Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic arrived in Europe in early 2020 at a moment when labour markets were already in a process of rapid transformation, with a sharp growth in the ‘platformisation’ of work (Huws, Spencer & Coates, 2019). This represented the continuation of a trend that began in California in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, arrived in Europe around 2012–2013 and appeared to be approaching critical mass by the end of the decade (Pesole et al., 2018; Poon, 2019; Urzi Brancati, Pesole & Fernandez Macias, 2020).

As countries went into lockdown, there was a major growth in working from home, with an estimated one-third of the European workforce taking up teleworking as a result of the pandemic (Eurofound, 2020) and, with it, a surge in demand for home deliveries of groceries, ready meals and other items. Simultaneously, however, there was a sharp drop in demand for transport and tourism-related services (see for example Faus, 2020) – all sectors where online platforms were active. The first trend implied an increase in platform work; the second, a decrease. What was the reality? Perhaps even more important than quantitative trends were qualitative ones. What was the impact of the pandemic on the working lives of platform workers?

This article draws on two important bodies of research, one quantitative and one qualitative, to gain a rounded view of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lives of platform workers in one European city: London. In bringing together these two sources of data, it enables an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon which neither source, taken alone, could capture, making it possible to understand the causes of trends that would otherwise remain unexplained. The first source it draws on is a series of surveys, carried out by the University of Hertfordshire, looking at the extent and nature of platform work. Surveys had already been carried out in the UK in 2016 and 2019, providing a historical picture of the growth of platform work, and it was possible to repeat the same questions in a further survey in England and Wales in 2021 to explore the changes that took place between 2019 and 2021 – the period in which COVID-19 took hold. 1 The second source was a series of interviews and focus groups with platform workers involved in driving and delivery work in London carried out in 2019 and 2020 as part of the PLUS (Platform Labour in Urban Spaces) research project. 2 London represents the largest concentration of platform work in Europe (Keown & Saigol, 2020) and is thus of particular importance for scholars in the field more generally.

Previous analyses of the survey data (Huws, Spencer & Coates, 2019; Spencer & Huws, 2021) have focused on broad patterns of changes in platform work. This article adds to this knowledge by concentrating on sub-national trends and exploring the specific effects of the pandemic. Likewise, previous reporting on the interview data (Benvegnù & Kambouri, 2021; Kambouri & Walsh, 2022) analysed the place of platform work in an urban setting in a comparative European context. Here, as well as looking in particular at issues relating to the pandemic, it is possible to introduce a historical perspective by triangulating the results of the survey data since 2016 with the oral testimonies of workers who witnessed the changes that took place locally in platform work over the same period, thus providing a unique insight into the causality of change. Both studies drew on an extensive survey of the existing literature on platform work, a field in which some of the authors were pioneering figures.

Platform work – lessons from the literature

Since online platforms first appeared on the scene in the early 2010s, a large body of theoretical and empirical literature has emerged, focusing on many aspects of their evolution, business models, digital management and employment practices and roles in economic development. Likewise, there is also considerable scholarship on platform workers, including their motivations, self-characterisations and class consciousness, earnings, experiences of precarity, needs for flexibility and demographic characteristics. For reasons of space, we focus in this section only on those studies that have a direct bearing on our research methodology and conclusions.

Typologies of platform work

Some authors (e.g. Srnicek, 2017; Langley & Leyshon, 2017) define ‘platforms’ very broadly, including, for example, e-commerce platforms and social media platforms, in which intermediation is taking place across many different functions. Here, we are concerned more narrowly with platforms that are intermediate in the provision of paid work between clients and workers. A number of different typologies of platform work have been developed.

These often involve some combination of the location where work is carried out, the contractual status of workers, the nature of the tasks carried out (in particular, whether they involve the processing of digital content or the delivery of services in real time and space and the duration of the relationship) and, in some cases, the business model of the platform (see, for example, Eurofound, 2021; Huws, 2015b). Here, some frequently cited authors include Vallas and Schor (2020), De Groen, Maselli and Fabo (2016), Howcroft and Bergvall-Kåreborn (2018), Graham and Woodcock (2018) Berg et al. (2018), Schmidt (2017) and Vandaele (2018). In most cases, broad distinctions are drawn between, on the one hand, work that is carried out ‘online’ (Vandaele, 2018), sometimes described as ‘web-based’ (Berg et al., 2018; Schmidt, 2017) or as a ‘virtual global service’ (De Groen, Maselli & Fabo, 2016). This may be further broken down into low-skill ‘micro-work’ (Tubaro, Casilli & Coville, 2020) or ‘clickwork’ (Reese, 2016), which is contrasted with higher-skilled work, often with an acknowledgement that it may be difficult to distinguish these categories with precision (Wood, Graham, Lehdonvirta & Hjorth, 2018). On the other hand, we find grouped together a range of ‘offline’, ‘location-based’ work (Berg et al., 2018; Schmidt, 2017; Vandaele, 2018), ‘location specific’ (Graham & Woodcock, 2018); and ‘physical local services’ (De Groen, Maselli & Fabo, 2016) covering various types of platform-enabled services provided in real time and space. Again, these are sometimes broken down into sub-categories including a distinction between algorithmically managed work ‘in public spaces’ and ‘in other people’s homes’ (Huws, 2015a) or between the ‘transport sector’ and the ‘home services sector’ (Surie, 2020). Attempts to distinguish between delivery work and taxi services have increasingly broken down because of increasing convergence between these activities, with many workers combining both kinds of activity (see, for example, Urzi Brancati, Pesole & Fernandez Macias, 2020) and some platforms, such as Uber, combining both within a single platform, while in other contexts, such as Indonesia (Rachmawati et al., 2021) the same ‘goji drivers’ used their vehicles for both purposes. Added to this difficulty of definition is the extreme rapidity with which online platforms change their business models. Drawing on this literature, for the purposes of this study, we focused on the combined category ‘driving and delivery work’.

