Introduction

In contemporary times, significant employee turnover globally has led to a realisation that ensuring job security has become critical. The loss of skilled labour is becoming acknowledged as a significant risk by numerous enterprises. On the other hand, organisations that recognise their employees as assets will plan for their future goals by offering pensions, motivating them to grow in their jobs, and fostering an environment that supports career advancement. According to Beloor et al. (2020) there is a correlation between welfare and job satisfaction. Education level, job security, rewards and benefits, work environment, management style, and overtime availability significantly affect turnover intention (Makhdoom, 2018). It is therefore important that organisations take responsibility for ensuring their employees’ job satisfaction and retention over the long term.

The textile industry of Sri Lanka plays an important role in the country’s overall economy. The establishment of Export Processing Zones (EPZ), also called Free Trade Zones (FTZ), in 1978 played a pivotal role in expanding Sri Lanka’s apparel industry with a focus on exports. According to Athukorala (2018), the apparel industry in Sri Lanka experienced growth during this period, particularly in intimate and high-end casual wear. The employment opportunities within the garment industry sector are significant. According to the Export Development Board (2023), the garment industry employs around 350,000 individuals directly, and accounted for 46% of the national export revenue in 2022.

Furthermore, the garment industry indirectly employs another 600,000 workers, most of whom are women (EDB, 2023). To meet the demands of consumers who prioritise environmentally sustainable products, the apparel sector in Sri Lanka adheres to established environmental regulations to improve its global competitiveness (Athukorala, 2018). According to Athukorala and Ekanayake (2018), Sri Lankan apparel suppliers have upheld ethical standards in their industry following the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA)1 quotas.

The government was obliged to enhance its existing regulations on ethical commerce in reaction to the termination of the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC), in 2005. Thereafter, clothing manufacturers established themselves as socially responsible enterprises committed to promoting ethical labour practices and environmental sustainability (Ruwanpura, 2016, 2022).

Initiatives like ‘Garments without Guilt (GWG)’ have made it easier to promote Sri Lanka as a production hub that prioritises ethical manufacturing, improves the well-being of workers, and reduces poverty (Ruwanpura, 2016:424). The provision of complementary education and healthcare services in Sri Lanka has resulted in a workforce that is both well-educated and in good health, which is further safeguarded by labour legislation., The ‘GWG’ initiative aims to support the effort of the Joint Apparel Association Forum in 2002 in advancing the cause of ethically compliant garment factories (Social – Sri Lanka Apparel, n.d.). The recommendations of Ruwanpura and Wrigley (2011) and Ruwanpura (2011) also supported the ethical production system and ethical corporate codes for the garment industry.

Despite being considered a model of compliance in South Asia (Ruwanpura & Wrigley, 2011), the Sri Lankan garment supply chain is plagued by job insecurity, causing frustration and fear among many workers in the industry. Outsourcing production processes raises many ethical concerns, including workers’ rights and well-being (Athukorala & Ekanayake, 2018). The apprehension of unforeseen events is a common concern among employees, and the deterioration of job security further intensifies these anxieties (Athukorala, Ginting, Hill & Kumar, 2017; Priyanath & Priyanaganie, 2020).

However, the level of job security is frequently overstated. A firm’s future operational performance and the stability of employment positions are crucial considerations. Nevertheless, prioritising job stability may trigger concerns within the organisation. Individuals who exhibit exceptional performance demonstrate a lack of anxiety over the stability of their job. They possess sufficient confidence to effectively apply their knowledge and skills in novel and challenging situations. Several studies (Gaffar Khan, Huq & Islam, 2019; Alauddin et al., 2019; Rahman, Siddiqi & Basak, 2018) suggest that individuals develop sufficient confidence to effectively apply their expertise and skills in novel and demanding situations when they have perceived job security, thus maintaining a positive workplace administrative environment that could contribute to employees’ well-being. Additionally, encouragement from the immediate supervisor and subordinates, maintenance of a comfortable environment at work, and increased respect for employees could lower presenteeism rates and prevent layoffs from the organisation.

The modern strategy of the Sri Lankan government, which was declared in 1977, has seen the private sector as the driving force of development. To accomplish this principal objective, the government motivates the financial backers; however, it tries to ignore job-related issues. None of the public authorities has focused on a detailed government strategy to address issues identified with job security in the clothing business (Rajapakshe, 2018; Afroz, 2017).

In this study, the researchers endeavoured to assess the components affecting job security in the apparel industry in Sri Lanka, paying particular attention to the unexpectedly high job insecurity within the apparel industry and the government’s lack of intervention in proactively addressing this matter through policy formulation. This made it important to identify significant factors contributing to job insecurity and devise new approaches to address the issue. This study aimed to identify the critical factors that impact job security in the Sri Lankan textile industry and propose a comprehensive strategy to address this issue.

Literature review

Government policies

There are significant aspects of job security that rely on government intervention. Government policies are seen as a safeguard to ensure employees’ job security (Boushey, 2021). These policies encourage stable employment to retain and retain employees (Islam, 2020). Before discussing how unemployment affects job security, it is useful to provide a historical overview of the Federal government’s role in mitigating job insecurity (Boushey, 2021). Government policies protect employees and their families from unemployment and safeguard employees against inappropriate dismissals (Burgess, Sullivan & Strachan, 2002; Ali et al., 2020; Ronconi, Kanbur & López-Cariboni, 2019). Huws (2010:17) has explored how national policies and institutions influence how labour is organised and how people are paid, treated, and enabled to find work in various contexts.

The Sri Lankan government has addressed the issue of job security by passing various laws and Acts through parliament, such as the Industrial Disputes Act (IDA) and the Termination of Employment of Workmen Act (TEWA) (Department of Labour, 2021), which help employees secure their employment and make it illegal for employers to lay off workers for various reasons. (Ronconi, Kanbur & López-Cariboni, 2019). Furthermore, the government has enacted numerous laws and regulations to assist firms in laying off employees by providing them with unemployment benefits. This demonstrates that employability can vary depending on the economic condition of the country (Pologeorgis, 2021). The apparel sector’s contribution to the Sri Lankan national economy is substantial; thus, regulations and laws are being enacted to safeguard their employment.

Compensation is provided based on Sri Lankan government legislation and termination of employment acts to compensate employees who have been laid off. However, the same compensation is used both when companies close and when an employee obtains a voluntary retirement scheme (VRS). A VRS is a scheme approved by the Sri Lankan government for the BOI Companies in 2001 for downsizing employment to improve the organisation’s productivity and make its services more efficient. Under the VRS, if companies cannot ensure their employees’ job security, they can encourage employees to retire voluntarily with a compensation package (F. J & G Saram-Lawyers, 2010; Arumugam & Balasundaram, 2010).

According to the Department of Labour (2021), the Sri Lankan government has made it simple for the general public and employees to learn about revisions and updates, and acts and rules of their employment. On 21 March 2003, the government enacted a unique clause governing termination of employment due to employer termination of employment violations. Despite being granted the freedom to raise these issues with authorities, the research discovered that these matters take a long time to resolve and require reference to a labour tribunal. Similar issues, such as ‘where employers have violated employment termination protocols’, can be resolved by compensating the employee unless the employer is unable to establish that the employee committed misconduct. Even though labour tribunals are available to safeguard labour security, employers may also benefit from changing the direction of a labour case as is evident from research in other national contexts (F. J & G de Saram – Lawyers, 2010). In the Australian setting, for example, Dixon et al. (2019) found that flexible working conditions impacted worker satisfaction, and job instability impedes preventative health practices. This highlights the drawbacks of emphasising work-hours employment regulations without considering job security policies. Gilbert, Huws and Yi (2019) 37examine changes affecting workers’ economic security. If particular tax and regulatory changes accompanied a basic income, workers would have more flexibility to combine jobs, obtain a consistent income,

Skill level

Substantial financial losses in present-value wages often accompany the occurrence of job loss. This phenomenon is not adequately accounted for in prevailing employment and labour market policy models.

The quest for job security and protection has long been recognised as one of the most important variables influencing employee loyalty and performance. Job instability generates many other issues, such as low morale, devotion and sometimes tiredness and other physical diseases (Sanyal, Hisam & BaOmar, 2018).

General and behavioural qualities are frequently employed as proxies for abilities when analysing the social and personal benefits of education and training and the set of expertise in society. When studying the effects of skill levels on the economy, utilising credentials as a metric for expertise is a beneficial and neutral way of analysing a person’s range of talent pool. This does, however, have some disadvantages (Milas, 1999).

There is a direct relationship between skill and job security. Nawaratne (2013) investigated the impact of job restructuring on employee job security in Sri Lanka. Employees with lower qualifications were shown to have fewer opportunities to meet demand; thereby increasing job insecurity. Sinche et al. (2017) also contend that transferable abilities will boost job satisfaction. Highly specialised employees are difficult to replace. Thus, they are less concerned with job security than employees with fewer specialised skills (Emmenegger, 2009; Goldthorpe, 2000). Iversen and Soskice (2001) assume that employees with relatively specialised skills will demand more job security regulations to increase the likelihood of investment return.

Collective bargaining

Research in the UK suggests that job security is a top priority not just for employees, but also for the trade unions that represent them (Skripak & Poff, 2020).

While capital–labour disputes arose throughout the colonial and post-colonial periods, they positively impacted Sri Lanka’s growth path in earlier periods. Since Sri Lanka entered the global economy in 1977, organised labour and collective labour rights, in general, have suffered (Gunawardana & Biyanwila, 2008). Unionisation of workers is becoming more difficult due to legal constraints, intimidation of activists and the risk of corporate flight. On the other hand, local unions struggle to meet the different needs of garment sector workers (Ruwanpura, 2014). Sri Lanka joined the global market in 1977, which has also had an adverse effect on freedom of association and collective bargaining in general (Gunawardana & Biyanwila, 2008).

