1. Introduction: Human Rights, Indigenous languages, and the Politics of fear in the United Nations’ International Decade of Indigenous Languages

Extensive research and long-term experience show that human rights activism can be effective in motivating states to change their behavior: to cease committing human rights violations or lessen their severity (Franklin 2008; Krain 2012; Murdie and Davis 2012; Becker 2013; Hendrix and Wong 2013; Terman and Voeten 2018). However, research also shows that states can shut down human rights activism and undertake other measures to grant themselves impunity, enabling them to escape accountability and continue committing human rights violations (Bakke et al. 2020; Smidt et al. 2021; Cronin-Furman 2022). In this article, we explore the relationship between human rights activism and states’ efforts to suppress it, in connection to the United Nations’ International Decade of Indigenous Languages (UNESCO 2021). We focus on three countries in Asia—China, India, and Indonesia—and on how crackdowns on human rights activism and civil society are likely to hamper efforts to implement the Decade in these countries.

The United Nations’ International Decade of Indigenous Languages was organized in recognition of the persistent and drastic threats that Indigenous languages face around the world today. According to the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (2018), of the approximately 7,000 languages spoken today, around 4,000 are spoken by Indigenous people, and almost all of these are considered “endangered”. Whereas the UN advances the neutral, technocratic framing of language endangerment in its documents, we use terminology that explicitly highlights the deeply political nature of this issue, and therefore adopt the term “language oppression” from Taff et al. (2018: 863), who define it as the “enforcement of language loss by physical, mental, social, and spiritual coercion” (emphasis in original).

Language oppression is a significant issue because it harms Indigenous people in substantial ways, and resisting it is therefore important within broader agendas aimed at liberation and decolonization. When communities are coerced into giving up a language, individuals and communities are harmed through loss of culture, erosion of identity, and the breakdown of kinship and other social relations (Meek 2011; Wyman 2012; Couzens et al. 2014). Individuals who experience language oppression and its intergenerational impacts also experience emotional and psychological suffering (Bostock 1997; Olko et al. 2022; Hammine and Zlalzi forthcoming), decreased health and well-being (Taff et al. 2018), and increased exposure to premature death (Roche 2022). Our intervention in this article is part of broader efforts to reduce these harms by supporting individuals and communities to reclaim their languages, by critiquing, exposing, and opposing dominant actors that engage in language oppression. Although we recognize that language oppression can be carried out by transnational articulations of powerful actors (Roche 2019), we also acknowledge that the state is the primary agent of language oppression today; it is in recognition of this that we place our work within wider conversations about state crime.

Therefore, although we are deeply supportive of the broader goal to “preserve, revitalize, and promote Indigenous languages” (UNESCO 2021), we are sceptical as to whether this can be achieved under the auspices of the United Nations, for two reasons. The first reason is that we concur with authors such as Churchill (1997, 2003) and Kuper (1981) in seeing the UN primarily as an institution designed to secure and defend state interests, over and against those of minorities and Indigenous people. Secondly, as we intend to demonstrate in this article, we believe that the current plans for the International Decade of Indigenous Languages have flaws that create serious barriers to successful implementation of the Decade.

A central focus of the planning and implementation documents for the International Decade of Indigenous Languages is a human rights approach. This focus connects the Decade to ongoing academic debates about languages and human rights (Skutnabb-Kangas and Phillipson 2023), including such issues as the relationship between language and fundamental rights (de Varennes 2001), the existence of group rights in relation to language, and the place of language rights within the broader suite of so-called “third generation” rights (May 2011). It also connects the Decade to long-standing practices of language rights advocacy and activism, both inside and outside the UN. Most directly, however, the Decade draws on language rights as put forward in the UN’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP 2007). These include:

The right to revitalize, use, develop, and transmit Indigenous languages to future generations;

The right to establish, control, and access educational systems and institutions in Indigenous languages; and

The right to establish media in Indigenous languages.

The approach put forward in the plans for the Decade also emphasizes the links between language rights and the human rights and fundamental freedoms enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, including freedom of thought, opinion, and expression, and rights to education, health, information, and work.

Beyond this focus on human rights, the plans for the Decade also emphasize that Indigenous people should take a leading role in implementing the Decade. This approach is based on the principle of “nothing for us without us” (UNESCO 2020) and, in recognizing this, the Decade has adopted the motto, “[l]eaving no one behind, no one outside” (UNESCO 2021). When combined with the human rights focus outlined above, this approach suggests that the Decade’s plan to protect, promote, and revitalize Indigenous languages requires Indigenous people around the world to build an active, interconnected civil society sector in defence of their language rights and other human rights.

