- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Canadian Airway Focus Group updated consensus-based recommendations for management of the difficult airway: part 1. Difficult airway management encountered in an unconscious patient Translated title: Mise à jour des lignes directrices consensuelles pour la prise en charge des voies aériennes difficiles du Canadian Airway Focus Group: 1 ère partie. Prise en charge de voies aériennes difficiles chez un patient inconscient

Read this article at

Abstract

Purpose

Since the last Canadian Airway Focus Group (CAFG) guidelines were published in 2013, the literature on airway management has expanded substantially. The CAFG therefore re-convened to examine this literature and update practice recommendations. This first of two articles addresses difficulty encountered with airway management in an unconscious patient.

Source

Canadian Airway Focus Group members, including anesthesia, emergency medicine, and critical care physicians, were assigned topics to search. Searches were run in the Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and CINAHL databases. Results were presented to the group and discussed during video conferences every two weeks from April 2018 to July 2020. These CAFG recommendations are based on the best available published evidence. Where high-quality evidence was lacking, statements are based on group consensus.

Findings and key recommendations

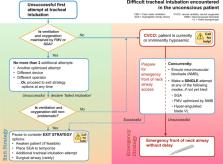

Most studies comparing video laryngoscopy (VL) with direct laryngoscopy indicate a higher first attempt and overall success rate with VL, and lower complication rates. Thus, resources allowing, the CAFG now recommends use of VL with appropriately selected blade type to facilitate all tracheal intubations. If a first attempt at tracheal intubation or supraglottic airway (SGA) placement is unsuccessful, further attempts can be made as long as patient ventilation and oxygenation is maintained. Nevertheless, total attempts should be limited (to three or fewer) before declaring failure and pausing to consider “exit strategy” options. For failed intubation, exit strategy options in the still-oxygenated patient include awakening (if feasible), temporizing with an SGA, a single further attempt at tracheal intubation using a different technique, or front-of-neck airway access (FONA). Failure of tracheal intubation, face-mask ventilation, and SGA ventilation together with current or imminent hypoxemia defines a “cannot ventilate, cannot oxygenate” emergency. Neuromuscular blockade should be confirmed or established, and a single final attempt at face-mask ventilation, SGA placement, or tracheal intubation with hyper-angulated blade VL can be made, if it had not already been attempted. If ventilation remains impossible, emergency FONA should occur without delay using a scalpel-bougie-tube technique (in the adult patient). The CAFG recommends all institutions designate an individual as “airway lead” to help institute difficult airway protocols, ensure adequate training and equipment, and help with airway-related quality reviews.

Résumé

Depuis la dernière publication des lignes directrices du Canadian Airway Focus Group (CAFG) en 2013, la littérature sur la prise en charge des voies aériennes s’est considérablement étoffée. Le CAFG s’est donc réuni à nouveau pour examiner la littérature et mettre à jour ses recommandations de pratique. Ce premier article de deux traite de la prise en charge des voies aériennes difficiles chez un patient inconscient.

Des sujets de recherche ont été assignés aux membres du Canadian Airway Focus Group, qui compte des médecins anesthésistes, urgentologues et intensivistes. Les recherches ont été menées dans les bases de données Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials et CINAHL. Les résultats ont été présentés au groupe et discutés lors de vidéoconférences toutes les deux semaines entre avril 2018 et juillet 2020. Les recommandations du CAFG sont fondées sur les meilleures données probantes publiées. Si les données probantes de haute qualité manquaient, les énoncés se fondent alors sur le consensus du groupe.

La plupart des études comparant la vidéolaryngoscopie à la laryngoscopie directe indiquent un taux de réussite plus élevé à la première tentative et globalement avec la vidéolaryngoscopie, ainsi que des taux de complication inférieurs. Ainsi, les ressources le permettant, le CAFG recommande dorénavant l’utilisation de vidéolaryngoscopes avec le type de lame convenablement sélectionné pour faciliter toutes les intubations trachéales. En cas d’échec de la première tentative d’intubation trachéale ou d’échec de positionnement du dispositif supraglottique (DSG), d’autres tentatives peuvent être entreprises tant que la ventilation et l’oxygénation du patient le permettent. Néanmoins, le nombre total de tentatives devrait être limité, à trois ou moins, avant de déclarer un échec et de considérer les options de « stratégie de retrait ». En cas d’échec de l’intubation, les options de stratégie de retrait chez un patient toujours oxygéné comprennent l’éveil (si possible), la temporisation avec un DSG, une dernière tentative d’intubation trachéale à l’aide d’une technique différente, ou une cricothyroïdotomie. L’échec de l’intubation trachéale, de la ventilation au masque facial et de la ventilation via un DSG accompagné d’une hypoxémie présente ou imminente, définit une urgence « impossible de ventiler, impossible d’oxygéner ». Le bloc neuromusculaire doit alors être confirmé ou mis en place, et une tentative finale de ventilation au masque, de positionnement du DSG ou d’intubation trachéale avec une lame de vidéolaryngoscopie hyper-angulée peut être réalisée, si cette approche n’a pas encore été essayée. Si la ventilation demeure impossible, une cricothyroïdotomie d’urgence devrait être réalisée sans délai utilisant une technique de scalpel-bougie-tube (chez le patient adulte). Le CAFG recommande à toutes les institutions de désigner une personne comme « leader des voies aériennes » afin d’assister à la mise en place de protocoles pour les voies aériennes difficiles, d’assurer une formation et un équipement adéquats et d’aider aux examens de la qualité en rapport avec les voies aériennes.

Related collections

Most cited references304

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults†

- Record: found

- Abstract: not found

- Article: not found