- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Where Does Human Plague Still Persist in Latin America?

Read this article at

Abstract

Background

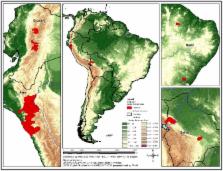

Plague is an epidemic-prone disease with a potential impact on public health, international trade, and tourism. It may emerge and re-emerge after decades of epidemiological silence. Today, in Latin America, human cases and foci are present in Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, and Peru.

Aims

The objective of this study is to identify where cases of human plague still persist in Latin America and map areas that may be at risk for emergence or re-emergence. This analysis will provide evidence-based information for countries to prioritize areas for intervention.

Methods

Evidence of the presence of plague was demonstrated using existing official information from WHO, PAHO, and Ministries of Health. A geo-referenced database was created to map the historical presence of plague by country between the first registered case in 1899 and 2012. Areas where plague still persists were mapped at the second level of the political/administrative divisions (counties). Selected demographic, socioeconomic, and environmental variables were described.

Results

Plague was found to be present for one or more years in 14 out of 25 countries in Latin America (1899–2012). Foci persisted in six countries, two of which have no report of current cases. There is evidence that human cases of plague still persist in 18 counties. Demographic and poverty patterns were observed in 11/18 counties. Four types of biomes are most commonly found. 12/18 have an average altitude higher than 1,300 meters above sea level.

Discussion

Even though human plague cases are very localized, the risk is present, and unexpected outbreaks could occur. Countries need to make the final push to eliminate plague as a public health problem for the Americas. A further disaggregated risk evaluation is recommended, including identification of foci and possible interactions among areas where plague could emerge or re-emerge. A closer geographical approach and environmental characterization are suggested.

Author Summary

Plague is a disease of epidemic potential that could emerge and re-emerge after decades of epidemiological silence. Today, in Latin America, human cases and natural foci are present in Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, and Peru. We searched for official information of where cases of human plague still persist in Latin America, mapped the areas, and briefly described selected factors. This analysis will provide evidence-based information for countries to prioritize areas for intervention. A geo-referenced database and risk map were created. One or more events of plague were found in 14 of 25 countries in Latin America in the period of 1899–2012. There is evidence that human cases of plague still persist in 18 of the almost 13,300 second levels of the political/administrative divisions (counties). Demographic and poverty patterns were observed in 11/18 counties. Four types of biomes are most commonly found and 12/18 counties have an average altitude higher than 1,300 meters above sea level. Even though human plague cases are very localized, the risk is still present, and unexpected outbreaks could occur. Countries need to make the final push to eliminate plague as a public health problem for the Americas. A further disaggregated risk evaluation and a closer environmental characterization are recommended.

Related collections

Most cited references23

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Climate and vectorborne diseases.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Plague: Past, Present, and Future

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found