In this article, we document how this framework places Indigenous people at risk, due to rising attacks on human rights defenders and growing restrictions on civil society. Indicative of the situation detailed below in our case studies, we note that in 2021, 26 per cent of rights defenders that were killed globally were Indigenous people (Front Line Defenders 2021), despite the fact that Indigenous people represent only 6 per cent of the global population. We argue that, although these attacks and restrictions do not explicitly target Indigenous people engaged in language activism, they nonetheless will contribute to a generalized politics of fear that suppresses Indigenous language activism, often before it even begins.

The concept of the “politics of fear” that we use here is taken from the work of sociologist Guzel Yusupova (2022), who explores how in Russia policy changes regarding minority languages have worked to demobilize and reshape language activism. In our application of this idea, we extend Yusupova’s work by combining it with literature on the suppression of human rights activism and state terrorism to argue that, beyond demobilizing and reshaping activism, the politics of fear can also be effective in preventing activism. Before we get to the substantive case studies that we use to demonstrate this point, we first turn to issues of methodology that inform our work.

2. Methodology

Our article examines the relationship between the state, human rights activists, and Indigenous languages, with a special geographical focus on Asia. This focus recognizes that Asia is the most linguistically diverse continent on earth (Roche and Suzuki 2018), and also that discussions of global indigeneity typically tend to focus on Anglophone settler contexts (Merlan 2009) to the exclusion of Asian Indigenous people and their struggles. Mindful of the complexities relating to Indigeneity and post-coloniality in Asia (Kingsbury 1998; Robbins 2015), we think it is imperative for any discussion of global Indigenous politics and languages to take Asian contexts seriously.

Having noted this, we also think it would be unfeasible to try and provide a general overview of Asia in its entirety. Instead, we present three case studies: China, India, and Indonesia. These three countries are the most populous in the region, and also the most linguistically diverse. What happens in China, India, and Indonesia affects almost 40 per cent of the global population and 20 per cent of its languages, and therefore understanding the state crimes of these countries has particular global significance.

For each case study, we provide general background information about the situation of Indigenous languages, and an overview of recent restrictions on civil society and human rights. The background on languages is drawn from linguistic reference works, including Cataloging the World’s Endangered Languages (Campbell and Belew 2018), Encyclopedia of the World’s Endangered Languages (Mosely 2010), and the Ethnologue (Eberhard et al. 2022). Our discussion of attacks on human rights defenders and restrictions on civil society mostly focus on the period since 2019, as this was the year when the intention to launch a Decade of Indigenous Languages was announced. The information that we present in this regard is based on the reports of several non-governmental organizations, including Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, Frontline Defenders, Article 19, and Civicus Monitor. 1 We also draw on relevant academic literature and our own research experience in these countries (see below).

