Introduction

…if a life is not grievable, it is not quite a life; it does not qualify as a life and is not worth a note. It is already the unburied, if not the unburiable. ( Butler 2004, 34)

Recent works have documented how art in its various manifestations has been used as a tactic of resistance ( Aidi 2014; Drury 2017; Khan 2007; LeVine 2015; Serazio 2008; Tas‚ 2017; Zine 2022). From graffiti, street, and gallery art to different genres of music and poetry, artistic interventions have communicated messages of peace, resistance, and identity politics against the state and societal powers of oppression, containment, and erasure. However, there is scarce analysis of the different ways in which collective mourning and grieving utilize art as a form of communication. In this paper, we 1 examine a particular genre of artistic works which symbolically contest Islamophobia through reinterpreting and humanizing the victims of Islamophobia. We focus particularly on the digital artifacts that were circulated on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook immediately after the tragic murders of the victims of the Quebec Mosque Shooting (2017) and the Afzaal-Salman family members (2021) in Canada. Both of these events are recent in public memory. The digital artifacts that were circulated represent the digital afterlife of the tragedies ( Harju and Huhtamäki 2021). We begin by defining what constitutes a digital artifact and how it is constitutive of an ensemble of meaning. We then situate these artifacts within the literature on digital expressions of grief and mourning. Thereafter, we analyze specific digital artifacts that were circulated in the aftermath of both tragedies. We explain how these artifacts are constitutive of ensembles of meaning, combining different registers of affect and resisting hegemonic tendencies of forgetting through erasure, or being buried beneath an avalanche of contemporary issues and concerns. We argue that mourning and grief are harnessed through these artifacts, to contest Islamophobia and push for social change.

Grief on the Digital Plane

There is now a robust literature that has examined the use of technologies in facilitating processes of grieving and memorialization. Thus, researchers have documented an expansive array of digital memorials and cyber-cemeteries such as the Virtual Memorial Garden ( Roberts and Vidal 2000; de Vries and Rutherford 2004), as well as memorials on social media sites such as Facebook and MySpace ( Brubaker et al. 2013; Karppi 2013; McEwen and Scheaffer 2013), and on YouTube Vlogs ( Gibson 2016; Harju 2015). These digital memorials enhance temporal, spatial, and social expansion, thereby allowing for a greater number of individuals to participate in death rituals of remembrance ( Bennett and Huberman 2015; Graham et al. 2015). Additionally, these digital remembrances are constitutive of mediatized rituals ( Cottle 2006). Brubaker et al. (2013) underscore the affordances of social media platforms in enabling the continued commemoration of the deceased, contending that such internet sites permit for different stages of grieving, over longer periods of time in a more public fashion ( Carroll and Landry 2010). Examining these memorials as public stories about lives lived also provides insights to the survivors, and the bereaved, whose concerns, realities, and anxieties are expressed in these memorials. Moreover, the permanence of digital memorial content can be said to offset the absence of the deceased by creating representations of them that live on indefinitely ( Egnoto et al. 2014).

Existing literature suggests that, for marginalized groups, access to these technologies allows for a collective grieving of what Butler (2004) has described as “ungrievable bodies,” i.e., bodies that are not considered worthy of public mourning. Relatedly, Doka and Aber (1989, 7) also reference how these vernacular memorials act as vehicles for the expression of disenfranchised grief suffered by “those whose grief occurs in relationships with no recognizable kin ties; those whose loss is not socially defined as significant and those who are perceived to be incapable of grief.” These forms of vernacular memorial-making ( Maddrell 2012) then enable the expression of subjugated stories articulating the experiences of the marginalized. Haskins (2007, 403) elaborates this further when she argues: “In contrast with the hegemonic official memory, vernacular practices of public remembrance typically assume decidedly ephemeral forms such as parades, performances, and temporary interventions. Instead of somber monumentality, they employ non-hierarchical, sometimes subversive symbolism and stress egalitarian interaction and participation.”

In the context of widespread Islamophobia, Muslims are marginalized in many ways. Despite significantly higher levels of education in Canada, they remain underemployed and underrepresented in high-paying jobs. That aside, they are constantly subjected to daily and systemic Islamophobia ( Bahdi 2019; Mercier-Dalphond and Helly 2021; Nagra and Maurutto 2020; Razack 2008; Siddiqui 2015; Truelove 2019; Wilkins-Laflamme 2018; Zine 2022). Studies focusing on media representations of Muslims in Canada have consistently underscored their negative portrayal as barbaric, terrorists, and unruly others who have no place in the nation-state, or who must conform to the docile, eternally grateful immigrant to be tolerated at best ( Haque 2010; Jiwani and Dessner 2016; Karim 2000; Mahrouse 2018; Odartey-Wellington 2011; Siddiqui 2022). Accessing digital media then becomes a way in which Muslim victims of daily violence and tragedies can be remembered by their kin and the larger Muslim and non-Muslim communities.

