- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Case Study: Remission of Type 2 Diabetes After Outpatient Basal Insulin Therapy

research-article

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

Diabetes is a chronic, progressive disease with potentially serious sequelae. Treatment

for type 2 diabetes often begins with oral agents and eventually requires insulin

therapy. As the disease progresses, drug therapies are often intensified and rarely

reduced to control glycemia. Conversely, in type 1 diabetes, some patients experience

a “honeymoon period” shortly after diagnosis, wherein insulin needs decrease significantly

before intensification is needed (1). No comparable honeymoon period has been widely

described for type 2 diabetes. However, a few studies have demonstrated that drug-free

glycemic control can be achieved in type 2 diabetes for 12 months on average after

a 2-week continuous insulin infusion (2–4). Here, we describe an unusual case of a

26-month drug holiday induced with outpatient basal insulin in a patient newly diagnosed

with type 2 diabetes.

Case Presentation

A 69-year-old white woman (weight 72.7 kg, height 59 inches, BMI 32.3 kg/m2) was diagnosed

with type 2 diabetes in June 2011. She presented with an A1C of 17.6% (target <7%)

and a fasting blood glucose (FBG) of 452 mg/dL (target 70–130 mg/dL). Before diagnosis,

the patient had not used any oral or parenteral steroids nor had she experienced any

traumatic physical or emotional event or illness that could have abruptly increased

her blood glucose. Metformin 500 mg twice daily was initiated at diagnosis, but was

discontinued 9 days later to avoid risk of lactic acidosis, as her serum creatinine

was 1.5 mg/dL. At that time, her fasting self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) values

ranged from 185 to 337 mg/dL. Treatment with 25 units of insulin detemir daily (0.34

units/kg/day) was initiated in place of metformin. The patient was counseled on diet

modifications and encouraged to exercise.

One month later (July 2011), the patient’s fasting SMBG values had improved to a range

of 71–212 mg/dL with a single hypoglycemic episode (58 mg/dL); her weight and BMI

increased slightly to 74.1 kg and 32.9 kg/m2, respectively. Hypoglycemia education

was reinforced, and insulin therapy was switched from 25 units of detemir delivered

with the Levemir FlexPen to 28 units (0.38 units/kg/day) of insulin glargine delivered

with the Lantus SoloStar due to the patient’s preference for this device. Two weeks

later, the patient reported continued improvements in fasting SMBG (70–175 mg/dL)

with one hypoglycemic episode (67 mg/dL). In response to the hypoglycemic episode,

her insulin glargine dose was decreased to 25 units daily.

In September, the patient reported fasting SMBG values ranging between 71 and 149

mg/dL, and her A1C was 7.9%. On days when the patient skipped lunch, her midday blood

glucose level would drop to <70 mg/dL (54–60 mg/dL). She was counseled not to skip

meals, and her insulin glargine dose was maintained.

In October, the patient’s weight was 71.4 kg, and her BMI was 31.7 kg/m2. She reported

recently initiating a cinnamon supplement and switching her beverage intake from sugar-sweetened

products to water and diet soda. Although the majority of her fasting SMBG values

were controlled (80–110 mg/dL), she had experienced six hypoglycemic episodes (FBG

13–64 mg/dL). All values were objectively confirmed in the patient’s glucose meter,

and the meter was replaced in case of device error. Her daily insulin glargine dose

was decreased to 20 units (0.28 units/kg/day).

In December, her SMBG values ranged between 70 and 106 mg/dL preprandially and 111

and 207 mg/dL postprandially, and she had had six additional hypoglycemic episodes

(42–66 mg/dL). The patient’s weight remained stable at 71.4 kg (BMI 31.7 kg/m2). At

this follow-up visit, her daily insulin glargine dose was decreased further to 15

units (0.21 units/kg/day).

The patient self-discontinued daily insulin glargine in March 2012 but continued using

the cinnamon supplements. She continued to perform SMBG 1–3 times/day, anticipating

loss of glycemic control. During the next 2 years, her A1C remained stable (from 6.3%

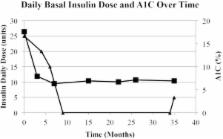

in January 2012 to 6.9% in May 2014) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Daily basal insulin dose and A1C over time. Black triangle = insulin units; black

square = A1C.