The historically robust labour movement, union politics and legislative frameworks in Sri Lanka have all been highlighted as major elements influencing the development of its garment industry (Ruwanpura & Wrigley, 2011). Despite this, there are some issues that trade union negotiation has yet to address, such as the absence of a living wage which has considerably worsened numerous problems related to excessive overtime and unstable monthly salaries (Ruwanpura, 2013).

There are several reasons why unionised employees may suffer more workplace uncertainty and job instability than their non-union counterparts, despite the likelihood of termination being lower. When unions boost the flow of information to employees, they are more concerned about job security issues than their non-union counterparts. Another factor is that non-union leaders have more work pressures than public employees (Chung, 2019; Ghilarducci, 1985).

Due to harsh restrictions, workers’ rights to association, assembly and speech have been particularly contentious. Unions and collective bargaining have been systematically suppressed on a massive scale by employers, the government and the Board of Investment (Biyanwila, 2011). In place of trade unions, the Board of Investment advocates the establishment of Joint Consultative Councils (JCCs) at the plant level, with an equal number of worker representatives and managers, as a forum for labour–management relations in the garment sector (Biyanwila, 2011).

Unionised workers value economic security and occupational safety, and their safety expectations differ from those of non-unionised workers. They want their union to play a role in protecting their job security. This condition raises the question of what organised labour is doing to protect workers and what efforts are being made to achieve this. The potential impacts of reduced union wages do not necessarily entail any immediate correlation with subsequent workforce reductions within unionised organisations. Negative consequences of unionisation may emerge if unions make businesses more hesitant to expand their workforces because the union pay impact makes new hires more expensive for unionised businesses than for non-unionised businesses, as well as because employers place additional costs on downward employment adjustments by pay increases (Evans & Spriggs, 2022; Pocock, Kiss, Oram & Zimmerman, 2016; Lynham , 2018).

Alternatively, unions might hinder job creation by slowing revenue development if higher union labour expenses diminish capital returns compared to non-union enterprises. According to OpenStax Economics (2016), internal employment losses have no detrimental influence on union jobs. However, studies into this topic have only recently begun to focus on this. According to these data, employers are frequently active in ‘trying to manage’ job cuts. Based on the available statistics, it is evident that businesses frequently engage in efforts to handle workforce reductions effectively. There are 2,074 workers’ unions in Sri Lanka, with 54.5% in government-supported organisations, 27.5% in public companies, and 18% in corporate organisations. Individuals addressed by trade guilds account for 9.5% of the Sri Lankan population (International Labour Organisation, 2021). Some have a long history. According to the Department of Labour (2020), trade unions were first established in 1841 to strengthen job security nationwide. Our research aimed to investigate whether the presence of these trade unions impacts the job security of textile workers in Sri Lanka.

Status of employment contract

Klandermans, Hesselink and Van Vuuren (2010) investigated job uncertainty regarding any reason, situation or scenario that influences the perceived likelihood, magnitude or both of job loss. We presume that likelihood and magnitude differ independently. As a result, the factors that impact the likelihood of losing one’s job differ from those that influence the likelihood of losing one’s career. The consequences of one aspect are not the same as the consequences of the other. Ethnographic perspectives on voice enactment underline the value of employment agency and the social and cultural context of voice employed in the workplace (Gunawardana, 2014).

Disparities in studies on the impact of temporary jobs on workers’ well-being may be attributable to an inability to distinguish between all aspects of job loss. The likelihood and size of the predicted job loss may have different effects. Employees with temporary work contracts frequently face a greater risk of losing their jobs, but this risk is typically modest. On the other hand, permanent employees regard the possibility of losing their jobs as low but the severity as high. ‘Tough on crime’ issues, ambiguous public policy, macroeconomic uncertainty, the exorbitant cost of obtaining foreign funding, and established organisational limitations in electricity generation and transportation have all been described as stifling structured job development (De Cuyper & De Witte, 2005; Klandermans, Hesselink & Van Vuuren, 2010).

Contract labourers are much more likely than permanent employees to be laid off by corporations, depending on their contract arrangements, including notice periods and contract termination. Companies can act based on employment contracts or agreements in which the employee and the employer agree to continue the service in exchange for a regular payment (Cheng & Chan, 2008; De Cuyper & De Witte, 2005). Terminating a permanent and confirmed employee is easier if there is a valid reason or a code of conduct violation.

Working environment conditions

All employees must possess and are entitled to a workplace or working environment that ensures physical and mental safety. If employers cannot ensure a safe working environment, the absence of job security will result in decreased employee performance, impacting the attainment of the ultimate objectives of the organisation. Even when employees can accurately focus on their job tasks and responsibilities and accomplish their best, they will still not feel that their job is secure in a workplace that fosters poor working conditions, discrimination, and harassment. For this reason, our study also investigated the impact of working conditions (Rajapakshe, 2021).

Research suggests that the sector’s lack of liveable wages, productivity pressures and incentive payments encourage risk-taking. Whether undertaken in Sri Lanka or abroad, shop floor ethnographies have highlighted how management, supervisors, and workers accept risks to their health, safety, and well-being (Ruwanpura, 2022).

Despite having highly skilled employees, companies may lay them off due to unfavourable conditions and poor management decisions. Employees may value transparency when there are numerous changes, layoffs and staff reductions because of business closures and lower earnings. It is critical that companies interact with and explain to their employees what they want and how they will care for their careers. Employees must comprehend the requirements and obligations they must fulfil. When there are many changes, laying off and lowering the cadre owing to ceasing operations and earning fewer earnings, transparency can be critical to employees (Byars & Stanberry, 2018). According to Stasiła-Sieradzka et al. (2020), the work safety climate might influence employee behaviour.

Changes in the supervisor’s conduct may lead to changes in the working environment climate and could lessen animosity, feelings of powerlessness, and physical strain and demotivation among employees. The optimistic mindset of employees has a significant impact on their overall job happiness. (Damij, Levnajić, Skrt & Suklan, 2015). The leadership styles of administrators have an impact on employee performance. Factors such as initiative style, working environment, and job satisfaction are essential leadership characteristics that influence employee performance. Additionally, supervisors’ personalities and occupational anxiety have been associated with employees’ susceptibility to harassment in the workplace (Kang et al., 2017; Sulaiman et al., 2021).

Furthermore, a supervisor’s behaviour affects employees’ well-being, job security expectations and job fulfilment. Positive administrative behaviour in the workplace could lead to helping employees grow even more, while poor administrative practices could have the opposite effect. Furthermore, support from immediate supervisors and subordinates, a casual work environment, and increased consideration for employees may reduce presenteeism rates and lead to layoffs or firing from the organisation (Kang et al., 2017; Chandrasekara, 2019).

According to Mathieu, Fabi, Lacoursière and Raymond (2016), person-oriented leadership has a greater impact on turnover intentions via job satisfaction and organisational commitment than task-oriented leadership. Only organisational commitment had a direct influence on the intention to leave the organisation. Employee demotivation, rather than poor performance on assigned tasks, leads to layoffs or questionable job security. According to Rathnaweera and Jayathilaka (2021), flexibility, additional options and a proactive approach to well-being can improve employee happiness with the working environment; in turn, this impacts employees’ sense of job security.

Consequences of job insecurity

Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt (1984) were the first to contextualise job insecurity as an individual’s sense of being unable to maintain job stability when their employment is threatened. These authors also claimed that job insecurity is influenced by an individual’s subjective views of their workplace. This observation demonstrates that the perception and cognition of individuals contribute to the formation of perceived risks arising from objectively existing hazards.

Workplace instability frequently decreases perceptions of cognitive well-being across multiple parameters (Sverke, Hellgren & Näswall, 2002). Work insecurity is regarded as a stressor, and it has a negative impact on a variety of work-related variables. Job insecurity is associated with negative workplace behaviours such as low job satisfaction and employee devotion, as well as poor health and well-being to a lesser extent.

According to De Cuyper and De Witte (2005), emotional commitment theory explains the negative effects of employment insecurity. This concept explains why transitory jobs suffer less from job insecurity. De Cuyper and De Witte (2005) distinguish transactional and relational psychological contracts. The former focuses on financial and transitory rewards and sacrifices, whereas the latter focuses on socio-emotional transactions, with employment security in exchange for allegiance as a crucial component. This leads to the contention that fluctuations in employees’ pleasure or nervousness may affect other aspects of how they work. According to De Cuyper and De Witte (2005), it is changes in the psychological contract, rather than work uncertainty per se, that cause negative emotions. They demonstrate that violating the relational psychological contracts, rather than the transactional ones, has a detrimental impact on work and life happiness. As a result, job insecurity has a detrimental impact on well-being. Hourly employees are happier at work and in life, compared to temporary employees.