Digital Ensembles of Mourning

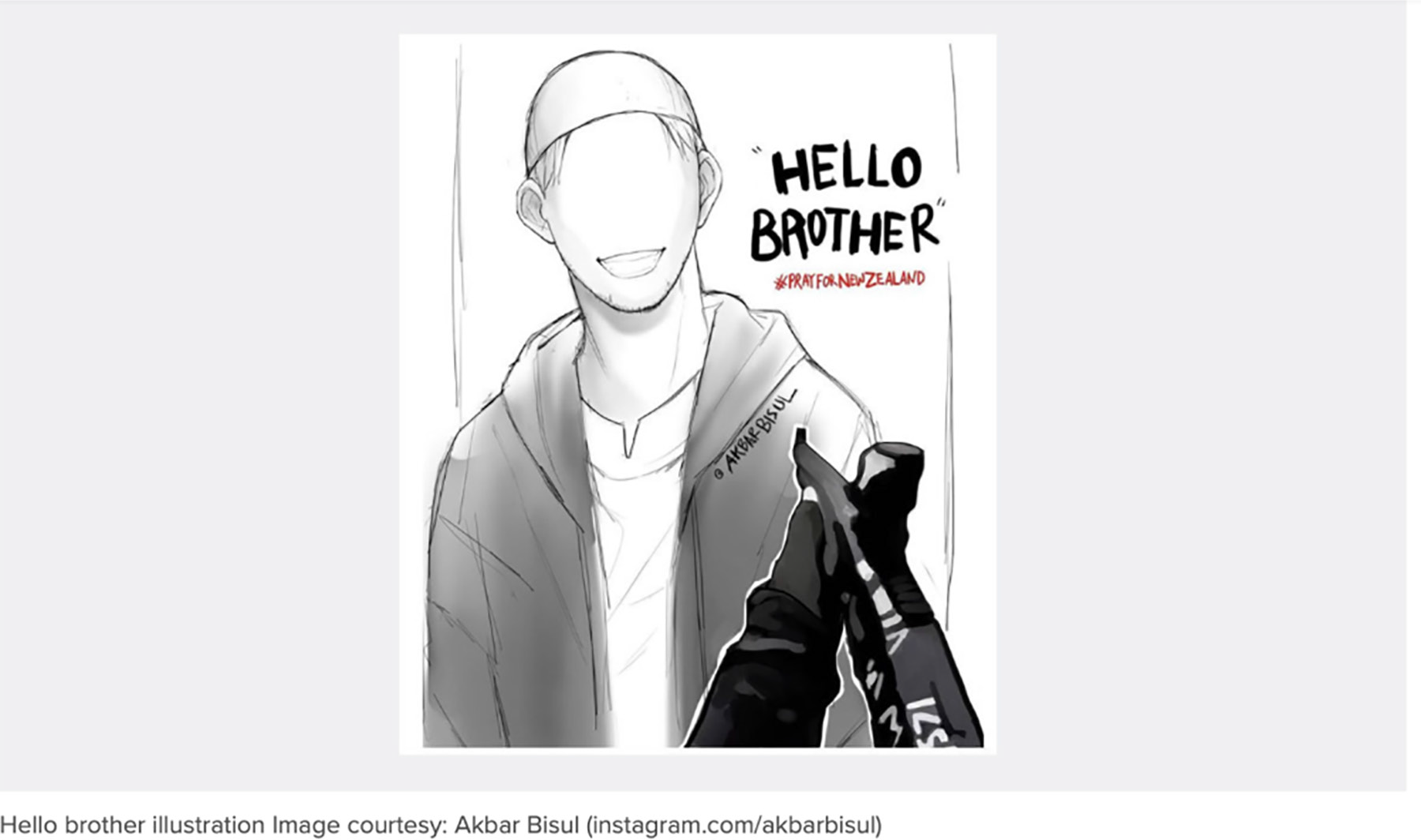

March 15, 2019 is the day when Muslim worshippers at the Al Noor and Linwood mosques in the city of Christchurch in New Zealand, were murdered by an armed gunman. Fifty-one people were murdered that day and many others injured. The killer livestreamed his attack on social media and circulated his manifesto which, to this day, has continued to inspire other Islamophobic and racially motivated murders. In their article concerning the circulation of the hashtag #Hellobrother in the aftermath of the 2019 Christchurch Mosque shooting in New Zealand, Harju and Huhtamäki (2021) argue that such hashtags, along with memes and artistic illustrations, constitute solidarity symbols that serve to cohere affective networks of sociality. Underpinning these networks are communities of practice that “share a common goal and a shared understanding but also engage in a temporally continued manner in a shared endeavor ( Eckert 2006) that positions the community in relation to the world; for example, sharing in commemorative practices online constitutes such a community” ( Döveling et al. 2018). The emotional alignment of these affective cultures offers their members a sense of belonging and identity. In the case of the #Hellobrother hashtag, the messages of mourning and condolences were not only channeled through the hashtag, but the hashtag also communicated a visual reminder of how the first victim of the 51 people who were killed, Haji Daoud Nabi, had greeted the gunmen with the words “Hello Brother.” The trending power of this hashtag was immediately apparent as it symbolized Islam as a religion of peace, but also underlined how a welcome of this kind can be the last words uttered by an innocent victim of Islamophobic violence ( Figure 1).