Platform work and the pandemic

Many of the studies of platform work published during the pandemic were inevitably required to speculate about the long-term impact the pandemic would have on platform work, (for example, Tubaro & Casilli, 2022; Huws, 2021) and were qualitative in nature. A number of studies from the developing world (Parwez & Ranjan, 2021; Rachmawati et al., 2021; Rani & Dhir, 2020) provided compelling evidence that the requirement to work during the pandemic had raised new challenges for platform workers in driving and delivery, rendering the work both more precarious and more dangerous, while often accompanied by a drop in earnings. Some European studies (Schreyer, 2021; Renau Cano, Espelt & Fuster Morrell, 2021; Allegretti, Holz & Rodrigues, 2021) drew attention to several ways in which particular platforms used the special circumstances of the pandemic to change their algorithms, often to the detriment of workers.

At the time of our research, there were no quantitative studies revealing the impact of the pandemic on the extent and characteristics of platform work. The second wave of the COLLEEM survey (Pesole et al., 2018; Urzi Brancati, Pesole & Fernandez Macias, 2020), a valuable source of information on platform work in Europe, was carried out in 2019, before the pandemic struck, with the third wave (the results of which were still unpublished when we wrote this article) scheduled for 2022. When drawing conclusions from our research we were, however, able to draw on the findings of one US study (J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., 2021), which examined households involved in the online platform economy (including looking separately at those involved in ‘transportation’, defined as including ride-hailing and food delivery) in relation to claims for unemployment insurance, which provided some insights into their poverty levels compared with other households.

The platforms studied – Deliveroo and Uber

The qualitative research on which this article draws was carried out with workers using two platforms: Deliveroo and Uber. As the research developed, however, it became increasingly apparent that many workers worked for more than one platform. Furthermore, there was a diversification of business models among the platforms that eroded the boundaries between driving and delivery work. Our results therefore have a broader relevance for platform-organised driving and delivery work, beyond these two specific platforms.

Deliveroo is headquartered in London, where it was founded in 2013. Its business model relies on workers picking up deliveries directly from restaurants and the arrival of platforms providing this service has been estimated as substituting for 56% of deliveries previously ordered directly from restaurants (Deloitte, 2019). Although restaurants prefer to use smaller platforms, like Just Eat or Takeaway, which allow them to employ their own delivery personnel for half the charge, they are forced to join Deliveroo and Uber Eats because these platforms control the largest share of the market, despite charging a large commission (around 30% [Hickey, 2022]). During the second lockdown (November 2020), more restaurants and small food suppliers signed up with the three larger platforms (Deliveroo, Uber Eats and Just Eat), while complaints about the high commissions increased (Hancock & Bradshaw, 2020). The number of Deliveroo riders in London is not known but amounts to at least several thousand riders, and according to key informants also increased during lockdowns. After a general drop in demand for cooked food, but an increase in demand for groceries, in 2020 there was a sharp rise in deliveries across the UK, mainly due to reorders rather than new customers (RTE, 2020). The UK is estimated to be by far the largest ready-made meal delivery market, with a value of €15 billion, compared with €6 billion in Germany and €2 billion in France (Pasquali, 2022). Despite the initial drop in demand, delivery platforms became the biggest winners of the COVID-19 crisis, increasing their numbers of restaurants, orders and riders. These trends also echo those found in the USA by J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. (2021) who note that ‘Further into the pandemic, as restaurants and other businesses adapted to online ordering and delivery, many rideshare drivers switched to delivery’ (J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., 2021).

Uber launched its taxi services in London in 2012 and by 2020 it was estimated that 45,000 drivers used it in the city (Dawkings, 2020). Uber and other platforms absorbed many drivers who previously worked for minicab companies, which almost disappeared from central London. London’s iconic black cabs were less affected by platforms, mainly serving more affluent customers, providing personalised services to businessmen, tourists, groups and other more specialist services. At the time of our interviews, London had four ride-hailing platforms in operation (Uber, Bolt, FreeNow (Kapten) and Ola), with Uber being the largest. During COVID-19, as essential travel was permitted, Uber drivers could continue operating, but as early as March 2020, and especially after the lockdown, demand for services dropped sharply because of business closures, customers’ health concerns, restrictions on movement, international travel bans and the decline in tourism. Nevertheless, Uber managed to rebuild its market. Our research suggests that this was partially because competition decreased. Many black cab drivers could no longer afford to maintain the high costs of vehicles (rent, fuel and maintenance) when demand for their more specialised services was declining. Even at the end of the pandemic, it was not clear how many traditional taxis would be able to return. The situation was exacerbated by road closures in central London, where most black cabs operate, designed to promote cycling and walking at the expense of road traffic (Mayor of London, 2020). With an estimated 3.5 million uses, London is Uber’s largest market, representing one of its ‘fab five’ global cities (Keown & Saigol, 2020).

Methodology

Surveys

The surveys, covering working-age adults across the general population, were carried out in 2016 and 2019 by the University of Hertfordshire in collaboration with FEPS (Foundation for European Progressive Studies). Detailed discussion of this research can be found in Huws, Spencer and Coates (2019) and Spencer and Huws (2021), which include a discussion of the efforts taken, through stratified sample recruitment and weighting, to ensure that the samples (comprising 2,238 in 2016 and 2,235 in 2019) were as representative as possible of the working-age adult population. To assess the impact of using online surveys for this work, additional offline surveys were carried out in two countries. These are reported by Spencer, Syrdal and Coates (2022) which demonstrates that the results obtained from the online surveys are consistent with what would be expected using other survey modes.

