- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

IMI – Defining and Classifying Myopia: A Proposed Set of Standards for Clinical and Epidemiologic Studies

Abstract

Purpose

We provide a standardized set of terminology, definitions, and thresholds of myopia and its main ocular complications.

Methods

Critical review of current terminology and choice of myopia thresholds was done to ensure that the proposed standards are appropriate for clinical research purposes, relevant to the underlying biology of myopia, acceptable to researchers in the field, and useful for developing health policy.

Results

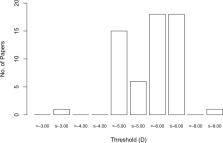

We recommend that the many descriptive terms of myopia be consolidated into the following descriptive categories: myopia, secondary myopia, axial myopia, and refractive myopia. To provide a framework for research into myopia prevention, the condition of “pre-myopia” is defined. As a quantitative trait, we recommend that myopia be divided into myopia (i.e., all myopia), low myopia, and high myopia. The current consensus threshold value for myopia is a spherical equivalent refractive error ≤ −0.50 diopters (D), but this carries significant risks of classification bias. The current consensus threshold value for high myopia is a spherical equivalent refractive error ≤ −6.00 D. “Pathologic myopia” is proposed as the categorical term for the adverse, structural complications of myopia. A clinical classification is proposed to encompass the scope of such structural complications.

Related collections

Most cited references33

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Effect of Time Spent Outdoors at School on the Development of Myopia Among Children in China: A Randomized Clinical Trial.

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found