At a follow-up visit in May 2014, the patient’s SMBG indicated a need for resumed

drug therapy (FBG 107–169 mg/dL, postprandial blood glucose 108–328 mg/dL). Her weight

at this time was 65.5 kg (BMI 29.1 kg/m2). Insulin glargine was reinitiated at 5 units

daily (0.08 units/kg/day).

During the drug-free period of March 2012 to May 2014, the patient maintained her

lack of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption. However, she reported having difficulties

purchasing healthy food options because of financial constraints. In August 2013,

she was specifically encouraged to incorporate physical activity (walking) into her

daily routine. The patient’s weight during the drug-free interval declined from 70

kg in March 2012 to 65.5 kg in May 2014.

Discussion

Hyperglycemia causes pancreatic β-cell toxicity, leading to decreased insulin release

(3). In type 1 diabetes, the honeymoon period occurs when residual pancreatic β-cell

function is partially restored for an average of 7.2 months, as hyperglycemic stress

is removed before the β-cells are ultimately destroyed (1,3).

Past studies demonstrated induction of a drug-free period when patients newly diagnosed

with type 2 diabetes were treated with 2–3 weeks of intensive insulin therapy (2–5).

Ilkova et al. (2) induced a 12-month drug-free period in 46.2% (n = 6) of patients

using an insulin infusion averaging 0.61 units/kg/day. Three patients maintained glycemic

control for 37–59 months. Li et al. (3) also induced a 12-month drug-free period in

47.1% (n = 32) of patients with an insulin infusion of 0.7 units/kg. Additional studies

indicate that basal-bolus insulin therapy (0.37–0.74 units/kg/day) using NPH and regular

insulin can also induce a 12-month drug-free period in a similar percentage of patients

(43.8–44.9%) (4,5).

The mechanism of remission appears to be related to resumption of endogenous insulin

production after glucotoxicity is resolved. Glucotoxicity has been shown to inhibit

first-phase insulin secretion from the pancreatic β-cells (3). Li et al. (3) theorized

that an insulin infusion corrects hyperglycemia and removes stress from the β-cells,

allowing them to produce insulin, resulting in euglycemia. Their study quantified

an increase in secretion of endogenous insulin (44%) and C-peptide (26%) after 2 weeks

of continuous insulin infusion. The mechanism through which insulin induces a period

of drug-free glycemic control in type 2 diabetes appears to be similar to that causing

the honeymoon period in type 1 diabetes.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of basal insulin monotherapy–induced remission

of type 2 diabetes. Previous studies required multiple daily injections in a basal-bolus

therapy regimen using NPH and regular insulin or hospitalization of patients administered

a continuous insulin infusion (2–5).

Basal-only insulin therapy may be a slower method of achieving remission compared

to more intensive insulin regimens. In this case, basal insulin was maintained for

9 months. However, according to the FBG trend, discontinuation could have occurred

sooner. This report suggests that a trial of basal insulin dosed at 0.2–0.3 units/kg/day,

with follow-up every 2–4 weeks in severely hyperglycemic patients with newly diagnosed

type 2 diabetes, may be an alternative method to achieving temporary remission. Although

this insulin regimen requires a longer timeframe compared to remission induced by

basal-bolus therapy or continuous insulin infusion, it provides a more convenient

outpatient therapeutic option at a lower cost.

Limitations of this case study include the patient’s use of cinnamon supplementation,

which was continued throughout the drug-free period. Although reports are conflicting

regarding its efficacy in type 2 diabetes, it is possible that cinnamon may have exerted

a mild antidiabetic effect. Positive cinnamon studies have demonstrated a 0.36% A1C

reduction after 3 months of use (6). Additionally, the patient’s weight declined by

3.75% during the 9 months of basal insulin therapy, which was likely in response to

introducing dietary modifications related to beverage consumption. Most studies suggest

that an A1C reduction of 0.36% (7) to 0.66% (8) can be achieved with intensive lifestyle

interventions. Therefore, it is unlikely that cinnamon in combination with the mild

lifestyle modifications accounted for a nearly 11% A1C reduction from baseline.

