Introduction

The post-apartheid South African state’s attempts to channel investments seem to have been based on the rhetoric of building a developmental state framework akin to the Japanese, Taiwanese and South Korean developmental experiences (ANC 1990a, 1990b, 1991, 2005; Fine 2010; Turok 2005). The African National Congress (ANC) as a ruling party seeks to build a developmental state capable of directing private sector investment towards industrial growth. The automotive industry, which is globally integrated, has been one of the priority sectors that the post-apartheid government has identified to promote (DTI 2003a, 2003b). However, the perennial problem for all government elites under capitalism – including South Africa’s of course – is how to attract and channel investment in private ownership (Block 1987). This problem has been exacerbated by the increased global mobility of capital. That the power of capital has increased over labour and states is not denied in the debates on globalisation (Ó Riain 2000). What is at stake, though, is the impact of globalisation on the scope of the state’s action in carrying out national development in the current global economy. Part of this debate revolves around whether nation-states can still steer investment towards industrial growth in the context of globalisation, which has increased the power of capital against the state and labour.

The Motor Industry Development Programme (MIDP) has been hailed as a ‘success story’ of post-apartheid industrial policy and it is also suggested as a good example of a post-apartheid developmental industrial policy (Barnes, Kaplinsky, and Morris 2003). This article uses the automobile industrial policy to show that the post-apartheid state’s efforts to attract and retain investment in the automobile industry have not been akin to those of a developmental state. However, these efforts are akin to a business nanny state as opposed to a developmental state. The developmental states determine – of course within the partnership and consent of a self-interested business class – where, when and how much to invest. The South African state, however, through the MIDP, has only managed to influence how much can be produced in, and exported from, South Africa.

This article does not only contribute towards the literature on the obstacles to building developmental states in the Global South in the era of neoliberal globalisation, but also addresses gaps in the South African developmental state literature, which has a limited focus in that it tends to be prescriptive about the institutional and macroeconomic policies required to construct a developmental state (Edigheji 2010). The literature argues that South Africa has no developmental state because it has failed to build appropriate institutional capacity to discipline business. In paying too much attention to prescribing the institutional conditions necessary for the emergence of a developmental state, the literature fails to analyse the attempts of the state to direct investment, ostensibly along the lines of a developmental state. More importantly, the South African literature ignores the actual power relations between business and the state that are necessary for the emergence of a developmental state, thus ignoring the structural class power of business.

The literature that focuses on business also has its limitations. It only shows how the state facilitated the outward investment of South African capital, thereby disabling the state from mobilising capital to diversify the South African industrial structure (Fine 2010; Mohamed 2010). This is based on an implicit counterfactual logic that tighter capital controls could have locked investable capital in South Africa, thus generating financial conditions for a developmental state. This view is based on an erroneous assumption that the local bourgeoisie is inherently interested in the installation of a developmental state; it argues that the South African state just needs the political will and state capacity to discipline business through macroeconomic policy manipulation. The Indian state’s attempts to install a developmental state beginning in the 1950s and continuing to the early 1970s, which were successfully opposed by Indian industrial business, make this assumption untenable (Chibber 2003).

The South African literature on the developmental state ignores the structural power of business over ownership and control of investment decisions, which enables business to influence state building. In this article, I argue that indeed, the scope of state action in undertaking national development strategies has been circumscribed by World Trade Organization (WTO) measures on investment, trade and intellectual property rights – also known as trade-related investment measures (TRIMS) (Wade 2003). However, the nation-states are not powerless in the process of capitalist trade and investment expansion. Nation-states are institutional conduits through which the freedom of business is exercised (Meiksins-Wood 2003). Neoliberalism has been used as the ideology to promote more freedom for business in investment decisions and appropriating more profit, through liberalisation of trade, labour and financial markets, and lowering of taxation and expenditure on poor people’s social welfare (Harvey 2007). What the neoliberal ideology obscures is the enormous fiscal support which states provide to business, yet it berates welfare support for the poor in the name of fiscal discipline. Borrowing from Baker’s concept of a business nanny state (Baker 2006), the case of the South African motor industrial policy shows, contrary to the neoliberal perspective, that the state intervenes to distribute income in favour of the rich. In the government financial year 2015–16, the South African government spent more than R23 billion in cash grants, duty credits and rebates for the automotive industry (National Treasury 2017, 127–130).

In this article, I also contend that, contrary to the institutionalist arguments in the South African literature, the absence of the developmental state in South Africa cannot be fully explained by the post-apartheid state’s institutional deficiencies. To understand the absence of a developmental state, we have to take seriously the power of business, interests and strategy of business, and in this instance, the power of South Africa-based automotive multinational companies. These automobile manufacturers are mainly interested in low production costs offered by state largesse in the MIDP incentives which have not increased employment; instead, they have increased profits for the automotive industry.

The article is organised as follows. The first part lays out the rationale behind the introduction of the MIDP, how it works and its economic impact. The second part explains why the state elite failed to install a developmental state. Lastly, the article sums up the main arguments.

