,480 (100.0)

93.3

93.0

92.9

1.9

4.5

0.2

Nebraska¶¶¶,§§§§,

26,925

26,548 (98.6)

96.9

97.4

96.3

1.3

2.1

−0.1

Nevada¶¶¶

37,971

1,811 (4.8)

95.1

95.0

94.7

1.0

3.3

0.1

New Hampshire¶¶¶

12,421

12,421 (100.0)

≥91.8

≥91.8

≥91.8

4.9

3.3

0.4

New Jersey§§§,¶¶¶

109,161

109,161 (100.0)

≥95.0

≥95.0

≥95.0

1.1

2.5

0.3

New Mexico¶¶¶

25,269

25,170 (99.6)

96.1

96.0

95.7

1.9

1.5

−0.2

New York (including New York City)§§§,¶¶¶

220,495

220,495 (100.0)

97.2

96.7

96.7

1.9

1.3

0.2

New York City§§§,¶¶¶

96,912

96,912 (100.0)

97.7

97.0

97.1

1.2

0.7

0.0

North Carolina¶¶¶,§§§§,*****

124,343

113,074 (90.9)

93.2

93.2

93.1

1.6

1.6

−0.4

North Dakota

10,382

10,315 (99.4)

93.6

93.6

93.8

NR

4.3

0.9

Ohio

139,679

132,589 (94.9)

91.6

91.9

91.2

6.7

2.9

0.3

Oklahoma*****

54,806

50,456 (92.1)

92.2

92.7

95.8

NR

2.6

0.4

Oregon§§§, §§§§

45,870

45,870 (100.0)

93.0

92.4

94.3

NR

7.7

0.1

Pennsylvania

143,560

133,945 (93.3)

96.4

96.6

95.8

2.6

2.9

0.1

Rhode Island§§§,¶¶¶,§§§§,*****

10,964

10,964 (100.0)

97.4

97.4

97.0

NR

1.3

0.2

South Carolina¶¶¶

58,442

15,797 (27.0)

94.2

94.6

93.5

0.9

2.6

0.6

South Dakota¶¶¶

12,062

12,052 (99.9)

96.2

95.8

95.5

NR

2.6

0.4

Tennessee§§§,¶¶¶,§§§§

78,630

78,630 (100.0)

96.5

96.2

96.2

1.6

1.9

0.4

Texas (including Houston)§§§§,*****

390,034

387,530 (99.4)

96.9

96.7

96.5

1.5

2.4

0.4

Houston§§§§,*****

37,897

37,675 (99.4)

96.6

96.6

95.9

1.4

1.5

0.3

Utah§§§

50,179

50,179 (100.0)

92.8

92.4

92.5

2.3

5.7

0.4

Vermont§§§,¶¶¶

6,126

6,126 (100.0)

93.0

92.9

92.3

5.1

4.7

0.9

Virginia¶¶¶,†††††

100,394

4,422 (4.4)

95.0

98.0

93.6

NR

1.7

0.2

Washington*****

87,510

84,771 (96.9)

90.8

90.8

89.7

1.7

5.0

0.3

West Virginia¶¶¶,††††,§§§§§

19,442

15,426 (79.3)

98.8

98.7

98.5

2.3

0.8

0.6

Wisconsin§§§§,*****,†††††

66,344

1,530 (2.3)

92.6

96.2

91.6

4.9

5.9

0.5

Wyoming

7,734

7,734 (100.0)

95.1

95.3

94.7

2.5

2.9

NA

Territories and associated states

American Samoa¶¶¶

NA

NA

NA

NA

NReq

NP

NA

NA

Federated States of Micronesia§§§

1,786

1,786 (100.0)

91.3

80.2

NReq

NR

0.0

0.0

Guam¶¶¶

2,563

735 (28.7)

88.4

90.7

NReq

NR

0.1

-0.3

Marshall Islands§§§,¶¶¶,††††

1,114

1,114 (100.0)

95.1

83.8

NReq

NR

0.0

0.0

Northern Mariana Islands§§§

812

812 (100.0)

97.7

79.4

98.2

NR

0.0

0.0

Palau§§§,¶¶¶¶¶

304

304 (100.0)

100.0

100.0

NReq

NR

0.0

0.0

Puerto Rico

26,353

1,545 (5.9)

94.7

91.4

94.7

NR

1.6

NA

U.S. Virgin Islands

NA

NA

NA

NA

NA

NA

NA

NA

Abbreviations: NA = not available; NP = no grace period/provisional policy; NR = not

reported to CDC; NReq = not required.