Eliminating the consumption of sugar-rich beverages alters the postprandial glycemic

curve. In clinical practice, suppressing postprandial blood glucose excursions by

adopting significant dietary improvements may postpone or obviate the need for bolus

insulin therapy. Likewise, the remission of diabetes potentially may be achieved,

as seen in this case, with monotherapy basal insulin when dietary modifications significantly

alter the postprandial glycemic curve. However, it is unknown whether remission can

be achieved using basal insulin administration alone in patients who choose not to

incorporate lifestyle modifications or in patients with baseline healthy eating and

exercise habits.

Although weight changes did not appear to contribute to disease remission, the moderate

weight loss (6.5%) achieved during the drug-free interval and continued SMBG both

may have contributed to maintaining and extending the remission period. The Diabetes

Prevention Program (9) showed that lifestyle modifications aimed at achieving a 7%

reduction of weight significantly delay the onset of diabetes compared to placebo

and metformin. Finally, performing SMBG through the drug-free period may have empowered

the patient by providing objective criteria necessary to validate the benefits of

lifestyle modifications.

Based on this case, it is possible that initial type 2 diabetes management with basal

insulin can temporarily restore β-cell function to a degree to which blood glucose

control can be maintained without drug therapy. Although previous studies conducted

with intensive insulin regimens have reported response rates nearing 50% for ∼12 months

(2–5), future studies should investigate the ideal basal dose, percentage of patient

responders, duration of drug-free glycemic control, and mechanism through which this

phenomenon occurs. This case further highlights the need to educate every newly diagnosed

patient about the treatment of hypoglycemic events.

Summary

The purposeful remission of diabetes is not widely attempted or generally considered

possible. Although literature exists regarding the temporary honeymoon period experienced

after insulin initiation in some people with type 1 diabetes (1), comparatively little

research is available regarding the influence of insulin on the remission of type

2 diabetes. Current literature suggests benefit in nearly 50% of patients newly diagnosed

with type 2 diabetes using one of the following strategies: a 2-week inpatient insulin

infusion or multiple daily injections of basal-bolus therapy (2–5). However, there

are disadvantages to these methods. A continuous insulin infusion requires inpatient

admission, whereas a basal-bolus insulin regimen requires purchase of two products

and administration of multiple subcutaneous injections daily. Unfortunately, both

methods may be impractical, costly, and inconvenient for many patients newly diagnosed

with type 2 diabetes.

This case outlines a third potential option for inducing remission of type 2 diabetes:

basal insulin monotherapy. Using this approach avoids the costly and inconvenient

hospital admission required for the continuous insulin infusion strategy. Furthermore,

the cost of drug therapy is reduced with the purchase of one rather than two insulin

products, as needed in a basal-bolus insulin regimen. Additionally, using basal insulin

alone reduces the risk of hypoglycemic events that may occur with stacking of multiple

insulin products. Finally, requiring only one injection of insulin each day offers

a more manageable alternative for newly diagnosed patients compared to the multiple

daily injections required with a basal-bolus insulin regimen.

By using this basal insulin strategy, the patient in this case was able to achieve

drug-free glycemic control for 26 months. Early initiation of basal insulin monotherapy

in patients newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes is a more convenient and cost-effective

approach than methods previously described and could potentially induce remission

of type 2 diabetes in other patients.

Related collections

Most cited references5

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Effect of intensive insulin therapy on beta-cell function and glycaemic control in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a multicentre randomised parallel-group trial.

Jianping Weng, Yanbing Li, Wen Xu … (2008)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Induction of long-term glycemic control in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients is associated with improvement of beta-cell function.

Bin Yao, Wen Xu, Yanbing Li … (2004)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: not found

Glycated haemoglobin and blood pressure-lowering effect of cinnamon in multi-ethnic Type 2 diabetic patients in the UK: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial.

R Akilen, A Tsiami, D Devendra … (2010)