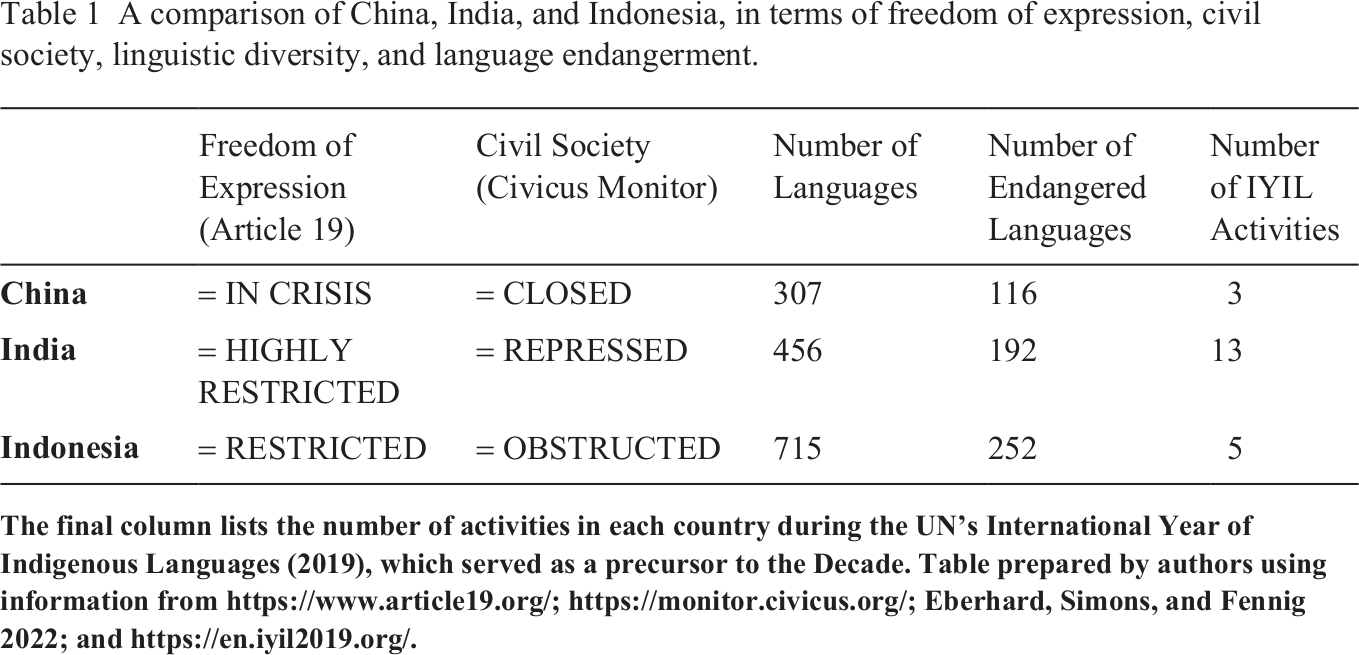

As a general way of situating the case studies relative to each other, Table 1 provides information about human rights and civil society in each country, as well as a brief linguistic overview. Very broadly, this table shows that, in addition to providing coverage of a large number of languages and people, our selection of cases also covers a sequence of political contexts that ranges from severely repressive (China) to relatively open (Indonesia).

A comparison of China, India, and Indonesia, in terms of freedom of expression, civil society, linguistic diversity, and language endangerment.

The final column lists the number of activities in each country during the UN’s International Year of Indigenous Languages (2019), which served as a precursor to the Decade. Table prepared by authors using information from https://www.article19.org/; https://monitor.civicus.org/; Eberhard, Simons, and Fennig 2022; and https://en.iyil2019.org/.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge the issue of authorship of this article. According to the principles of the UN’s Decade, and the broader principle of Indigenous self-determination, this article would have ideally been authored by, or at least in collaboration with, Indigenous people from China, India, and Indonesia. However, this is not the case. Both Gerald Roche and Jess Kruk are non-Indigenous people of European descent living in present-day Australia. Gerald lives on the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation, and has undertaken research in China, while Jess lives on unceded Nyungar boodjar and has done research in Indonesia. Madoka is an Indigenous Ryukyuan (Okinawan/Yaeyaman) scholar who lives on the island of Okinawa, where traditional cultures and lands continue to be threatened by the denial of Indigenous rights to self-determination and prior informed consent in policymaking. Jesus Federico Tuting Hernandez is a native speaker of Central Bikol, one of the Indigenous languages spoken in the Bikol region of the Philippines.

Our decisions about the authorship of this article were made in response to the political contexts presented in the case studies below. With increasing attacks on human rights defenders and restrictions on civil society in China, India, and Indonesia, we felt that including Indigenous people from these countries would place them at risk. This highlights a broader ethical bind in discussing Indigenous language issues in contexts where human rights defenders are under attack. If we respect the principle of Indigenous participation, we place Indigenous people at risk, but if we prioritize the safety of Indigenous people, we contravene the principles of Indigenous participation and self-determination. There is no good solution to this problem, but we have opted to prioritize safety, in response to the alarming developments we outline in the following case studies.

3. Case studies

3.1. China

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is home to over 300 languages; over one-third of them are considered endangered. Eberhard, Simons, and Fennig (2022) report 30 languages to be nearly “extinct”.

In addition to the Han Chinese majority, the PRC’s government divides the country’s population into 55 minority nationalities, each of which is formally considered to have a single language (Roche 2019). The majority of the country’s languages are not recognized as being the designated language of a nationality, and are thus considered “dialects”: a term with multivalent meanings and a complex history in the Chinese context (Tam 2020). However, it should be noted that the label “dialect” here is not a linguistic categorization, i.e. a variant of a language, but a devaluation of the linguistic status and identity of various ethnolinguistic groups that are not classified by the government within the minority nationalities. It is a label that demotes and delegitimizes the linguistic status and the cultural standing of these ethnolinguistic groups which results in the denial of the rights of people who speak these so-called dialects.