Logic and economic impact of the South African automobile industrial policy

As mentioned earlier, the South African state’s attempts to build a developmental state through its automobile industrial policy take place in the context of more internationalised production and there are also high levels of inter-business competition for higher returns and inter-state competition to attract investment. Therefore, if the state is to attract and channel investments, it requires different capacities from the developmental states that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s. Table 1 shows that between 1970 and 2010 there has been an increase in auto investment in the Global South, mainly in China, India and the countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Before 1989, automobile production was mainly located in the Global North. Automobile manufacturing started in Europe and the United States in the late nineteenth century, and grew worldwide through foreign direct investment, licensing and exporting.

| Growth of automobile production in major countries | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 1960 | 1989 | 2000 | 2010 | ||||

| Production (000 units) | World share (%) | Production (000 units) | World share (%) | Production (000 units) | World share (%) | Production (000 units) | World share (%) | |

| France | 1175 | 10 | 3409 | 10 | 2784 | 7 | 2227 | 3 |

| Germany | 1817 | 15 | 4564 | 14 | 5309 | 14 | 5905 | 9 |

| Italy | 596 | 5 | 1972 | 6 | 1410 | 4 | 838 | 1 |

| Spain | 43 | 0 | 1639 | 5 | 2208 | 6 | 2387 | 3 |

| Sweden | 108 | 1 | 384 | 1 | 385 | 1 | 217 | 0 |

| UK | 1353 | 11 | 1299 | 4 | 1786 | 5 | 1393 | 2 |

| Canada | 323 | 3 | 984 | 3 | 1626 | 4 | 2071 | 3 |

| USA | 6675 | 54 | 6823 | 21 | 5636 | 14 | 7761 | 11 |

| Japan | 165 | 1 | 9052 | 27 | 8100 | 21 | 9625 | 14 |

| Korea | NA | NA | 872 | 3 | 2361 | 6 | 4271 | 6 |

| Malaysia | NA | NA | 94 | 0 | 266 | 1 | 567 | 1 |

| Taiwan | NA | NA | NA | NA | 245 | 1 | 303 | 0 |

| Argentina | 30 | 0 | 112 | 0 | 225 | 1 | 716 | 1 |

| Brazil | 38 | 0 | 731 | 2 | 1103 | 3 | 3648 | 5 |

| Mexico | 28 | 0 | 439 | 1 | 994 | 3 | 2345 | 3 |

| Australia | NA | NA | 357 | 1 | 334 | 1 | 243 | 0 |

| Czech Republic | NA | NA | 184 | 1 | 475 | 1 | 1076 | 2 |

| Poland | NA | NA | 289 | 1 | 573 | 1 | 869 | 1 |

| China | 22 | 0 | 580 | 2 | 2000 | 5 | 18,264 | 27 |

| India | 47 | 0 | 2033 | 6 | 801 | 2 | 3536 | 5 |

| South Africa | 87 | 1 | 220 | 1 | 357 | 1 | 472 | 1 |

| World | 12,351 | 100 | 33,204 | 100 | 38,978 | 100 | 68,734 | 100 |

NA: data not available.

Sources: OICA (http://www.oica.net/), ACMA (1991–92).

Table 1 also shows that in 1960 seven advanced developed countries including Japan and others located in North America and Western Europe accounted for almost 90% of the world’s automotive production. In 1960 the United States, led by the largest automotive companies, Ford and General Motors, constituted the largest share of automotive investment and provided 54% of the world’s automotive output. Europe’s response to the worldwide dominance of American car manufacturers was to impose high tariffs for imports, resulting in US auto companies establishing plants in European nation-states to sidestep tariff barriers (Kesavatana 1989). Ford’s, General Motors’ and Chrysler’s dominance of world automobile production was usurped by the rise of Japanese auto companies in the 1970s and 1980s. Table 1 shows that the contribution of the United States to world automobile production decreased from 54% in 1960 to 20% in 1989, while Japan’s contribution increased from 1% in 1960 to 23% in 1989 owing to better access to the US markets.

As in many countries, investment in and expansion of the automobile industry in South Africa since the inception of the industry in the 1920s were achieved through an import substitution industrialisation (ISI) programme, which included a 100% protective tariff regime and other forms of subsidies (Barnes 2013). In exchange for subsidies and the protection of the domestic market, auto companies were required since the 1950s to increase the percentage of locally manufactured components fitted to locally built vehicles. The protection of the domestic market and subsidies to automotive firms served as economic incentives, which led to an increase in the number of companies establishing assembly plants in South Africa from the 1950s to the early 1980s. Between the 1970s and mid 1990s there were low levels of automotive investment and production output, which was a reflection of falling profitability in the manufacturing sector, including the automotive industry. In 1994, South Africa-based automotive vehicle manufacturers produced 39 vehicle models for a small market of less than 300,000 (Black 2007). The automobile industry under apartheid had been characterised by low levels of investment, labour productivity, profits and domestic demand associated with the small size of the South African market, worsened by the disproportionate proliferation of a higher number of models (Barnes, Kaplinsky, and Morris 2003).