The 2021 survey was conducted in collaboration with the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in July 2021, a sufficient time into the pandemic to allow new patterns of working and living to be observed. It targeted 18–75-year-olds in England and Wales who were at work or had lost their employment as a result of the pandemic and was thus well-placed to identify how platform work was evolving. As with the 2016 and 2019 surveys, stratified sampling and weighting were used to ensure that the sample (of 2,203 respondents) was as representative as possible of the target population. A comparison of the data obtained from this survey with the 2016 and 2019 surveys, at the level of England and Wales, together with further details of sampling and weighting, can be found in Spencer and Huws (2021).

The approach taken in designing all three surveys was to acknowledge that, even in the academic literature, the terminology surrounding ‘platform work’ is not well-defined in terms of its contractual status or occupation. As a result, rather than asking respondents if they were a platform worker, in the way one might ask (defining them by the type of contract) if they were a temporary agency worker, or (defining them by occupation) a plumber, it was necessary to ascertain how respondents found work and how they carried out this work. Combining responses from these questions enabled respondents to be identified as platform workers. Filter questions were used to identify respondents who not only looked for work through platforms but went on to find and undertake such work. The type of platform work carried out (driving/delivery, household services, running errands and online work) could be identified, as well as the frequency with which it was done (at least once a week; at least once a month; at least every six months; at least once a year; or less frequently). It was also possible to ascertain the proportion of the respondent’s personal income which came from platform work. The analysis that follows is based on workers who reported carrying out platform work at least weekly.

In-depth interviews

As well as being the largest centre of platform work, as explained below, London also leads the rest of England and Wales in terms of trends in platform work, making it a particularly interesting site to explore the pandemic experiences of platform workers. It was fortunate that, simultaneously with these surveys, the team was also carrying out interviews with platform workers in London as part of the Platform Labour in Urban Settings (PLUS) project. This research included 15 interviews with taxi drivers using the Uber platform and 10 with Deliveroo delivery riders, supplemented by focus group discussions on the impact of the pandemic on platform labour, with the participation of Uber drivers and Deliveroo riders as well as other stakeholders. 3 Some interviews, carried out in late 2019 and early 2020, were face-to-face. After the lockdown, introduced in London in March 2020, online means were used.

In October 2020, two online focus groups included Uber drivers, Deliveroo riders and one driver who worked for both platforms as well as trade unionists, policy stakeholders and academics, with a focus on the impact of the pandemic on platform work. These discussions provided insights into how the platform economy was being transformed as a result of COVID-19 and opened up a longer-term perspective, affording an opportunity to reflect on the changes taking place in the lives of platform workers during and after the lockdowns.

Demographically, our interview respondents were broken down as follows:

Age: Riders using Deliveroo tended to be from younger age groups (19–42), while Uber drivers were older (29–68). This reflects the finding from other studies that Uber drivers tend to be older than other platform workers (House of Lords, 2017; Young & Farber, 2019), perhaps because of the much larger investment required to purchase a car than a bike or moped.

Gender: Only four of the Uber interviewees and one of the Deliveroo interviewees were female, reflecting the picture from our survey data that these two sectors are not only male-dominated but becoming more so.

Citizenship and country of origin: 18 of the 25 interviewees had British citizenship, three of whom were born outside the UK (Ghana, Cameroon and Afghanistan). Seven had European citizenship (French, Greek, Irish, Italian, Romanian) and two had Bangladeshi citizenship.

Employment status: Except for some students and pensioners, most were self-employed and had paid for the costs and maintenance of their own equipment (cars, petrol, bicycles, mopeds), which were either bought or rented. Uber drivers often had loans to repay for their vehicles. Most platform workers were responsible for their own accounting and tax, insurance and social protection. One driver stated that ‘[e]xcept a tiny software provided by Uber, the rest of everything is provided by me: insurance, car, petrol, mobile data, mobile phone: everything’ (Uber Lon M 10). 4

General trends in platform work from 2016 to 2021

This section draws on the results of the surveys in 2016 (which had 1,284 eligible respondents in England and Wales), 2019 (1,270 respondents) and 2021 (2,095 respondents) to provide an overview of trends in platform work in England and Wales. The next section drills down further into the data to explore regional differences and, in particular, the London context.

Figure 1 shows how levels of platform work increased and intensified from 2016 to 2019 and from 2019 to 2021. While in 2016 those undertaking platform work at least once a week accounted for approximately half of those who undertook any platform work, this balance had shifted so that, by 2021, about two-thirds of those undertaking platform work were doing so at least once a week.

Frequency of platform work (of any type) in England and Wales

Note: Margins of error were approximately ±1.5% in 2016, ±1.9% in 2019 and ±1.6% in 2021.

The rest of the analysis focuses only on those who undertake platform work at least weekly. Figure 2 shows the trends in four types of platform work: online work; driving and delivery work; household services; and errands. It is notable that all four types of platform work had increased a year into the pandemic (July 2021) but were following patterns of growth already established between 2016 and 2019. Notably, it was driving and delivery work that showed the sharpest growth.

Type of platform work undertaken by those who undertake platform work at least once a week in England and Wales

Note: Margins of error were approximately ±0.9% in 2016, ±1.3% in 2019 and ±1.2% in 2021.