The PRC’s government also refuses to recognize the existence of Indigenous peoples in the country (Elliot 2015; Hathaway 2016). By not acknowledging the presence of Indigenous peoples, it denies all Indigenous people’s rights recognized by the United Nations (Anonymous 2019). The refusal to acknowledge the languages and indigeneity of the majority of the ethnolinguistic groups in the country has led to a gradual erasure of the diversity of the languages, cultures, and peoples of China.

This destruction of diversity is accomplished in various institutions of government, but particularly in the educational system. In 2020, Mandarin Chinese language and literature took the place of Mongolian language and literature in lessons taught in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. The opportunities for Mongolian language teaching were noticeably reduced. Despite opposition to this attack on the Mongolian language and culture, which resulted in eight suicides (Bulag 2020), authorities carried out the plan. This disregard for the right to be educated in one’s own language also saw the reversal of the State Council’s Child Development in China (2021–2023) policy, which was committed to respecting and defending minority children’s right to receive education in their language (Grey and Baioud 2021). The plan mandated that preschoolers begin studying Mandarin before primary school. Mandarin was also required in kindergartens in underserved and rural areas starting from the autumn of 2021, according to the Ministry of Education’s most recent Five-Year Plan (2021–2025).

The implementation of education for Tibetans demonstrates this system in practice. Currently, the PRC’s government extends limited and declining support for Tibetans to use a single Tibetan language in public institutions like education (Roche 2019, 2023). However, Tibetans are a highly multilingual population, speaking around 30 different languages in addition to Tibetan (Roche and Suzuki 2018). The government refuses to recognize these languages, and excludes their use in public institutions such as schools, media, healthcare, and other public forums. Community-led efforts to introduce these languages into public institutions are actively suppressed. The outcome of over half a century of such practices has been widespread decline in intergenerational transmission of Tibetan languages.

Meanwhile, since 2017, the primary school curriculum in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region has shifted to a Mandarin-only model, with minority languages being taught only as an occasional subject. Even while Uyghur is still a spoken language and can still be seen in public on signs, the conditions that allow it to be passed on to new generations have been steadily deteriorating. At around the same time when these significant changes were introduced to the education system, the mass internment system in Xinjiang began serving as a tool for enforcing the learning and use of Mandarin. Testimonies from the camps reveal that languages other than Mandarin are often forbidden, and inmates are punished with physical violence for using them (Byler 2022; Ayup et al. 2023). This coercive assimilatory strategy aims to erode the languages and identities of minority nationalities through fear and violence.

Protesting linguistic impositions and advocating for minority languages in the PRC has led to unjust imprisonment under charges such as “incitement to separatism” (Roche 2021). Protest leaders are often recipients of draconian state retaliatory measures. For example, Tibetan language advocate Tashi Wangchuk was found guilty under this charge and was sentenced to five years in prison after participating in a documentary film, “A Tibetan’s Journey for Justice” in which he appealed for education in the Tibetan minority language (Kessel 2015). Apart from unjust and unfounded incarceration, protesters and human rights advocates are also subject to forced disappearances and secret trials, often resulting in isolation, torture, and imprisonment. Families of the disappeared are harassed, surveilled, and subjected to various sanctions that negatively impact employment and access to services.

International human rights organizations continuously monitor and report on various violations of civil liberties in the PRC. In terms of freedom of expression, Article 19 now classifies the PRC as being “in crisis” (Article 19 2022). Human Rights Watch’s 2021 report describes how Tibetans are still subjected to grave human rights abuses, and how Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang are subject to mass detention and torture for exercising their fundamental rights. Various reports agree that human rights violations in Xinjiang remain particularly extreme, and include detention, torture, sexual and gender-based violence, separation of children, and severe restrictions on the expression and practice of culture, among others.

During its 101st session in 2020, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination expressed concern over the PRC’s continuing persecution of language rights advocates. Concern was also expressed regarding government restrictions on the use and teaching of minority languages (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights 2020). The PRC denied these claims.

Finally, the reach of the repressive arm of the PRC goes beyond its borders. Protesters and critics abroad have reported being surveilled, threatened, and harassed. At the same time, global rights organizations are often denied access to information, making it difficult to assess the full situation of the threatened communities in China, and even more difficult to create connections with its Indigenous peoples and communities.

3.2. India

Home to over 1.3 billion people, India is one of the most highly multilingual countries in the world. With over 450 languages, it is estimated to be the fourth-most linguistically diverse country in the world (Eberhard et al. 2022); over 40 per cent of the country’s languages are considered endangered (Campbell and Belew 2018; Mosely 2010).