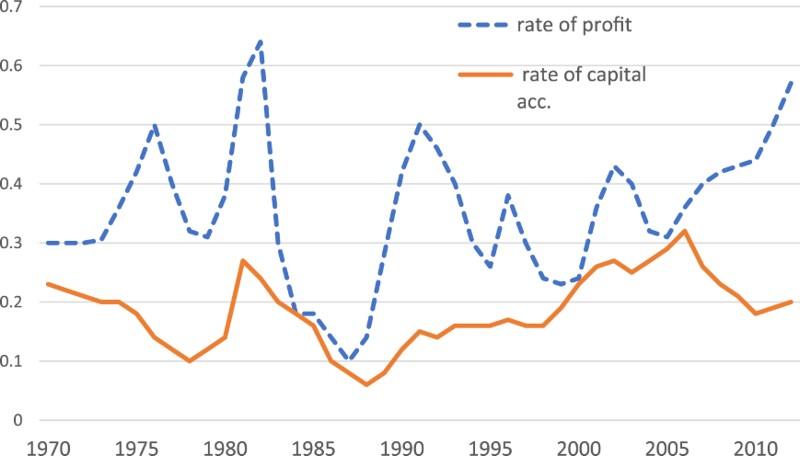

The crisis of profitability in the mid 1970s and 1980s as shown in Figure 4 manifested itself in the high levels of retrenchments of workers, linked in part to the mechanisation of the labour process. Alec Erwin, the then National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) policy strategist who later became the Minister of Trade and Industry in the post-apartheid government, points out that ‘there was continual battle against retrenchments in the industry. It was clear that we had to do something’ (Interview 1, Alec Erwin, 2013).1 In 1992 NUMSA, through the National Economic Forum, persuaded the then Minister of Trade and Industry, Derek Keys, to establish a Motor Industry Task Group (MITG) to look at possible solutions to the crisis in the automotive industry (Ibid.). Indeed, in 1992 Keys appointed a Task Team composed of organised labour, the automotive business and government to recommend how to increase automotive production and make it globally competitive while maintaining employment. The negotiations on industrial policy focused on whether to continue with the ISI initiated in 1925 or to foster international competition in the domestic market through trade liberalisation and export promotion (Hirsch 2005). Labour engaged itself in what Adler and Webster (1999) called ‘bargained liberalization’ to negotiate with business and the state to mitigate the negative effects of economic liberalisation.

A year after its election to government, the ANC signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which committed South Africa to trade liberalisation. For South Africa, this meant the automotive industry had to reduce its tariff from 115% in 1993 to 40% by 2002, but the government chose to lower the tariffs below WTO bound rates. The signing of GATT marked a decisive break with the ISI strategy. Whilst some amounts of protection are still allowed, the WTO ruled out the use of trade protectionism as an instrument to boost industrialisation. Under the WTO rules, countries are not allowed use local content requirements; therefore countries tend to rely more on technological change and innovation in order to compete in the global market (Haque 2007).

In the automotive industry the post-apartheid government adopted the MIDP, which was modelled along the lines of the 1985 Australian auto industrial policy plan – the Button Car Plan (MITG 1994). Taking a lot from the government-initiated MITG report, in 1995 through the MIDP the government set the objective of increasing investment in the automotive sector to produce high-quality automotive vehicles and components for the domestic and global markets in the context of the TRIMS. This objective was to be realised through integration of the South African automotive industry into the global automotive industry; increasing production for the global markets and technical upgrading to increase labour productivity. Policy instruments to realise these objectives were trade liberalisation, export–import complementation and incentives to facilitate the upgrading and investment in the automotive sector. The MIDP had four main policy instruments, namely trade liberalisation, Duty Free Allowance, export-linked duty credits and Productive Asset Allowance (PAA). The automotive products manufactured in or exported from Industrial Development Zones were excluded from the MIDP incentives, and companies operating in the rest of southern Africa are entitled to the benefits of the MIDP (ITAC 2008).

The import duties for both completely built vehicles and Completely Knocked Down were reduced from 65% and 49% respectively to 25% and 20% in 2012 in order to comply with the WTO rules on liberalisation of trade and investment. The South African automotive industry is a highly globalised industry which manufactures and exports vehicles and components. It is estimated that 70% of the components of the South Africa-assembled cars are manufactured in a few factories in different parts of the world using very expensive and highly state-of-the art technological equipment; and 30% of the components are locally produced. The duty-free allowance incentive enabled South African-based vehicles assemblers to import components duty-free to the value of 27% of the selling price. They earned certificates that were used at customs to enable them to import duty free. As a result, vehicle assemblers that earned more credits could sell duty-free certificates to independent vehicle importers, thus undermining the MIDP's objective of increasing the number of vehicles manufactured in South Africa.