As Harju and Huhtamäki (2021, 236) put it: “Importantly, #hellobrother managed to disrupt the hegemonic culture of mourning after terror where the dominant figure that elicits empathy is the white Western victim and the subjectivity allocated for the Muslim subject is that of a perpetrator. We find that #hellobrother was successful in channeling solidarity to the Muslim community.” Their observations are particularly relevant in light of the heavy emphasis of the mainstream media in constructing perpetrators of Islamophobia as “lone wolves” and/or as singular cases of deviance ( Kanji 2018).

High-profile tragedies motivated by Islamophobia such as the Christchurch Mosque shootings in New Zealand, the Quebec Mosque shootings where a gunman attacked and killed six men and injured 19 others at the Centre Culturel Islamique de Québec in Ste Foy in Quebec city, and the murders of the Afzaal-Salman family members who had gone out for an evening stroll in their city of London, Ontario, generate their own symbols of solidarity which, through digital networks, become widespread as a result of the shareability and spreadability amplified by the speed of social media platforms. This is akin to the ways in which social media are used to express and circulate an affect of grief in memory of the deceased. Examples of this are apparent in the deaths of celebrities like Whitney Houston ( Strong and Lebrun 2015), and Steve Jobs ( Harju 2015). These connective forms of hyper-mourning “encompass cases of sharing immediate, intense emotional reactions to death news. Such forms are illustrated in hashtag mourning in the wake of terrorist attacks, for example in the case of the social-mediatization of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, which took place in January 2015” ( Giaxoglou and Spilioti 2020, 12).

However, these symbols also function as forms of digital afterlives—they persist after the tragedy because of the technological affordances of various platforms that enable their cross-platform relationality. They also live on in terms of their commemorative value in recalling the lives of the victims. It is this double aspect of their afterlives that merits attention because of the cumulative impact on cultural memory as well as the recirculating of the affect of grief and mourning. Nested as they are in various digital platforms amongst other digital artifacts on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and less dominant social media, these symbols circulate widely and have the potential to harness other users, thereby widening the affective cultures of grief. As Harju puts it, “the digital artefact comes to define the emotional and ideological landscape of the space it creates and contextualizes” ( Harju 2015, 65).

The polysemic nature of these symbols is also productive in that they can channel different registers of grief, from an internal response to loss, a communal mourning, to a politically charged demand for justice. In creating communities of solidarity, these digital artifacts “in various combinations with other resources, such as text, emoji, and hashtags—afford increased opportunities for identity construction and participation across private and public spheres” ( Giaxoglou and Spilioti 2020, 277). The very pervasiveness of these artifacts—the fact that they can be posted, reposted, retweeted, and replicated across numerous sites—demonstrates their longevity, as well as their inherent power in activating and sedimenting collective memory. In the sections that follow, we outline the methodology we used in identifying and analyzing specific digital artifacts that were circulated in the aftermath of the Quebec Mosque shooting and the Afzaal-Salman murders.

Methodology

In qualitative research, digital ethnography offers tools by which we can understand the situated realities of participants engaged in a social process, as for example, mourning. Moreover, digital ethnography is particularly suited to providing a “thin description” of the occurrence of a given phenomenon. “Thin” descriptions differ from the privileged thick descriptions that are called for in ethnographic research. In thick descriptions, according to Clifford Geertz (1973), the emphasis is on the interpretive protocols that the researcher uses to provide complex analytical insight into the nuances of the cultural ritual or artifact being examined. Geertz’s famous example of the Balinese Cockfight illustrates this kind of rich, close reading and situated textual analysis of the ritual that results in a thick/thickened description. However, as Heather Love (2013, 403) argues, thick descriptions are often preceded by “thin” descriptions, those surface readings that “could be recorded just as well by a camera as by a human agent.” Drawing from the philosopher Ryle’s work, Love further contends that thin descriptions result from, “in effect, taking up the position of the device; by turning oneself into a camera,” and in that sense “one could—at least ideally—pay equal attention to every aspect of a scene that is available to the senses and record it faithfully” ( Love 2013, 407).

