- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Disparities in Incidence of COVID-19 Among Underrepresented Racial/Ethnic Groups in Counties Identified as Hotspots During June 5–18, 2020 — 22 States, February–June 2020

research-article

Jazmyn T. Moore , MSc, MPH

1 ,

Jessica N. Ricaldi , MD, PhD

1

,

,

Charles E. Rose , PhD

1 ,

Jennifer Fuld , PhD

1 ,

Monica Parise , MD

1 ,

Gloria J. Kang , PhD

1 ,

Anne K. Driscoll , PhD

1 ,

Tina Norris , PhD

1 ,

Nana Wilson , PhD

1 ,

Gabriel Rainisch , MPH

1 ,

Eduardo Valverde , DrPH

1 ,

Vladislav Beresovsky , PhD

1 ,

Christine Agnew Brune , PhD

1 ,

Nadia L. Oussayef , JD

1 ,

Dale A. Rose , PhD

1 ,

Laura E. Adams , DVM

1 ,

Sindoos Awel

1 ,

Julie Villanueva , PhD

1 ,

Dana Meaney-Delman , MD

1 ,

Margaret A. Honein , PhD

1 ,

COVID-19 State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Response Team

COVID-19 State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Response Team

COVID-19 State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Response Team

Gregory Bautista ,

Janet Cowins ,

Charles Edge ,

Gail Grant ,

Robbie Gray ,

Sean Griffing ,

Nikki Hayes ,

Laura Hughes ,

Rene Lavinghouze ,

Sarah Leonard ,

Robert Montierth ,

Krishna Palipudi ,

Victoria Rayle ,

Andrew Ruiz ,

Malaika Washington ,

Sherri Davidson ,

Jennifer Dillaha ,

Rachel Herlihy ,

Carina Blackmore ,

Thomas Troelstrup ,

Laura Edison ,

Ebony Thomas ,

Caitlin Pedati ,

Farah Ahmed ,

Catherine Brown ,

Sarah Lyon Callo ,

Kathryn Como-Sabetti ,

Paul Byers ,

Victor Sutton ,

Zackary Moore ,

Sietske de Fijter ,

Alexia Zhang ,

Linda Bell ,

John Dunn ,

Stephen Pont ,

Keegan McCaffrey ,

Emily Stephens ,

Ryan Westergaard

21 August 2020

Read this article at

There is no author summary for this article yet. Authors can add summaries to their articles on ScienceOpen to make them more accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Abstract

During January 1, 2020–August 10, 2020, an estimated 5 million cases of coronavirus

disease 2019 (COVID-19) were reported in the United States.* Published state and national

data indicate that persons of color might be more likely to become infected with SARS-CoV-2,

the virus that causes COVID-19, experience more severe COVID-19–associated illness,

including that requiring hospitalization, and have higher risk for death from COVID-19

(

1

–

5

). CDC examined county-level disparities in COVID-19 cases among underrepresented

racial/ethnic groups in counties identified as hotspots, which are defined using algorithmic

thresholds related to the number of new cases and the changes in incidence.

†

Disparities were defined as difference of ≥5% between the proportion of cases and

the proportion of the population or a ratio ≥1.5 for the proportion of cases to the

proportion of the population for underrepresented racial/ethnic groups in each county.

During June 5–18, 205 counties in 33 states were identified as hotspots; among these

counties, race was reported for ≥50% of cumulative cases in 79 (38.5%) counties in

22 states; 96.2% of these counties had disparities in COVID-19 cases in one or more

underrepresented racial/ethnic groups. Hispanic/Latino (Hispanic) persons were the

largest group by population size (3.5 million persons) living in hotspot counties

where a disproportionate number of cases among that group was identified, followed

by black/African American (black) persons (2 million), American Indian/Alaska Native

(AI/AN) persons (61,000), Asian persons (36,000), and Native Hawaiian/other Pacific

Islander (NHPI) persons (31,000). Examining county-level data disaggregated by race/ethnicity

can help identify health disparities in COVID-19 cases and inform strategies for preventing

and slowing SARS-CoV-2 transmission. More complete race/ethnicity data are needed

to fully inform public health decision-making. Addressing the pandemic’s disproportionate

incidence of COVID-19 in communities of color can reduce the community-wide impact

of COVID-19 and improve health outcomes.

This analysis used cumulative county-level data during February–June 2020, reported

to CDC by jurisdictions or extracted from state and county websites and disaggregated

by race/ethnicity. Case counts, which included both probable and laboratory-confirmed

cases, were cross-referenced with counts from the HHS Protect database (https://protect-public.hhs.gov/).

Counties missing race data for more than half of reported cases (126) were excluded

from the analysis.