India is home to about 104 million Indigenous peoples: almost 90 per cent are rural (Sapriina and Chakma 2019). Indigenous people in India face numerous challenges, including massive displacement due to development projects, and alarmingly high levels of violent hate crimes at the hands of state security forces (Pal 2019). Indigenous groups in India have historically been marginalized and exploited by the state (Sundar 2011). Meanwhile, the application of the concept of indigeneity in India remains contested at various levels of government, and also within some sectors of civil society (Xaxa 1999a, 1999b).

Giving a simple figure of the number of languages in India is difficult. The 2001 Census of India reported 122 languages (Groff 2017), while 450 languages were recognized by Ethnologue (Eberhard et al. 2022). However, official estimates of India’s linguistic diversity, such as the national census, systematically under-represent the number of languages by reclassifying distinct languages as dialects (Abbi 1995; Mohanty et al. 2010). Furthermore, even those languages that are recognized are treated unequally. In 1995, 18 languages were officially recognized in Article 343–51 of the Government of India’s Constitution (Abbi 1995; Boruah 2020). At present, 22 are formally listed in the Constitution (Groff 2017). These languages, as well as “classical” languages, are given extra support by the state, whereas smaller languages are neglected, creating enormous inequalities between various levels of India’s linguistic hierarchy (Babu 2017). And, despite some partial, localized success in supporting Indigenous languages in India (Mohanty 2023), violations of Indigenous language rights in key areas such as education remain far more common (Rao 2019), indicative of a broader language rights framework that is promising on paper but deeply exclusionary in practice (Nag 2023).

In 2022, Civicus Monitor added India to their watchlist of countries of serious concern, alongside Russia, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, El Salvador, and Kazakhstan (Civicus Monitor 2022a). Although the country has been classified by Civicus Monitor as “repressed” since 2019, ongoing detention of human rights defenders, new raids on NGO offices, and attacks on journalists all earned India a place on the watchlist in 2022.

The situation for human rights defenders and civil society in India has been in steep decline since the election of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in 2014, and the implementation of their project of xenophobic cultural nationalism (Leidig 2020). Since being re-elected in 2019, the BJP under Narendra Modi has intensified their crackdowns on and ongoing conflict with Indigenous peoples. Human rights defenders and civil society, both in general and in relation to Indigenous people, are increasingly targeted by legal suppressions. These include the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, which allows the state to target individuals and organizations for terrorism and sedition, and the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, which enables the state to restrict access to foreign funds for NGOs. Since 2019, the Indian state has repeatedly used both legal and extralegal measures to target Indigenous people and their allies, and to suppress civil society more generally.

In 2019—the UN Year of Indigenous Languages—state security forces put down an Indigenous uprising in the state of Jharkhand, known as the Pathalgadi movement, arresting thousands of Indigenous people (Chakma and Martemjen 2020). Examples of more targeted violence against Indigenous people included the 23 January detention and torture of four Indigenous teenagers in Madhya Pradesh, the 27 August death by torture of Pappu Bheel in Rajasthan, and violent police attack in July on Chhara communities in Ahmedabad city. Meanwhile, over a million forest-dwelling Indigenous people were threatened with evictions by new conservation laws (Chakma and Martemjen 2020).

Civil space more broadly continued to deteriorate after the BJP government was re-elected in 2019. The special constitutional status of the Jammu and Kashmir region was revoked, leading to protests that were violently suppressed, coupled with an internet blackout that went on for 18 months. Meanwhile, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act was updated to enable the state to designate individuals as terrorists. Finally, in August, the state of Assam released a National Registry of Citizens, creating what UN Special Rapporteur on Minority Issues Fernand de Varennes referred to as “the biggest exercise in statelessness since the Second World War” (Ratcliffe 2019). Amongst the nearly 2 million people rendered stateless by the registry were some 100,000 Indigenous people (IWGIA 2020a).

In 2020, attacks on Indigenous people continued. Eleven Indigenous Gond people were killed in July in the state of Uttar Pradesh whilst defending against a land grab, and in October an Indigenous land defender was attacked and beaten, later dying in hospital in the state of Tripura, northeastern India. Forced evictions of Indigenous people continued. For example, in April, 32 families in Sagda village in Odisha state were evicted on the grounds that they were encroaching on reserved forest land (Land Conflict Watch 2020), and in December, 100 families of Chakma people were forcibly evicted from their homes in Mizoram state (Chakma and Martemjen 2020). Government statistics from this year showed that crimes against Indigenous people rose by 9.3 per cent (Jyoti 2021).