Looking at the proportion of personal income that these weekly platform workers were obtaining through platform work, a contrary trend is observed. Figure 3 shows that, despite increased numbers of individuals working for platforms at least weekly, the proportion of personal income they are deriving from such work has been falling, with a drop in those obtaining 75% or more, and a corresponding rise in those obtaining less than 25% of their income from platform work both between 2016 and 2019 and between 2019 and 2021. By 2021, over half of the weekly platform workers were obtaining less than a quarter of their personal income from such work, implying not only that most were using it as a top-up to other forms of income but also that they appeared to be putting in more hours of work for lower rewards: a phenomenon investigated further in our qualitative research.

Proportion of personal income obtained from platform work for those undertaking platform work at least once a week in England and Wales

Note: Margins of error were approximately ±9.9% in 2016, ±7.0% in 2019 and ±4.5% in 2021.

Figure 4 shows the gender of those undertaking platform work at least once a week. As can be seen, while there was essentially an equal gender balance in 2016, the proportion of men among those undertaking platform work at least once a week had increased by 2019 and even further by 2021. This growth was particularly pronounced among driving and delivery workers, who were already more likely to be male than platform workers in general. By 2021, nearly three-quarters (73.9%) of weekly platform workers in this category were men.

The London context

This section examines how platform work in London fits within the broader national (England and Wales) and regional (South East and East of England) context.

Figure 1 showed a general national growth in platform work between 2016 and 2021. Figure 5 shows that this was particularly pronounced in London, with an increase between 2019 and 2021 that was not mirrored in the surrounding South East and East of England regions or in England and Wales as a whole.

Frequency of platform work (of any type) in England and Wales by region

Note: Margins of error approximately ±4.6% in 2016, ±5.9% in 2019 and ±5.0% in 2021 for London, ±2.7% in 2016, ±3.8% in 2019 and ±2.9% in 2021 for South East/East of England (excl. London) and ±1.5% in 2016, ±2.0% in 2019 and ±1.6% in 2021 for England and Wales (excl. London).

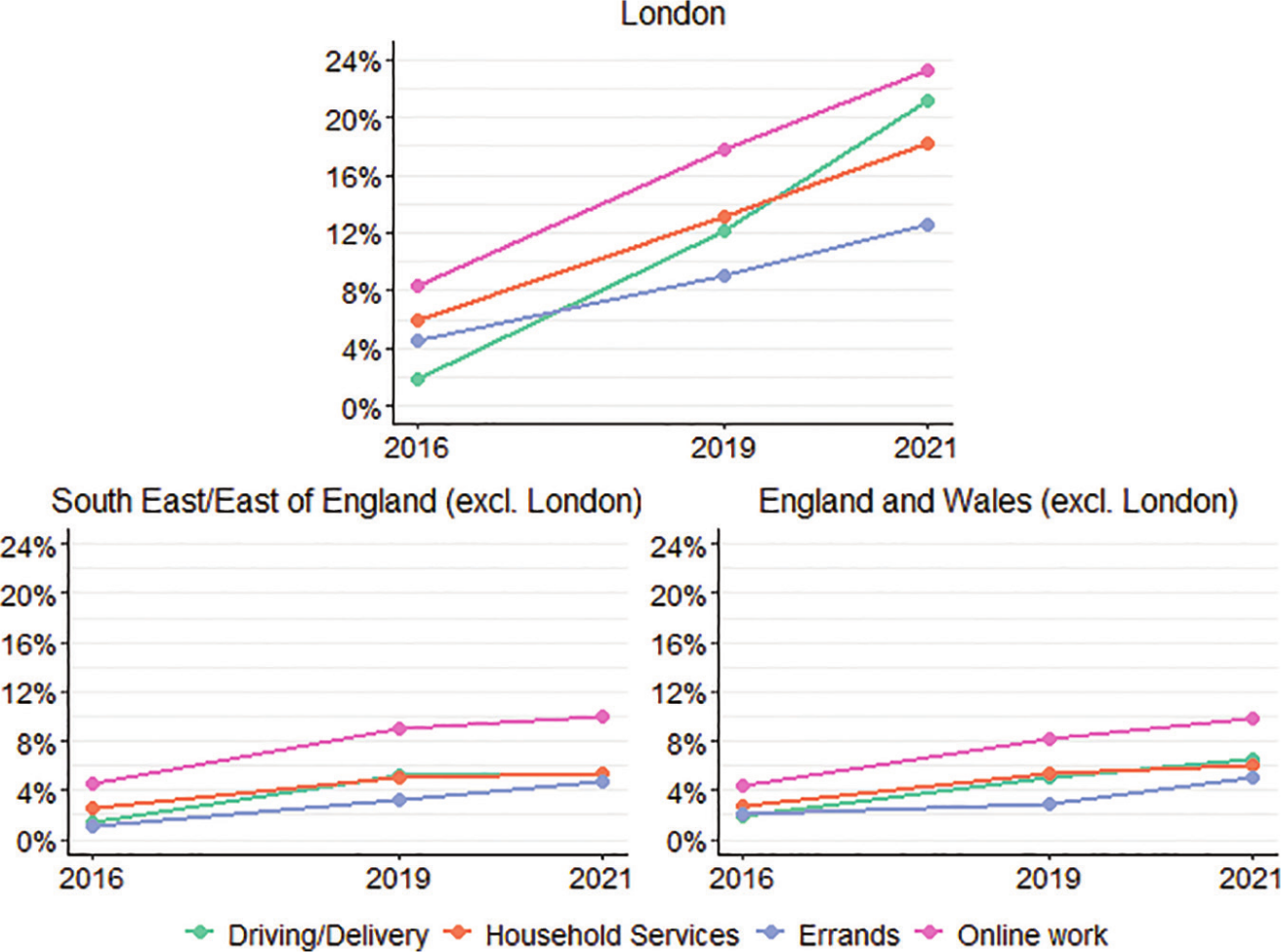

Turning to the type of work carried out by weekly platform workers (Figure 6), it can again be seen that increases in London outstripped those in the rest of England and Wales. Changes between 2019 and 2021 built on earlier trends between 2016 and 2019. In particular, increases in driving and delivery in London during the pandemic represent a continuation of a trend that already existed.