§

The proportion of the population for each county by race/ethnicity was calculated

using data obtained from CDC WONDER (

6

). For each underrepresented racial/ethnic group, disparities were defined as a difference

of ≥5% between the proportion of cases and the proportion of the population consisting

of that group or a ratio of ≥1.5 for the proportion of cases to the proportion of

the population in that racial/ethnic group. The county-level differences and ratios

between proportion of cases and the proportion of population were used as a base for

a simulation accounting for missing data using different assumptions of racial/ethnic

distribution of cases with unknown race/ethnicity. An intercept-only logistic regression

model was estimated for each race/ethnicity category and county to obtain the intercept

regression coefficient and standard error. The simulation used the logistic regression-estimated

coefficient and standard error to produce an estimated mean and confidence interval

(CI) for the percentage difference between and ratio of proportions of cases and population.

This simulation was done for each racial/ethnic group within each county. The lower

bound of the CI was used to identify counties with disparities (as defined by percentage

differences or ratio). The mean of the estimated differences and mean of the estimated

ratios were calculated for all counties with disparities. Analyses were conducted

using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute).

During June 5–18, a total of 205 counties in 33 states were identified as hotspots.

These counties have a combined total population of 93.5 million persons, and approximately

535,000 cumulative probable and confirmed COVID-19 cases. Among the 205 identified

hotspot counties, 79 (38.5%) counties in 22 states, with a combined population of

27.5 million persons and approximately 162,000 COVID-19 cases, had race data available

for ≥50% of cumulative cases and were included in the analysis (range = 51.3%–97.4%).

Disparities in cases were identified among underrepresented racial/ethnic groups in

76 (96.2%) analyzed counties (Table 1). Disparities among Hispanic populations were

identified in approximately three quarters of hotspot counties (59 of 79, 74.7%) with

approximately 3.5 million Hispanic residents (Table 2). Approximately 2.0 million

black persons reside in 22 (27.8%) hotspot counties where black residents were disproportionately

affected by COVID-19, approximately 61,000 AI/AN persons live in three (3.8%) hotspot

counties where AI/AN residents were disproportionately affected by COVID-19, nearly

36,000 Asian persons live in four (5.1%) hotspot counties where Asian residents were

disproportionately affected by COVID-19, and approximately 31,000 NHPI persons live

in 19 (24.1%) hotspot counties where NHPI populations were disproportionately affected

by COVID-19.

TABLE 1

Total population and racial/ethnic disparities* in cumulative COVID-19 cases among

79 counties identified as hotspots during June 5–18, 2020, with any disparity identified

— 22 states, February–June 2020

State

No. of persons living in analyzed hotspot counties*

No. of (col %) hotspot counties analyzed†

No. of counties with disparities in COVID-19 cases among each racial/ethnic group§

Hispanic

Black

NHPI

Asian

AI/AN

Alabama

500,000–1,000,000

1 (1.3)

—

1

—

—

—

Arizona

1,000,000–3,000,000

5 (6.3)

3

—

—

—

3

Arkansas

500,000–1,000,000

4 (5.1)

4

—

2

—

—

California

1,000,000–3,000,000

1 (1.3)

1

—

—

—

—

Colorado

100,000–500,000

1 (1.3)

1

—

1

—

—

Florida

>3,000,000

6 (7.6)

3

2

—

—

—

Georgia

100,000–500,000

1 (1.3)

1

—

—

—

—

Iowa

50,000–100,000

1 (1.3)

1

—

—

—

—

Kansas

500,000–1,000,000

2 (2.5)

2

—

2

—

—

Massachusetts

500,000–1,000,000

2 (2.5)

—

2

—

—

—

Michigan

1,000,000–3,000,000

5 (6.3)

—

5

1

—

—

Minnesota

<50,000

1 (1.3)

1

1

1

1

—

Mississippi

100,000–500,000

2 (2.5)

1

2

—

—

—

North Carolina

>3,000,000

18 (22.8)

18

—

3

1

—

Ohio

1,000,000–3,000,000

3 (3.8)

3

2

—

1

—

Oregon

1,000,000–3,000,000

6 (7.6)

6

1

4

1

—

South Carolina

1,000,000–3,000,000

9 (11.4)

6

4

2

—

—

Tennessee

500,000–1,000,000

3 (3.8)

3

—

—

—

—

Texas

500,000–1,000,000

2 (2.5)

—

1

—

—

—

Utah

1,000,000–3,000,000

4 (5.1)

4

1

3

—

—

Virginia

<50,000

1 (1.3)

—

—

—

—

—

Wisconsin

100,000–500,000

1 (1.3)

1

—

—

—

—

Total (approximate)

27,500,000

79 (100)

59

22

19

4

3

Abbreviations: AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease

2019; NHPI = Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islanders.

* Disparities were defined as percentage difference of ≥5% between the proportion

of cases and the proportion of the population or a ratio ≥1.5 for the proportion of

cases to the proportion of the population) for underrepresented racial/ethnic groups

in each county.