* Estimates are adjusted for nonresponse and weighted for sampling where indicated.

† Estimates based on a completed vaccine series (i.e., not vaccine-specific) use the

“≥” symbol. Coverage might include history of disease or laboratory evidence of immunity.

§ A grace period is a set number of days during which a student can be enrolled and

attend school without proof of complete vaccination or exemption. Provisional enrollment

allows a student without complete vaccination or exemption to attend school while

completing a catch-up vaccination schedule. In states with one or both of these policies,

the estimates represent the number of kindergartners within a grace period, provisionally

enrolled, or some combination of these categories.

¶ Exemptions, grace period, provisional enrollment, and vaccine coverage status might

not be mutually exclusive. Some children enrolled under a grace period or provisional

enrollment might be exempt from one or more vaccinations, while children with exemptions

might be fully vaccinated with one or more required vaccines.

** The kindergarten population is an approximation provided by each program. The national

total excludes the 8,075 kindergartners from the District of Columbia for which data

were not reported.

†† The number surveyed represents the number of kindergartners surveyed for vaccination

coverage. For Alaska, this number represents the number surveyed for exemptions because

coverage was not reported. The national total excludes the 8,702 kindergartners from

Alaska. Exemption estimates are based on 31,792 kindergartners for Kansas, 95,875

kindergartners for Virginia, and 66,652 kindergartners for Wisconsin.

§§ Most states require 2 doses of MMR; Alaska, New Jersey, and Oregon require 2 doses

of measles, 1 dose of mumps, and 1 dose of rubella vaccines. Georgia, New York, New

York City, North Carolina, and Virginia require 2 doses of measles and mumps, 1 dose

of rubella vaccines. Iowa requires 2 doses of measles and 2 doses of rubella vaccines.

¶¶ Pertussis vaccination coverage might include some diphtheria, tetanus toxoids,

and pertussis vaccine (DTP) vaccinations if administered in another country or by

a vaccination provider who continued to use DTP after 2000. Most states require 5

doses of DTaP for school entry, or 4 doses if the 4th dose was received on or after

the 4th birthday; Illinois, Maryland, Virginia, and Wisconsin require 4 doses; Nebraska

requires 3 doses. The reported coverage estimates represent the percentage of kindergartners

with the state-required number of DTaP doses, except for Kentucky, which requires

≥5 doses but reports ≥4 doses of DTaP.

*** Most states require 2 doses of varicella vaccine for school entry; Alabama, Arizona,

California, Hawaii, Maine, New Jersey, Oklahoma, and Oregon require 1 dose. Reporting

of varicella vaccination status for kindergartners with a history of varicella disease

varied within and among states; some were reported as vaccinated against varicella

and others as medically exempt.

††† National coverage estimates and medians calculated from data from 49 states (i.e.,

does not include Alaska). National grace period or provisional enrollment estimate

and median were calculated from data from 30 states that have either a grace period

or provisional enrollment policy and reported relevant data to CDC. National exemption

estimate and median were calculated from data from 50 states. Other jurisdictions

excluded were Houston, Texas, New York City, American Samoa, Guam, Marshall Islands,

Federated States of Micronesia, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Puerto Rico, and

U.S. Virgin Islands. Data reported from 3,634,896 kindergartners assessed for coverage,

3,643,598 for exemptions and 2,813,482 for grace period/provisional enrollment. Estimates

represent rates for populations of 3,991,088; 4,001,404; and 3,025,009 kindergartners

for coverage, exemptions and grace period/provisional enrollment, respectively.

§§§ The proportion surveyed likely was <100% but is reported as 100% based on incomplete

information about the actual current enrollment.