Type of platform work undertaken by those who undertake platform work at least once a week in England and Wales by region

Note: Margins of error approximately ±3.1% in 2016, ±4.6% in 2019 and ±4.0% in 2021 for London, ±1.6% in 2016, ±2.5% in 2019 and ±2.0% in 2021 for South East/East of England (excl. London) and ±0.9% in 2016, ±1.3% in 2019 and ±1.1% in 2021 for England and Wales (excl. London).

In Figure 7 (despite wide margins of error) it is still possible to see a pattern in all regions whereby weekly platform workers are increasingly likely only to be receiving a small proportion of their personal income from platform work. While London is seeing levels of platform work above those in other regions (Figures 5 and 6), this is not due to a larger proportion of individuals working solely as platform workers. Interestingly, these trends paralleled that found by J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. (2021) in the USA who also found that ‘the median driver earns roughly 10% of their family’s total income from transportation platforms’ (J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., 2021) but that ‘platform income as a share of total income has been declining’ (J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., 2021).

Proportion of personal income obtained from platform work for those undertaking platform work at least once a week in England and Wales by region

Note: Margins of error approximately ±20.0% in 2016, ±14.1% in 2019 and ±7.7% in 2021 for London, ±22.0% in 2016, ±12.9% in 2019 and ±10.0% in 2021 for South East/East of England (excl. London) and ±11.4% in 2016, ±8.1% in 2019 and ±5.5% in 2021 for England and Wales (excl. London).

Turning to gender, it can again be seen, in Figure 8, that despite higher levels of such work in London, compared with other regions, the patterns observed in London do not differ widely from those in other regions. The gender balance has shifted since 2016, with the proportion of weekly platform workers who are male increasing as growth in driving and delivery work outpaces that of other types of platform work.

Gender of those undertaking platform work at least once a week in England and Wales by region.

Note: Margins of error approximately ±23.4% in 2016, ±15.9% in 2019 and ±8.4% in 2021 for London, ±23.7% in 2016, ±14.4% in 2019 and ±11.3% in 2021 for South East/East of England (excl. London) and ±12.6% in 2016, ±9.1% in 2019 and ±6.3% in 2021 for England and Wales (excl. London).

London can thus be seen as leading the rest of England and Wales in platform work, making it a particularly interesting site for investigation. The next section examines these trends from the perspective of driving and delivery workers working for two online platforms.

Findings from interviews

Becoming a platform worker

Many of our interviewees were initially attracted to platform work because of the low barriers to entry and the flexibility and independence it seemed to offer. Some delivery workers, for example, said they felt more in control of their lives than in previous employment and it gave them the opportunity to do other things, such as studying. When asked what their employment relationship was with the platform, this food delivery worker replied:

I am self-employed because I believe my sanity will be quite safe if I’m actually self-employed instead of being employed … I’d rather have the flexibility to really work when I want and you know, do something else when I want and so, you know, flexibility was key. (Del Lon M 6, July 2020)

Similarly, many drivers had come to platform work expecting to be able to work without a boss, any time anywhere. They had often spent a period driving for smaller taxi (minicab) firms before joining Uber, which they had been initially attracted to because of its low commission and higher rewards. Work–life balance was also a consideration (Benvegnù & Kambouri, 2021), illustrated by this male Uber driver explaining why he had changed his work schedule:

I make adjustments, because my little one, she started nursery, so again, I have to adjust. I have to adjust because being on daytime, I’m having only allowance of three hours per day of nursery; I have to keep adjusting. That’s if she was going for morning session, 9 o’clock; this year, she was starting 12 … (Uber Lon M 13, May 2020)

Moreover, glossy recruitment campaigns and technological styling had made platforms attractive, as this female Uber driver explained:

They had an advertising campaign for women drivers … And they had a poster up near my house. And it had, like a blonde white woman of mature years who … you know, who looked like me … because otherwise it would never have occurred to me to be an Uber driver. I don’t think I’d even heard of Uber, actually … at that time, you know, I’d certainly never been a passenger. But it was just this poster, because it was nice that somebody actually wanted to employ somebody of my age. (Uber Lon F 4, Dec 2019)

Nevertheless, although motivated by an entrepreneurial spirit that saw ride-hailing platforms as opening up new opportunities, Uber drivers usually ended up expressing disappointment that these expectations had been frustrated, realising that platforms have a lot in common with previous employers, with earlier experiences in precarious sectors being reproduced in a different form.

Although during the pandemic, platforms functioned as a ‘safety net’ offering job opportunities for rising numbers of unemployed, precarious and low-income workers who experienced an unexpected decrease in income because of COVID-19 (Ravenelle et al., 2021), traditional motivations, including the need for any income available, flexibility and work–life balance, continued to operate, albeit sometimes in changing configurations.