† Counties with race/ethnicity data available for ≥50% of cases.

§ Racial/ethnic groups are not mutually exclusive in a given county.

TABLE 2

Number of persons in each racial/ethnic group living in 79 counties identified as

hotspots during June 5–18, 2020 with disparities* — 22 states, February–June 2020

Racial/Ethnic group

No. (%)† of counties with disparities§ identified

Approximate no. of persons living in hotspot counties with disparities

Hispanic/Latino

59 (74.7)

3,500,000

Black/African American

22 (27.8)

2,000,000

American Indian/Alaska Native

3 (3.8)

61,000

Asian

4 (5.1)

36,000

Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander

19 (24.1)

31,000

Total

—

5,628,000

Abbreviation: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

* Disparities were defined as percentage difference of ≥5% between the proportion

of cases and the proportion of the population or a ratio ≥1.5 for the proportion of

cases to the proportion of the population) for underrepresented racial/ethnic groups

in each county.

†

Percentage of the 79 counties.

§ Disparities are in respective racial/ethnic groups and are not mutually exclusive;

some counties had disparities in more than one racial/ethnic group.

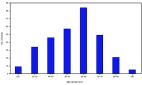

The mean of the estimated differences between the proportion of cases and proportion

of the population consisting of each underrepresented racial/ethnic group in all counties

with disparities ranged from 4.5% (NHPI) to 39.3% (AI/AN) (Table 3). The mean of the

estimated ratio of the proportion of cases to the proportions of population were also

generated for each underrepresented racial/ethnic group and ranged from 2.3 (black)

to 8.5 (NHPI).

TABLE 3

Proportion of cumulative COVID-19 cases compared with proportion of population in

79 counties identified as hotspots during June 5–18, 2020 with racial/ethnic disparities*

— 22 states February–June 2020

Racial/Ethnic group

Mean of estimated differences, † % (range)

Mean of estimated ratios of proportion of cases to proportion of population§ (range)

Hispanic/Latino

30.2 (8.0–68.2)

4.4 (1.2–14.6)

Black/African American

14.5 (2.3–31.7)

2.3 (1.2–7.0)

American Indian/Alaska Native

39.3 (16.4–57.9)

4.2 (1.9–6.4)

Asian

4.7 (2.7–6.8)

2.9 (2.0–4.7)

Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander

4.5 (0.1–31.5)

8.5 (2.7–18.4)

Abbreviation: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

* Disparities were defined as percentage

difference of ≥5% between the proportion of cases and the proportion of the population

or a ratio ≥1.5 for the proportion of cases to the proportion of the population) for

underrepresented racial/ethnic groups in each county.

† The mean of the estimated differences between the proportion of cases in a given

racial/ethnic group and the proportion of persons in that racial/ethnic group in the

overall population among all counties with disparities identified by the analysis.

For example, if Hispanic/Latino persons make up 20% of the population in a given county

and 30% of the cases in that county, then the difference would be 10% and the county

is considered to have a disparity.

§ The ratio of the estimated proportion of cases to the proportion of population for

each racial/ethnic group among all counties with disparities identified by the analysis.

For example, if American Indian/Alaskan Native persons made up 0.5% of the population

in a given county and 1.5% of the cases in that county, then the ratio of proportions

would be 3.0, and the county is considered to have a disparity.

Discussion

These findings illustrate the disproportionate incidence of COVID-19 among communities

of color, as has been shown by other studies, and suggest that a high percentage of

cases in hotspot counties are among persons of color (

1

–

5

,

7

). Among all underrepresented racial/ethnic groups in these hotspot counties, Hispanic

persons were the largest group living in hotspot counties with a disparity in cases

identified within that population (3.5 million persons). This finding is consistent

with other evidence highlighting the disproportionate incidence of COVID-19 among

the Hispanic population (

2

,

7

). The disproportionate incidence of COVID-19 among black populations is well documented

(

1

–

3

). The findings from this analysis align with other data indicating that black persons

are overrepresented among COVID-19 cases, associated hospitalizations, and deaths

in the United States. The analysis found few counties with disparities among AI/AN

populations. This finding is likely attributable to the smaller proportions of cases

and populations of AI/AN identified in hotspot counties, as well as challenges with

data for this group, including a lack of surveillance data and misclassification problems

in large data sets.

¶

Asian populations were disproportionately affected by COVID-19 in a small number of

hotspot counties. Few studies have assessed COVID-19 disparities among Asian populations

in the United States.** The Asian racial category is broad, and further subgroup analyses

might provide additional insights regarding the incidence of COVID-19 in this population.