Thin descriptions lend themselves very well to digital ethnographies where the possibility of interviewing users poses challenges and where the ethics of lurking on digital sites is problematic. Brekhus et al. (2005) argue that it is the pre-empirical research agenda that determines whether descriptions are thin or thick. Here, we would contend that the research agenda of defining and isolating particular digital artifacts for critical scrutiny demands a thin description that, though anchored to a contextual analysis, remains at a surface level given the very nature of the artifact under consideration. Hence, our methodology is limited in the sense that the analysis offered is not generalizable to all digital artifacts, as for example, the memes and digital caricatures that were circulating in reference to the horrific acts of torture committed at Guantanamo Bay ( Gregory 2006). Nonetheless, we thicken this description by referencing the fact that these artifacts are anchored in a common universe of meaning which recognizes that such expressions and articulations emerge from and in contestation to Islamophobia.

The Hashtag

According to Giaxoglou and Spilioti (2018, 13), “a hashtag can be described as a technomorpheme: it is a linguistic segment as well as a clickable hyperlink, which allows the creation of a network.” Hashtags further organize, archive, and index condensed and layered messages and meanings. Similarly, Andre Brock (2012, 537) posits “Hashtags are folksonomic – situated a priori for users to situate their message within a wider real-time conversation, rather than a posteriori to facilitate retrieval.” Hashtags are thus encoded messages. Bonilla and Rosa (2015, 5) analogize hashtags to library calls, noting that “they locate texts within a specific conversation, allowing for their quick retrieval, while also marking texts as being ‘about’ a specific topic.” Consequently, in searching for digital artifacts of mourning, we began by tracking different hashtags referencing the Quebec Mosque shooting and the Afzaal-Salman murders. In particular, we focused on #RememberJan29, and #QuebecMosqueShooting. For the Afzaal-Salman murders, we focused on the hashtag #OurLondonFamily as it was one of the most visible and frequently used.

In his analysis of Black Twitter hashtags, Sanjay Sharma (2013, 48) observes that “technocultural assemblages”—digital networks, communication platforms, software processes—are constitutive of online racialized subjectivity and activity. Hence, in our search for digital artifacts that were recurrent and posted across platforms, we were keenly aware of the identities of the creators as well as the audiences to whom these artifacts were addressed. Because hashtags tend to draw those users who identify with or are interested in a particular issue, they often generate digital enclaves ( Lim 2020), wherein individuals who share political values or are in solidarity with an issue will post, tweet, or retweet messages to each other.

In following the hashtags, we encountered numerous visual artifacts that were posted by users. Capturing these artifacts demonstrated a range of styles, from screen shots and photographs to graphic drawings of the victims, the surroundings, and symbols like the green flag. In tracing these images, we focused primarily on those that were drawn or created by artists and that were posted across platforms. This gave us an index not only of the popularity of the image but also of its nestedness within different platforms. Using images that were most common across the platform then allowed us to narrow our search to those art forms that aesthetically captured messages of mourning but did so in a way to arouse compassion and sympathy amongst users.

Our methodology then involved tracing these images to their finders/creators, contextualizing them, i.e., thickening the description by situating the images within the context, and then visually analyzing these images. In analyzing the images, we used a combination of Barthian semiotics ( 1973) and visual analysis ( Rose 2001). In the sections that follow, we examine some of the most concurrent images that were in circulation after the tragic deaths of the victims of the Quebec Mosque shootings and members of the Afzaal-Salman family.

Digital Artifacts in the Wake of the Quebec City Mosque Shooting

In 2017, a white Quebecois male stormed into the Centre Culturel Islamique de Québec in Quebec City, killing six men and injuring five others. Immediately after the event, there were multiple vernacular sites set up to commemorate the victims. These included roadside memorials outside the mosque, as well as digital memorials and posts on social media sites ( Jiwani and Al-Rawi 2021; Jiwani and Bernard-Brind’Amour 2022). Figure 2 illustrates photographs of some of these vernacular memorials that were erected after the mosque shooting. That these memorials were captured and circulated in tweets shows how these photos circulate an affect of mourning.

However, even though such photographs document an event and are used to archive it, they do not always go viral, nor are they yoked to campaigns of social justice. In contrast, digital artifacts outlive the moment and tend to trend and circulate long after. In many instances, they become vehicles that are used by various social justice movements and campaigns because they so poignantly capture the affect of grief and mourning and arouse in users a compulsion to “like” and retweet or repost, depending on the platform.

One such digital artifact that circulated after the Quebec Mosque shooting was the following artwork created by Melisse Watson and Syrus Marcus Ware in partnership with the Council of Canadians ( Figure 3). It first surfaced in a hashtag a year after the tragedy in 2018. This image was tweeted and retweeted, posted on Instagram and Facebook and reproduced on numerous newsletters and newspapers. It has become so identified with the event that it is now used to commemorate every anniversary of the tragedy.

Two predominant hashtags, #QuebecMosqueShooting and #RememberJan29, circulated the above image across different platforms. There were numerous other sites and users that reposted and retweeted the image but in tracing their appearance, these two were the most predominant. It is difficult to determine the frequency of these appearances as many of these social networking sites are ephemeral.