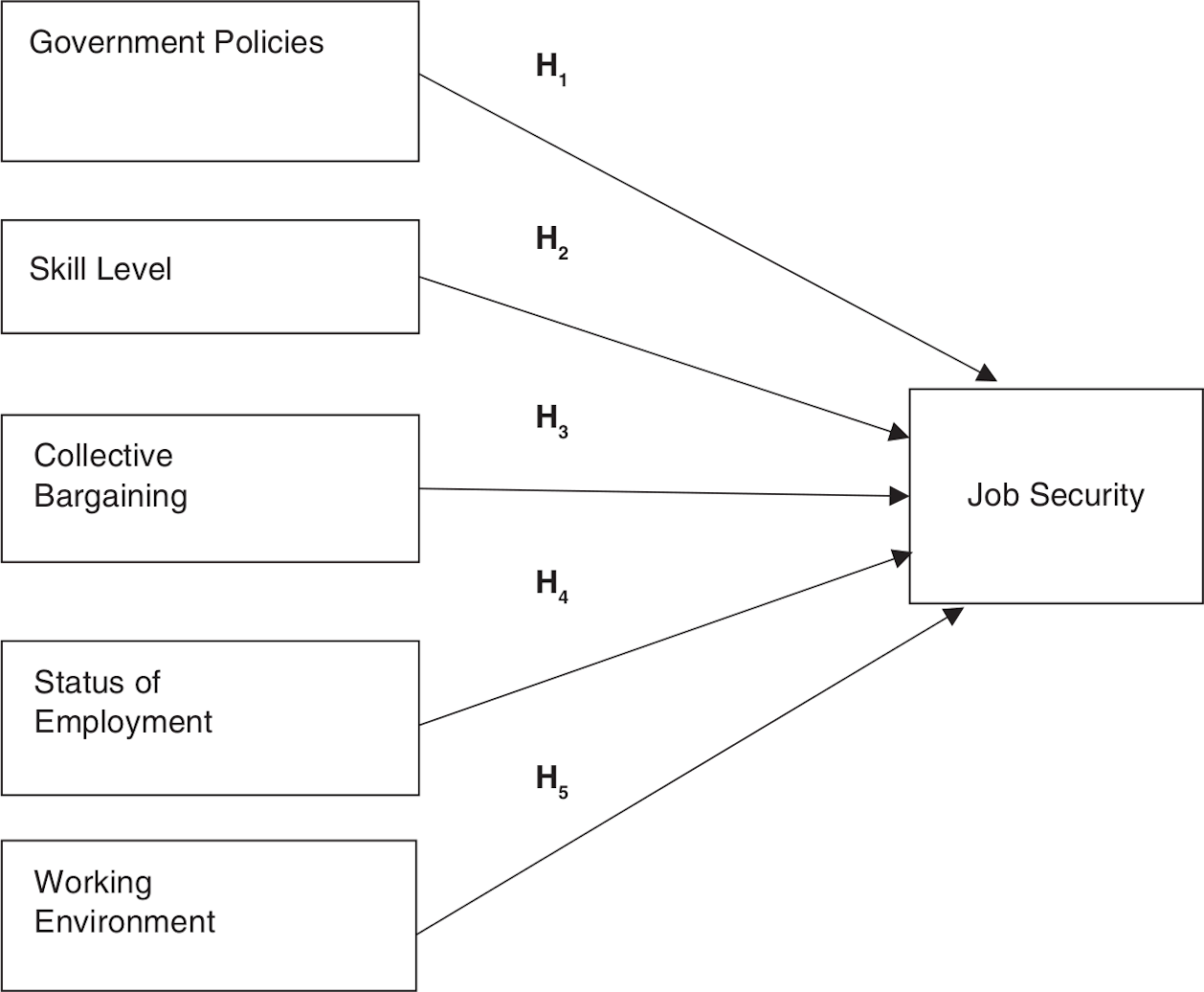

Conceptual framework

Following a literature review, a conceptual framework for testing the hypotheses was devised, as illustrated in Figure 1. Pequegnat, Stover and Boyce (2011) state that the conceptual framework is the foundation for analysis and highlights the potential for building links between variables. It depicts the potential relationships between variables and the stated relationship, which are required for the research analysis to be completed.

The following hypothesis was developed in line with the arguments found in the literature.

Research methodology

The study employed a positivist philosophical framework, utilising a deductive approach to establish the veracity of the underlying assumptions. A research strategy was devised to identify the determinants of job security among white-collar workers in the apparel industry in Sri Lanka. The study employed a cross-sectional survey design, as all observations were collected simultaneously. The study employed a mono approach by exclusively utilising quantitative data collection methodologies and applying quantitative data analysis methods to address the issue. Survey research designs are a quantitative research methodology involving researchers managing a sample or population to depict the population’s perceptions, behaviours, or characteristics (John, 2005).

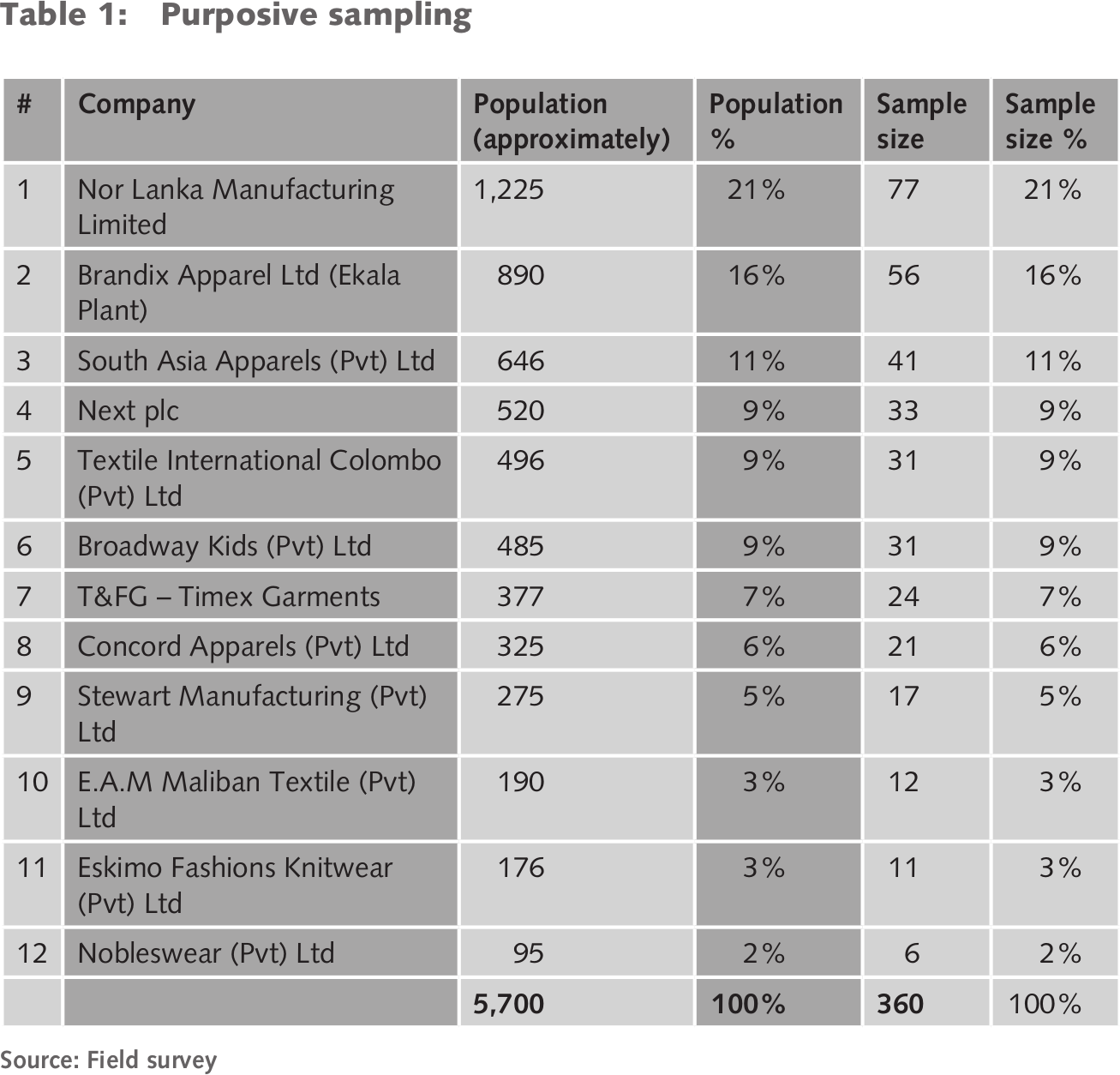

The study’s population was limited to shop- and office-based employees working in the twelve major apparel companies in Sri Lanka, as presented in Table 1. The research project utilised the cluster sampling method in conjunction with the purpose sampling approach to choose a sample of 360 executive and non-executive employees who worked in the offices from a population of approximately 5,700 total employees. First, out of all the employees in the twelve different factories, the office workers were selected as a homogenous cluster, that is, they have similar working conditions. Following that step, purposive sampling methods were utilised to select 360 employees from within this cluster, following the constraints of COVID-19 guidelines. Respondents were chosen using the researchers’ contacts. As a result, the participants were chosen ‘on purpose’ rather than randomly.

The sample size needed for the study was determined using the single population formula, with a 95% confidence level, a 5% margin of error, and a 50% standard deviation, as outlined by Krejcie and Morgan (1970). According to Ritchie, Lewis, Nicholls and Ormston (2013), the purposive sampling technique was utilised to encompass the diversity and significant aspects of the relevance of the population. The purposive sampling technique facilitates the preservation of sample homogeneity, wherein individuals are selected based on their job position and comparable working conditions.