Disparities in COVID-19 cases in NHPI populations were identified in nearly one quarter

of hotspot counties. For some hotspot counties with small NHPI populations, this finding

might be related, in part, to the analytic methodology used. Using a ratio of ≥1.5

in the proportion of population and proportion of cases to indicate disparities is

sensitive to small differences in these groups. More complete county-level race/ethnicity

data are needed to fully evaluate the disproportionate incidence of COVID-19 among

communities of color.

Disparities in COVID-19–associated mortality in hotspot counties were not assessed

because the available county-level mortality data disaggregated by race/ethnicity

were not sufficient to generate reliable estimates. Existing national analyses highlight

disparities in mortality associated with COVID-19; similar patterns are likely to

exist at the county level (

5

). As more complete data are made available in the future, county-level analyses examining

disparities in mortality might be possible. COVID-19 disparities among underrepresented

racial/ethnic groups likely result from a multitude of conditions that lead to increased

risk for exposure to SARS-CoV-2, including structural factors, such as economic and

housing policies and the built environment,

††

and social factors such as essential worker employment status requiring in-person

work (e.g., meatpacking, agriculture, service, and health care), residence in multigenerational

and multifamily households, and overrepresentation in congregate living environments

with an increased risk for transmission (

4

,

7

–

9

). Further, long-standing discrimination and social inequities might contribute to

factors that increase risk for severe disease and death, such as limited access to

health care, underlying medical conditions, and higher levels of exposure to pollution

and environmental hazards

§§

(

4

). The conditions contributing to disparities likely vary widely within and among

groups, depending on location and other contextual factors.

Rates of SARS-CoV-2 transmission vary by region and time, resulting in nonuniform

disease outbreak patterns across the United States. Therefore, using epidemiologic

indicators to identify hotspot counties currently affected by SARS-CoV-2 transmission

can inform a data-driven emergency response. Tailoring strategies to control SARS-CoV-2

transmission could reduce the overall incidence of COVID-19 in communities. Using

these data to identify disproportionately affected groups at the county level can

guide the allocation of resources, development of culturally and linguistically tailored

prevention activities, and implementation of focused testing efforts.

The findings in this report are subject to at least five limitations. First, more

than half of the hotspot counties did not report sufficient race data and were therefore

excluded from the analysis. In addition, many hotspot counties included in the analyses

were missing data on race for a significant proportion of cases (mean = 28.3%; range

= 2.6%–48.7%). These data gaps might result from jurisdictions having to reconcile

data from multiple sources for a large volume of cases while data collection and management

processes are rapidly evolving.

¶¶

Second, health departments differ in the way race/ethnicity are reported, making comparisons

across counties and states more difficult. Third, differences in how race/ethnicity

data are collected (e.g., self-report versus observation) likely varies by setting

and could lead to miscategorization. Fourth, differences in access to COVID-19 testing

could lead to underestimates of prevalence in some underrepresented racial/ethnic

populations. Finally, the number of cases that had available race/ethnicity data for

the period of study of hotspots (June 5–18) was too small to generate reliable estimates,

so cumulative case counts by county during February–June 2020 were used to identify

disparities. This approach describes the racial/ethnic breakdown of cumulative cases

only. Therefore, these data might not provide an accurate estimate of disparities

during June 5–18, which could be under- or overestimated, or change over time.

Developing culturally responsive, targeted interventions in partnership with trusted

leaders and community-based organizations within communities of color might reduce

disparities in COVID-19 incidence. Increasing the proportion of cases for which race/ethnicity

data are collected and reported can help inform efforts in the short-term to better

understand patterns of incidence and mortality. Existing health inequities amplified

by COVID-19 highlight the need for continued investment in communities of color to

address social determinants of health*** and structural racism that affect health

beyond this pandemic (

4

,

8

). Long-term efforts should focus on addressing societal factors that contribute to

broader health disparities across communities of color.

Summary

What is already known about this topic?

Long-standing health and social inequities have resulted in increased risk for infection,

severe illness, and death from COVID-19 among communities of color.

What is added by this report?

Among 79 counties identified as hotspots during June 5–18, 2020 that also had sufficient

data on race, a disproportionate number of COVID-19 cases among underrepresented racial/ethnic

groups occurred in almost all areas during February–June 2020.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Identifying health disparities in COVID-19 hotspot counties can inform testing and

prevention efforts. Addressing the pandemic’s disproportionate incidence among communities

of color can improve community-wide health outcomes related to COVID-19.

Related collections

Most cited references6

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Coronavirus Disease 2019 Case Surveillance — United States, January 22–May 30, 2020

Erin K. Stokes, Laura Zambrano, Kayla N. Anderson … (2020)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes of Adult Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19 — Georgia, March 2020

Jeremy Gold, Karen Wong, Christine Szablewski … (2020)

- Record: found

- Abstract: found

- Article: found

Characteristics Associated with Hospitalization Among Patients with COVID-19 — Metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia, March–April 2020

Marie Killerby, Ruth Link-Gelles, Sarah Haight … (2020)