Introduction/Literature Review

The main objective of this paper is to question if consumers who are exposed to high levels of compassionate emotional imagery messaging increase their likelihood of purchasing Fair Trade products than consumers who are exposed to low levels of compassionate emotional imagery messaging. In other words, messaging that is composed of high levels of compassionate emotional imagery will attract greater customer patronage than messaging that is composed of low levels of compassionate emotional imagery.

In this conceptual study, compassionate emotional imagery exposure (CEIE) is newly introduced and will serve as an independent variable. CEIE is defined as the extent to which a message (e.g., visual and text) contains information intended to evoke individuals’ feelings of compassion.

Imagery and emotional imagery literature

A review of the imagery literature shows that much research has been conducted on people’s ability to imagine or virtually sense sound, smell, taste, sight and touch (Krishna, 2013; Krishna, Morrin & Sayin, 2014; Morales & Fitzsimons, 2007; Peck & Childers, 2012; Perky, 1910; Raghubir & Krishna, 1999). For example, in her book Customer Sense, Aradhna Krishna advises that ‘there can be more to a product that meets the ear, nose, mouth, eyes or fingers (p. 5) … sensations can be imaged by the human mind’ (p. 11). In addition, Krishna and colleagues (2014) advise that ‘visual imagery involves imagining what an object looks like while one is not actually seeing the object or event’ (p. 18). Furthermore, Krishna et al. (2014) study consumers’ ability to imagine or virtually sense smell and found that the individual’s reactions to food advertisements were meaningfully affected only when the individual was able to imagine an intense depiction of the scent referent. Also, Morales & Fitzsimons (2007) conducted research on how consumers’ purchasing decisions are influenced by their perceptions of imagining ‘contamination’ (the transfer of negatively perceived product attributes) between items and found that product contagion exists among consumers. Moreover, Raghubir & Krishna (1999) studied consumers’ perception of product volume (i.e., product elongation shapes) and found that the product shape affects an individual’s perceptions about its volume and that affects their consumption behaviours including, but not limited to, post consumption.

In this study, the concept of imagery is taken a step beyond the five senses to the sense of feelings. The study considers the effects of the subject’s ability to imagine or virtually sense certain emotions. This is called Emotional Imagery (Lang, 1979). Emotional Imagery Theory (Lang, 1979) ‘conceives the image in the brain to be a conceptual network, controlling specific somatovisceral patterns, and constituting a prototype for overt behavioral expression’ (p. 495). Among the emotional imagery researchers, Preston and colleagues (2007),

investigated the neural substrates of cognitive empathy, defined as the deliberate attempt to effortful imagine what it is like to be in the emotional situation of another person as if it is happening to you. The results suggest that the substrates of cognitive empathy depend in large part on how well the participant can relate to the situation of others. [Moreover], when we cannot relate to the experience of the other, presumably because we do not have records of comparable feelings and situations from our own past experience, we can achieve empathy by literally trying to imagine what it is like to be the other person, in keeping with traditional perspective-taking theories of empathy, which describe empathy as “putting oneself in the place of another’ or “imaginatively projecting oneself into the situation of another”.

(pp. 272–273)

For example, according to Maclnnis & Jaworski (1989), ‘consumers who identify with the characters in [an] ad may experience intense emotions. In fact, the act of identification may be required for the emotional intensity’ (p. 14).

Thus, because emotional imagery can involve imagining what a situation feels like for someone else while the observer has never met the individual or experienced their lifestyle, this paper poses the question: Can individuals who are exposed to certain levels of compassionate emotional imagery develop the emotion of compassion? And if so, can the evoked emotion lead to sales of a certain product category, such as Fair Trade?

The next section explains why Fair Trade products are an ideal commodity to use for this paper.

Fair Trade

A review of the literature shows there is growing demand for companies to implement Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) policies (Bhattacharya & Sen, 2004; Castaldo, Perrini, Misani & Tencati, 2009; Craig & Allen, 2013; Harwood, Humby & Harwood, 2011; Matten, Crane & Chapple, 2003; Wicks, Keevil & Parmar, 2012). Aligned with the growing demand for sustainable products and CSR, Fair Trade business initiatives have increased in recent years.