In addition to these attacks on individuals and communities, the state continued to intensify its attacks on Indigenous land in the name of development. As part of the government’s COVID recovery plan, 38 plots of land were auctioned to coal mining companies—mostly Indigenous lands in the states of Jharkhand, Maharashtra, and Odisha (IWGIA 2020b). The coal mines are mostly located in the forests upon which the livelihoods of Indigenous people depend. Meanwhile, the updated Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act was used to arrest human rights defenders, including Indigenous rights activist Father Stan Swamy (who later died in prison), Indigenous rights defender and language policy scholar Hany Babu (still detained), and journalist and rights activist Gautam Navlakha (still detained). The Foreign Contributions (Regulation) Act was also amended to prevent large NGOs from distributing funds to grassroots groups. Almost immediately the new act was put into practice to freeze the accounts of Amnesty International.

These attacks on civil society and human rights defenders continued in 2021. Some ten NGOs were also targeted by the Foreign Contributions (Regulation) Act. Furthermore, Aakar Patel, Chair of Amnesty India, was arrested and charged for social media posts. Climate activist Disha Ravi was arrested for sedition and “spreading disharmony”. The home and office of activist Harsh Mander were raided in Delhi, and Indigenous activist Hidme Markam was arrested.

3.3. Indonesia

Indonesia is home to over 1,300 communities speaking more than 700 languages, located across at least 17,500 islands, making the nation one of the premier sources of cultural and linguistic diversity in the world (Badan Pusat Statistik Indonesia 2010). However, according to Ethnologue, approximately 35 per cent of Indonesia’s languages are classified as endangered (Eberhard et al. 2022), many of which are found in the region of West Papua, which forms the focus of this section.

Located in the western part of the island of New Guinea, West Papua was forcefully annexed from the Netherlands by Indonesia in 1969. In an attempt to quell growing separatist demands, the Indonesian government issued a Special Autonomy Law for the region, after which the government divided Papua and West Papua into two separate provinces (Resosudarmo et al. 2014). In 2022, the region was further divided into five provinces, namely Papua, Highland Papua, Central Papua, South Papua, and West Papua. In contrast, the Indigenous people of the region recognize seven distinct areas of culture, which include Tabi, Saireri, Domberai, and Bomberai along the north coast (Flassy 2019). The Me-Pago and Lani-Pago territory are located in the highlands of Papua and Ha-Anim territory is located on the south coast of Papua (Flassy 2019).

Indigenous Papuan people have inhabited the region for at least 42,000 years (Gillespie 2002). However, more than half of the present population are transmigrants who arrived through the government programmes between the 1970s and early 2000s that incentivized Indonesians from densely populated provinces (such as Java and Madura) to settle in more sparsely populated provinces (including West Papua) (Anderson 2015). As such, the region boasts the highest levels of cultural and linguistic diversity in Indonesia, with 274 living languages documented in the West Papuan province alone (International Coalition for Papua (ICP) 2020).

Far from supporting linguistic diversity in the region, the Indonesian government has used transmigration to support their larger project of cultural assimilation. Though Indonesia’s language politics are shaped by the national ideology of Bhinneka Tunggal Ika “unity in diversity”, government policies have strongly emphasized unity over diversity (Arka 2013; Coleman and Fero 2023). Forceful Indonesianization began under President Suharto in 1966, and today persists in the form of various government policies, perhaps most notably in the educational model. Since the 1940s, education across Indonesia has been primarily delivered in Bahasa Indonesia, the national language and state-sponsored lingua franca (Abas 1987). Until the mid-20th century, local languages were included in the educational system, but when Suharto’s unitary model of education was implemented in 1966–1990, only a limited number of major Bahasa Daerah “regional languages” retained a limited position in the state curriculum (Dardjowidjojo 1998). Consequently, the vast majority of Indigenous people, including those in West Papua, are taught exclusively through a single standardized form of Indonesian.

In May 2013, the Constitutional Court of Indonesia affirmed the Constitutional Rights of Indigenous Peoples to their land and territories, including their collective rights to customary forests (Johnson 2013). Additionally, Indonesia is also a signatory to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) which establishes a framework for minimum standards for human rights and fundamental freedoms afforded to Indigenous peoples, including their right to establish and control their educational systems and institutions providing education in their own languages (UNDRIP 2007). Despite this, Indonesian governance in West Papua has been consistently indifferent to the views and interests of its Indigenous people (Anderson 2015). This indifference is frequently justified by government officials who argue that all Indonesians, except those considered to be of foreign descent (in particular, Chinese Indonesians; Setijadi 2019), are Indigenous, and thus entitled to identical rights (Suryadinata 2017). On this basis, the Indonesian government has consistently rejected calls to address the needs of specific groups identifying as Indigenous to particular regions.