The ever-changing algorithms and their impact

One feature of platform work that differentiates it from earlier forms of precarious work is algorithmic control (Wood et al., 2018; Cant, 2019). The Deliveroo and Uber apps are constantly fed with information on workers’ itineraries, habits, choices and decisions, as well as data on clients and providers. Riders and drivers are expected to allow geolocation and productivity monitoring and the collection of these data enable the indirect control of workers, with working hours and payment systems determined by algorithmic learning (Rosenblat & Stark, 2016). Workflow is managed by providing incentives when the supply of labour is low and disincentives when it is high. Working lives are structured by these algorithms. Nevertheless, none of our interviewees could tell us with certainty how the algorithms worked, with their knowledge of algorithms varying according to their socioeconomic background (Cotter & Reisdorf, 2020).

Deliveroo divides London into operating zones: open login areas, where riders can work any time of the day, and closed login areas, where they can register for specific time slots. Before the pandemic, most of central London was an open login area, whereas more peripheral areas were closed login areas. To book slots in the closed login areas, riders needed to have collected a certain number of points. In response, some riders would work in different areas on different days and times to get the highest possible rates, for example working in the mornings in London’s financial district and weekends and evenings in more residential areas. However, this was already changing before the arrival of COVID-19.

Because once … they released the shifts a week in advance, so it would be first come, first served, so there would be like 50 drivers in the EC zone, 52 drivers in the WC zone, so there would only be a certain amount of drivers in each zone, so everyone could get a fair amount of jobs. So, when they stopped that and anyone could just go online at any time, you realised the busy parts of London were just full of drivers and there weren’t enough jobs; there were too many drivers. So, you could understand the frustration that caused for a lot of drivers. (Del Lon M 2)

By spreading the open login areas across London during lockdown, Deliveroo made it easier for new recruits to join the platform and harder for workers who were dependent on the platform to cope with the increased competition.

Similarly, the rate for an Uber ride is not fixed, increasing in certain areas when demand is high and decreasing when it drops. In principle, this gives drivers the opportunity to seek the busiest areas and maximise their income. In the past, these higher fares were used by the platform to bring drivers to areas in which there was a lot of demand, though most drivers said that they were not reliable. As soon as they arrived in the ‘busy areas’, they would find that the rates had dropped back to normal. This was further complicated by the way that Uber’s reward system also relied on other metrics, such as customer ratings and the percentage of rides refused or cancelled by drivers. These metrics also determine the hierarchy of drivers and how many offers each one receives when there is competition. The pandemic and the ensuing drop in demand pushed most drivers to stop searching for the best rates and to accept any rides on offer, no matter how unprofitable, thus, in effect, resulting in lower earnings.

Algorithmic management during COVID-19 impacted the psychological health of workers (Apouey, Roulet, Solal & Stabile, 2021), especially when they felt threatened with arbitrary ‘terminations’ if their ratings fell. For example, delivery riders who reject offers are frequently penalised by being assigned less work, ranked at lower levels or even pushed off the platform altogether. Adding to the stress caused by this uncertainty was a system whereby riders were asked to explain why they had rejected an order, thus feeding the system with information on riders’, customers’ and restaurants’ patterns and preferences, but also – perhaps most importantly – sending an implicit message that refusing orders is an undesirable and unacceptable behaviour that may be penalised.

The earnings–well-being dilemma

Few interviewees could give us precise information about their earnings from platform work because these fluctuated depending on the time of day, week or year and changing weather conditions. However, it was clear that the pandemic brought major changes, including a substantial squeeze on earnings.

Initially Deliveroo riders faced a big drop in demand.

Oh, it’s been a disaster. If I didn’t have savings, I don’t know how I would have been able to manage because it’s completely collapsed. All the work offices are closed … I’m working less hours because some hours are just not viable anymore; but nonetheless, my income is probably like a quarter of what it was before. (Del Lon M 4)

As the lockdown was established, demand rose again, going beyond pre-COVID-19 levels. Nevertheless, riders saw little benefit from this because Deliveroo and other delivery platforms recruited more riders, thus increasing competition and diminishing the margins for profit. As one rider put it:

Flexibility before Covid was great for me because there was more than enough shifts that I could do in the week, where I could make my work-life work around my personal life … But when it obviously reaches a point where we have to work at least six evenings a week to make [ends meet], then it’s kind of a moot concept; it’s not flexible anymore; it’s become precarious. (Del Lon M 4 – Focus Group)

Even before the official lockdown was announced, Uber drivers were badly affected financially because demand for their services dropped dramatically.

So, when they officially made the lockdown, probably about 10 days before that, business started to kind of die down. I used to pick clients up that were telling me this is their last day working in the building; from tomorrow, they’re going to be working from home, so literally, the managers were already … putting the staff to be working from home, so it was already slowing down. Before the lockdown, I could see that business was already drying up, so with the lockdown, it makes it even worse. (Uber Lon M 14)

With a drastic drop in income, Uber drivers faced a stressful dilemma: how to continue to earn a living while also keeping themselves and their families safe. Uber did not provide them with the necessary protective equipment and there was conflicting information on how to protect themselves. When the lockdowns started, several drivers decided to stop working altogether for several months to protect their health. Some had to abandon cars they had been renting for several years and become unemployed.

[We had] drivers returning their vehicles. Some guys had rented by contracts. For example, you can have a three-year contract. At the end of that contract, you pay £200 and the car becomes yours. Guys were forced to return their cars; some even having to return because of finance arrangements: they just couldn’t pay. (Representative of ADCU, SOPO Lab)

This phenomenon was also found in the USA where, according to J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. (2021)

Driver participation fell by more than a third from roughly 1.5 per cent to below 1 per cent in April and May of 2020. Some drop in driver participation is likely due to both a decline in drivers who are willing to drive during a pandemic (supply side) and a decline in the share of people or businesses who would desire driving services (demand side).