Fair Trade is a form of sustainable business and it encourages entrepreneurial endeavours among communities in developing countries (Blowfield & Dolan, 2010). Organizations that participate in Fair Trade typically adhere to the following ten principles, which have been approved by the World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO):

1) creating opportunities for economically disadvantaged producers, 2) transparency/accountability, 3) fair trading practices, 4) fair payment, 5) ensuring no child labor or forced labor, 6) commitment to non-discrimination, gender equity and freedom of association, 7) ensuring good working conditions, 8) providing capacity building, 9) promoting Fair Trade, and 10) respect for the environment.

The following section explains why emotional imagery can facilitate and/or enhance the consumption of Fair Trade products.

Emotional imagery and Fair Trade

Researchers, such as Davenport & Low (2012) have found that

the imagery of Fair Trade craft producers as “artisans” invokes a vision of people within a community who live either entirely by their craftwork or supplement their agricultural livelihood with cash income from traditional handicraft such as knitting or basket weaving. This image of independence, tradition, and skill meshes well with the message of empowerment through Fair Trade: artisans have the means to a “good life” if they are given a chance, i.e. a market and a fair price. The idea of marginalized people controlling their own destiny and making a better living through their traditional handcraft skills, which are purchased on a Fair Trade basis by Northern consumers [customers living in the Northern Hemisphere], is a powerful marketing message.

(p. 336)

For example, these authors reference a quote from the CEO of the Fair Trade Federation (FTF), advising that ‘Fair Trade is a very difficult concept to get over … you’ve got to paint the picture. And the best way to paint a picture is to tell the story of the impact it’s made’ (p. 345).