The PAA was meant to reward original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) that were investing in South Africa, and First Tier (that is, components manufacturers that supply directly to OEMs). Automotive companies investing in machinery and buildings qualified for 20% of their investment payable over a period of five years, which could be utilised to earn duty-rebate certificates to import in order to offset the duty payable on import vehicles by OEMs. The PAA enabled OEMs to import duty-free models that they were not producing in South Africa. To get access to the PAA, an OEM had to produce 20,000 cars per annum per model. Whilst it reduced the number of models produced in South Africa, as I will show, it increased the trade deficit in the automotive industry.

The MIDP was developed based on the assumption that exposure to international competition intensified through trade liberalisation would not only force companies to rationalise their models, but would also set conditions for higher rates of investment in the auto sector, which in turn would generate higher employment rates. To this end, the tariff protection on vehicles and components was reduced, and the local content requirements were also scrapped as they were prohibited by the WTO rules. Tariffs on built-up vehicles decreased from 65% in 1995 to 27% in 2010, and on components they fell from 49% in 1995 to 22% in 2010. Table 2 shows that tariff protection for vehicles has been reduced from 65% in 1995 to 26% in 2006. Figure 1 shows that the sector has been in a permanent trade deficit since 1970.

| Year | Built-up % | Original equipment components % |

|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 65 | 49 |

| 1996 | 61 | 46 |

| 1997 | 57.5 | 43 |

| 1998 | 54 | 40 |

| 1999 | 50.5 | 37.5 |

| 2000 | 47 | 35 |

| 2001 | 43.5 | 32.5 |

| 2002 | 40 | 30 |

| 2003 | 38 | 20 |

| 2004 | 36 | 28 |

| 2005 | 34 | 27 |

| 2006 | 32 | 26 |

Source: compiled from DTI data (http://www.dti.gov.za).

The MIDP decreased tariff protection and offered assistance to firms interested in increasing their exports. The encouragement to export was borne out of the small size of the South African domestic market as shown in Table 1: excess production would be exported to international markets; hence the state should step in to lower the costs of production and export. The MIDP’s economic logic had been that lower production costs and wider access to both domestic and global markets would enable South Africa to act as an export base for automotive firms, thus increasing automotive investment in South Africa. The MIDP came in as a set of government incentives aimed at increasing auto firms’ investment and to encourage them to produce for both local and international markets (DTI 1997).

In order to encourage firms to be competitive in the global and domestic markets, the vehicle assemblers (that is, OEMs) with the support of the state elite encouraged the domestic automotive companies to sell shares to transnational companies (Interview 3, Zavareh Rustomjee, 2013). This was to ensure that once transnational companies bought these companies, they would increase investment in production, including in technological upgrades and innovation, in order to make South Africa-based companies globally competitive. The state elite argued that the domestically owned automotive vehicle manufacturers on their own could not invest in advanced technological production methods to meet global competitive standards. Export volumes were to be used as a measure of the extent to which companies were globally competitive.

The MIDP introduced three main export-oriented incentives based on export–import complementation principles. The Import Rebate Credit Certificate (IRCC) facility, administered by the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), provided a rebate for auto exporters to import automotive components and vehicles duty-free. It basically awarded rebate certificates to exporters who use them to offset import taxes. This scheme enabled OEMs and components manufacturers to import components used in all production. Automobile exporters could earn tradable import credits codified in the IRCCs, which decreased the dutiable value of components (Flatters 2002). According to this scheme, for every rand of completely built-up vehicles exported, the firm was allowed to import one rand of completely built units or components duty-free. Similarly, components exporters could import duty-free one rand of the components they export on an equivalent basis. To illustrate, under this service a vehicle-exporting firm with local content of R200 million is allowed to import components or vehicles to the tune of R80 million if the duty-free import rate is set at 40%.

The export–import complementation incentives not only enabled firms producing for both the domestic and international markets to buy cheaper inputs, but also provided an incentive conducive to investment. In other words, firms producing for domestic and international markets were allowed to import inputs used to produce vehicles and components for the domestic and international markets without paying import tax. Firms that exported and invested in productive assets could earn IRCCs, which enabled them to import vehicles and components without paying duty. This offered a generous incentive for firms to buy cheaper inputs for making cars, which then encouraged them to invest in South Africa. Basically, the export–import scheme did two things: it allowed auto companies to import more cars and components in exchange for what they produced in South Africa for sale in both domestic and international markets, and it also allowed automotive firms to specialise in producing particular models while importing what they did not produce.

To respond to the potential decline in investment as a consequence of increasing imports associated with rebates linked to export performance, the 1999 MIDP review recommended the PAA. This was introduced in 2000, but firms that had invested in their productive assets from 1996 were allowed to benefit from this incentive. Vehicle and components manufacturers that invested in new plant and equipment were entitled to 20% rebates in the form of import-duty credits over five years. The DTI consultants had recommended 15% for the PAA, but this was increased to 20% after lobbying from BMW (Interview 2, Roger Pitot, 2012).