Data collection

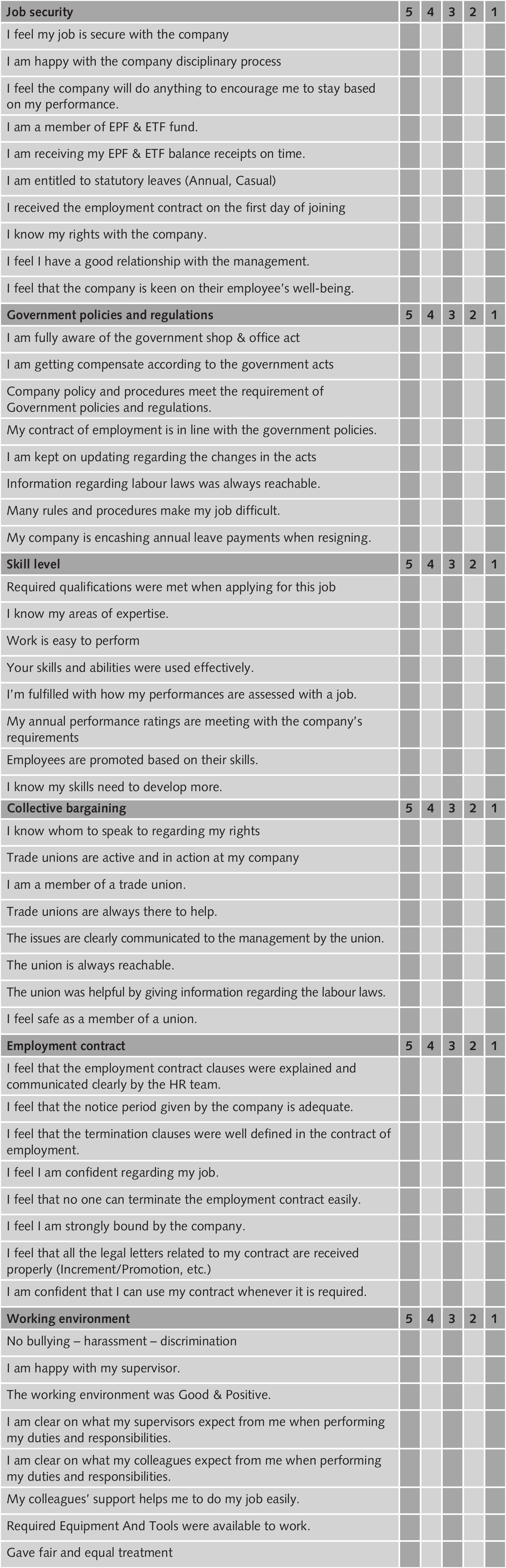

The survey was developed based on a review of the scholarly literature by the investigators (summarised above). The survey questionnaire was partitioned into seven distinct sections (Appendix 1). The first section of the study centred on the demographic characteristics of the employees, while the subsequent sections encompassed data about the dependent variable, namely job security. Athukorala (2018), Ruwanpura and Wrigley (2011), Ruwanpura (2011), and Nawaratne (2013) have all conducted previous research that is consistent with this strategy. The remaining sections of the study contained information on the independent variables, including government policies and regulations (Huws, 2010; Boushey, 2021; Pologeorgis, 2021; Varia, 2010), as well as skill level (Diao & Chen, 2019; Milas, 1999; Nawaratne, 2013; Skripak & Poff, 2020)). The works of Ruwanpura (2014), (Skripak & Poff, 2020), Evans and Spriggs (2022), Pocock, Kiss, Oram and Zimmerman (2016), and Lynham (2018) provide evidence that there are numerous studies about collective bargaining in the literature. The literature suggests that employment status (De Cuyper & De Witte, 2005; Klandermans, Hesselink & Van Vuuren, 2010; Cheng & Chan, 2008) and the working environment (Byars & Stanberry, 2018; Damij, Levnajić, Skrt & Suklan, 2015; Kang et al., 2017; Sulaiman et al., 2021) are essential factors to consider in the study of employment.

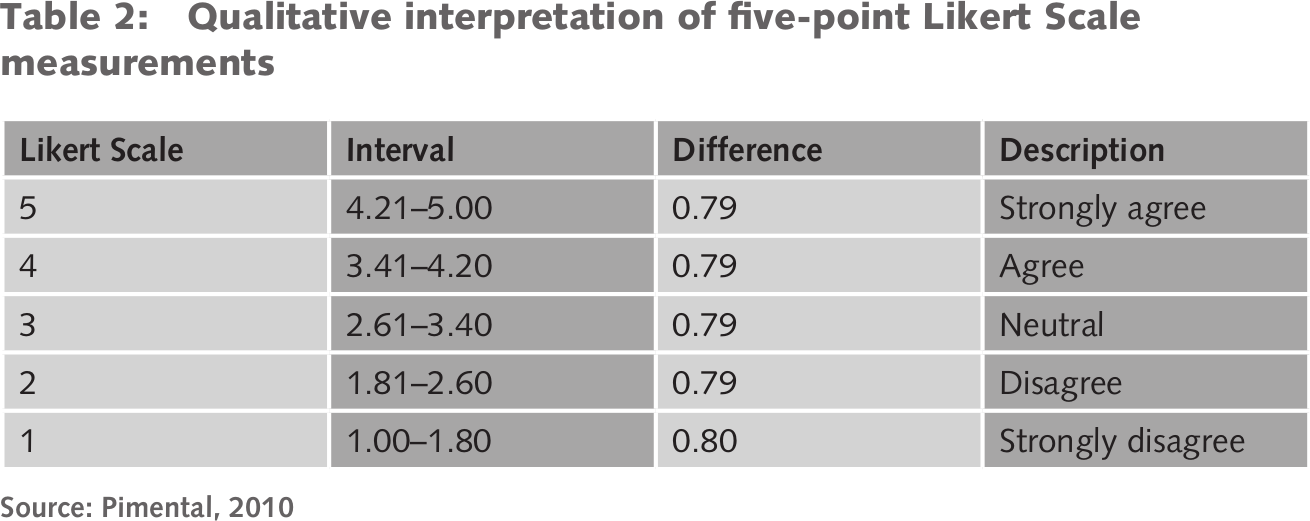

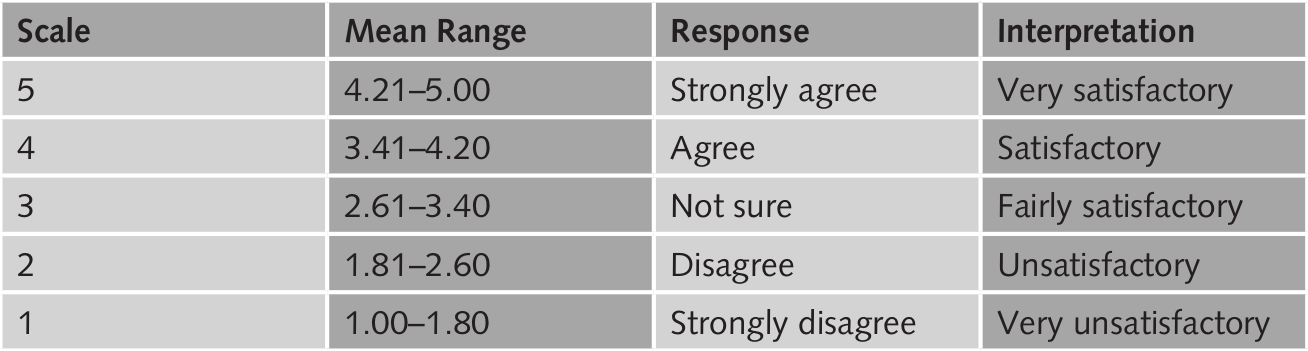

The questionnaire was developed for self-administration and encompassed a range of topics. It underwent a pretest phase wherein a sample of 17 employees, selected randomly and not part of the study population, were administered the questionnaire. The questionnaire included an examination of the respondents’ personal information, as well as the variables relating to their educational attainment, age, and occupational aspirations. The questionnaire employed a Likert Scale consisting of five points, which were categorised as follows: ‘5 = strongly agree’, ‘3 = neutral’, ‘2 = strongly disagree’, and ‘1 = strongly disagree’. This scale is commonly utilised to gauge the attitudes of respondents, as proposed initially by Likert in 1932 (Likert, 1932). The central tendency of the responses for each variable is determined by utilising the averages of the data set. Table 2 (Pimental, 2010) presents the interpretation of the mean value obtained from the five-point Likert Scale.

It is imperative to assess the normality of the dependent variable to enhance the statistical significance of the findings, as suggested by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007). This study utilised a graphical approach to ascertain normality, which entailed an evaluation of the histogram and normal probability (Field, 2009).

To mitigate non-response bias, the questionnaire was physically distributed to 450 employees, resulting in a sample size of 360. The researchers leveraged their personal and professional networks to enhance the response rate. Around 376 individuals (83.5% of the total respondents) answered the survey. However, 16 questionnaires were excluded due to response errors, leaving 360 questionnaires (80%) for data analysis. Thus, the retrieval rate, standing at 80%, is satisfactory and suitable for data analysis, as Fincham reported in 2008.