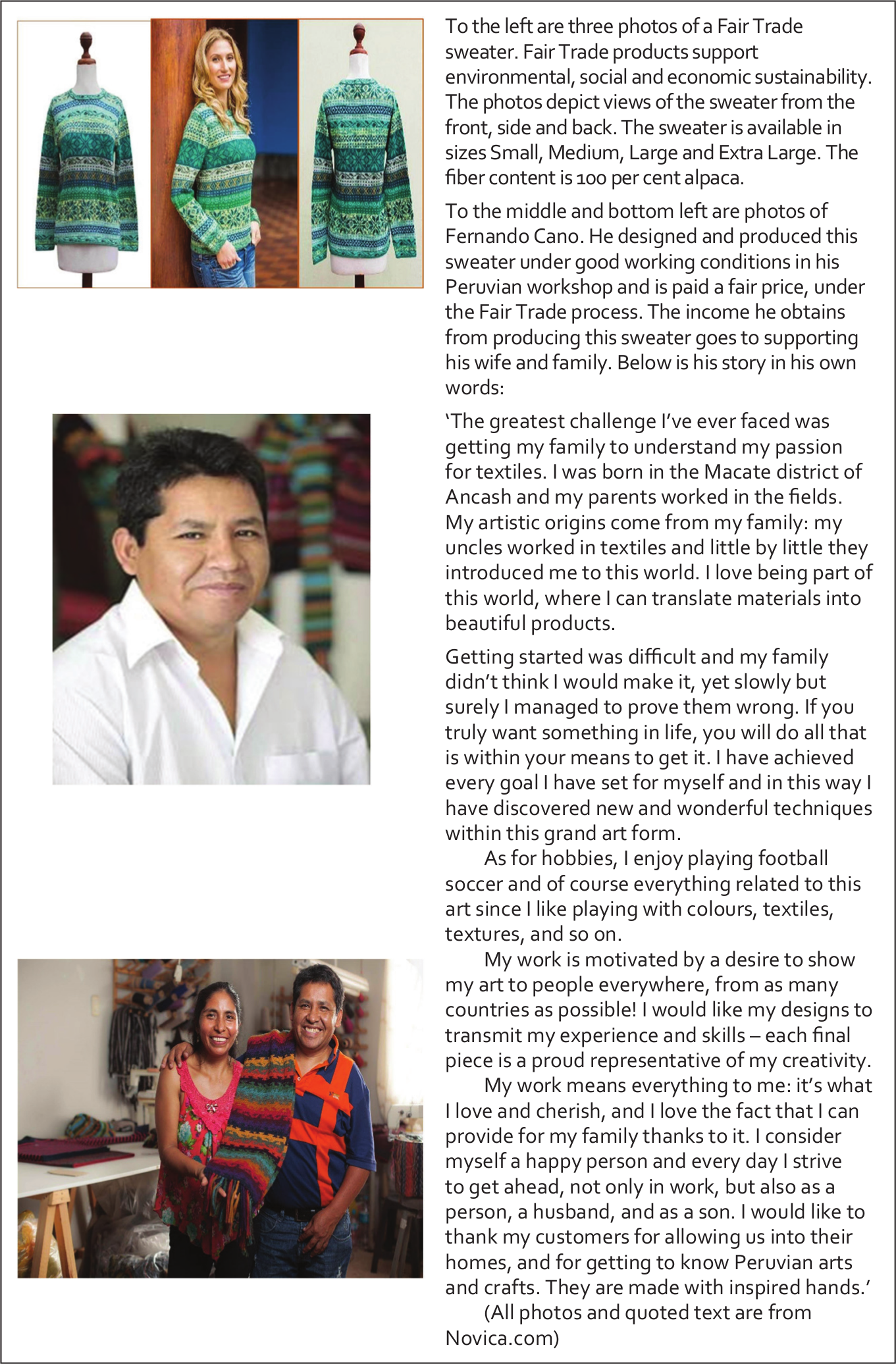

As discussed earlier, CEIE is defined as the extent to which a message (e.g., visual and text) contains information intended to evoke individuals’ feelings of compassion. This is relevant to Fair Trade sales, as it is likely that many Fair Trade consumers are concerned about societal and environmental stewardship. In addition, because Fair Trade products might cost more than alternative non-Fair Trade products, due to ensuring compliance with the ten above-mentioned Fair Trade principles, it is likely that CEIE may support individuals in justifying their Fair Trade purchase. Fair Trade sales may be improved by evoking consumers’ emotions via storytelling, which highlights the product’s positive societal and environmental impacts (Davenport & Low, 2012). Therefore, it is expected that when an individual (a) sees photos of a Fair Trade worker and their sustainable product and (b) reads about the life of the worker (some of whom are from marginalized societies) and the positive environmental impacts of their product, the CEIE messaging can evoke the emotion of compassion not only for the Fair Trade worker but also for the environment. For instance, these compassionate emotions may also be aligned with feelings of non-duality or interconnectedness between the consumer and the worker due to the societal and environmental stewardship promoted in the CEIE messaging.

Compassion and Social Identity Theory

In the previous sections, the reasons for creation of the compassionate emotional imagery exposure (CEIE) independent variable, supported by Emotional Imagery Theory, were discussed. In this section, the significance of incorporating compassion into the theoretical models is addressed.

Prior research (Musa, 2015; Musa & Gopalakrishna, 2021) introduced and identified the importance of Fair Trade consumers having the attributes of compassion for oneself, others and the environment (COOE) as it relates to Fair Trade consumption, supported by Social Identity Theory. According to Bhattacharya, Korschun, & Sen (2009), Social Identity Theory ‘describes how individuals categorize themselves as members of social groups or organizations’ (p. 264). For instance, ‘identification represents a sense of oneness between an individual’s self-concept and their concept of the group or organization with which they consider themselves a member. This overlap of values can be heard anecdotally when references to “I” become references to “we”’ (p. 264). Neff (2003) describes compassion as,

being open to and moved by the suffering of others, so that one desires to ease their suffering. It also involves offering others patience, kindness and non-judgmental understanding. Self-compassion is directly related to feelings of compassion and concern for others. The process of self-compassion [includes] decreasing ego-centric feelings of separation while increasing feelings of interconnectedness.

(p. 224)

Musa & Gopalakrishna (2021) link Social Identity Theory to COOE, which is described as ‘the extent to which a person is caring, patient and respectful towards themselves, others and the environment’ (p. 35).

Thus, COOE is aligned with Social Identity Theory. For example, depending on the individual’s level of COOE, they may be able to view themselves in someone else’s shoes (i.e., the individual may imagine themselves as the Fair Trade worker). Furthermore, in a purchasing scenario, depending on the amount of CEIE, moderated by the individual’s level of COOE, they might be motivated to purchase the Fair Trade product. Moreover, in a non-purchasing scenario, it is expected that the higher the level of CEIE, the greater the likelihood that the individual’s COOE will increase.

The following sections document the hypotheses and models for both a purchasing and a non-purchasing scenario.