The MIDP also provided a Duty Free Allowance, which enabled vehicle manufacturers to import duty-free any original equipment components up to the value of 27% of the ex-factory price of a vehicle assembled for the domestic market. These schemes reduced the costs of imports for the vehicle and components producers by providing a subsidy for vehicle production. Between 1996 and 2003 the automobile sector received R55 billion for production and export subsidies, which includes all duties such as Duty Free Allowance, and over the period of eight years R21 billion went to two German luxury carmakers alone (Flatters 2005). The MIDP incentives, including the export subsidy, seem to have established a conducive environment for auto firms to invest in the South African auto industry. Since 1995, a number of auto firms have done so. In 1996, Delta (now owned by General Motors) opened its new assembly plant, in 1998 BMW spent R1 billion to upgrade the Rosslyn Plant located in Pretoria, and Daimler-Chrysler invested R900 million for a new body shop that same year, while Toyota invested R1.2 billion in a new paint and body shop (Black 2007).

The success of the MIDP programme lies in increasing South Africa’s investment and export performance (Kaggwa, Pouris, and Steyn 2007). Given the relatively small size of the South African auto market, the MIDP serves as an export base for South Africa-based multinational companies seeking to export their automobile products. The export subsidy had positive benefits for the OEMs in that the more they exported, the more they could import completely built vehicles without paying import duty. Figure 1 shows that in the period 1995 to 2010, automotive exports increased from 45% to 55% of total production. With the exception of Australia, the export destinations are the countries of origin of the South Africa-based auto multinationals, the OEMs.

Figure 1 further shows that the MIDP has not been able to curb the trade deficit in the auto sector because the policy favoured OEMs at the expense of local components manufacturers in that it made it easier to import components. In 2013, the automotive industry constituted 40% of the South African trade deficit (Parker 2013). The DTI complains that the overvalued exchange rate has been criticised for disabling export performance in that it has made it more expensive to sell vehicles and components globally and cheaper to import them, thus increasing the trade deficit. Furthermore, the global economic crisis, which also manifests itself in over-production of vehicles, has made it hard for South African automotive manufacturers to sell their products.

The rise in imports was encouraged by the MIDP despite its policy goals to increase exports and local production. That is to say, the programme increased both imports and exports. The duration of the IRCC is one year, but it is tradable and extendable. If a company has not used the IRCC within a year, it can apply for an extension. Furthermore, the exporting firms tend to sell their IRCC rebates to independent importers. To curb the trade deficit generated by the MIDP, the component manufacturers argue for an increase in local content requirements (Interview 2, Roger Pitot, 2012).

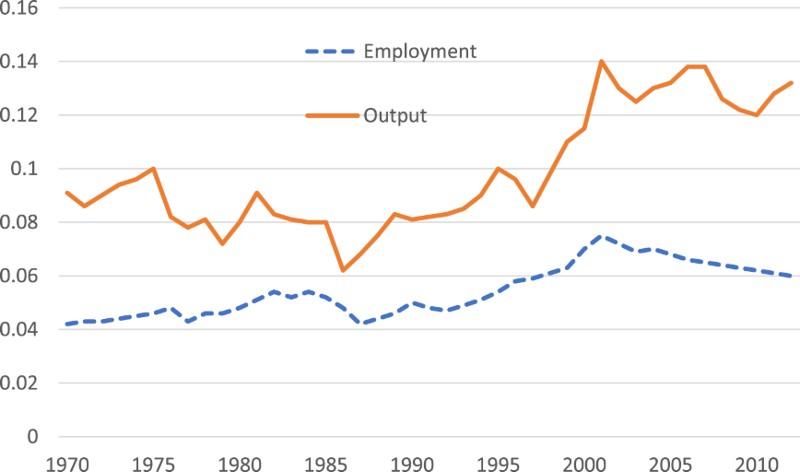

The MIDP has boosted export and investment performance, but that it has come at a huge economic cost for the state’s public finances, and to a certain extent for employment, is certain. It is estimated that the government contributes R2.6 billion for every R1 billion of investment by the automotive sector (Flatters and Stern 2008). However, Figure 2 shows that the auto industry’s contribution to total employment in the manufacturing sector has increased since the introduction of the MIDP, but has been on the decline – 8.2% in 2000 to 7.5% in 2007, just a year before the global economic crisis of 2008–09. However, the output has been higher, which means that the mechanisation of the labour process is higher.

Contribution of the automotive sector to South African manufacturing output and employment.

The export-support incentive essentially protects South Africa-based multinational automotive firms; consumers of the automobiles and the state itself bear the brunt of this protection. Under the MIDP, the state lost revenue owing to lower taxes associated with the import-duty-free policy (Flatters 2005).

Between 1990 and 1994 investment in the auto sector declined by 25%; however, after the introduction of the MIDP, investment increased by 84% between 1995 and 2000 in real terms (Kaggwa, Pouris, and Steyn 2007). Since the introduction of the MIDP, the production of both passenger and light commercial vehicles has increased (Economist Intelligence Unit 2012). The introduction of the MIDP has significantly boosted the profits of South Africa-based automobile multinationals. Figure 3 shows that the profit rate increased from 23% in 1996 to 42% in 2010. Using calculations from Flatters and Stern (2008), Figure 3 also shows that the profit rates would have been much lower had the MIDP subsidy not been introduced. In the absence of the state subsidy and incentives, the automotive manufacturers would have earned negative profits between 2002 and 2007.This means that without the MIDP the industry would not have made a profit.