Those who were able to cover costs of maintenance and protective equipment continued to work, but at higher risk. Figures for 2020 from the Office of National Statistics (2021) showed that the death rate among taxi drivers was greater than that for bus or truck drivers, who were considered essential workers by the government.

The safety of platform workers during the pandemic emerged as a major source of stress. Platforms developed social responsibility campaigns that addressed the needs of customers, including contactless delivery options (Reuters, 2020), and free or reduced rides for NHS personnel and care home staff (Uber, 2020), while leaving platform workers unprotected. Access to toilet facilities and sanitation were particularly difficult, as explained by a Deliveroo rider:

… some restaurants were a bit reluctant to give access to the toilets, giving us the age-old trick of: ‘Oh, the toilets are broken’. But OK, no problem. But since the Covid, it’s just not happening … Knowing that, if we do go to the toilet, a sanitiser or disinfectant will do the job as far as we are finished and just sanitise and … so I don’t understand that logic, but anyway … so I literally have to break the law. You can imagine south Kensington, trying to find a place where I can … (Del Lon M 6)

To protect customers and drivers from infection, Uber announced that partitions would be placed in all vehicles, but the costs had to be covered by the drivers, further reducing their incomes (Tubaro & Cassili, 2022). It was a widespread view among our interviewees for both platforms that workers’ safety was subordinated to the needs of customers, and platforms only provided workers with protection when the government or local authorities made it obligatory or when there was protest.

One Uber driver summarised her conflicting feelings about working during the pandemic in the following words:

And so I just kept on working throughout the lockdown and actually, I regarded myself as a key worker – and particularly getting NHS staff to work, because of course, at the start of the lockdown, both Uber and Ola gave deals to NHS workers – I mean, I think Uber gave them free; Ola, I think it was half price – and so I met a lot of … NHS doctors and nurses going to work. And that was actually quite a sobering experience, you know, because … a lot of them were working in intensive care, ICU and you know, the nurses going onto the wards and … And one nice thing that Uber did, they actually had a campaign in the paper for people to write a thank you letter to Uber drivers. So, I received … this sort of thank you letter from, you know, one of the nurses that you take into work and so that was … I just felt it was a war and I was fighting in the war, you know. But my income went down by about half, you know, throughout the lockdown. But unfortunately, I couldn’t claim anything from HMRC [the UK tax authority] because just … it was a strange thing; my gross income from Uber was less than my other incomes and so I wasn’t eligible for any financial support. So … I’m one of the people who’ve fallen through the cracks on that. I don’t really think that was very fair because I had four years of tax returns with Uber, I paid all this tax and … [to] just say: ‘Oh sorry, you’re not getting anything’ because of this technicality, that was quite difficult. (Uber Lon F 4 – Focus Group Discussion)

Regarding welfare, Deliveroo introduced an Emergency Hardship Fund, with provision for 14 days of payment in excess of the equivalent statutory pay for 14 days for sick platform workers who were diagnosed with COVID-19. However, the scheme was criticised because it required riders to provide an official diagnosis of COVID-19 or a doctor’s order to self-isolate. These certificates were difficult to obtain, given the unavailability of tests during the first lockdown. Uber also announced a social insurance programme to compensate workers when they were on sick leave, which proved to be ineffective, leaving most drivers who contracted the virus without support and providing others who were sick with only £200 per month compensation – not enough to live on.

The pandemic thus introduced severe financial hardship for some platform workers, but this was not experienced equally. Platform workers in delivery faced different challenges from those in ride-hailing. The former experienced increased demand and the ‘flooding’ of platforms with new recruits, whereas platform workers in ride-hailing encountered a stand-still and complete stagnation of demand for prolonged periods. Further inequalities arose from differences in costs: for example, Deliveroo riders who used bicycles had very low maintenance costs, whereas Uber drivers were obliged to continue paying for car insurance, petrol, maintenance, and even rental of vehicles which could not be used to generate income. Some platform workers were further disadvantaged by being unable to access social benefits or state financial support because they did not fulfil the criteria for receiving them.

Many platform workers were thus placed in almost intolerable situations, caught between declining incomes on the one hand and the need to remain safe on the other. Faced with this insoluble dilemma, the main strategies that were adopted were to work longer and harder and to take up ‘multi-apping’– working for multiple platforms to gain more work.

Working longer and harder

The pandemic arrived at a time when platform work was already becoming more time-consuming than before, making it difficult to achieve the earnings levels that had been possible in the mid-2010s, when platform work first arrived in London. Respondents interviewed before the lockdown were already describing changes in the algorithms that created extra unpaid waiting time. For example, the Deliveroo app had originally been based on a simple system whereby restaurants would click a button when the food was ready and then the app would send a request for a rider to come and pick it up. Subsequently, it was adapted so that riders were automatically assigned to orders without the restaurant having to tell them when the food was ready. This often resulted in unpaid waiting time, sometimes leading to conflicts between riders and restaurants.

[T]hat kind of relationship between the driver and the restaurant was a bit more human because it was the restaurant themselves who had requested us to come. Whereas now, we are sent automatically to the restaurant, based on Deliveroo’s estimate of when the restaurant should have the food ready and obviously, often there are delays with that, so you can end up being sent to a restaurant 20 minutes before the food is ready. (Del Lon M 3)

Pushing the costs of idle time onto workers did not just depress their incomes but also increased their work-related stress levels and pressures to be on the app longer.