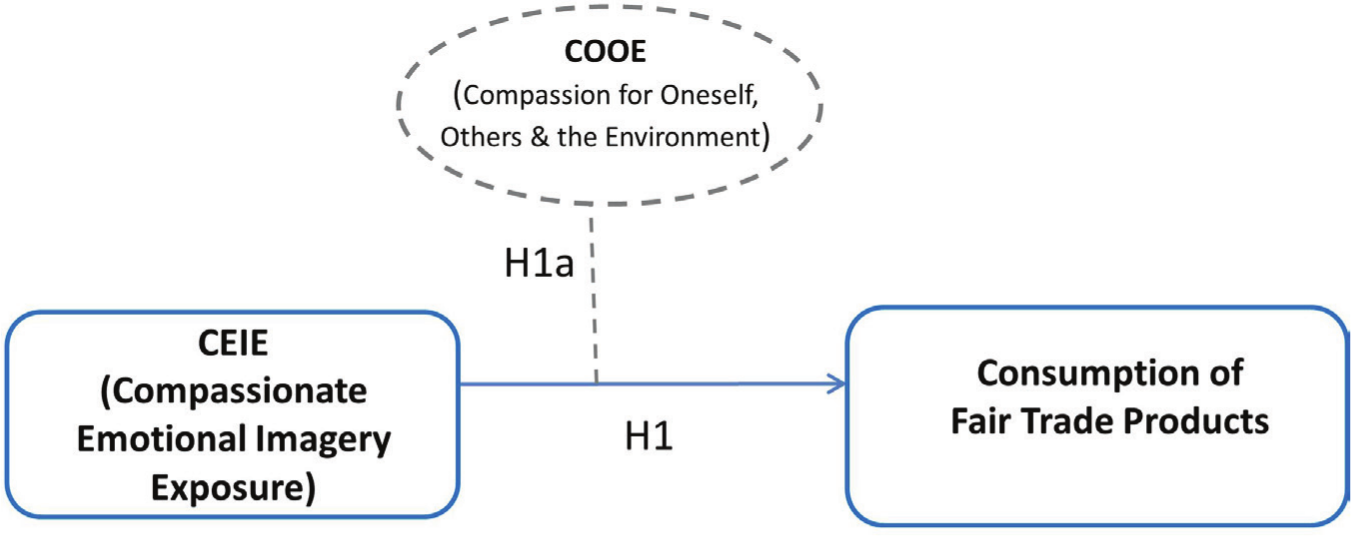

Hypotheses and Model for Purchasing Scenario

Hypothesis 1: Purchasing scenario

H1 – The greater the consumer is exposed to CEIE (compassionate emotional imagery exposure), the greater the likelihood that they will purchase a Fair Trade product.

H1.a.1 – The higher the consumer’s COOE level, the greater the likelihood that they will engage in Fair Trade consumption when exposed to No or Low Level of CEIE.

H1.a.2 – The lower the consumer’s COOE level, the lesser the likelihood that they will engage in Fair Trade consumption when exposed to No or Low Level of CEIE.

H1.a.3 – Regardless of the consumer’s COOE level (e.g., low or high), they will likely engage in Fair Trade consumption when exposed to High Level of CEIE.

Examples of (a) No CEIE, (b) Low CEIE and (c) High CEIE

This section depicts examples of (a) No CEIE, (b) Low CEIE and (c) High CEIE. As discussed earlier, CEIE is defined as the extent to which a message (e.g., visual and text) contains information intended to evoke individuals’ feelings of compassion.

Suggestions for Future Research

Scholars could use similar photos and text as shown above to test the hypotheses in an experimental setting and conduct at least two unique studies.

For the first study, testing hypotheses H1 through H1.a.3, three condition groups for CEIE can be created. In the first condition group, participants can be exposed to the No CEIE image and text. In the second condition group, subjects can be shown the Low CEIE (i.e., a photo of the Fair Trade worker and a short paragraph about their life). In the third condition group, participants can be shown the High CEIE (i.e., photos of the Fair Trade worker and a few paragraphs about their life). In a purchase scenario, the goal of the CEIE messaging is to evoke the emotion of compassion in consumers so they may experience a connection to the Fair Trade worker and likely buy the Fair Trade product.