Automotive industry: rate of investment (capital accumulation) and profits under the Motor Industry Development Programme.

Figure 4, shows that since the introduction of the MIDP, investment and profit rates in the auto sector have increased. Capital investment in the production of vehicles has increased from R847 million in 1995 to R3.5 billion in 2005, albeit lower than in developing countries such as Brazil, China, Thailand and Central Europe (Black 2009). Although Figure 3 shows an upward trend in the rate of investment, it has been lower in proportion to the profit rates, which means the auto companies are investing profits somewhere else. What is also interesting is that investment in the early 1990s was mainly about the acquisition of shares in South Africa-owned companies (Black 1996). Furthermore, it is estimated that the automotive industry received more than R100 billion worth of subsidies between 1995 and 2008, arising out of the import rebates and investment grants, whereas investment by the auto industry between 1995 and 2011 was R58 billion (Flatters and Stern 2008). The costs of the MIDP include forfeited import duties and direct subsidies. This means that more than 50% of the profits of the automotive industry came out of the MIDP subsidy. Therefore, it could be argued that the MIDP is a mechanism through which transnational companies extract more profits from the South African automobile industry.

Failure to install a developmental state and the rise of a business nanny state

There is no doubt that state capacity is a critical part of a developmental state since it enables the state to enforce discipline within the state itself and on private companies. However, the failure to establish a developmental state in South Africa does not lie with the state itself. Instead it lies in the lack of business interest in constructing a developmental state. To be sure, business using its structural power would have successfully installed a developmental state if it had wanted one. It is worth repeating that the whole notion of a developmental state is about denying business the absolute right to take investment decisions. In other words, discipline means that capitalists lose some freedom over where, when and how much to invest (Chibber 2003).

The increase in domestic competition through trade liberalisation provided leverage for the state to discipline business, including the coordination of investment in exchange for state support. Partly because of the small size of the South African market, the state used the MIDP to demand that automotive manufacturers produce for export. For its part, business demanded more assistance from the state. Business demanded that the state provide assistance to the automotive firms without disciplining the industry on a larger scale; the inability of the state to do so lies in the transnational nature and character of automotive vehicle manufacturers, as well as their strategies and interests in South Africa. Amsden (2009) has correctly argued that, with the exception of Singapore, it has been impossible to build a developmental state through transnational companies.

Liberalisation of trade and investment in the late 1980s and its acceleration in the 1990s have also led to a change in the ownership of the auto and other sectors. The South African financial sector has been dominated by ABSA, Nedbank, First National Bank and Standard Bank, which are largely foreign owned. To illustrate, ABSA is 56% foreign owned and Standard Bank is 40% foreign owned (COSATU 2012). In the steel industry, which is a critical input in manufacturing, the manufacturing company Arcellor-Mittal, established in 1928 under state ownership and previously known as the Iron and Steel Industrial Corporation, from 1989 became 65% owned by private, overseas capital. Liberalisation of the economy has led to an increase in the private and foreign ownership of the South African economy. The consequence is that the South African state has been trying to build a developmental state akin to South Korea largely based on international capital, particularly in the automotive sector.

By liberalising investment, the government hoped that parent companies would not only introduce new globally competitive production technologies, thus making South African industry competitive, but would also increase investment in their subsidiaries. During this period there had been mergers and acquisitions of various automotive firms. The merger of the Daimler and Chrysler companies was consistent with the patterns of mergers and acquisitions in the 1990s in which automobile firms responded to intense competition signified by overcapacity and falling profits. During this period, Ford acquired shares in Volvo, Aston Martin and Land Rover, and General Motors acquired a majority share in Daewoo (Finkelstein 2002).

Appendix 1 provides details of automotive manufacturers operating in South Africa in 1990, 2003 and 2010. It shows that in 1990, the seven car-manufacturing firms operating in South Africa were largely owned by South African businesses but operating under franchise agreements with the parent companies. However, these subsidiaries were not under serious global competitive pressures since they were not export oriented; hence they were also inefficient (Black 1996). Except for BMW and Volkswagen, which are 100% foreign owned, all the other car manufacturers were fully or partially owned by local business in 1990. Automakers were the manufacturers of Nissan and Fiat; Delta was producing Opel and Isuzu, with Samcor producing Ford and Mazda. While these auto firms were 100% locally owned, their designs, technological development and quality standards were determined by the parent companies. Half of Mercedes-Benz was owned locally, as was 72% of Toyota. By 2003 and 2010, these patterns of ownership had significantly changed.

Consistent with the general trend of the merger-and-acquisition form of investments in the 1990s, Appendix 1 also shows that in 2003 Automakers, now renamed Nissan South Africa, was taken over by its Japanese parent company, which increased its holding from 98% in 2003 to 100% in 2010. By 2010 Delta was fully owned by the American company General Motors, and Mercedes-Benz, after its demerger with Chrysler in 2007, was fully owned by the German company Daimler AG. Samcor and Toyota South Africa were also fully owned by their parent companies by 2010. As a consequence, the South African car-manufacturing firms have been fully integrated into the global strategies of their parent companies. This means the investment decisions and quality standards are determined outside the nation-states where these subsidiaries are located, even though the South African Bureau of Standards has some role in quality control.