¶¶¶ Philosophical exemptions were not allowed.

**** Kindergarten vaccination coverage (Alaska and District of Columbia) and exemption

data (District of Columbia) were not reported because of problems with data collection.

†††† Religious exemptions were not allowed.

§§§§ Counted some or all vaccine doses received regardless of Advisory Committee on

Immunization Practices recommended age and time interval; vaccination coverage rates

reported might be higher than those for valid doses.

¶¶¶¶ Program did not report the number of children with exemptions, but instead reported

the number of exemptions for each vaccine, which could count some children more than

once. Lower bounds of the percentage of children with any exemptions were estimated

using the individual vaccines with the highest number of exemptions.

***** Did not include some types of schools, such as online schools or those located

on military bases, in correctional facilities, or on tribal lands.

††††† Kindergarten vaccination coverage data were collected from a sample, and exemption

data were collected from a census of kindergartners.

§§§§§ Reported public school data only.

¶¶¶¶¶ For Palau, estimates represent coverage among children in first grade.

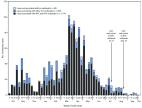

The percentage of kindergartners with an exemption from one or more required vaccines

(not limited to MMR, DTaP, and varicella vaccines) was 2.5% in 2018–19 (range = 0.1%

[Mississippi] to 7.7% [Idaho and Oregon]). This is slightly higher than the 2.3% during

the 2017–18 school year and 2.1% in 2016–17. (Table) (Figure 1). Nationally, 0.3%

of kindergartners had a medical exemption, and 2.2% had a nonmedical exemption (Supplementary

Table 2, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/81810).

FIGURE 1

Estimated national percentage exempt and range of states’ exemptions from one or more

vaccines among kindergartners — United States, 2013–14 to 2018–19 school years

The figure is a line chart showing estimated national percentage exempt and range

of states’ exemptions from one or more vaccines among kindergartners in the United

States during the 2013–14 to 2018–19 school years.

The percentage of kindergartners attending school within a grace period or provisionally

enrolled among the 30 states reporting these data was 2.0% (range = 0.2% [Georgia]

to 6.7% [Ohio]) (Table). In 10 of these states, the percentage of children provisionally

enrolled or within a grace period at the time of assessment exceeded the percentage

of children with exemptions from one or more vaccines. Forty-four states could potentially

achieve ≥95% MMR coverage if all nonexempt kindergartners, many of whom are within

a grace period or provisionally enrolled, were vaccinated (Figure 2). Follow-up could

assure all missing vaccinations are completed and all missing documentation of vaccination

is provided to schools.

FIGURE 2

Potentially achievable coverage*

,†,§ with measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine (MMR) among kindergartners — 49 states,

2018–2019 school year

* Potentially achievable coverage is estimated as the sum of the percentage of students

with up-to-date MMR and the percentage of students without up-to-date MMR and without

a vaccine exemption.

† The exemptions used to calculate the potential increase in MMR coverage for Arizona,

Arkansas, Colorado, Idaho, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri,

Nebraska, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island,

Texas, Utah, Vermont, and Wyoming are the number of children with exemptions specifically

for MMR vaccine. For all other states, numbers are based on an exemption to any vaccine.

§ Alaska and the District of Columbia did not report kindergarten vaccination coverage

for the 2018–19 school year and are excluded from this analysis.

The figure is a stacked bar chart showing potentially achievable coverage with measles,

mumps, and rubella vaccine among kindergartners in 49 states during the 2018–2019

school year.

Discussion

Measles outbreaks affecting school-age children across multiple states during the

2018–19 school year underscore the importance of both school vaccination requirements

for preventing disease spread and school coverage assessments to identify pockets

of undervaccination (

3

). During the 2018–19 school year, national coverage with MMR, DTaP, and varicella

vaccines remained near 95% (

2

,

4

). However, coverage and exemption rates varied by state. Recent measles outbreaks

in states with high overall MMR coverage, such as New York, highlight the need for

assessing vaccination coverage at the local level. CDC encourages programs to use

their local-level school assessment data to identify populations of undervaccinated

students and to partner with schools and providers to reduce barriers to vaccination

and improve coverage.