We can see in Figure 4 the transfer of this image across different platforms, as for example, in The Suburban, a Montreal newspaper covering the issue of the Quebec Mosque shooting in 2022 ( Wajsman 2022), on BuzzFeed ( Daro 2018), and on various other websites, such as IQRA, the Canadian Muslim Journal’s website ( IQRA 2022). The axis of time through which this digital artifact is iterated references how digital memorials work as points of aggregation, building up micro-histories and keeping collective public memory alive. As Papailias (2016, 442) points out, the commemorative and repeated witnessing (through recall and retrieval) “can make the past continuous with the present.”

Melisse Watson and Syrus Marcus Ware’s painting of the victims of the Quebec Mosque shooting in partnership with the Council of Canadians ( Watson and Ware 2018)

The repetitive use of the image over the time (2018-22) on Twitter. Each of these screen shots is from the different twitter posts that we accessed. For ethical reasons, we do not publish the user names (Twitter 2018-22)

Visual Analysis

In her analysis of visual methodologies, Gillian Rose (2001) makes the argument that one needs to take account of three sites—of production, consumption, and the image itself. She further contends that, at each of these sites, three modalities operate: the technological, compositional, and social. Using a “thin description” approach, we focus on the compositional here and anchor it into the preceding social analysis of Islamophobia.

A visual analysis of this digital artifact necessitates an examination of the origins of this digital artifact. It is evident that portraits of each of the victims were first created by Melisse Watson and Syrus Marcus Ware in partnership with the Council of Canadians. Thereafter, a digitized collage was created by Rachel Small, the journalist who wrote an accompanying article for the Council of Canadians website ( Small 2018). The article underscored the growing Islamophobia in Canadian society and called on readers to participate in the various rallies and vigils that were being organized across the country. Small also referenced a project website #RememberJan29 where individuals could post their messages of condolences, as well as their comments and experiences of Islamophobia.

The collage that Small created used the same stenciled portraits of the victims as designed by the original artists against a white backdrop. However, her composition juxtaposes the faces of the victims in a frame with three faces at the top and three at the bottom, culminating in a visual collage of six faces. The collage serves two critical functions. First, it ruptures the stereotype that all Muslims look alike. The contrasting effect of the faces reflects the diversity of the Muslim victims. The stencil-like effect of the drawings gesture to the victims’ corporeal absence. One’s line of sight is also drawn to the soft blue, taupe, and gray shades that partially highlight the victims’ facial features, giving them a pronounced look that contrasts with the lightness of the stencil that outlines their faces. All the men are smiling or so it seems—reminding the viewers of what they once were in life. This is in sharp contrast to the framing of Muslims as “lethal” ( Dossa 2008), or as untrustworthy “liars” ( Bahdi 2019).

This ties into the second critical aspect of the collage and of the individual portraits. The smiling faces humanize the victims. All the faces look directly at the audience/users. Their gaze appeals to the humanity of the audience. They are not the terrorists so often typified in the mainstream media ( AlSultany 2012; Shaheen 2001); rather, they are the people you meet and see on the streets. Their Muslimness is then made ordinary and non-threatening. This humanization is critical in terms of eliciting compassion and empathy from viewers. It also encourages identification so that different viewers from various ethno-national backgrounds can see themselves as part of the larger community of Muslims and, hence, the murder of these six signifies a loss for each group as well as the larger Muslim ummah.

The victims’ names are written on each of their portraits in a font that is suggestive of handwriting rather than typescript, which makes the writing more informal. This again makes the victims look like ordinary people, and not criminals identified in the news. The font is bolded and its darker appearance contrasts with the thinner lines used in drawing the portraits. Once again, the viewer’s attention is drawn to the names, ostensibly to remind them of the individuality of the victims, as well as to remember those who were killed. The white background of the collage mimics the background used in the original portraits. However, here, it also accomplishes the task of bringing the faces to the forefront, drawing our gaze to the faces rather than to any other aspect of the collage. They stand out, reminding us that they were real even though what we see are the traces of their faces. There are no borders—nothing to separate us from them.

The small composite collage that Small created of these portraits was conducive to its circulation as a digital artifact. It was small, detailed, and aesthetically captivating to be captured and transposed across different platforms. Its reproducibility made it that much more usable and shareable, two features that are integral to enhancing the virality of an image ( Reading 2011).

Giaxoglou and Spilioti (2020) argue that each of these images constitute a form of story-telling. They tell stories about the victims, and in so doing, they ask users/audience to act as witnesses to an act of violence. They incorporate a form of direct address, positioning both the victims and the mourners. These image stories, she adds, “tend to take the form of miniaturized versions of moments and events communicated in textual, visual, audio modes or a combination thereof, making up a narrative as posts accumulate over time and, often, across different social media platforms” ( Giaxoglou and Spilioti 2020, 6). Hence, they form lines of affective alignment that coalesce into a witnessing/mourning assemblage ( Papailias 2016).