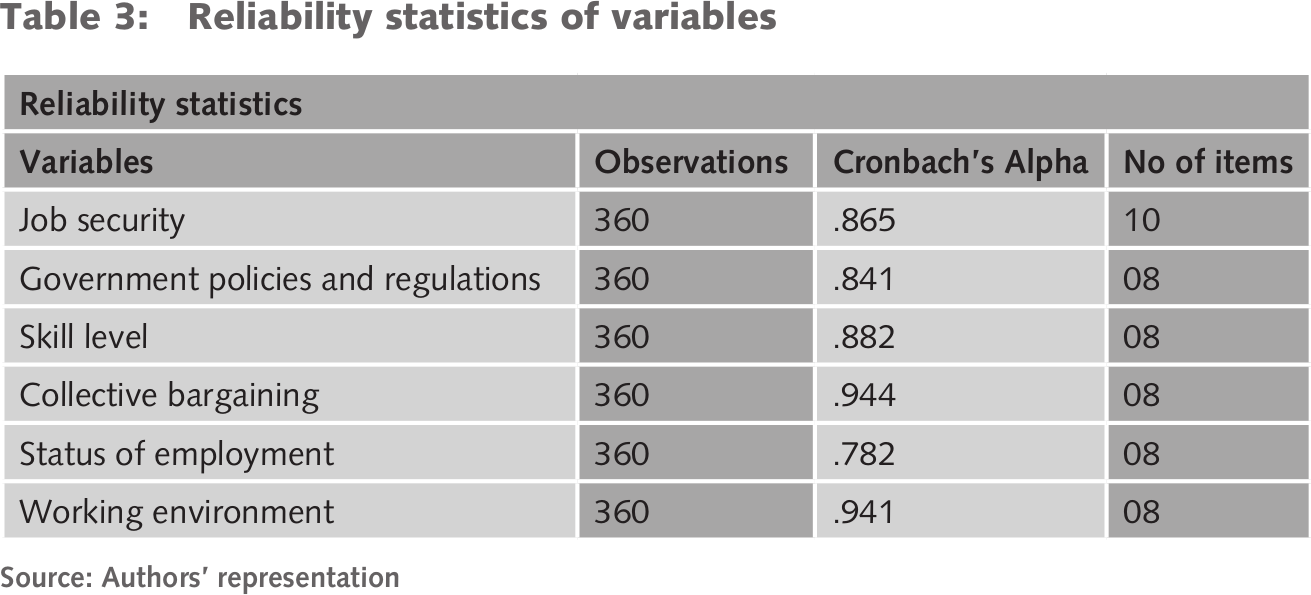

Variable measurement and reliability

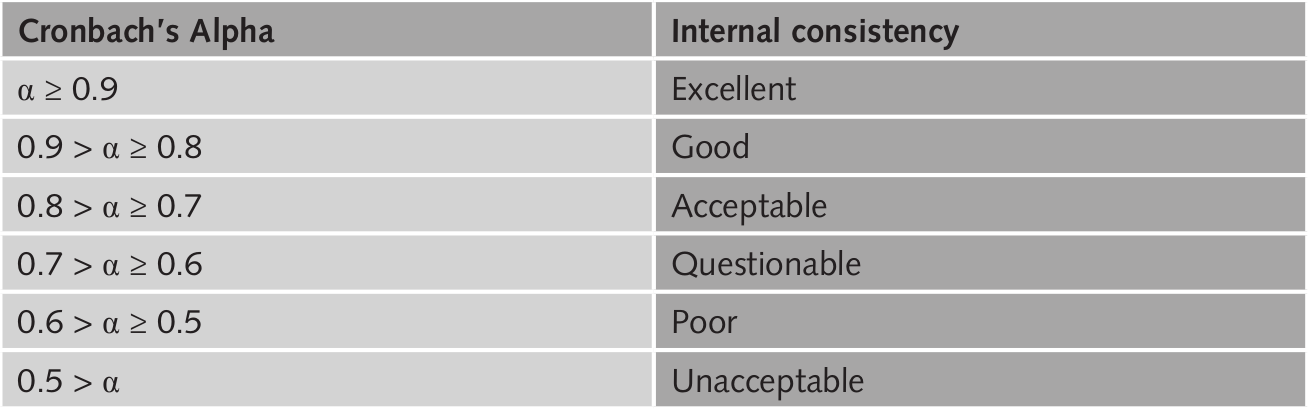

The internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha. Table 3 displays Cronbach’s Alpha values of all variables, which surpass the anticipated threshold of 0.7, as indicated in the accompanying key (Cronbach, 1951). Therefore, it can be inferred that all the variables exhibit high reliability.

Where: N = number of items; C = the average inter-correlation and V = the average variance.

Legend

The assessment of job security was conducted on a ten-item scale, yielding a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.865. The governmental policies and regulations were evaluated through an eight-item measurement scale encompassing job security, compensation, and labour rights. The reliability of this scale was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient, which yielded a value of 0.841. The study incorporated a second independent variable, skill level, encompassing four distinct categories: unskilled worker, semi-skilled, skilled, and professional. The scale used to measure this variable comprised eight items and demonstrated a high level of internal consistency, as evidenced by a Cronbach’s Alpha value of 0.882. Collective bargaining refers to the negotiation process between employers and employees, typically represented by a labour union, to the level of bargaining power evaluated through an eight-item scale with a Cronbach’s Alpha value of 0.944. The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient for the eight-item scale measuring employment status was 0.782. The final independent variable pertained to the working environment, encompassing supervisor conduct, the physical work environment, and the behaviour of subordinates. The study employed an eight-item scale, demonstrating a Cronbach’s Alpha value of 0.941.

Data analysis and presentation

Because it is an essential component in the execution of research (Nayak & Singh, 2021), considerable attention was paid to data analysis. Descriptive statistics were employed to analyse the data to examine the mean value and standard deviation of the levels of agreement and disagreement. The study utilised Pearson correlation coefficient analysis to examine the strength and degree of the association between the dependent variable: the job security of employees, and the identified independent variables.

The study utilised a forward stepwise linear regression technique to assess the predictability of job security through a linear model comprising a predetermined set of independent variables. Variables were incrementally incorporated into the analysis based on their corresponding p-values. The fundamental objective of stepwise regression is to construct an optimal model based on the predictor variables under examination, which explains the maximum amount of variance in the outcome variable (R-squared). The null hypotheses were tested using F ratio values with the appropriate number of degrees of freedom, applying a significance level of 0.05. Multicollinearity among independent variables was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance.

The following linear regression equation was applied to predict the association of independent variables with job security.

Where JS denotes job security, which is the dependent variable, ∝ representing the intercept/constant, β depicts the Beta coefficient or simply the slope for each independent variable and GP = government policies; SL = skill level; CB = collective bargaining; SE = status of environment; WE = working environment denoting the independent variables, and ε = Error Term.

Ethical consent

The research underwent scrutiny by the Research Committee of the SLIIT Business School and was granted approval. Participants were informed of the study’s nature, methods and objectives. The study’s objectives and other relevant information were also communicated to the authorities and volunteers. All participants who completed the survey were incentivised to express their thoughts. Prior to data collection, every participant in the study provided verbal consent. The study participants were not subjected to coercion or monetary incentives to elicit their participation.

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics of respondents

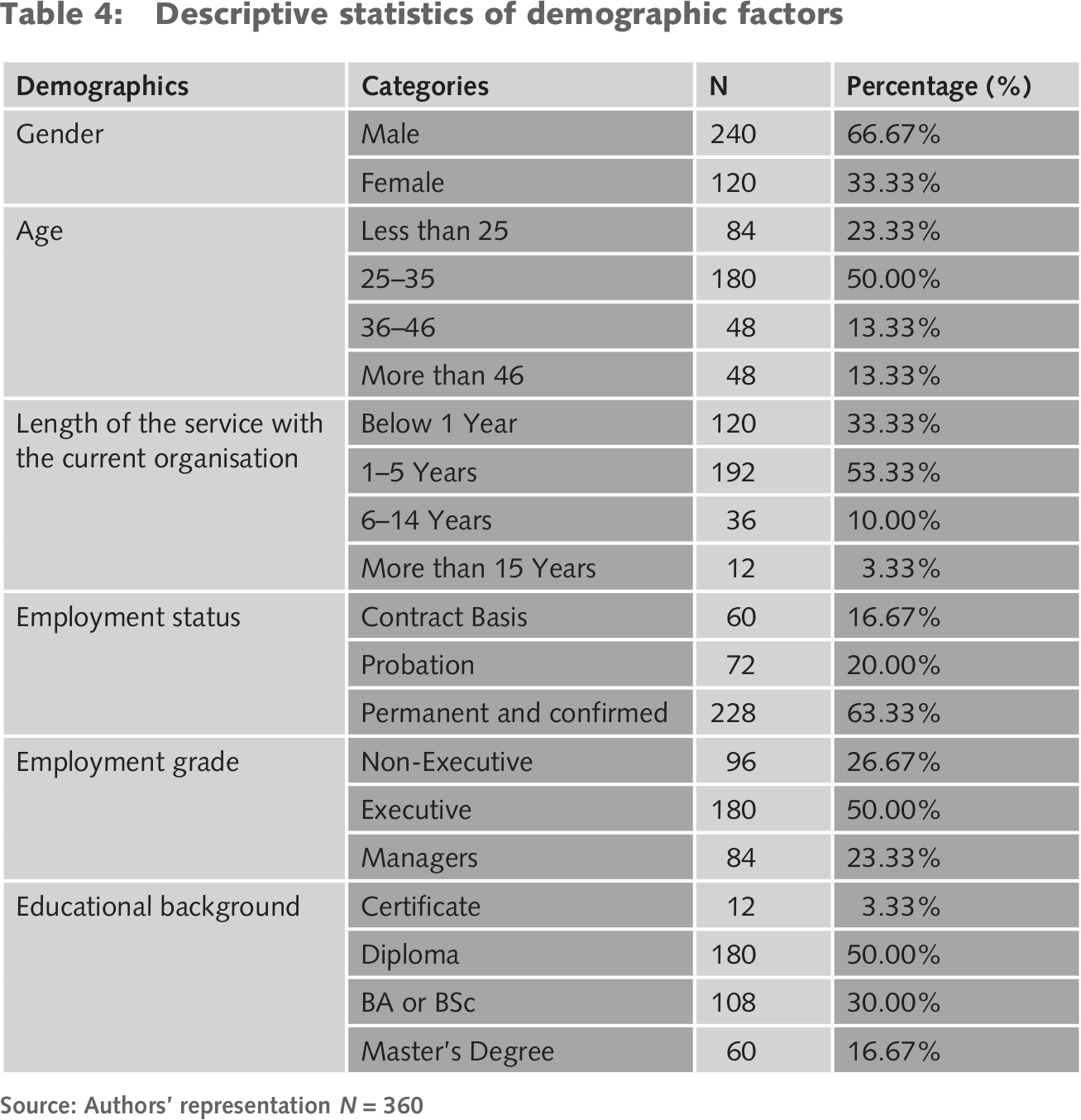

Table 4 presents the demographic distribution of 360 respondents, indicating that 33.3% of the employees were female and 66.7% were male. Additionally, the data reveals that 23% of the employees were below 25, 50% were aged between 25 and 35, and 13% were in the 36–46 age bracket. The largest group of employees (53.3%) had a length of service between one and five years. However, 33% of employees had a service duration of less than one year. The data reveals that most of the workforce (63%) had permanent employment status, whereas a smaller proportion (20%) were on probation. The majority of respondents (73%) were at the administrative level, including 50% of executives and 23% of managers, whereas slightly over a quarter of the employees were non-executives (27%). Half the population possessed a diploma as their educational qualification, while 30% held a graduate degree, and 16.7% had a postgraduate degree.