There were no state attempts to control the investment decisions of the different firms except for using the MIDP to incentivise automotive firms to produce for exports, under conditions domestically agreed with the automobile industry, which required state support to be globally competitive. The state could have exerted more discipline on vehicle manufacturers to increase investment and reduce vehicle models in order to realise economies of scale. Establishing and expanding a domestically owned vehicle-manufacturing plant requires finance and borrowing on a macro scale as well as innovation and new technologies. However, the South Africa-based transnational automotive companies have already established local and international market networks and technological capabilities as well as finance, and did not need a state disciplinary apparatus akin to that of South Korea.

The transnational nature of the South African automotive industry based on foreign ownership is one of the factors that inhibited the state’s ability to control and coordinate investment in technological innovations, since investment decisions were taken in the headquarters of these multinational companies. The function of the South Africa-based automotive subsidiaries is mainly to manufacture and assemble automotive commodities, whilst research, development and design are carried out in the advanced capitalist countries, particularly in the countries of origin of the parent companies. To illustrate, Mercedes-Benz South Africa, which is 100% owned by Daimler AG, whose headquarters are located in Stuttgart, Germany, is responsible for investment locational decisions as well as design of its vehicles. Furthermore, as with all of the other automotive subsidiaries, Mercedes-Benz’s economic resource base does not lie in the South African state. The company can mobilise its funds outside South Africa without recourse to the South African state. There has been minimal research and development undertaken in South Africa to generate technologies that will make cars suitable for African conditions, including climate. On average, the automobile industry spends less than 4% of its total of research and development on safety technologies suitable for African conditions in South Africa.

The fact that the automobile companies have been transnational and foreign owned meant that automotive firms had relatively wider options to locate their production in different parts of the world based on access to markets and low production costs. Their subsidiaries had to compete with other subsidiaries located in other parts of the world. Under these conditions, where investment decisions were made in the companies’ headquarters, competition was not just between and amongst automotive firms. Subsidiaries of a particular company had to compete among themselves for a vehicle-production plant to be located within their country. Accordingly, the South Africa-based subsidiaries had to compete for the retention and attraction of investment with other subsidiaries located in advanced capitalist countries such as North America and Europe, as well as in less advanced but rapidly developing countries in Asia and Eastern Europe.

Like all other subsidiaries, automotive companies in South Africa bid for investment to make vehicles in South Africa. First, the decisions on investment location for the production of new vehicle models are made almost four years in advance. Subsidiaries bid for investment in areas where they are located. During the interviews all the German firms confirmed the well-established argument that assembly costs in Germany are expensive, hence they assemble in South Africa (Black 2009). However, South African labour costs are high compared with other developing countries. Toyota has been sourcing its main components from Thailand and Indonesia where labour is cheaper (Interview 2, Roger Pitot, 2012).

While low labour costs are a key determinant in driving the South Africa-based vehicle-manufacturing firms to invest in South Africa, automotive firms, individually and collectively through the National Association of Automobile Manufacturers of South Africa, pointed out that the MIDP had been the most important factor in their locational production decisions relative to South Africa. They all complained about the shortage of skills, poor infrastructure, particularly ports, and the prices of steel and electricity. Vehicle manufacturers consume about 7% of South Africa’s annual national production of steel (Jurgens 2009). Currently, steel pricing is based on import-parity pricing. This means that manufacturers buy domestically produced steel as if it is imported. As a result, the steel price drives their production costs.

Many firms bring senior technicians from Europe to assist with training local workers to operate new technology, particularly since 1996. Firms also complained about the infrastructure, particularly the ports through which exports are sent to external markets. The complaints about ports ranged from turnaround time to user charges. All the companies interviewed pointed out that all these problems were offset by the MIDP’s subsidies. So the MIDP is of strategic significance for the transnational vehicle manufacturers in that it enables them to source components and models produced outside South Africa duty-free, while subsidising transport costs to markets that are geographically far from South Africa.

The South African state has been dealing with automotive companies that do not face problems with regard to entry into domestic and international markets, access to sales networks, technological innovative capacity or access to finance. To be sure, the total acquisition of South African subsidiaries has also made it possible for them to use existing networks. So it is clear that the state needs capital more than capital needs the state in areas such as technological innovation, finance and market networks. Aside from their concerns about production costs, the South Africa-based subsidiaries are mainly using South Africa as a market outlet (small as it is), and as an export base to external markets, notwithstanding the long distance from South Africa.

The MIDP is a business-incentive structure that facilitated conditions for automobile companies to use South Africa as a market outlet and export platform, even though exports were higher than domestic sales only by 2009, hence the current-account deficit in the automotive industry. It is for this reason that South Africa-based automotive multinationals were not interested in the construction of a developmental state.