Different social networking sites, like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, facilitate the layering of digital artifacts, condensing them with meanings acquired through aggregated posts and references. These then are the micro-stories that Giaxoglou identifies. However, these condensed signs also fuel the generation of other digital artifacts, which cumulatively construct an entire assemblage of mourning. The collage of the portraits of the six victims of the Quebec Mosque shooting gave rise to a whole series of digital artifacts, some created by individuals and others by civil society advocacy groups. Two campaigns that were introduced in the subsequent years after the Quebec Mosque shooting built on the affective alignment of these earlier nodes. These included: #RememberJan29 and the Green Square campaign.

#RememberJan29 and the Green Square Campaign

On January 27, 2018, two McGill University students, Syed Hussan and Aliya Pabani, launched a website, twitter hashtag and an Instagram page commemorating the event. They called it #RememberJan29. Preceding this and immediately after the shooting at the Centre Culturel Islamique de Québec in Ste Foy Quebec, a group by the same name had approached their city councillor in Toronto soliciting his aid in having January 29 officially recognized as a National Day of Remembrance and a call to action to end Islamophobia ( Lee-Shanok 2018). There is no other indication of the identity of the group, and it is not evident if Hussan and Pabani were part of this original group.

Commenting on the anniversary of the Quebec Mosque shooting, Syed posted the following message on his Facebook page ( Figure 5):

It’s January 29th. The two year anniversary of the mass shooting in the Quebec Grand Mosque that left seven Muslim men dead. For months now, Aliya Pabani and I have been struggling with how to mark the moment. We started the hashtag, and website to rage against forgetting, to create space for mourning, to gather together to remember, to reflect and to connect. For over six months, we have tried to ask each other and ourselves - where do we go from there? Have things changed? Does anyone remember? As this morning dawns, I don’t have a clear answer. ( Hussan 2019)

In their analysis of the #RememberJan29 campaign, Jiwani and Bernard-Brind’Amour (2022), outline the genesis and evolution of the campaign and its call to audiences and users alike to assess whether the situation of Muslims had in any way improved, and whether Islamophobia continued to exclude and stigmatize them. Inherent to Hussan and Pabani’s campaign was a critique of the lack of governmental intervention and support for Muslims. In the course of the life of this campaign, Hussan and Pabani continued to update the site with posts detailing news stories and the passage of exclusionary laws, like Québec’s Bill 21, which prohibits Muslim women from wearing the hijab. The hashtag #RememberJan29 was used 14,000 times between 2018 and 2020. However, not all the posts referenced the iconic image of their website.

That same year, in October 2018, on the anniversary of the mosque shooting, the Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East (CJPME) launched their own campaign, discursively resembling the Hussan and Pabani site. Titled “#IRememberJanuary29, it combined a poster, postcard, twitter hashtag, along with a backgrounder info sheet and an email campaign asking political leaders to acknowledge January 29 as a National Day of Commemoration.

CJPME’s campaign, unlike the first digital artifact of the collage of portraits of the victims, uses grief as a platform to make a direct political plea. Further, unlike the collage, here we see individuals holding photographs of the victims in the postcard, and lighting candles in the poster ( Figure 6). The instructions to send an email, send a postcard, and sign a petition explicitly position this campaign in the political sphere. The “I” in the #IRememberJanuary29 is a direct address to the viewer soliciting their identification and empathy with the cause.

CJPME’s campaign was followed by the Islamic Cultural Centre of Québec and the National Council of Canadian Muslims’ Green Square campaign ( National Council of Canadian Muslims 2020). Featuring a green square, where green represents Islam (peace and submission to the will of Allah), the campaign asked individuals to pin a green square to their clothes in remembrance of the victims and to tweet the hashtag and visual. The symbol of the green square has persisted and with each major tragedy, a new message is affixed or overlaid on the square ( Figure 7).

While all of these campaigns served to recall the mosque shooting in the public imagination, they clearly vary in terms of their intended messages and also differ aesthetically. However, they do demonstrate the movement of a collective grief from mourning to a politicized sorrow that could then be harnessed to make a case for a National Day of Recognition and remembrance, and a call to end Islamophobia. On January 29, 2021, the government of Canada finally recognized January 29 as a National Day of Remembrance in honour of the victims of the Quebec Mosque shooting as well as a day to promote action against Islamophobia. To date, the Green Square campaign continues, with the difference that it symbolizes the murders of other Muslims and the persistence of Islamophobia in Canada.

The Afzaal-Salman Murders

In 2021, shortly after the Canadian government’s declaration in remembrance of the victims of the Quebec Mosque shooting, a horrendous tragedy occurred. On June 6, the Afzaal-Salman family went for an evening stroll in their neighborhood in London, Ontario. A 20-year-old white male drove his truck into them, killing four of the five-member family and leaving 9-year-old Fayez Afzaal-Salman as the sole survivor. Fayez was rushed to the hospital with critical injuries. The four who were killed were his parents, his grandmother, and his sister. These murders shook the nation and were widely reported in the national and international media. Immediately after, spontaneous memorial shrines emerged at the site of the attack that killed members of the Afzaal-Salman family ( Figure 8).