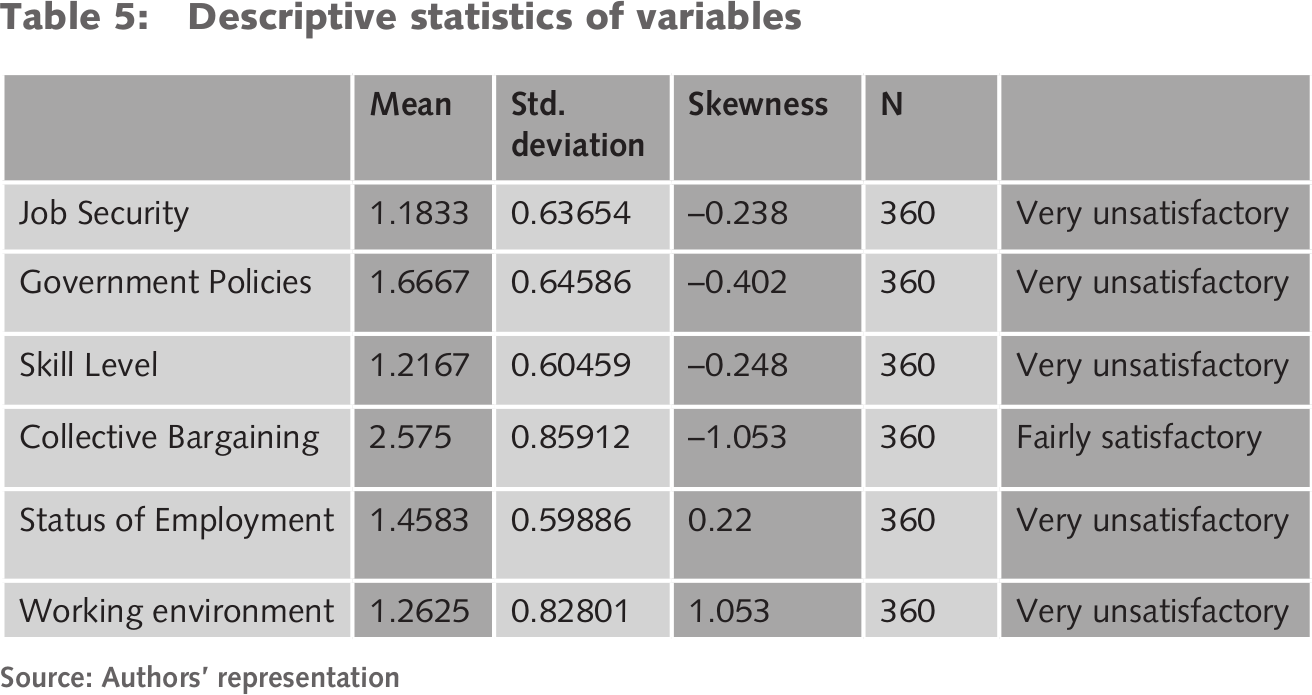

Based on the descriptive statistics, the mean value of the total impact of job security variables was 0.63654, with a deviation of 1.1833. This information indicates that employees are highly dissatisfied with the current state of job security, which is the dependent variable. Furthermore, Table 5 displays the mean values for government policies, skill level, collective bargaining, employment status, and working environment, which were 1.6667, 1.2167, 2.5750, 1.4583, and 1.2625, respectively. These results suggest that employees perceive these factors as needing improvement. Nevertheless, the evaluation of collective bargaining indicated a level of reasonable satisfaction. Thus, the findings indicate that the identified independent variables significantly influence the job security of employees in the institution under scrutiny. The skewness of the dataset, which is indicative of the asymmetry of the probability distribution, is represented by a value of –0.402.

Legend

Normality test

To validate the outcomes of the regression analysis, it was necessary to exhibit a normal distribution in the model residuals. The methodology employed entailed an evaluation of the histogram and normal probability to ascertain the normality of the model residuals. The regression standardised residual histogram revealed that the data was normally distributed by displaying a bell-shaped curve in the histogram of the model residuals. The distribution of variables was observed to be skewed around the mean. Therefore, the assumptions of normality were not found to have been violated.

Linearity and homoscedasticity test

Scatter diagrams were created to test the linear relationship between the dependent (job security) variable and each independent variable. The scatter plots for the relationship between job security and government policy, skill level, and employment contract closely resemble a straight-line pattern. In contrast, the scatter plots for the relationship between job security, working environment, job security and collective bargaining show a random pattern, indicating that the linearity assumption is acceptable. None of the scatter plots exhibit nonlinear patterns, such as exponential or parabolic curves, further validating the linearity assumption. The homoscedasticity assumption was evaluated using the predicted values of the dependent variable. The study’s findings indicate that the variance of residuals remains constant across all support levels, indicating homoscedasticity. Therefore, the linearity and homoscedasticity assumptions were met in this study.

Test of multicollinearity

Apart from the Pearson correlation, the presence of multicollinearity was assessed by utilising the VIF and tolerance to ascertain that the independent variables were not exhibiting high correlation. The findings of Table 6 indicate that the levels of VIF and tolerance were low, with the maximum VIF level being 2.63 and the maximum tolerance level being 0.821. These findings indicate that the presence of multicollinearity did not have a significant impact on the results of the study.

Test of model fit

R-squared and F-statistics were used to assess the modal fit of the linear regression models. An R-squared more than 0.50, between 0.10 and 0.50, or even less than 0.10, is acceptable in social science research only when some or all of the explanatory factors are statistically significant. The R-squared is reliable if the F-test is significant. Thus, the F-test establishes if the response variable-predictor association is statistically trustworthy. Prediction or explanation research can benefit from it (Archdeacon, 1994:168; Ozili, 2023). The R-squared values ranged from 0.458 to 0.661, indicating that all linear regression models were suitable for the investigation. F-statistics values varied from 172.68 to 302.15, and p-values associated with F values were less than 0.05, indicating that the explanatory variables taken together have a statistically significant association with the dependent variable.