There has been a significant increase in the South African domestic market between 1995 and 2005. Domestic sales constituted 64.9% of domestically produced vehicles in 2005. It has been suggested that the increase in domestic sales in this period was driven by the rise of the post-apartheid black middle class (Jurgens 2009). Exports grew faster than domestic sales in 2009, constituting 57.7% of the total local production.

The increase in automotive investment between 1996 and 2010 is associated with the companies’ interest in capturing the domestic market and maximising export gains associated with the MIDP. During this period, the largest percentage of automotive investment had been for productive and exports facilities and other export programmes of the investing companies in order to maximise their exporting and productive capacity.

Conclusion

The post-apartheid government’s endeavours to attract investment have been taking place in the context of intensified global competition facilitated by trade liberalisation. In trying to retain and attract investment, and under structural pressure from business, the post-apartheid government adopted neoliberal macroeconomic and microeconomic policies, which increased competition in the South African domestic market. While the ideology of neoliberalism suggests that the state does not intervene in the economy, the reality in the South African context is that, through its microeconomic interventions, the state provided more concessions to business in order to increase the rate of investment and economic growth.

The automotive industrial policy, the MIDP, was a policy instance that showed that the state intervenes in the interest of business through the provision of business-friendly concessions accompanied by the dismantling of higher trade tariffs built during the ISI dispensation. In order to ensure that the South Africa-based automotive subsidiaries remained competitive in the domestic market, but more especially in the international markets through exports, the state adopted the MIDP based on supply-side measures including export rebates and investment incentives. The MIDP as an automobile industrial policy was largely based on the import–export complementation principle, which allowed South African automotive firms to earn import-duty-free rebates in exchange for their export-performance investment in production in South Africa.

The post-apartheid state did not only embark on trade liberalisation and export promotion, but it also encouraged and supported the transfer of ownership of automotive vehicle manufacturers to transnational companies through the buying of shares from South African shareholders. This move was based on the idea that transnational companies would increase investment in advanced production techniques, and the South Africa- based automotive sector would be fully integrated into global automotive production. This resulted in further denationalisation of the South African automotive capitalist class, which was replaced by the transnational capitalist class. In the period before the early 1990s, South Africa-based automotive firms were locally owned and had no control over technology since they operated on licences. The denationalisation ruled out any possibility for the local business to embark on reverse engineering or technological espionage, which had been the strategy of almost all late developers (Chang 2002).

Investment rates have increased since 1994, although they are still low compared with the late 1970s and early 1980s, and this had to do with the transnational automotive companies upgrading their productive capacity as part of their global competitive strategy. In so doing, they also use their structural power, accompanied by threats to withdraw their investment, to get more concessions from the state. Instead of imposing policy discipline, which included the state’s involvement in jointly agreeing with the private sector on where and how much to invest, the state’s industrial policy simply gave more concessions, which increased profit rates.

The increases in profit and investment were at the expense of employment, labour share and a widening trade deficit. Put differently, through the MIDP the state had set up a business-incentive structure which increased exports, investment and profits in the automotive industry. However, the profits have increased more than the investment rates, and imports have increased more than exports, thus perpetuating the trade deficit. Furthermore, unemployment has increased under the MIDP. The automotive industry has relied on state support for its global competitiveness, which means that without the MIDP the industry would not have survived in South Africa.

The failure to install a developmental state in the South Africa-based automotive industry was not due to institutional deficiencies. Objectively, the South Africa-based automotive industry does not face the hindrances faced by late developers such as South Korea. The South Africa-based automotive transnational companies are largely interested in the internationalisation of their production and distribution. They use South Africa as an export base, and they do not need state support for technological innovations since decisions on these matters are located in their respective headquarters outside South Africa. Therefore, they enjoy state handouts without state discipline. Consequently, South African automobile industrial policy has nursed these multinational automotive firms to increase local investment and exports. In order to maximise the gains associated with the MIDP incentive structure, the vehicle manufacturers increase investment to upgrade their productive and export facilities. In their pursuit of the domestic market, the manufacturers produce certain models locally and import models they produce outside South Africa. The MIDP enables them both to import vehicles and components duty-free and to maximise their access to rebates, which enables them to import as they increase their exports.

The strategies of the South Africa-based automotive subsidiaries show that the expansion and retention of capitalist automotive investment in South Africa have been driven mainly by access to the domestic market and the MIDP, which generously rewards export performance. On the other hand, the state cannot channel and coordinate investments because of the current transnational nature of the automobile manufacturers and the international division of labour, which allocate certain production functions such as technological innovation outside the nation-state. Also, these companies have long-established markets and networks. As a result, the state was rendered irrelevant in the coordination of investment, except for providing incentives which have propped up the falling profit rates in South Africa. The state does not direct where and how auto capital should be invested because the South Africa-based automotive firms do not face barriers similar to East Asian countries such as technological innovation and penetrating global markets. The MIDP is not typical of an auto industrial policy in a developmental state; instead, it resembles a nanny state which hands out largesse to the private sector to boost export performance.