Among the most prolific hashtags to emerge was #OurLondonFamily. We tracked this hashtag to find digital artifacts that had outlived the event and that were still in circulation.

One of the most immediate posts of a digital artifact communicating a message of condolence was posted by an artist under the twitter handle @Inkquisitive (see Figure 9). Inkquisitive or Amandeep Singh, who created this graphic art piece, is a well-known artist, who enjoys popularity on Instagram (280,000 followers), Twitter (41,800 followers), and Facebook (139,000 followers) ( “Call Me INKquisitive” 2017). His artwork was accompanied by the following message, “i stand in solidarity with our muslim brothers and sisters mourning the loss of the family massacred in london, ontario.” He added, “another hate crime with a terrorist driving his car into a family, with just 1 of 5 surviving, and that being 9 year old… #islamophobia does exist.” The post ends with two flag emojis—one of the Canadian flag and the other of Pakistan (see Figure 9). On Instagram, the artist posted a long explanation referencing his Muslim friends and their experiences of Islamophobia. He added, “We can’t pretend this does not exist. It’s absolutely devastating to read stories like this. We must stand united against #Islamophobia and all forms of hatred. I stand in solidarity with our Muslim brothers and sisters who are going through similar scenarios and mourning this loss to their respective community. I am deeply sorry” ( Singh 2021).

Spontaneous shrines commemorating the victims of the London attack. Screen shot taken from Twitter post (Twitter 2021)

Inkquisitive’s post and his artwork explicitly reflect how art is used to contest the erasure of Islamophobia. The hashtag #Islamophobia does exist and his statement that “we can’t pretend” otherwise contests the kind of erasure that is endemic to Canadian society’s denial of racism and Islamophobia.

This digital artifact was repeatedly posted on numerous social media platforms (on Reddit, circa June 2021), Wilfrid Laurier University Faculty Association page ( WLUFA 2021), on the Instagram page of a non-for-profit mental health association ( ONTogether 2021), a Facebook recipe page, and on LinkedIn. This is aside from its numerous postings on Twitter. However, it was not the only digital artifact in circulation. There were numerous others, but in the latter cases, while they shared the feeling of abandonment that Inkquisitive’s artwork demonstrates, these other artifacts also expressed alarm and fear about the dangers of Islamophobia.

Figure 10 is headed by a post that begins with “Remember them” and lists the names of the victims. It is this remembering that is political. It is a “remembering otherwise,” which as Hladki argues ( 2014, 79), “means a shift from accounts that reproduce historical experience through normative knowledges to critical reformulations that destabilize those narratives and representations.” The assertion then that Islamophobia exists is then a forceful counter to the myth of a harmonious, multicultural Canada that is devoid of racism.

Visual Analysis

In analyzing Inkquisitive’s image, one immediately recalls the famous 2015 picture of Syrian refugee boy Kurdi lying dead on a beach ( Slovic et al. 2017), a mere child who drowned in the perilous journey to what his parents thought was a safe haven. However, in Inkquisitive’s rendition, the boy in the image is very much alive but perplexed and in grief by the massacre of his family. His hands holding his head communicate a feeling of abandonment, of being left alone to face the world. He clearly represents the sole-surviving 9-year-old Fayaz. The artist’s choice of Fayaz also works to invoke feelings of shared vulnerability.

The sand-coloured background seems to gesture to his ethnic origins, but also surrounds him with warmth. The flowers behind him, at the foot of the pole, signify the memorials that were enacted at the site of the attack and are based on an actual memorial that was erected at the site of the attack. Drawing our attention to the butterflies circulating around the child, Amandeep Singh/Inkquisitive, elaborated in another post on his Twitter account, “four butterflies have come to visit the flowers laid down, the butterflies visiting the young survivor, who is chalking out a moon and heart (instead of a star) reflects on his pakistani background being full of love. It is not a coincidence of the number of butterflies visiting him. With their colours representing the pakistan and canada flag, that too is not a coincidence” (posted June 8, 2021). The crescent chalked out at the child’s feet represents Islam, and the heart that is there speaks to love, as well as compassion and empathy.

The caption on the pole behind the child, “Love for all, hatred for none,” captures the sentiment that was being circulated in the immediate aftermath of the tragedy. It is a plea for a shared humanity and a rejection of Islamophobia. As with the collage of the victims of the Quebec Mosque shooting, the predominant emotion here is one of sadness. However, unlike the collage, the sorrow here is paired with a strong sense of abandonment, gesturing to how Muslims have been abandoned by the state and its apparatuses of power.