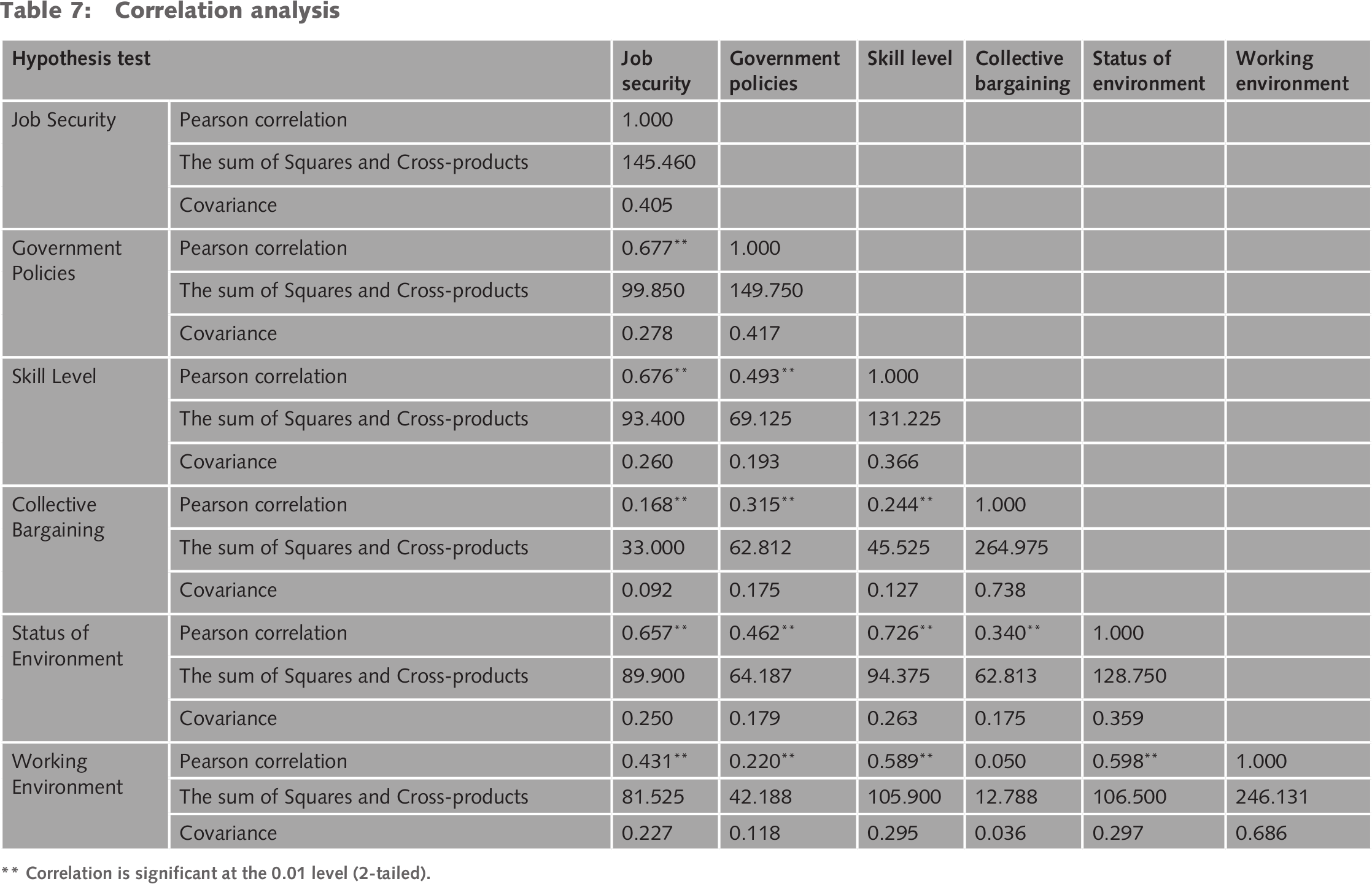

Correlation analysis

The results show that there is a statistically significant moderate positive degree of correlation between job security and government policies, skill level, and employment status, that is, (r = 0.677), (r = 0.676), and (r = 0.657), respectively. There is an association between collective bargaining and job security (r = 0.168), indicating a significant positive but weak relationship. The association between job security and the work environment (r = 0.431) demonstrates a significant moderate positive relationship with job security (shown in Table 7). Furthermore, covariance values range from (0.092) to (0.405), indicating the strong link between the two variables.

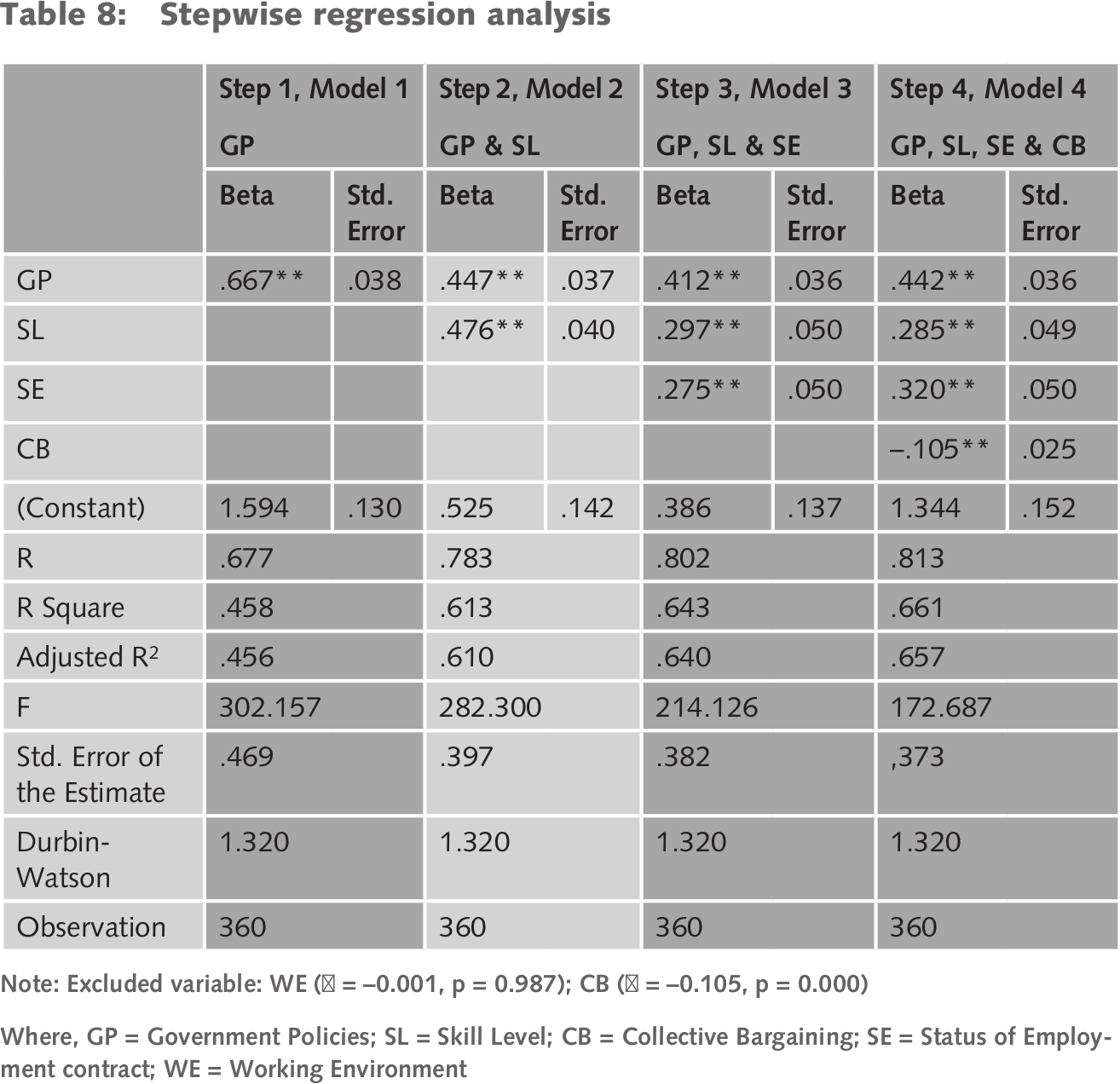

The current analysis concludes that all hypotheses developed for this investigation were accepted. Models 1–4 of Table 8 show the linear regression findings.

The stepwise regressions were significant for job security about changes in government policy, accounting for 45.8% of the variance (R2 = 0.458, P = 0.000). It was discovered (β = 0.667) to have a favourable and significant impact on job security, as shown in Table 8, Model 1, Step 1. Furthermore, F = 302.157 indicated that the regression model was the best match to predict this behaviour. As a result, at step level one of the regression analyses, the determinant elements of job security are government policies and regulations.

Stepwise regression analysis

Note: Excluded variable: WE (β = –0.001, p = 0.987); CB (β = –0.105, p = 0.000)

Where, GP = Government Policies; SL = Skill Level; CB = Collective Bargaining; SE = Status of Employment contract; WE = Working Environment

The Step 2 results of the stepwise regression analysis (Table 8, Model 2) demonstrated that job security with the government policies and skill level of the employees explained about 61.3% (R2 = 0.613) variance. Thus, Job security is associated with government policies and the skill level of the employee is accepted. It implies that employees’ skills, such as unskilled, semi-skilled, skilled, and professional labour, positively affect job security. Moreover, the results showed that the regression model was the best fit to predict this phenomenon as F = 282.300 and p = 0.000 at a 95% confidence level. The β = 0.447 and β = 0.476 for the government policies and skill level of the employee indicated that every unit change in two variables would enhance employees’ attitudes toward job security.

Step 3 research results demonstrate that the regression model had the best match to predict government policies, skill level, and employment status on job security (F = 214.126). As shown in Model 3 in Table 9, the regression result revealed a significant positive correlation between government policies, skill level, employment status, and job security, with p-value = 0.000 at a 5% significant level. Every unit change in government policies, skill level, and employment status increases job security by (= 0.412), (= 0.297) and (= 0.275), with (p = 0.000). The three variables explained 64.3% of the variance in job security (R2 = 0.643, P = 0.000). In Step 3, job security was associated with government policy, skill level, and status of employment.

The predictor variables of government policies, skill level, status employment, and collective bargaining were entered into the regression equation in the fourth step. Their contributions to explaining the criterion variable of job security were calculated as β = 0.442, β = 0.285, β = 0.320, and β = –0.105, respectively, as shown in Table 8 Model 4, Step 4. Every unit change in government policies, skill level of the employees, and status of employment increases job security by 0.442, 0.285 and 0.320, respectively. However, collective bargaining power has a negative impact on job security as the Beta coefficient from regression analysis is –0.105; thus, collective bargaining is not a determinant factor of job security.

The results shown in Step 4 (Table 8) show that the coefficient or R-value of four variables (government policies, skill level, status of employment and collective bargaining) and the dependent variable (job security) towards the apparel industry was 0.813. In addition, the result of R Square (Adjusted R Square is 0.657) shows that 66.1% of variance indicates that the model explains all the variability of the response data around its mean. The last step’s result suggested a highly significant positive regression dependency for the dependent variable by independent variables. The Standard Error of the Estimate is only 0.373, which is the smaller value closer to the dots to the regression line and a better estimate based on the equation of the line. As shown by the F value of 172.687 (P < 0.05), those values substantiate the main hypothesis. At a 5% confidence level, the statistical analysis in stepwise multiple regression demonstrates that three primary dominant elements, government policy, skill level, and status of employment contract, strongly affect job security; however, the collective bargaining, and working environment have little impact on job security.

The derived regression equation is as follows.