To test the likelihood that participants would purchase the Fair Trade product based on their levels of CEIE, participants can be asked to indicate their likelihood of purchasing the product based on a five-point Likert scale, anchored by level 1, ‘no desire to purchase/will not purchase’, and level 5, ‘strong desire to purchase/will definitely purchase’. In addition, to measure an individual’s COOE, researchers can incorporate questions from the COOE scale (Musa & Gopalakrishna, 2021) as a moderator variable. Musa & Gopalakrishna’s (2021) COOE instrument

uses a five-point Likert Scale with twelve items, seven of which were adapted from [Neff’s Self Compassion scale (2003, pp. 231–232)] and the remaining five were adapted from [Stone, Barnes & Montgomery’s ECOSCALE (1995, pp. 603–604)]. Below are the original twelve questions:

1 - I am kind to myself and others when I or others are experiencing suffering. SCS (Question 2, p. 231)

2 - When I am and others are going through a very hard time, I give myself or them the caring and tenderness I or they need. SCS (Question 3, p. 231)

3 - I am tolerant of my own and others’ flaws and inadequacies. SCS (Question 4, p. 231)

4 - I try to be loving towards myself and others when I or others are feeling emotional pain. SCS (Question5, p. 231)

5 - I try to be understanding and patient towards those aspects of my and others’ personality, which I am not fond of. SCS (Question 1, p. 231)

6 - When I feel inadequate in some way, I try to remind myself that feelings of inadequacy are shared by most people. SCS (Question 11, p. 231)

7 - When something upsets me, I try to keep my emotions in balance. SCS (Question 19, p. 232)

8 - It is no use worrying about environmental issues; I can’t do anything about them anyway. (Reverse Coded) ECOSCALE (Question 30, p. 604)

9 - My involvement in environmental activities today will help save the environment for future generations. ECOSCALE (Question 17, p. 604)

10 - I do not purchase products that are known to cause pollution. ECOSCALE (Question 25, p. 604)

11 - Economic growth should not take precedence over environmental considerations. ECOSCALE (Question 5, p. 603)

12 - The earth’s resources are finite and should not be used to the fullest to increase the human standard of living. ECOSCALE (Question 6, p. 603).

(pp. 36–37)

In addition, other factors at play in a purchasing decision include (a) product quality, (b) price, (c) competition (both from Fair Trade and non-Fair Trade products), (d) perceived value, and (e) shopping mode (e.g., for oneself or someone else). Therefore, these variables have been incorporated into Model 1 as control variables. This will allow scholars to isolate each variable and examine its effects on the purchasing scenario.

Furthermore, while studies have demonstrated that Fair Trade consumers typically hold the attribute of compassion and benevolence (Musa & Gopalakrishna, 2022; Doran, 2009), it is important to note that there are some individuals who purchase Fair Trade products primarily for their high quality and distinctive aesthetics. Therefore, scholars could conduct future studies to determine the extent to which CEIE messaging influence these consumers, for example, testing this paper’s hypothesis H1.a.3: Regardless of the consumer’s COOE level (e.g., low or high), they will likely engage in Fair Trade consumption when exposed to High Level of CEIE.

For the second study, testing hypothesis H2, scholars can examine the CEIE effect on COOE in a non-purchasing scenario. They may determine if certain images and text, which exclude references to a purchasing scenario, evoke the emotion of compassion by measuring the participants COOE levels before and immediately after they experience one of the CEIE conditions and compare the results.

Contribution to Practice

This topic has theoretical and practical dimensions. Theoretical dimensions are addressed in the next section. In terms of practical dimensions, the research provides a foundation for scholars to conduct empirical studies testing these hypotheses. The results may assist companies and organizations that sell Fair Trade products. For example, global Fair Trade sales are substantially lower than the sales of conventional products and this sales gap may decrease via High CEIE messaging, which can potentially increase the demand and sales of Fair Trade products.

In addition, this research posits that Fair Trade companies and organizations don’t have to limit their messaging only to consumers who practice a sustainable lifestyle. They can also target a broader range of consumers through higher levels of CEIE and potentially increase sales.

Contribution to Academia

To start with, this novel research builds upon and adds value to Social Identity Theory, Imagery and Emotional Imagery literature by introducing CEIE and incorporating COOE into the analysis. Based on a review of the literature, thus far, a study could not be found which posits the role of COOE as a moderator between compassionate emotional imagery exposure and Fair Trade consumer behaviour. Moreover, this paper provides scholars with suggestions on testing the effect of CEIE on COOE. Researchers may determine if certain images and text evoke the emotion of compassion in a non-purchasing scenario. This can also be beneficial for organizations that want to promote environmental and societal ideas and need to gain support from individuals who are inclined to hold the attributes of COOE. The organizations may be able to accomplish their goals though High CEIE messaging.

In addition, due to the popularity and growth of sustainability, this timely research can be valuable for academics and practitioners because it can contribute to the current Fair Trade, compassion and ethical business marketing literature; it can build upon the above-mentioned academic theories and the sustainability marketing body of knowledge through specific focus on Fair Trade and compassion research.