The child’s innocence comes through in his gesture of puzzlement and despair, asking implicitly, “Why has this happened to me?” This is indeed the same emotion that rippled through the subsequent posts on Twitter under the hashtag of #OurLondonFamily. Yet, these other posts didn’t so much question why this family, but rather, expressed a shared identification that this could have happened to anyone of us or to our families. The Instagram post in Figure 11 highlights this shared vulnerability and fear.

In Inkquisitive’s graphic art piece, the child’s abandonment then seems to gesture not only to the Muslim communities’ sense of being disavowed by the Canadian state with its denial of Islamophobia, but it also to a perception of how the wider society and the Canadian state views Muslim lives as ungrievable in a global context. The scarce mention and focus on Palestinian lives being lost, of Muslims victimized in India, China, and Russia is a recurrent theme in many of the Twitter posts that we examined. Hence, in the case of #OurLondon family, there is a concerted attempt to make the Afzaal-Salman family members’ lives grievable in the widest possible sense of the term. The discursive move to position the family as “our” London family works to incorporate the victims within the embrace of a larger familial network. It also works to politicize grief so that lives that might have been erased from the public imagination are forcefully brought back into the limelight.

Grief as a Political Resource

Our grieving is bound up with outrage, and outrage in the face of injustice or indeed of unbearable loss has enormous political potential. ( Butler 2009, 39)

In his analysis of the politicization of grief, Leeat Granek (2014) identifies three types of “mourning sickness.” The first deals with the medicalization of grief such that grief is considered to be pathological as it impedes the individual from fully functioning as a productive member of society. The antidote prescribed is that of medications and therapy so that the individual can be disciplined into a docile citizen. In the second type of mourning sickness, the state channels the affect of grief to buttress militarism and nationalism. In the third type of mourning sickness, the affect of grief is activated and directed towards “demanding and instituting positive social change” ( Granek 2014, 66). Granek offers several examples of this kind of activation of grief including the example of the Women in Black in Israel, a non-violent group of women connected worldwide that seeks to protest injustice and militarism ( Women in Black 2022).

Campaign by the Muslim Association of Canada posted on its website ( Muslim Association of Canada 2021) and by the National Council of Canadian Muslims as posted on their Instagram site ( National Council of Canadian Muslims 2021)

In the case of the hashtag, #OurLondonFamily, the visuals that were circulated through the hashtag and cross-posted on other social media platforms generated enough traction to harness the grief, anger, and feelings of exclusion into a movement for social justice. For example, Inkquisitive’s image was subsequently used by the Canadians Against Oppression & Persecution on June 19, 2021 when it posted its call for a Twitter storm, (an increase in the number of posts), on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. The Twitter storm poster identified the related hashtags that users could use to post their messages. The action was in concert with the demands of various civil society groups and individuals calling on the government to convene a national summit on Islamophobia. These included Muslim Association of Canada and the National Council of Canadian Muslims (see Figure 12). On July 22, 2021, the Canadian government finally convened an emergency summit to address the issue of Islamophobia.

Conclusion

What we call memory today is therefore not memory but already history. What we take to be flare-ups of memory are in fact its final consumption in the flames of history. The quest for memory is the search for one’s history. ( Nora 1989, 13)

To remember is a political act as it resists hegemonic power that seeks to suppress subjugated knowledge, rewrite history, and stake claims of innocence. The afterlives of the digital artifacts ensure that histories are not forgotten and that the reality of the perpetual violence of Islamophobia is not evacuated from the public imagination. The very affordances of digital media platforms—their inherent proclivity towards repetition, aggregation, spreadability, and shareability that can be exploited by users—ensures that digital artifacts have afterlives that surpass the moment. However, it is the users’ retrieval, recall, reposting, and retweeting that keeps these artifacts alive.

Every anniversary of the Quebec Mosque shooting, and every anniversary to come of the Afzaal-Salman murders will be remembered through the repetitive invocation of these artifacts. Similarly, every instance of Islamophobic violence will be coupled with these artifacts so that they keep memories alive and propel the struggle for social change. These digital artifacts are productive insofar as they demonstrate how the affect of grief can and has been channeled into struggles for social change and demands for equity. The aesthetic quality of many of these digital artifacts also make them appealing to different audiences, invoking in the process, empathy, compassion, and community. They embody the stories of the communities involved, keeping alive the networks of sociality and documenting the struggles that are encountered.

In conclusion, digital artifacts don’t operate independently, nor are they agentless artifacts floating in the virtual worlds of the internet. It is the concerted effort of communities, individuals, and civil society groups that activate these artifacts, keeping them alive and contributing to their circulation through the various nodes of grief and collective mourning. Ultimately, it is the activist power of civil society that drives digital artifacts in terms of their use and reuse, and that encodes them with layers of meaning. Archiving these artifacts represents one step towards recuperating and sustaining our collective history of our struggles to contest, counter, and ultimately eradicate Islamophobia.