Although the overall percentage of children with an exemption increased slightly for

the second consecutive school year, children with exemptions still represent a small

proportion of kindergartners nationally and in most states. More importantly, in 25

states, the number of nonexempt undervaccinated kindergartners exceeded the number

of those with exemptions. In many states, nonexempt undervaccinated students are attending

school in a grace period or are provisionally enrolled. Fifteen states allow grace

periods, with 30 days the most common length, and 47 states allow provisional enrollment

for students in the process of completing the vaccination schedule (R McCord, CDC,

unpublished data, 2019). Follow-up with parents of these students to verify that vaccinations

and related documentation are complete typically falls to school nurses or other school

staff members (R Seither, CDC, unpublished data, 2019). The California Department

of Public Health’s immunization program collaborated with the state Department of

Education and with individual schools to reduce provisional enrollment substantially

over several years, which resulted in measurable increases in vaccination coverage,

through training on the correct application of the relevant rules so that only those

children who were completing a catch-up schedule were provisionally enrolled, and

audits to assess the implementation by school staff members (

5

,

6

). Almost all states could achieve ≥95% MMR coverage if undervaccinated nonexempt

children were vaccinated in accordance with local and state vaccination policies.

The findings in this report are subject to at least five limitations. First, comparability

is limited because of variation in states’ requirements, data collection methods,

and definitions of grace period and provisional enrollment. Second, representativeness

might be negatively affected because of data collection methods that miss some schools

or students, such as homeschooled students, or assess vaccination status at different

times. Third, actual vaccination coverage, exemption rates, or both might be underestimated

or overestimated because of inaccurate or absent documentation or missing schools.

Fourth, national coverage estimates include only 49 of 50 states, exemption estimates

include all states but use lower-bound estimates for four states, and grace period

or provisional enrollment estimates include only 30 states for the 2018–19 school

year. Finally, because most states do not report vaccine-specific exemptions, estimates

of potentially achievable MMR coverage are approximations. However, if reported exemptions

were for a vaccine or vaccines other than MMR, potentially achievable MMR coverage

would be higher than that presented.

Kindergarten vaccination requirements help ensure that students are fully vaccinated

with recommended vaccines upon school entry. CDC works with immunization programs

to collect and report data on school vaccination coverage, exemption rates, and grace

period and provisional enrollment each year. Immunization programs can use these data

to identify schools and communities with high concentrations of undervaccinated students

and inform strategies to increase vaccination coverage. Such strategies include education

campaigns to counteract misinformation in areas with high numbers of vaccine exemptions

and increased follow-up of undervaccinated students without exemptions to ensure these

children are vaccinated in accordance with local and state vaccination policies (

7

) to reduce the risk for transmission of vaccine-preventable diseases.

Summary

What is already known about this topic?

State immunization programs conduct annual kindergarten vaccination assessments to

monitor school-entry vaccination coverage with all state-required vaccines.

What is added by this report?

For the 2018–19 school year, coverage was 94.7% for 2 doses of measles, mumps, and

rubella vaccine (MMR) and 94.9% for the state-required number of doses of diphtheria

and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine, and 94.8% for varicella vaccine.

Although the exemption rate slightly increased to 2.5%, most states could achieve

the recommended ≥95% MMR coverage if undervaccinated children without an exemption

were completely vaccinated.

What are the implications for public health practice?

State and local immunization programs can use school coverage assessments to detect

pockets of undervaccination and guide strategies to increase vaccination coverage.

Related collections

Most cited references3

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

National Update on Measles Cases and Outbreaks — United States, January 1–October 1, 2019

Manisha M. Patel, Adria D. Lee, Nakia Clemmons … (2019)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Associations of Statewide Legislative and Administrative Interventions With Vaccination Status Among Kindergartners in California

S. Pingali, Paul Delamater, Alison Buttenheim … (2019)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Clinical Inquiries: Which interventions are effective in managing parental vaccine refusal?

Dan Brelsford, Elise Knutzen, Jon Neher … (2017)