Beyond ignoring Indigenous peoples, the Indonesian government has actively oppressed West Papuans through severe restrictions placed on civil liberties, including arbitrary detention for months or even years, restricted movement (often under the guise of security concerns), restrictions on freedom of speech and assembly, and requirement that people obtain a Surat Jalan (travel permit) before travelling to their villages (Anderson 2015; Wing and King 2005). Since the election of President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) in 2014, and concurrent decline of Indonesian democracy (Aspinall and Meitzner 2019; Tomsa 2022), incidents of violence against Indigenous peoples in West Papua have grown; since the start of Jokowi’s second term in 2019, there has been an increase in the number of criminalization cases, along with the government’s investment-first agenda (Siringoringo and Mambor 2020). Among these, acts of violence and criminalization against Indigenous peoples and Indigenous human rights defenders continued to occur. In 2019, more than 15 cases of land grabbing, arrests, violence, and evictions took place targeting Indigenous communities (Siringoringo and Mambor 2020).

To better understand the nature of state violence against Indigenous peoples in West Papua, we focus on three incidents from recent years. The first occurred in December 2018, when an armed wing of Organisasi Papua Merdeka “Free Papua Movement”, Tentara Pembebasan Nasional Papua Barat (TPN-PB) “National Liberation Army of West Papua” kidnapped and later executed 16 workers from a state infrastructure construction site (Wangge and Webb-Gannon 2020). In response, the Indonesian government launched a military campaign, causing the displacement of tens of thousands of people. Local civil society organization, the Nduga Solidarity Civil Society Coalition, reported that 182 civilians died as a result of the conflict and subsequent displacement (RNZ 2019). The second incident occurred in August 2019, when Papuan students protesting in the city of Surabaya (East Java) were attacked by civilian militias, insulted with racist slurs, and then arrested (Saud and Ashfaq 2022). This incident incited widespread protests throughout West Papua, which were violently suppressed by police and Human Rights Watch reported 33 people were killed (HRW 2019). These incidents highlight disproportionate attacks from the state in response to perceived threat posed by West Papuan Indigenous people. Importantly, violent attacks on West Papuans are accompanied by malicious neglect by the state. For example, a measles outbreak in Asmat regency killed an estimated 100 Papuan children in January 2018, after these children had been excluded from national vaccination programs (Harsono 2018).

Ultimately, the Indonesian government has consistently pursued a fundamental policy of violently retaining Papuan territories and forcefully assimilating Papuan people. Over the past five years, violence and armed conflict in Papua have intensified: thousands of Indigenous Papuans have been arrested and hundreds imprisoned, while dozens have been killed. Simultaneously, government migration programs have seen the non-Indigenous population in West Papua steadily growing, further marginalizing Indigenous Papuans in their own lands. In effect, under Indonesian colonialism in West Papua, Indigenous people are threatened with losing not only their territory, but also their way of life, their traditions, languages, and identities that have been passed down from generation to generation.

4. Conclusions

In 2019, the United Nations announced its intention to hold an International Decade of Indigenous Languages starting in 2022, in order to “preserve, revitalize, and promote” Indigenous languages (UNESCO 2021). They have since promoted plans for the Decade that encourage the active participation of Indigenous people in human rights activism to achieve these goals. In the years that have followed this announcement, the three most populous and linguistically diverse countries in Asia—China, India, and Indonesia—have witnessed intensifying crackdowns on civil society and attacks on human rights defenders. These are taking place in contexts where Indigenous rights are not substantively recognized, and in which linguistic diversity has long been under attack by assimilatory states.

We argue that this conjuncture of increased state oppression in China, India, and Indonesia, and the promotion of transnational Indigenous rights activism by the UN, is setting up Indigenous people in these countries for failure, if not something much worse. Despite the fact that variation exists between and within these states regarding how, and how well, they manage their Indigenous languages, they all broadly represent an unjust, and worsening, status quo that must be radically altered in order for Indigenous languages to be “preserved, revitalized, and promoted”. The UN’s framework for the Decade suggests that this radical change should be brought about through human rights activism by Indigenous people themselves. The trends we have described here suggest that China, India, and Indonesia will not allow this to happen.