When the pandemic began and unemployment rose, many new riders joined the platform to gain an extra income – leading to oversupply, greater competition for work and longer waiting times. Working for a platform seemed to be the only option for this Deliveroo rider who was working during the early stages of the pandemic (2020):

[S]o I came back from travelling and I didn’t have a job anymore and it was the only thing I could really … yes, so I got a bike, so I was doing it on my bike and it was the only thing I could get at the time … So I had a temporary weekend rider contract, so that meant I could only work on the weekends and they were probably going to terminate it when Covid was over and … was I think what they said … when they gave you a contract, they said, ‘We expect that you’ll probably end your contract when we don’t need you anymore’, which I took to mean [inaudible] … but yes, I got the contract when they were hiring people because of Covid … because the demand went up and they also speeded up the [inaudible] because they needed more drivers. (Del Lon F 8)

After the lockdowns, both Deliveroo riders and Uber drivers testified to increased competition and pressure to overwork. Especially since the summer of 2020, Uber drivers reported going wherever there was work to ensure that they could earn as much as possible and remain logged on for longer periods. Deliveroo riders repeatedly described a similar dilemma: either to work longer hours and accept all the tasks that the algorithm assigned to them (including meeting obscure and unrealistic client demands to ensure good ratings) on the one hand or, on the other, to respect health and safety standards and lose a lot of income. As one rider put it:

Because obviously, I could do this job much safer and earn like 30% less, or … you have to cycle quickly; it’s like you have to, you know and that’s just the way it is, to some degree. And when I first started the job, I quite liked that: it was kind of a bit of an adrenaline rush; but I just had this [inaudible] with this lorry and it was nothing to do with me. My feet came off my bike, basically, just out of nowhere and I came off my bike and I was like seconds away from being in front of a lorry and I just thought, ‘Oh my goodness. Maybe I should get another job’. (Del Lon M 4)

The rise of multi-apping

Registering on more than one platform was already common among the Deliveroo riders and Uber drivers interviewed before the pandemic. When UberEATS was launched in 2016, several riders had switched from Deliveroo to the new platform in order to take advantage of the privileges it initially offered, including hourly rates and a £250 referral fee. The lack of competition combined with better payment made it much more profitable for them to work for the new platform as it increased their profits. Gradually, however, UberEATS was also transformed in ways identical to Deliveroo, leading to reductions in workers’ earnings, more riders registered (thus increasing competition), the replacement of hourly payments with variable ones and a drop in referral fees to £50 followed by their abolition. For many workers, switching back to Deliveroo or working on several platforms simultaneously now seemed like the only option.

Similarly, a high proportion of our interviewees who had previously worked only for Uber had started working for other platforms such as Bolt, Kaptain and Ola since 2017–2018, largely because of the decrease in the amount of work coming from Uber and the rising numbers of drivers registering with the platform.

Such practices increased significantly after COVID-19 because of rising competition for work. For most of our interviewees it was normal to navigate several different platforms trying to find the best combinations and ratings to increase their earnings. Either they had two apps open at the same time or, alternatively, they organised complex daily schedules to take advantage of the best ratings that different apps offered at specific times or locations. For example, delivery riders would log onto new apps when they offered guaranteed hourly payments during less busy times and then switch back to Deliveroo during busier times, when rates were better. Asked whether he used more than one app, this Deliveroo rider replied:

Sometimes, yes, because there may be some time where you are waiting for another job to come in, I’ll turn both the apps on and wait for a job to come in. If I can do both en route, I’ll do that, or if not, I’ll switch one off and then finish the job and then switch them back on again. So I try and mix and match. (Del Lon M7, June 2020)

As ride-hailing work declined for Uber drivers and could no longer guarantee sufficient earnings, many switched to delivery work, often for groceries.

The use of multiple apps helped workers reduce unpaid waiting times and unpaid time spent driving between rides. However, it also brought new stresses, requiring the simultaneous coordination of multiple applications while driving or negotiating through traffic, an activity that brings with it increased risks of accidents (Hill et al., 2021).

Conclusions

This article has combined longitudinal quantitative and qualitative data on driving and delivery platform work in London, the city with the largest concentration of such work in Europe, which anticipates national, and probably international, trends in this sector. Our analysis has demonstrated that platform work continued its previous growth trajectory in the city, despite COVID-19. However, the pandemic provided an opportunity for the online platforms to consolidate their market position, recruiting new workers and adapting their algorithms to optimise their use of this new workforce. Large platforms like Deliveroo and Uber grew to such an extent that they came to be widely considered as essential for the well-being of cities like London, but this did not translate into real benefits for platform workers. Platforms responded to the challenge poorly, failing to commit to workers by acknowledging their employment status or providing income support (Fairwork Foundation, 2020; Howson et al., 2020).

The only significant transformations in the working conditions of platform workers during COVID-19 that had a positive impact, from the point of view of the platform workers, came from the actions of workers themselves and their unions. After a long legal battle, in February 2021, the UK Supreme Court granted worker status to Uber drivers represented by the App Drivers and Couriers Union (Supreme Court, 2021). However even this decision was not fully implemented, with Uber agreeing to grant drivers minimum wage and benefits only for hours worked but not for waiting time. Although platform workers were actively organising during this period and, indeed, winning court victories to guarantee certain employment rights, their bargaining power against the platforms was undermined by the platforms’ over-recruitment strategies and algorithmic changes. The resulting oversupply of labour created increased competition for work. In combination with reduced incentives, this led to a drop in incomes for platform workers, and pressures to work longer hours and adopt unsafe working practices. This has resulted in an apparent paradox whereby, although platform work continues to grow, the proportion of income that it supplies to platform workers is shrinking. The increasing market dominance of the platforms is thus achieved at the expense of the well-being of their workers.