Discussion

Overall, the findings of this study are consistent with those of previous studies. The results of the association between government policy and job security are compared with two similar studies in the USA (Boushey, 2021) and Sri Lanka (F. J & G Saram-Lawyers, 2010). The study in the USA examines how the federal government ensures job security to maintain full employment, like in the Sri Lankan context. The government of Sri Lanka also ensures employees’ job security by passing policies. The findings of this study are congruent with those of Boushey (2021), which indicated that government policies are recognised as a protective shield to ensure employees’ job security. Hence, strong government involvement, which facilitates the employees’ job security within a firm, is required. The findings of this study are also supported by research findings in the Sri Lankan context (Department of Labour, 2021; F. J & G Saram-Lawyers, 2010), which revealed that government involvement in the garment industry would increase employees’ job security and retention. According to the Department of Labour (2021), government participation improves employees’ attitudes about job security. F. J & G Saram-Lawyers (2010) claimed that government engagement in terminating employment promotes employees to express their concerns about job security in the labour tribunal. Companies should prioritise receiving government support in making policies, procedures, rules and regulations to reduce employees’ attitudes toward job insecurity. These changes must be properly disseminated to employees, or adverse consequences will materialise (F. J & G Saram-Lawyers, 2010). In addition, Flecker (2010) found that employee fragmentation in the workplace needs to pay attention to national labour market regulations. Huws (2010) showed that national policies directly impact job security. These studies have shown that if the management ineffectively communicates policies, it is likely to generate employee dissatisfaction with job security, misunderstanding among workers, and, finally, impair employee performance. It can be highlighted that government involvement positively impacts employees’ attitudes toward job security.

This study’s findings showed that the employees’ skill level significantly impacts job security, which is consistent with similar studies. Nawaratne (2013) conducted a study based on the Sri Lankan context and found that work restructuring influences job security since employees with lower qualifications may be unable to meet job demands, increasing employment insecurity. The current study is aligned with these findings. Sanyal, Hisam and BaOmar (2018) and Diao and Chen (2019) conducted their studies in China, revealing that job security is influenced by employee performance and competence. Skills have a more favourable association with job stability in Spanish workers (Urtasun & Núñez, 2012). Unskilled Chinese garment industry workers value job stability more than working conditions (Chen, Perry, Yang & Yang, 2017).

Furthermore, Milas (1999) also indicated that skill levels of employees utilise the organisation to enhance their talent. Lower-qualified workers have fewer options to meet demand, worsening employment insecurity. Sinche et al. (2017) claimed that employees’ transferable skills increase job satisfaction. The most competent employees will improve their views regarding job security. Specialised workers are difficult to replace. Thus, they care less about job security than less skilled workers (Emmenegger, 2009; Goldthorpe, 2000). Iversen and Soskice (2001) assume that especially skilled workers want more rigid job security restrictions to maximise investment returns.

Although a significant relationship exists between job security and collective bargaining, apparel employees in our study place little or no value on collective bargaining. Consequently, trade union collective bargaining has a significant but negative effect on job security in the apparel industry. These findings contradict the global concern the International Labour Organisation (ILO) expressed in 2021 that trade union activities enhanced employee job security by preserving their basic employment requirements. According to (Skripak & Poff, 2020) and Ghilarducci (1985), collective bargaining has the greatest impact on employee job security based on the US context. Oka (2016) discovered that trade unions in Cambodia’s garment industry exist to address salary-related concerns, hence indirectly supporting employee well-being.

In the global context, many studies have concluded that organisations must modernise the facilities to minimise labour safeguards against them, defend labour rights, and ensure the jobs of employees (Skripak & Poff, 2020; Evans & Spriggs, 2022; Pocock, Kiss, Oram & Zimmerman, 2016). According to the Department of Labour statistics in Sri Lanka (2020), 1841 trade unions were registered to promote job security in the public and commercial sectors in Sri Lanka. The Board of Investment promotes the formation of Joint Consultative Councils at the factory level, with an equal number of worker representatives and managers, as a forum for labour–management relations in the apparel industry (Biyawila, 2011). However, many private-sector firms have provided terrible working conditions and low pay, resulting in employee dissatisfaction. In Sri Lanka’s apparel industry, workers’ rights to association have been severely restricted. Most of the labour unions are more concerned with compensation than with job security which may explain some respondents’ negative attitudes to labour union activities.

The current study revealed that the status of employment significantly impacts job security. This finding aligned with Dixon et al. (2019), who confirmed that higher occupational-status groups perform better than low-status groups in Australia. According to Klandermans, Hesselink and Van Vuuren (2010), employee employment status significantly impacts job security in the Netherlands. If employees do not adapt accordingly, the result is a decrease in their performance. The article demonstrates that the perceived probability and severity of job losses have varying consequences based on the employee’s employment status.

The findings of Cheng and Chan (2008) are aligned with the current study. Employees in China with longer tenure were more severely affected than those with shorter tenure, and older employees were more badly affected than younger ones. Similar to the current study’s findings, Bakr et al. (2019) found that in Saudi Arabia employment status is a significant factor in job security among faculty and teaching staff in a medical college. De Cuyper and De Witte (2005) investigated the consequences of job insecurity on temporary employees’ types of contracts and their outcomes. They discovered that contract labour is at a higher risk of experiencing layoffs due to contractual agreements.

The current study found no association between environmental conditions and job security among apparel workers in Sri Lanka. However, several studies show that environmental conditions, such as supervisor behaviour, working conditions and administrative changes, can have an impact on job security (Kang et al., 2017; Mathieu, Fabi, Lacoursière & Raymond, 2016; Miner, Glomb & Hulin, 2005; Rathnaweera & Jayathilaka, 2021; Badrolhisam, Achim & Zulkipli, 2019). Furthermore, Bakr et al. (2019) conducted a study using data from educational institutes and concluded that leadership style impacts job security. According to Alonderiene and Majauskaite (2016) and Sulaiman et al. (2021), leadership promotes job satisfaction, reduces turnover and boosts job security. However, the findings of Chen, Perry, Yang and Yang (2017) are aligned with the findings of the current study. Employees in the Chinese garment industry with little or no education give a higher value to their pay, job duration and intensity, social insurance, and skill training than a pleasant workplace. Moreover, in a Sri Lankan context, Gunapalan and Ekanayake (2019) found similar results to the current study: organisational commitment, compensation and perks, working environment, and working conditions are not significant determinants of job satisfaction in Sri Lanka’s garment sector. The results of these studies directly confirmed the results of the current study.

Overall, apparel sector employees’ job security depends heavily on how government intervention protects their employment, the skill level of the employees and the status of their employment contract. First, government intervention is more critical because trade unions have less power to protect job security among apparel workers (Biyawila, 2011; F. J & G Saram-Lawyers, 2010).

Second, job security depends on the competency of the employees and the contract they enter into (Nawaratne, 2013; Dixon et al., 2019).

Conclusion

The results of this study support the hypothesis that government policies, employee skills and status of employment affect job security in the Sri Lankan apparel industry. The apparel industry is the primary export-oriented industry in Sri Lanka, supporting the national GDP. Based on the findings, job security is highly dependent on government policies and regulations, with a positive correlation between the two variables (β = 0.442). Moreover, employee skill level and job security are directly interrelated (β = 0.285). Accordingly, less skilled employees have ensured job opportunities in the apparel industry. When compared to temporary job contracts, permanent labourers receive more benefits. The status of employment and job security have a highly significant positive association (β = 0.320), suggesting that job security will grow as the strength of the employment contracts increases.

The analysis revealed a significant negative relationship between collective bargaining (= –0.105) and job security among Sri Lankan apparel industry office workers. The results of this study indicate that respondents viewed union activities as having a negative and diminishing effect on job security. Moreover, the findings of the current study have demonstrated that environmental conditions do not impact job security in the garment industry.

In summary, government laws and regulations, employee skill levels, and employment contract status all positively and significantly impact job security for office workers in the Sri Lanka garment industry. However, the lower level of collective bargaining of trade union activity negatively influences job security. This finding implies that increased government action, managerial intervention, and employee competence would minimise job instability for employees.

Policy implications

Policymakers should establish appropriate mechanisms to maintain the status of employee contact and improve employee competence to secure job security, which will help reduce job mobility and improve social dialogues for job stability. Several steps, such as fixing minimum wages, retirement benefits, labour union rights, labour standards, vocational education and so on, may be highlighted to safeguard the job security of garment employees. Employee skill development initiatives should focus on underutilised skills to increase organisational performance. To unify workers and alleviate concerns about job insecurity, governments should avoid incorporating political considerations that affect the organisational employment structure. Specifically, governments and policymakers should promote unionism, and governments should not underestimate the combined power of workers. Thus, government intervention is necessary to establish proper trade unions and give them a voice, improving garment employees’ job security.

Limitations

Nevertheless, it is important to note that there are several gaps in this report, which present potential avenues for future research. The primary limitation of this research is its reliance on respondents’ opinions to determine its findings. Recruiting respondents for research in the apparel industry is challenging due to the inconsistent number of participants. The study exclusively involved office workers employed in twelve garment factories. Further investigation is necessary to validate the findings of this preliminary research, mainly through additional inquiries conducted among a diverse workforce across multiple factories. Furthermore, it is imperative to consider the potential ramifications of the proposed policy solution on the labour force in various industries, as this may result in substantial fluctuations in employment within the garment sector. To gain a comprehensive understanding of job security management among workers in various cities, it is necessary to supplement the current poll, which is limited to Colombo, with cross-sector surveys conducted in other urban areas. In statistical analysis, future researchers should consider utilising alternative regression methodologies as substitutes for stepwise regression and qualitative methods such as in-depth interviews. The limitations of this paper provide opportunities for further investigation.