Returning to the literature introduced at the start of this article, on successful state repression of human rights activism (Bakke et al. 2020; Smidt et al. 2021; Cronin-Furman 2022), we argue that whatever successful language rights activism Indigenous people in these countries do engage in as part of the Decade, these states will be able to effectively suppress. Beyond simply having the capacity to suppress such activism, given the trends we have described above, we believe that these states are also likely to do so. Bakke et al. (2020), for example, show that states can successfully suppress human rights activism by engaging in a range of different measures, including: banning specific civil society organizations; curtailing travel; restricting visits to government sites; limiting domestic and international funding sources; creating difficulties in obtaining visas or denying visas; creating difficulties in registering as civil society organizations; censoring publications; harassing civil society activists; and surveilling civil society activists. We have reported examples of most of these activities in the case studies above; there is no reason to think that Indigenous language rights activists and organizations will somehow be spared from the ongoing and intensifying crackdowns in these countries in the coming decade.

In addition, we argue that, beyond the state’s capacity to successfully suppress any Indigenous language rights activism that might emerge during the Decade, the restrictions on civil society and attacks on human rights activists in these countries will also decrease the chances that new organizations and forms of activism will emerge to support Indigenous languages. In making this argument, we draw on and expand Guzel Yusupova’s (2022) arguments about the politics of fear and minority language mobilization in Russia. Yusupova highlights how repression can demobilize and transform minority language activism, for example by leading activists to present language as a cultural, rather than political, issue. We extend this by arguing that such a climate of fear, resulting from public attacks on activists, can also prevent new forms of activism from emerging. Therefore, although the attacks on activists and organizations we have described have not explicitly targeted Indigenous language rights activists, we expect that they will nonetheless have a chilling effect on language activism. We see this effect on language activism as being part of broader, and well-known, patterns of state terrorism and governance by fear (Taussig 1984, 1989; Green 1999; Elden 2009).

So, although we have focused on China, India, and Indonesia in this article, we consider the dynamics that we have described to be broadly applicable to a variety of contexts across Asia (and elsewhere). For example, in the Philippines, state-sponsored attacks on human rights activists, including killings, and suppression of civil society organizations drastically increased during the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte (2016–2022), often through the practice of so-called “red-tagging” (maliciously labelling individuals and organizations as terrorists: Simangan 2018; Hapal et al. 2022; Iglesias 2022). In Uzbekistan, transnational civil society has been heavily restricted since the government violently suppressed protests in the city of Andijan in 2005 (Carothers and Brechenmacher 2014; Cronin-Furman 2022). In Afghanistan, the Taliban government has, since returning to power in 2021, effectively dismantled civil society, while attacking a range of human rights activists. In Bangladesh, crackdowns on human rights organizations and activists have intensified since 2018 (Civicus Monitor 2022b), and the proposed “Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission Regulation for Digital, Social Media and OTT Platforms” threatens to further restrict freedom of expression in the country and beyond its borders (Lita 2022). And in Mongolia, new laws proposed in 2021 threaten to severely curtail the country’s civil society (Civicus Monitor 2022c).

Across the world’s most linguistically diverse continent, therefore, the prospects are grim for a successful and safe International Decade of Indigenous Languages based on human rights activism by Indigenous people. In this context, we suggest that the International Decade of Indigenous Languages requires effective measures to limit state power, including an end to impunity for state attacks on human rights defenders and Indigenous people. Although the UN’s goal of centering Indigenous participation in the Decade is laudable, it is currently not linked to any mechanisms that would ensure the safety of Indigenous people who decide to heed this call.

Within the UN, various options do exist to support and protect grassroots Indigenous language activists. These include the office of the Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders, which could specifically monitor and produce information about the situation of Indigenous language rights defenders in relation to the Decade. Measures such as this, and broader involvement of the UN’s human rights offices, would also help make an important shift in how the Decade is perceived and implemented: from a celebratory cultural event under the auspices of UNESCO, to a human rights campaign entailing serious risks for participants, and thus requiring broader integration across the UN and much greater scrutiny of— and restraint on—governments.

Outside the UN, grassroots solidarities between Indigenous peoples could also help counter state power and support Indigenous language rights activism. In her discussion of the politics of fear and minority language mobilization, Yusupova (2022) discusses the importance of online connective action as a conduit for solidarity that counteracts the politics of fear, helps circulate activist strategies and techniques, and fosters offline activism. We believe that in order to effectively promote safe and effective language activism by Indigenous activists during the Decade, such connective action, and the solidarity it creates, should explicitly focus on spreading information about how states govern through fear and terror, the strategies they use to suppress activism, and actions that activists can take to safely subvert and circumvent these tools of state power.